Art for the Masses

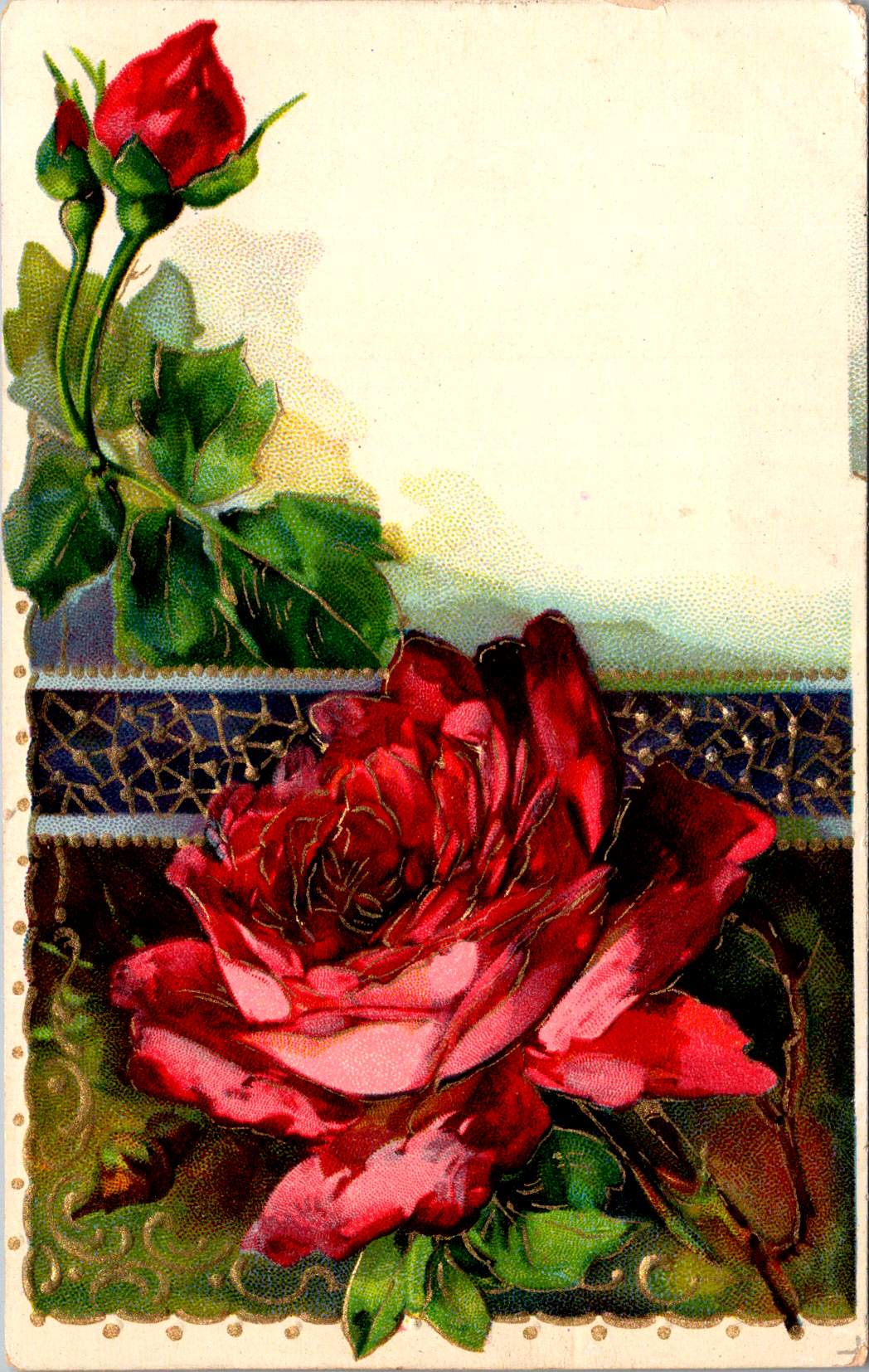

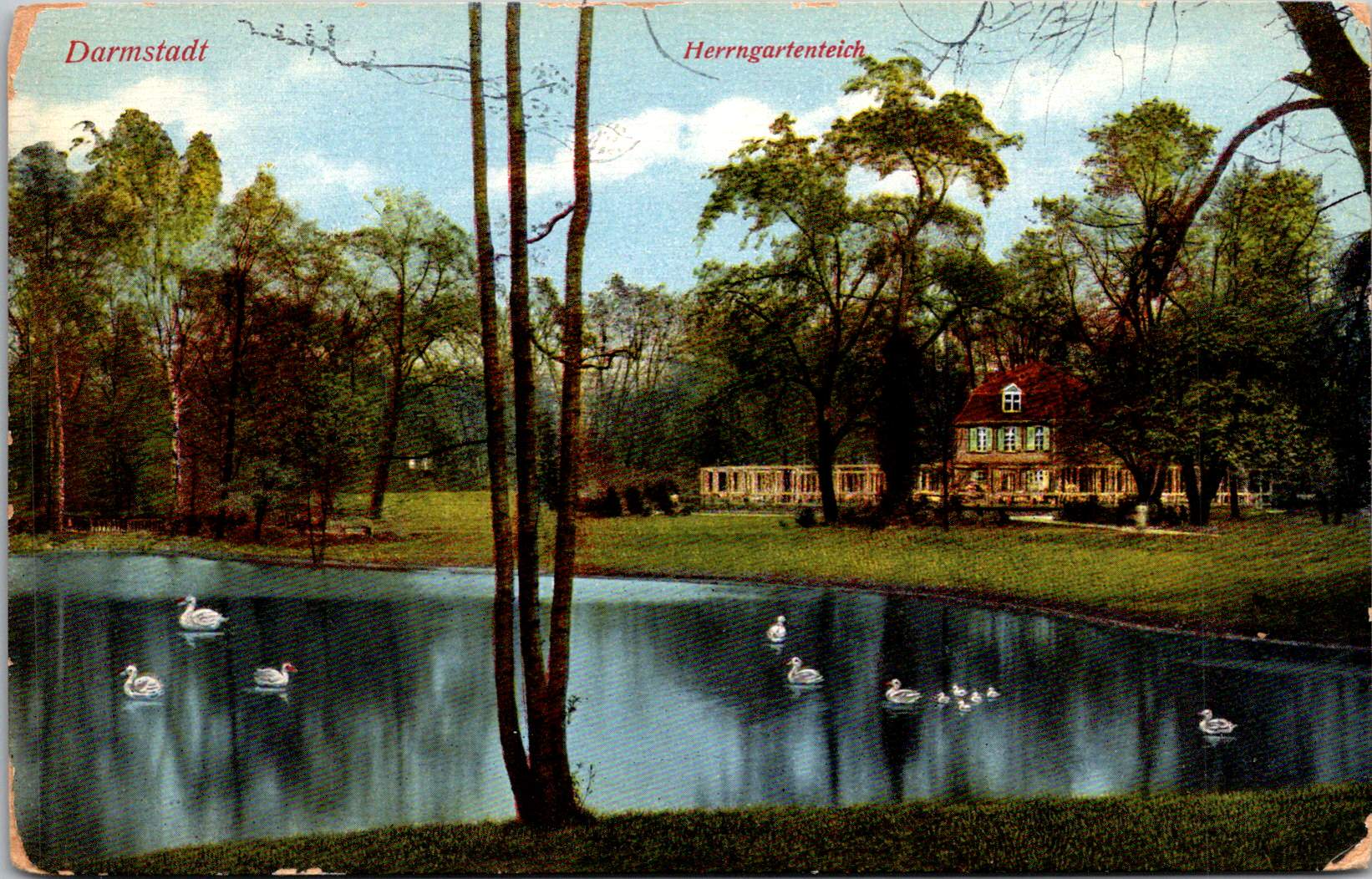

The development of chromolithography in the late 19th century provided the technological foundation for colorful mass-produced postcards. Though lithography itself dated back to 1796, when Alois Senefelder developed the process in Munich, the refinement of color lithography reached new heights in the 1870s-90s, with different national styles emerging.

German printers particularly mastered the technique of creating separate limestone printing plates for each color, allowing for vibrant multi-color images that previously would have required expensive hand-coloring. A typical color postcard might require five to fifteen separate printing runs, with perfect registration between colors. This level of precision required specialized equipment and highly trained craftsmen.

German chemical industries produced superior inks and dyes, giving their postcards more vibrant and stable colors than competitors. Companies like BASF and Bayer, originally founded as dye manufacturers, provided innovative colorants specifically formulated for printing applications.

The German city of Leipzig emerged as a center of printing excellence, with firms like Meissner & Buch establishing international reputations for quality. German chromolithography was so superior that even American publishers would often have their designs sent to Germany for printing, then shipped back to the United States for distribution—at least until tariff changes in 1909 made this practice less economical. Publishers like Raphael Tuck & Sons maintained offices in Germany despite being headquartered in London, simply to access German printing expertise.

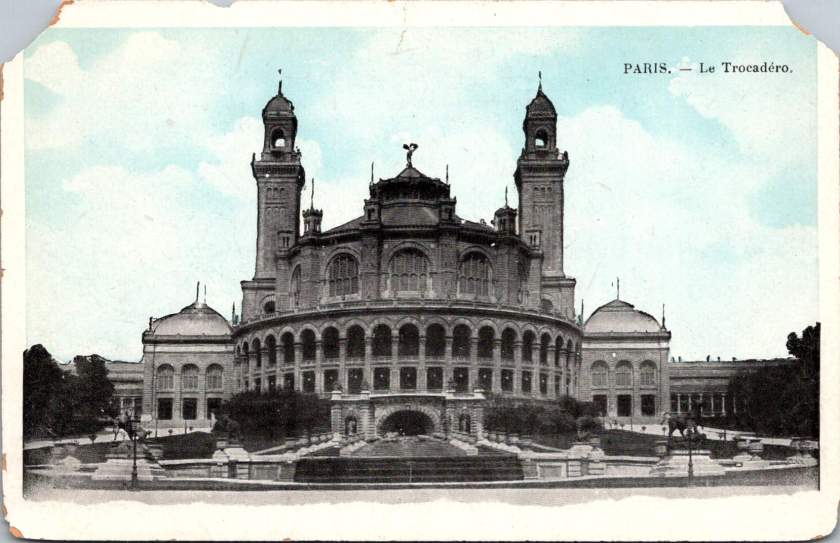

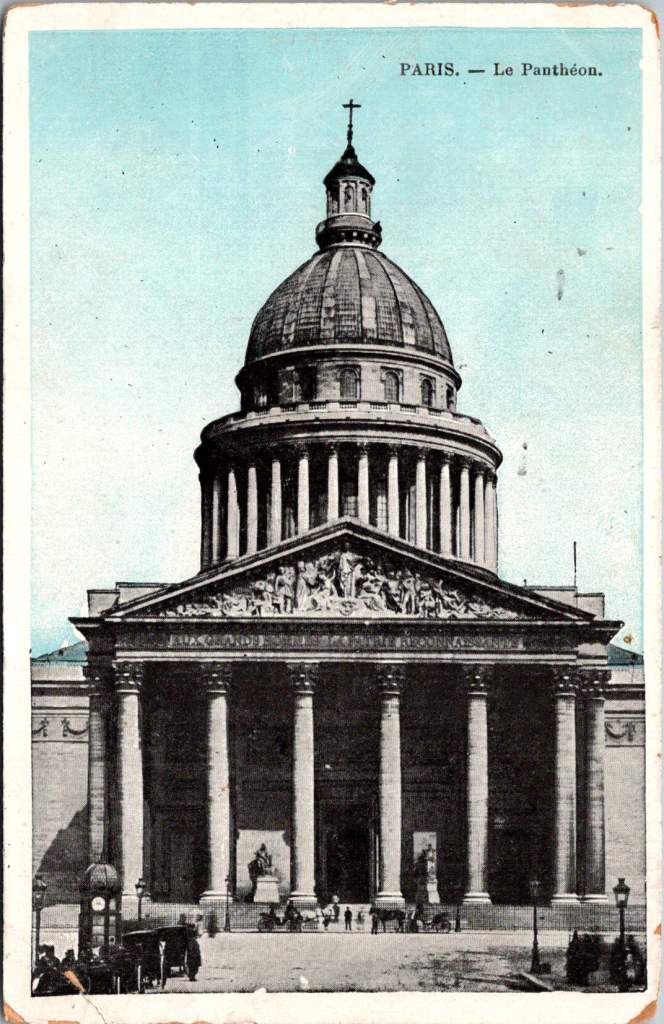

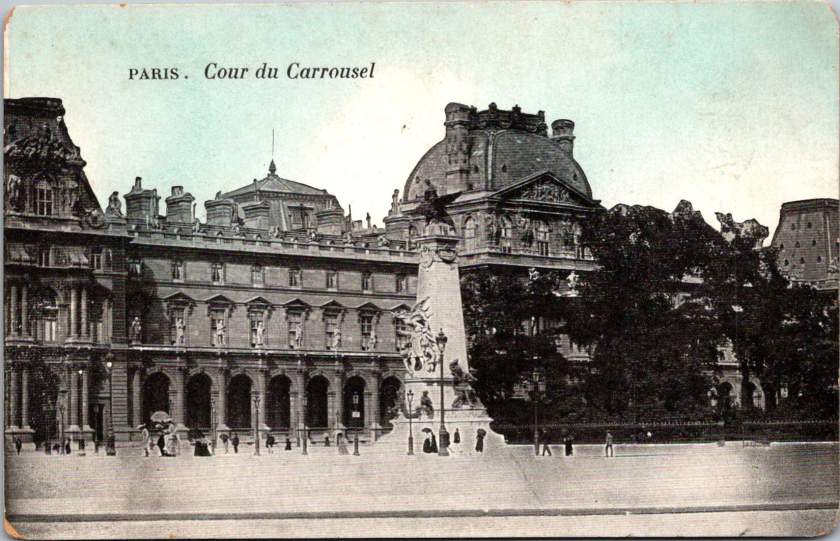

While Germany led in technical quality, French postcards developed a reputation for artistic sophistication. Paris publishers like Bergeret and Levy et Fils produced cards featuring Art Nouveau styles and artistic photographic techniques. The French market also developed distinctive “Fantaisie” postcards featuring elaborate designs with silk applications, mechanical elements, or attached novelties. These cards pushed the boundaries of what a postcard could be, turning functional communication into miniature works of art.

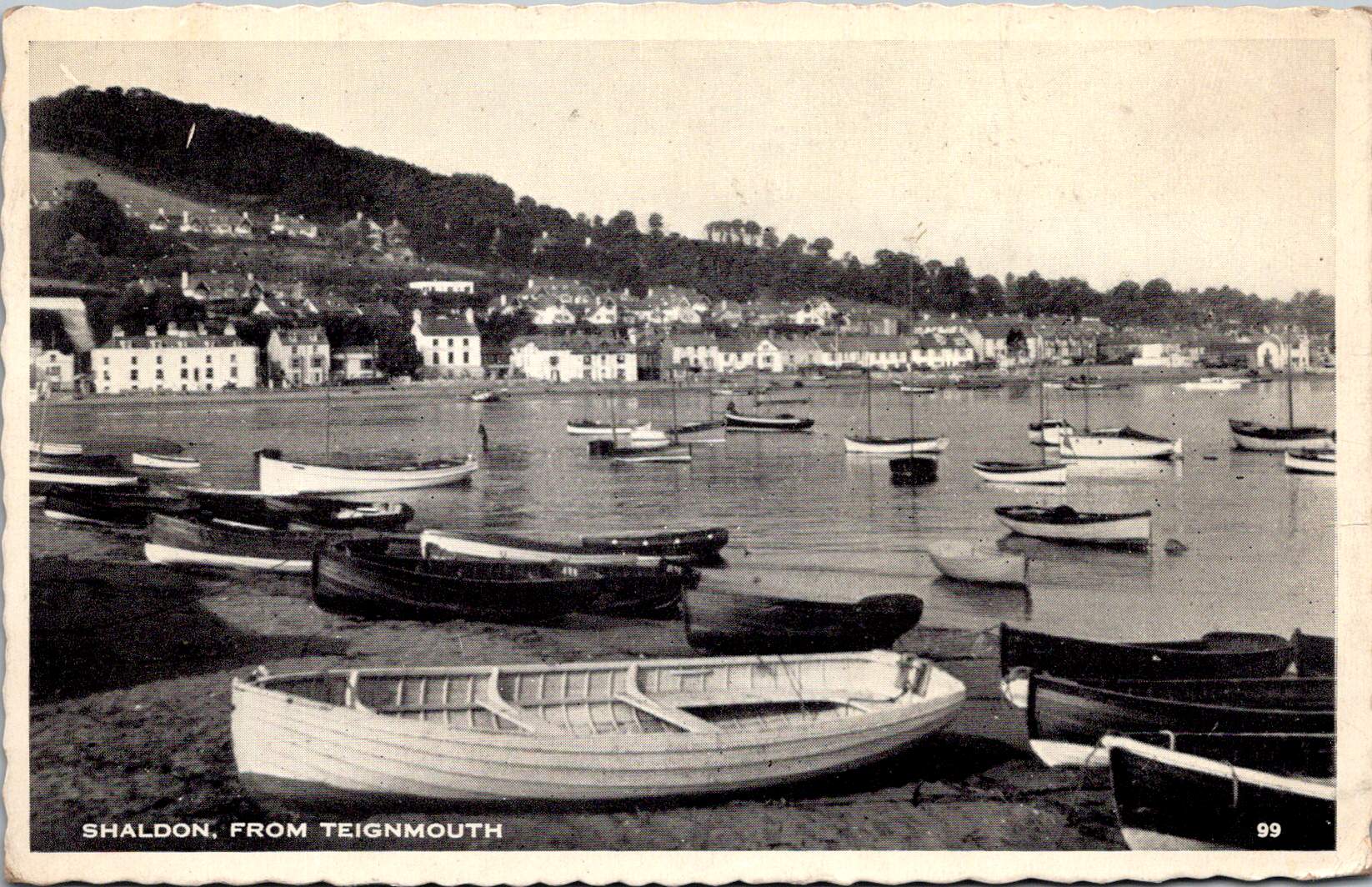

British publishers like Raphael Tuck & Sons, J. Valentine & Co., and Bamforth & Co. showed particular commercial acumen. While they didn’t match German printing quality or French artistic sensibility, British firms excelled at identifying market opportunities and consumer trends. The British pioneered specialized categories like the seaside postcard and led in developing postcards for specific holidays and occasions.

Photographic Reality

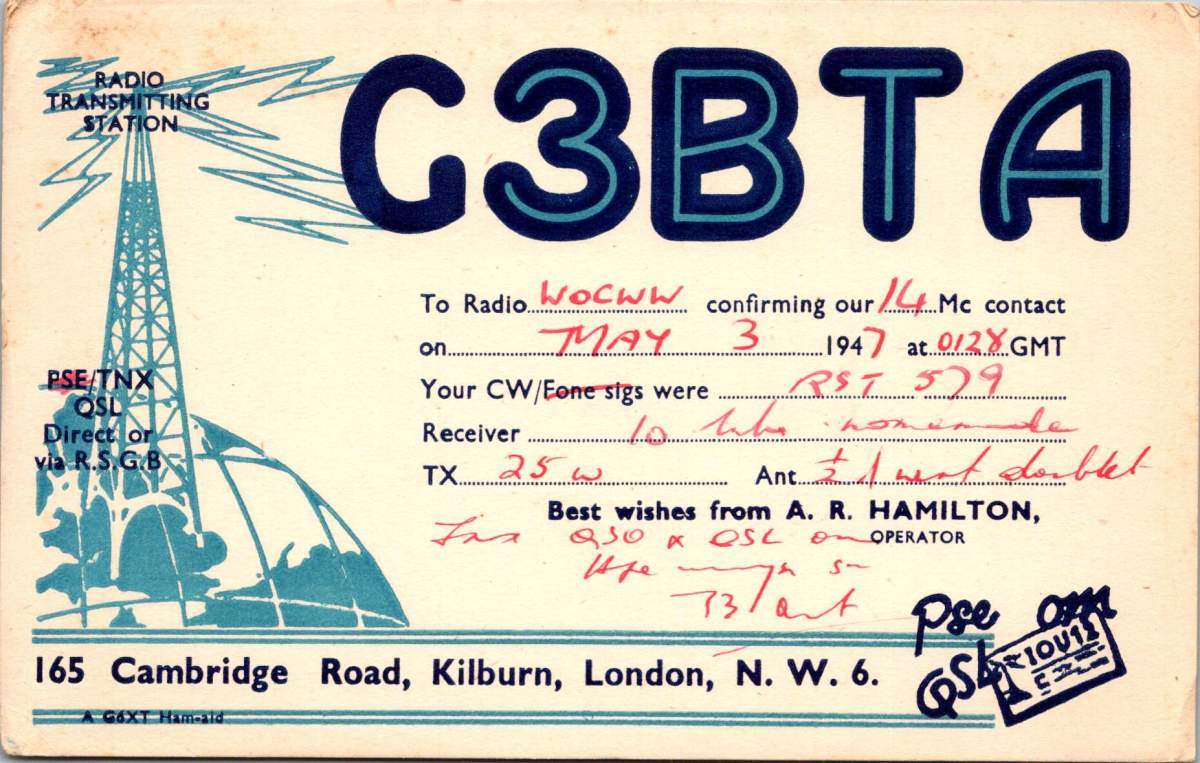

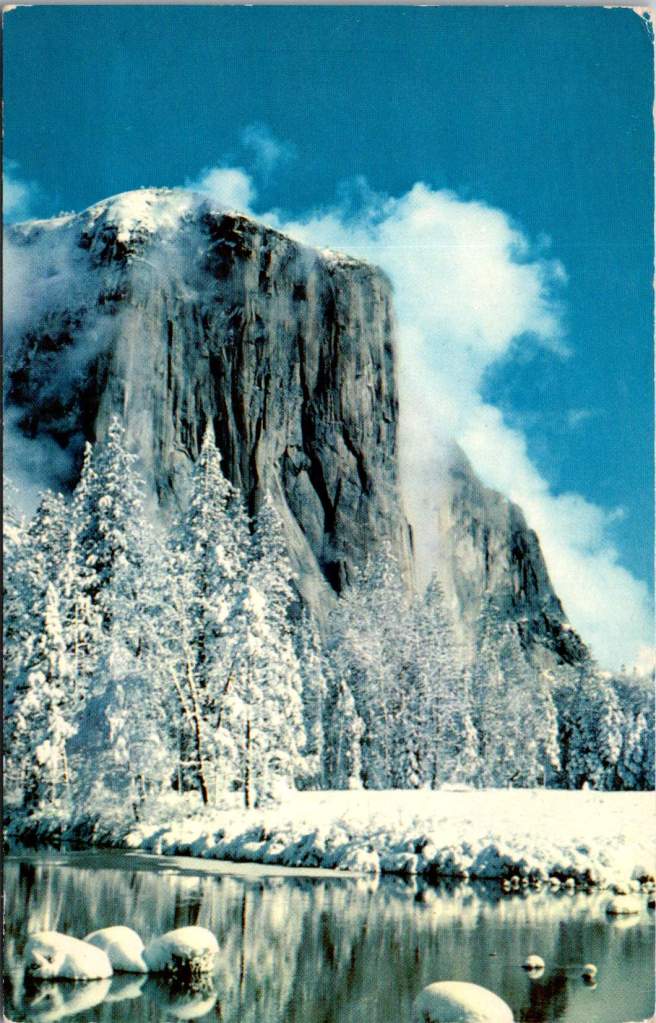

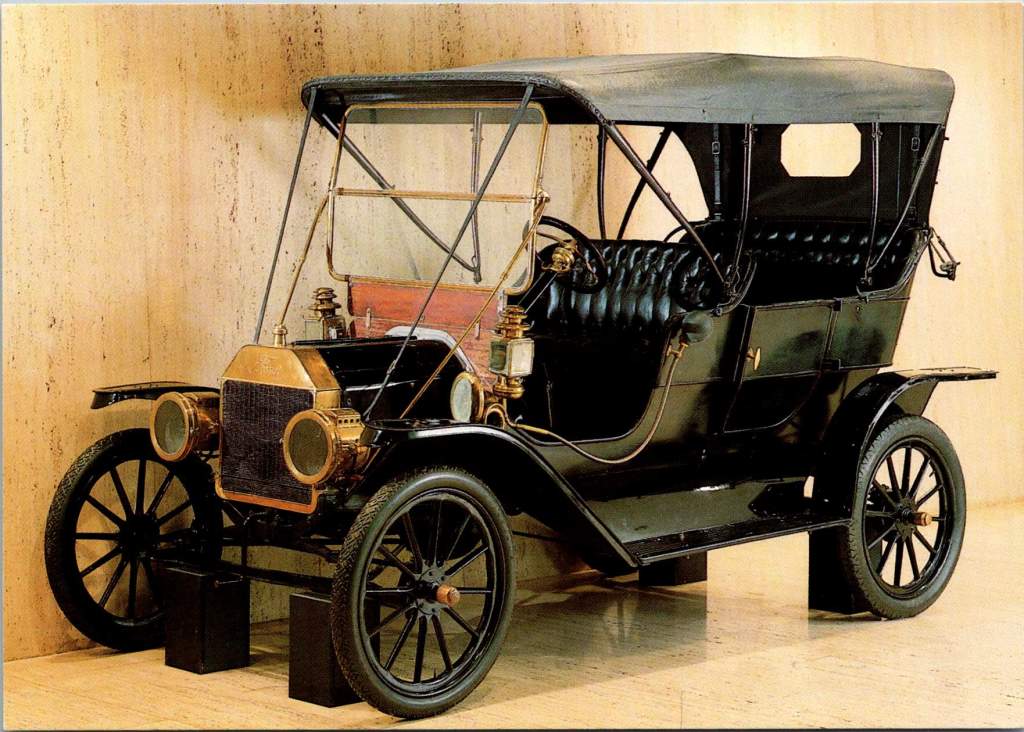

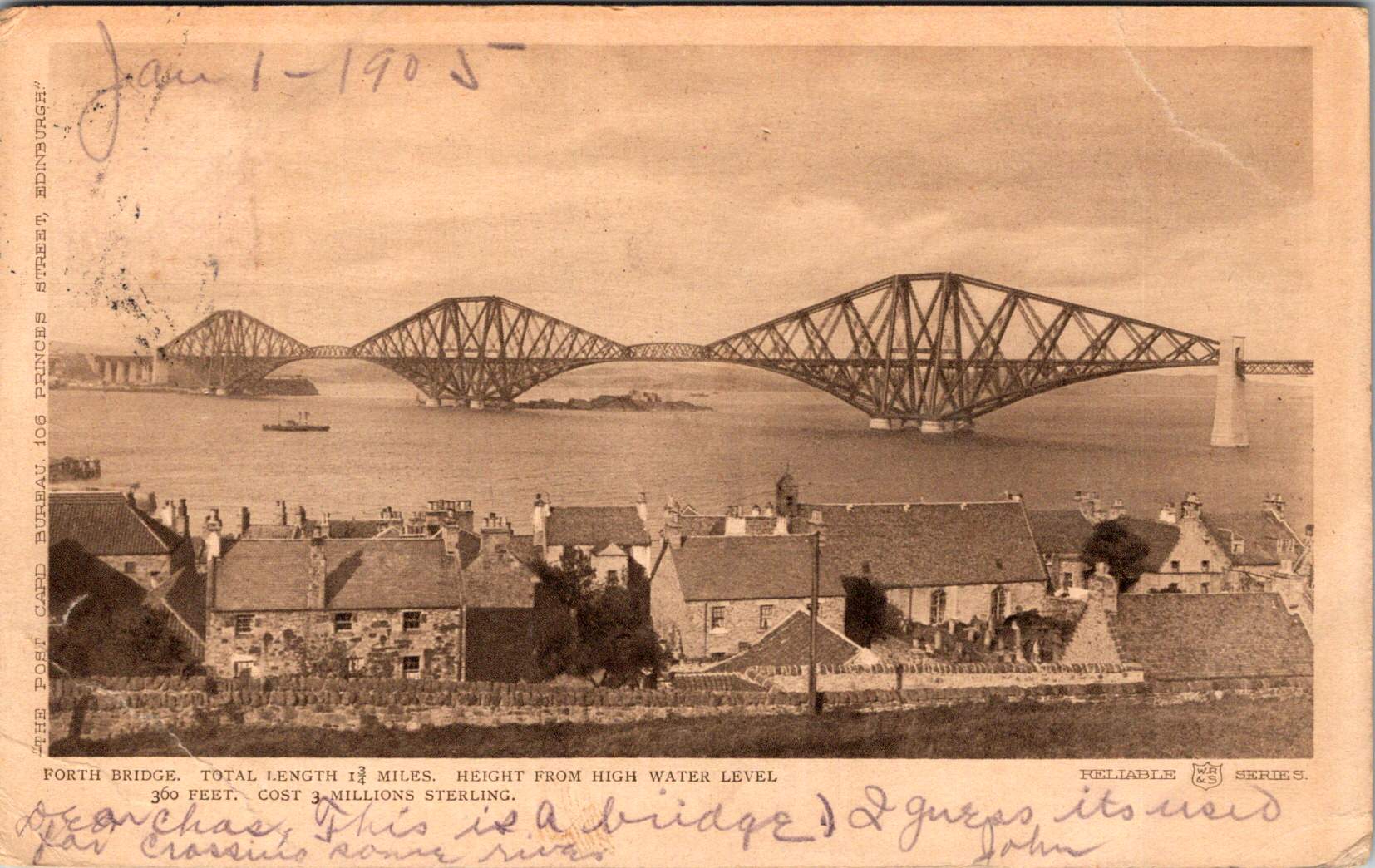

While lithographic postcards dominated the market, photography increasingly influenced postcard production. The collodion wet plate process (1851) and later the gelatin dry plate (1871) made photography more accessible. The development of halftone printing in the 1880s allowed photographs to be reproduced in print media without manual engraving, creating more realistic imagery.

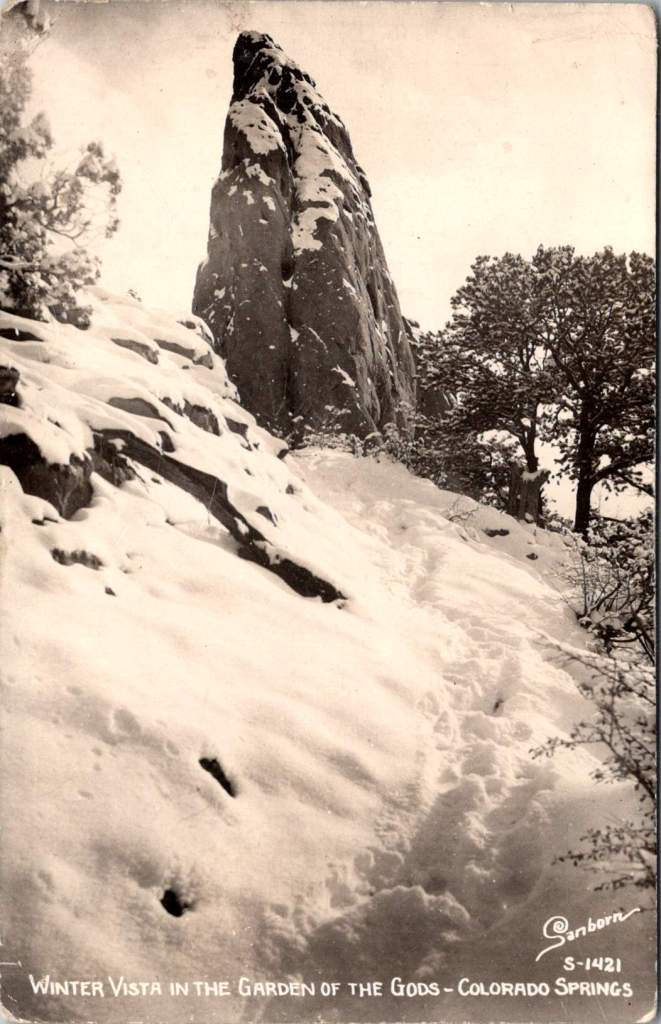

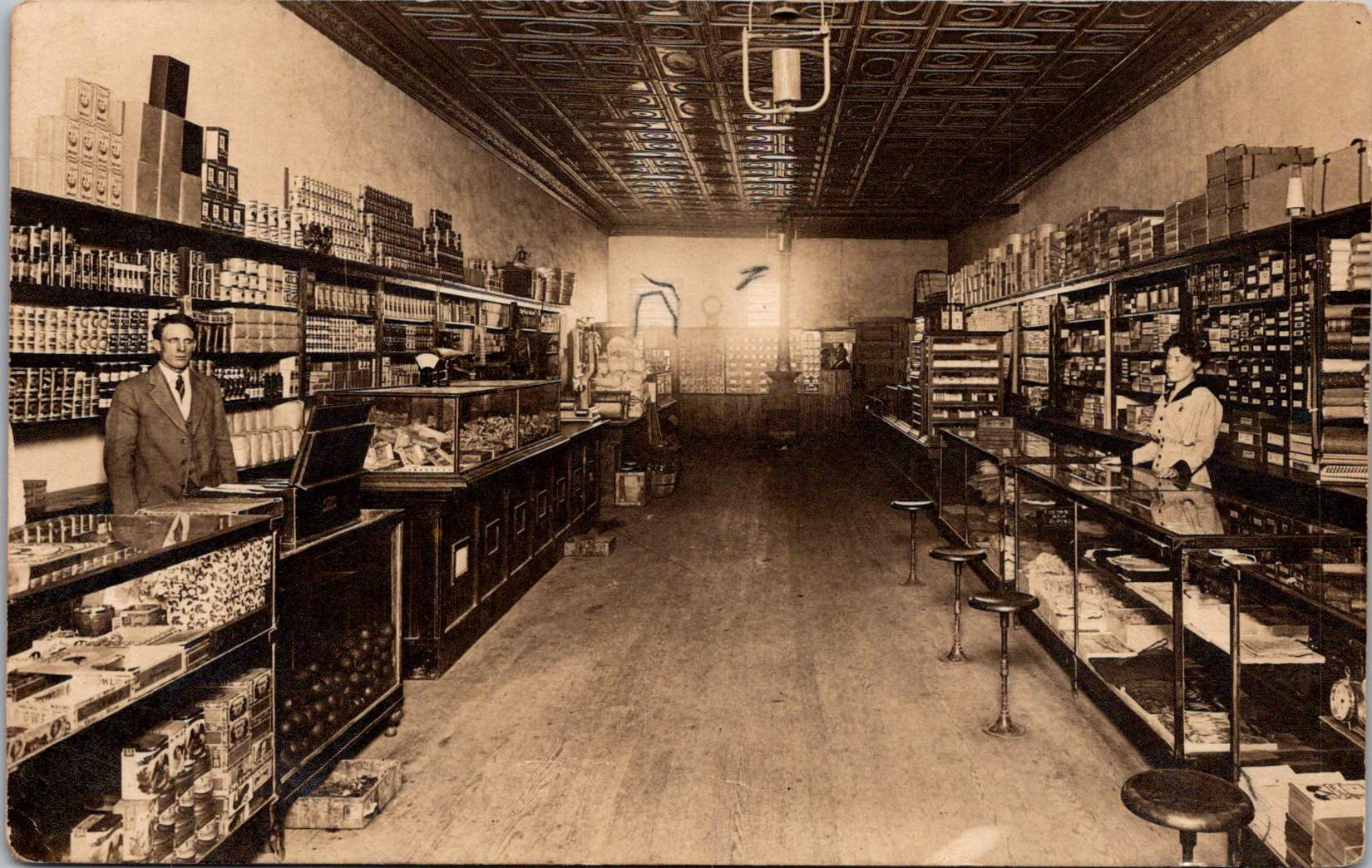

A revolutionary moment came in 1903 when Eastman Kodak introduced “Velox” postcard paper. This pre-printed photographic paper had postcard markings on the back and a light-sensitive photo emulsion on the front. Combined with Kodak’s 3A Folding Pocket camera, which produced negatives exactly postcard size (3¼ × 5½ inches), this innovation created the Real Photo Postcard (RPPC).

The acquisition of Leo Baekeland’s Velox photographic paper company in 1899 for $1 million provided a crucial technological component. Velox paper could be developed in artificial light rather than requiring darkroom conditions, had faster developing times, and produced rich blacks and clear whites—all critical qualities for postcard production.

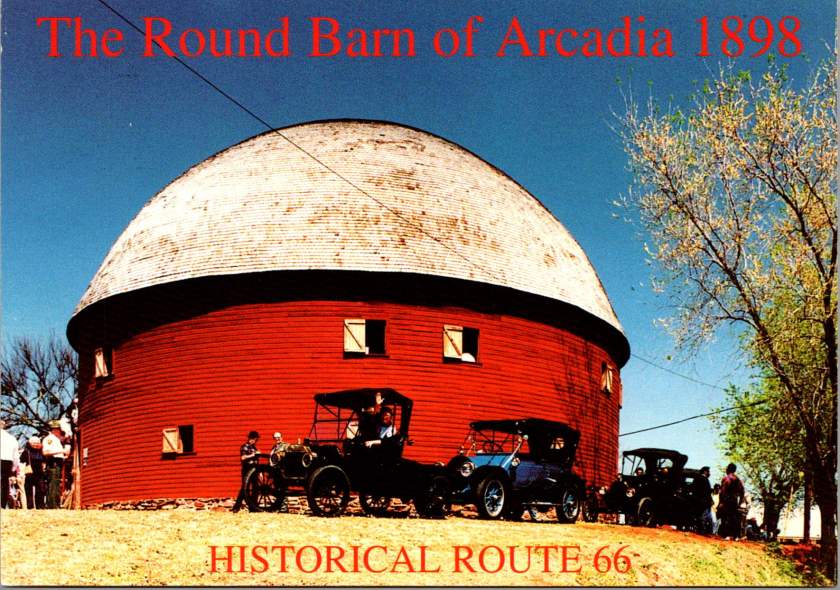

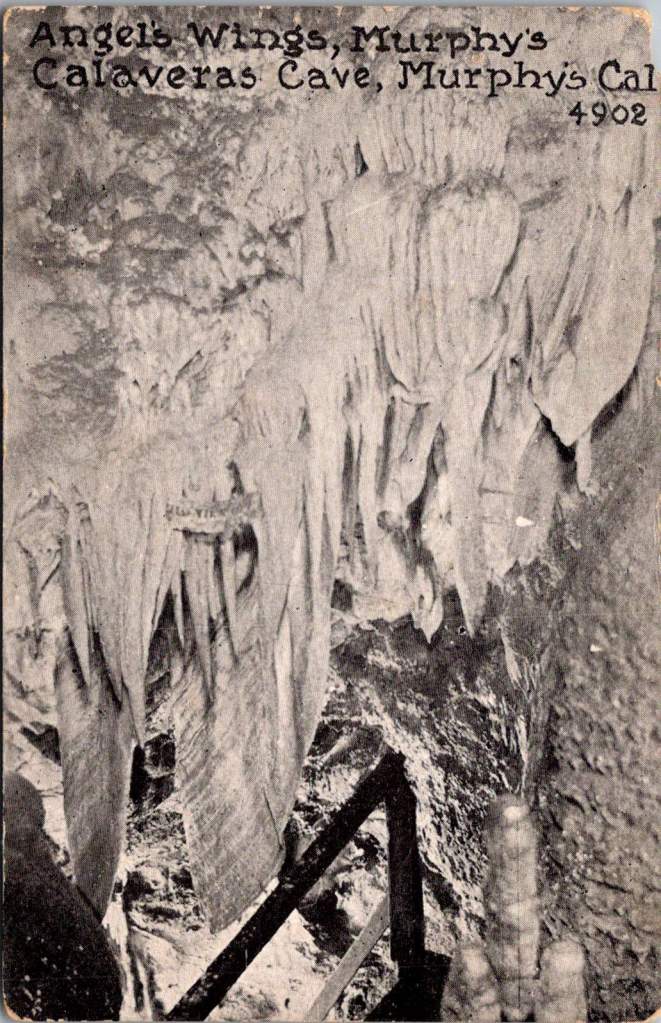

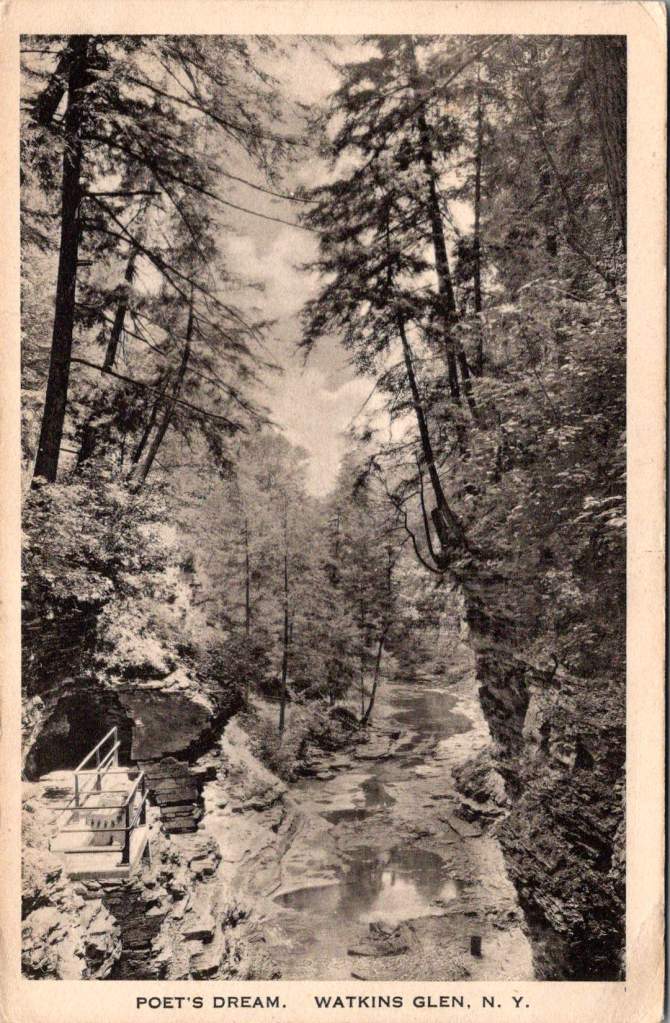

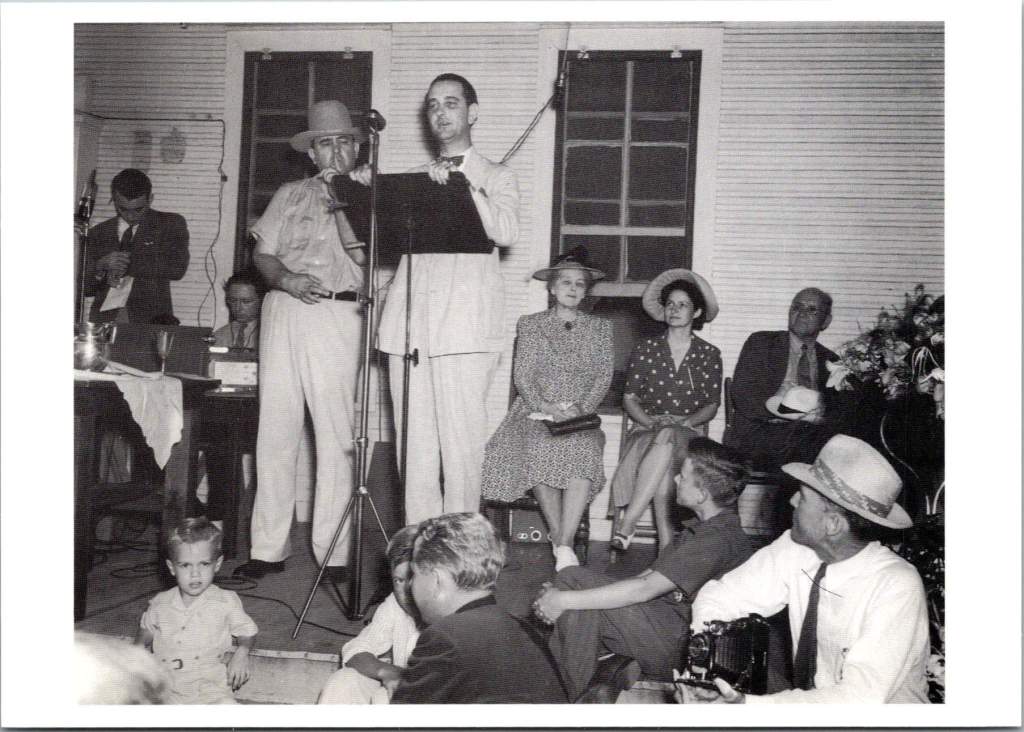

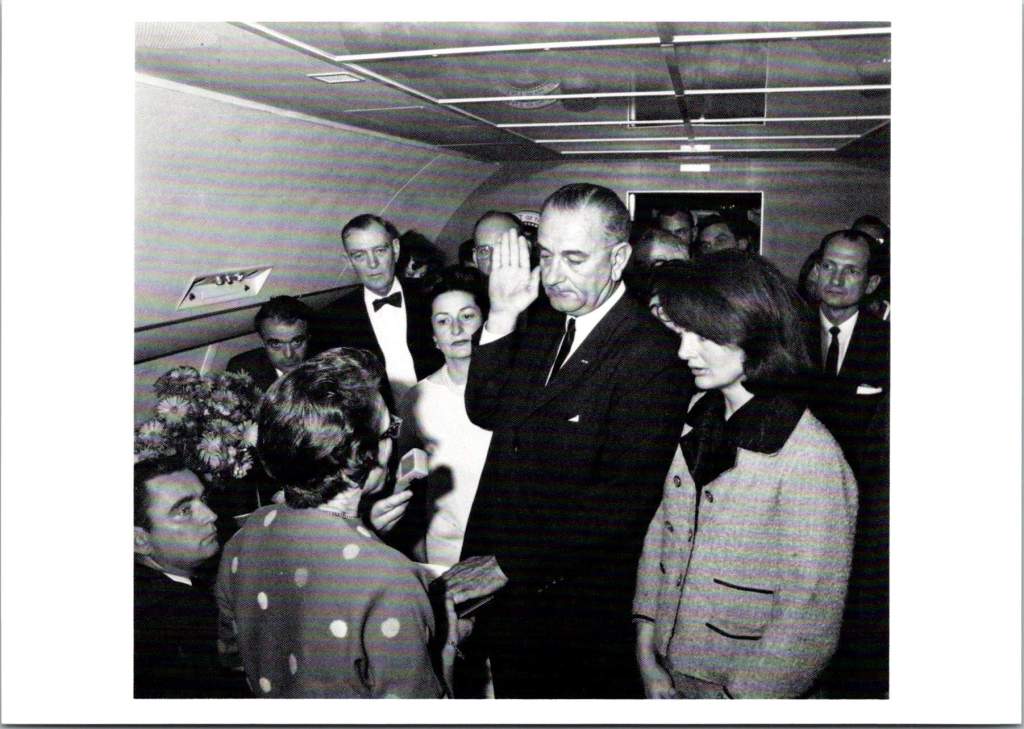

The RPPC format found particular success in America, where the vast geography meant many small towns would never appear on commercially printed postcards. Local photographers throughout the country created RPPCs of main streets, businesses, schools, and community events, documenting American life with unprecedented comprehensiveness.

International Postal Agreements

Even the most beautifully produced postcard would be meaningless without an efficient system to deliver it. The standardization of postal systems in the late 19th century created the infrastructure necessary for postcards to flourish.

A watershed moment for international mail came with the Treaty of Bern in 1874, establishing the General Postal Union (later renamed the Universal Postal Union or UPU). This organization created the first truly international postal agreement, initially signed by 22 countries, primarily European nations. The United States joined the UPU in July 1875, connecting the American postal system to the standardized European networks. The U.S. had introduced its own government-issued postal cards in 1873, but joining the UPU meant these could now be sent internationally under consistent regulations.

Several key UPU Congress developments shaped the postcard’s evolution. The 1878 Paris Congress renamed the organization to Universal Postal Union. The 1885 Lisbon Congress standardized the maximum size for postcards (9 × 14 cm). The 1897 Washington Congress set new international regulations for private postcards. The 1906 Rome Congress standardized the divided back format internationally.

Perhaps the most crucial postal development for postcard popularity was the divided back. Great Britain introduced this format in 1902, with France and Germany following in 1904, and the United States in 1907. Before the divided back, the entire reverse of a postcard was reserved for the address only, with messages having to be squeezed onto the front, often around the image. The new format allocated half the back for the address and half for a message, dramatically improving postcards’ utility as correspondence tools.

European Delivery Systems

European railway networks proved ideal for postal delivery, creating a remarkably efficient system. By the 1870s-80s, most European countries had developed comprehensive rail networks. Germany alone had over 24,000 miles of railway by 1895, despite having a land area smaller than Texas.

Railway mail cars (“bureaux ambulants” in France, “Bahnpost” in Germany) sorted mail en route. These mobile sorting offices made the system highly efficient, with mail sorted by destination while in transit. Railway timetables were coordinated to allow for mail transfers at junction points, creating an integrated system even across national borders.

Major routes often saw multiple mail trains per day. The Berlin-Cologne line, for example, had four daily postal services by 1900. This meant that postcards could be delivered between major cities within a day, creating a communication speed previously unimaginable.

For urban delivery, European cities developed even more innovative systems. Perhaps most remarkable were the pneumatic tube networks installed in several European capitals. Paris launched its “Pneumatique” in 1866, Vienna’s “Rohrpost” began in 1875, and Berlin built an extensive pneumatic network from 1865. These systems used compressed air pressure to propel cylindrical containers through networks of tubes. The carriers could hold several postcards or letters and traveled at speeds up to 35 kilometers per hour. Paris eventually developed a pneumatic tube network extending 467 kilometers, allowing for delivery times of under 30 minutes across the city. A morning postcard could receive an afternoon reply—creating a nearly conversational pace of written communication.

American Adaptations

The United States faced different geographical challenges. The vast distances between population centers meant that the same-day delivery common in Europe was impossible between major cities. Nevertheless, the American postal system developed impressive efficiency given these constraints.

The U.S. Railway Mail Service, officially established in 1869, became the backbone of American mail delivery. By 1900, more than 9,000 railway postal clerks were sorting mail on trains covering more than 175,000 miles of routes. While European countries measured mail routes in hundreds of miles, American routes stretched thousands of miles across the continent.

American cities also experimented with pneumatic tube systems, though they were less extensive than European counterparts. New York City’s system, operating from 1897 to 1953, eventually covered 27 miles with tubes connecting post offices in Manhattan and Brooklyn. At its peak, it transported 95,000 letters per day, or about 30% of all first-class mail in the city.

Within cities, frequent delivery became the norm. By 1900, many American urban areas offered at least four daily mail deliveries, with some business districts receiving up to seven deliveries per day. This made postcards a practical means of daily communication within city limits, much as they were in Europe.

The efficiency and economy of postcards made them ideal for routine business communications. Companies developed pre-printed postcards for order acknowledgments, shipping notifications, payment reminders, meeting confirmations, service calls, and appointment reminders. These standardized communications reduced clerical costs while providing a paper trail of business interactions. The divided back format was particularly valuable for business purposes, allowing for both a standardized message and customized details.

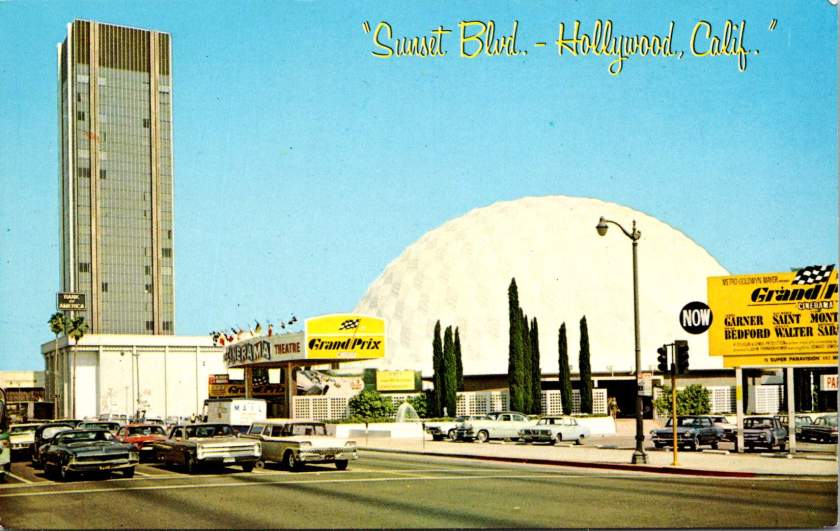

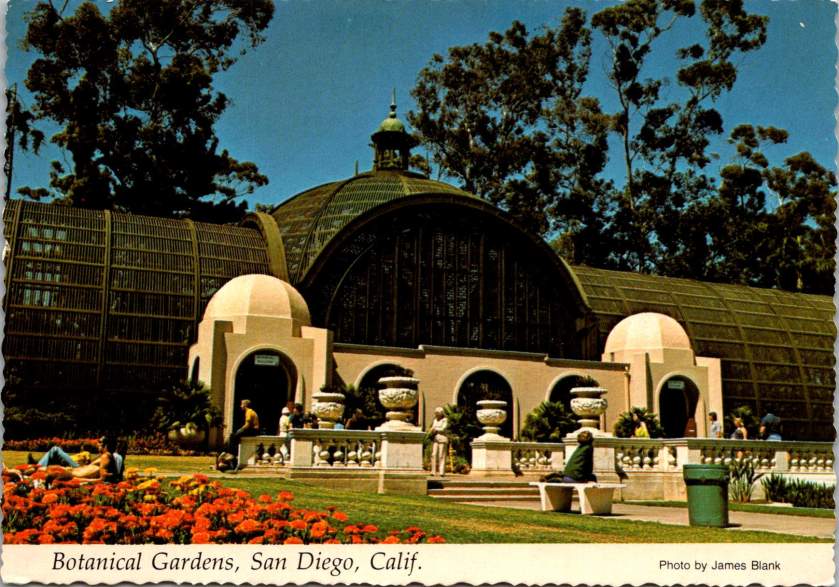

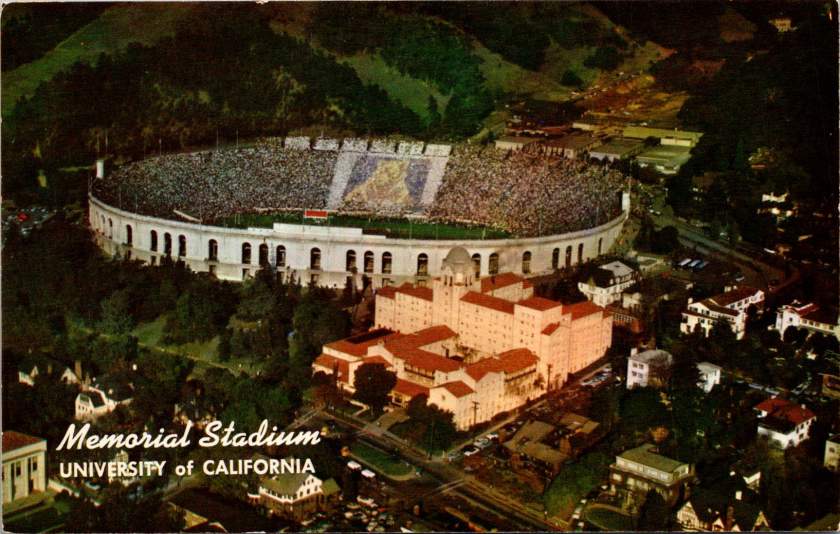

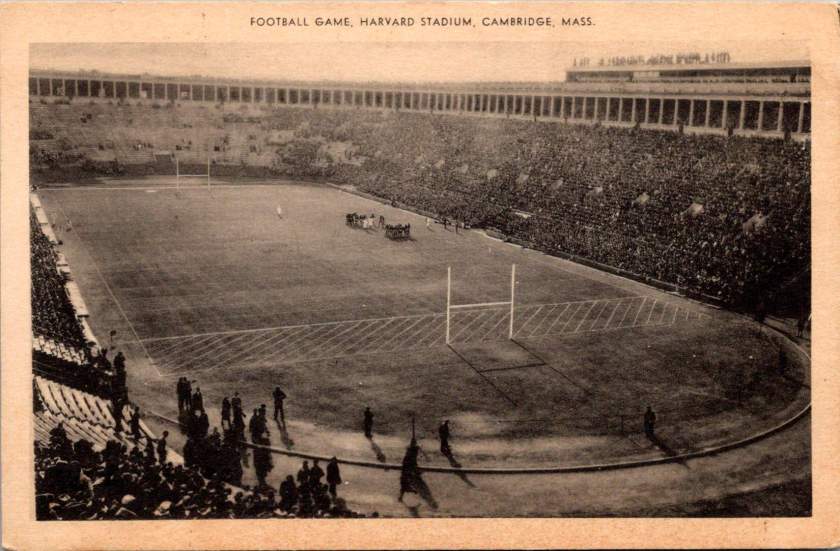

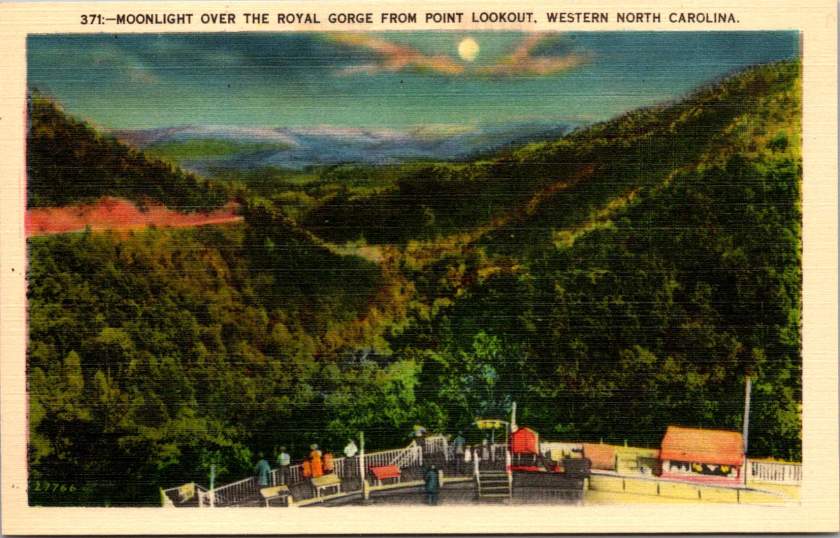

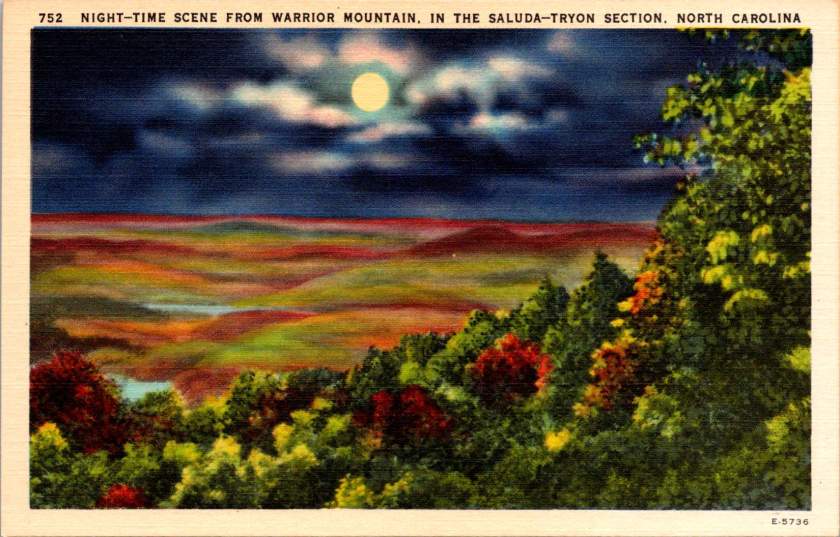

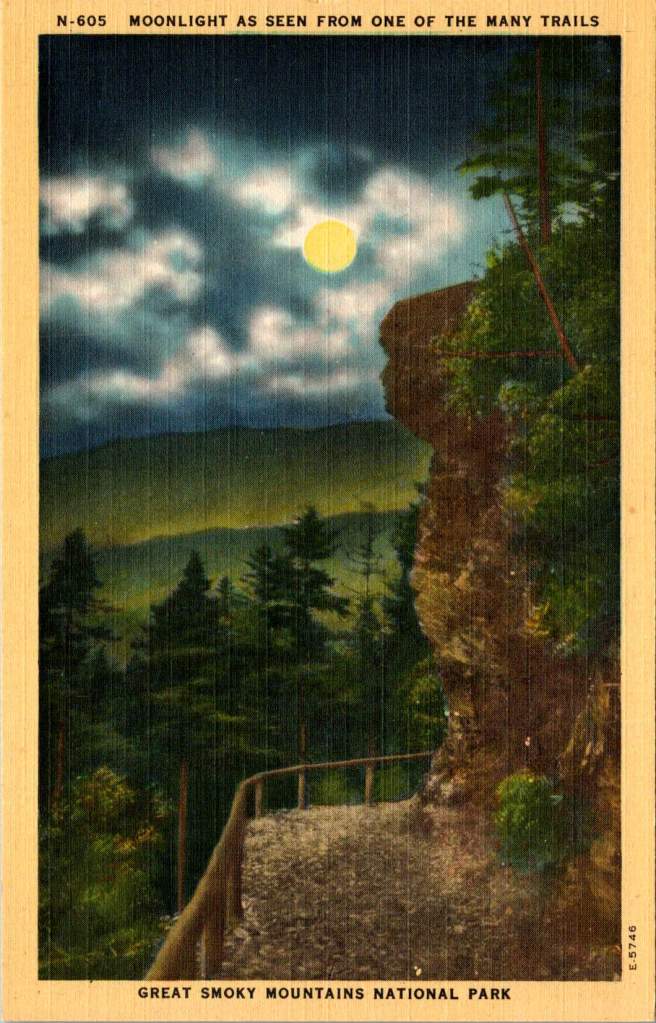

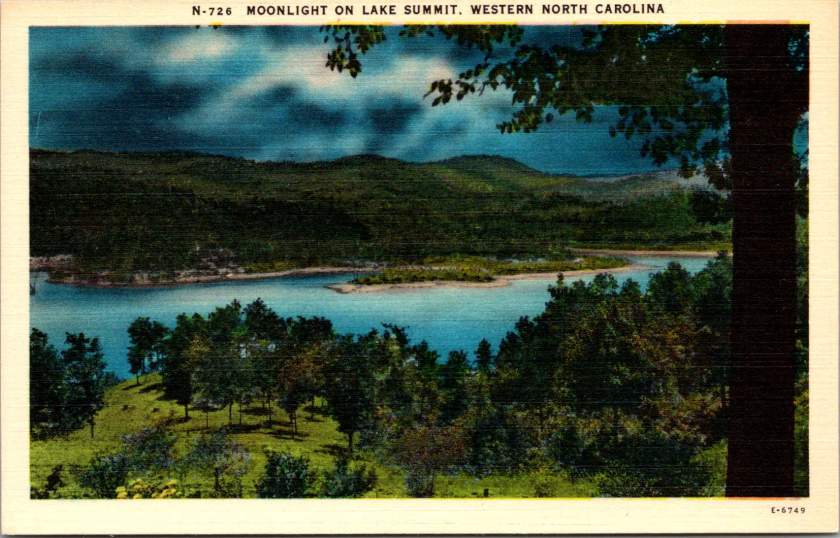

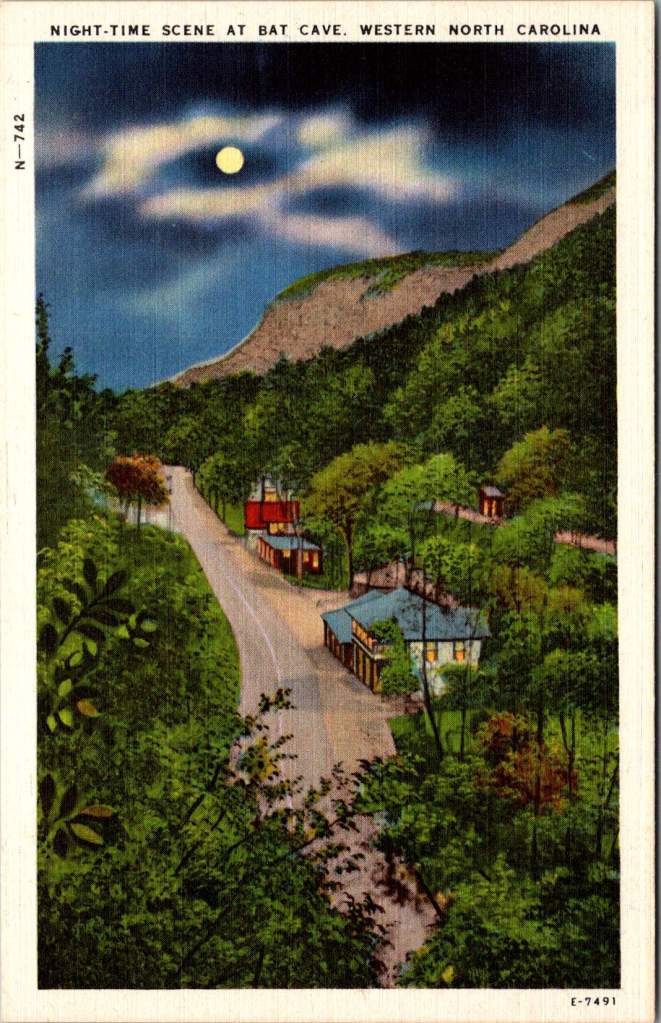

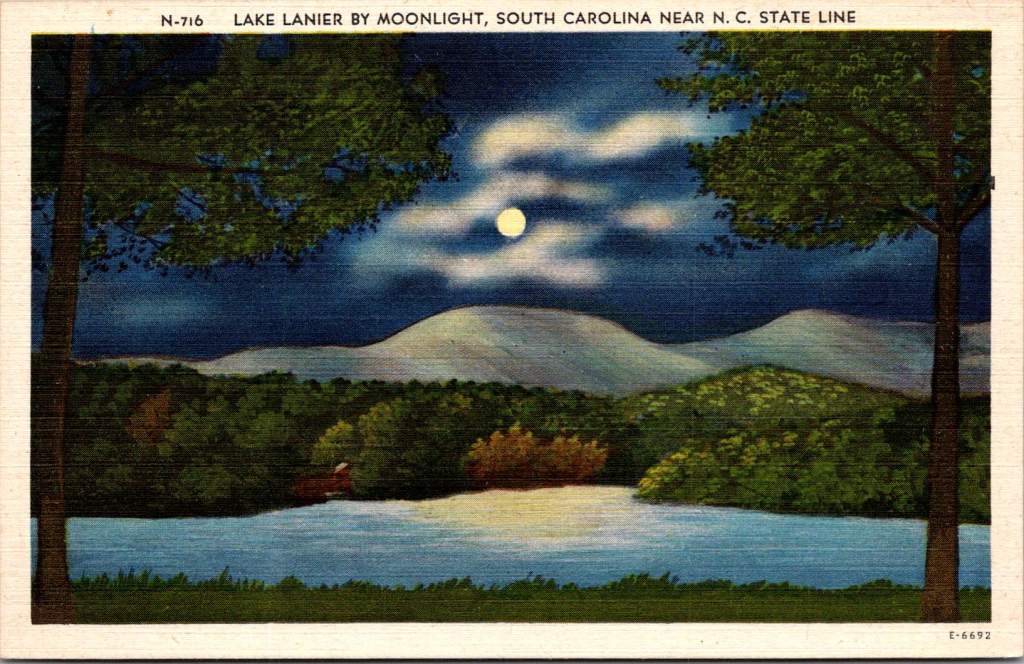

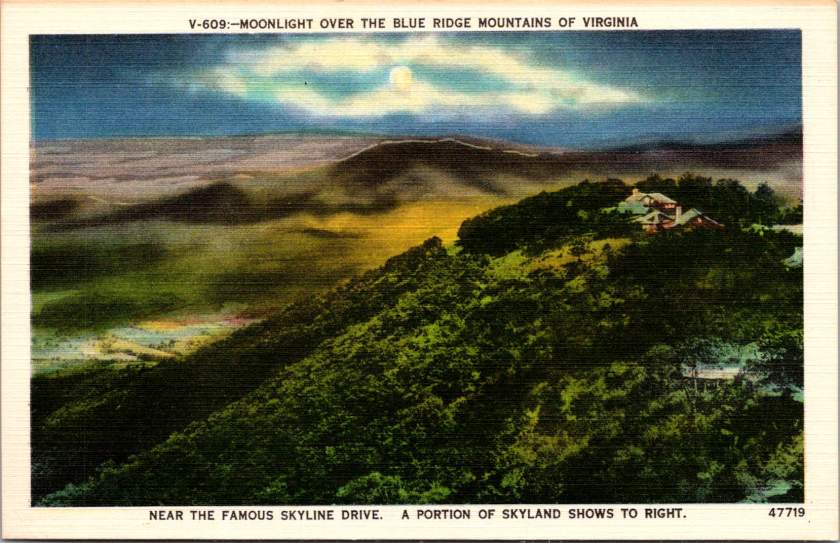

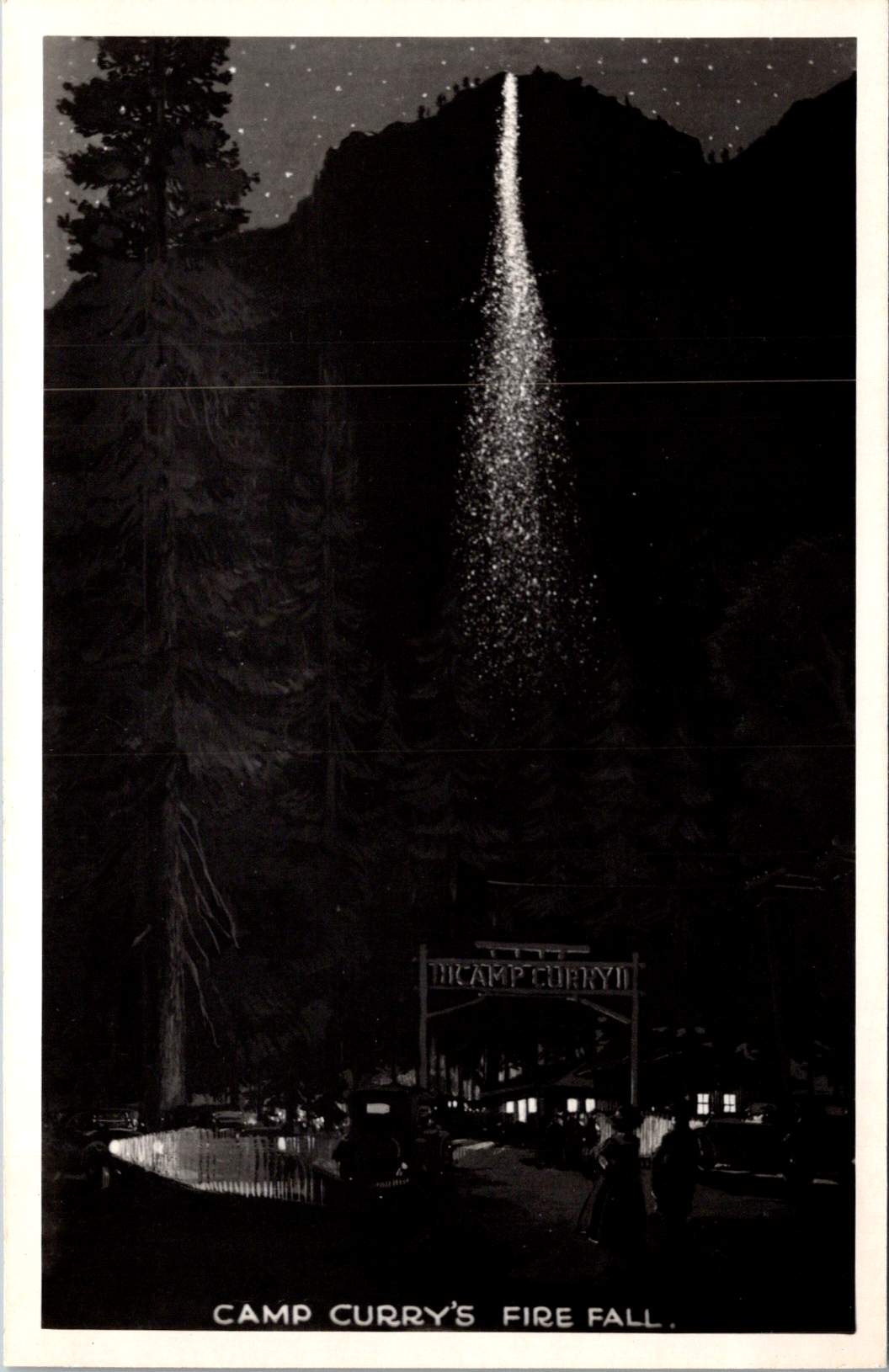

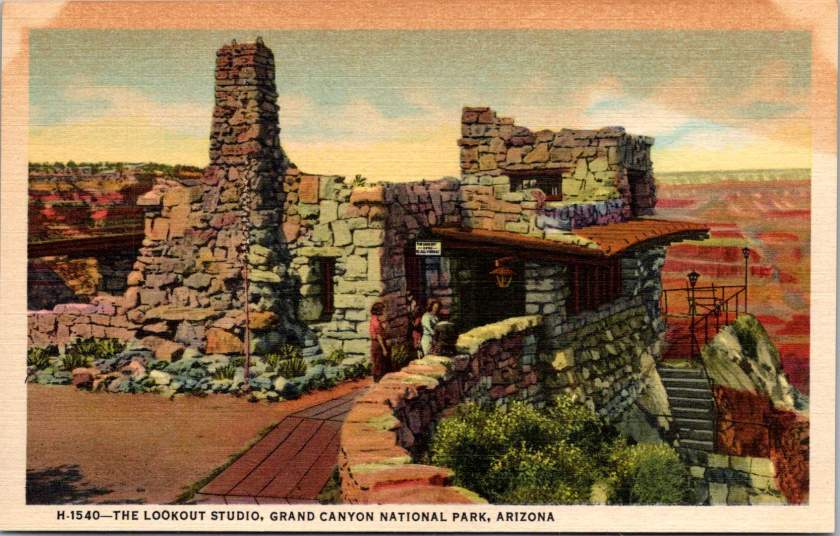

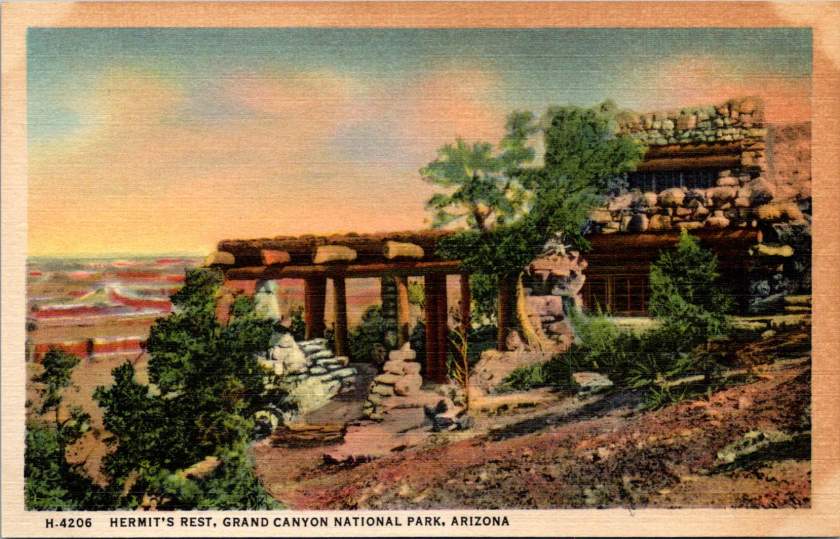

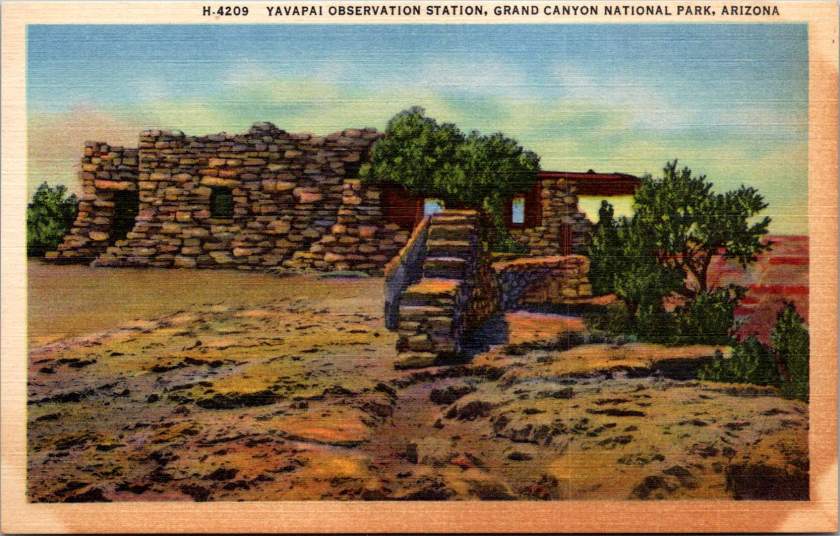

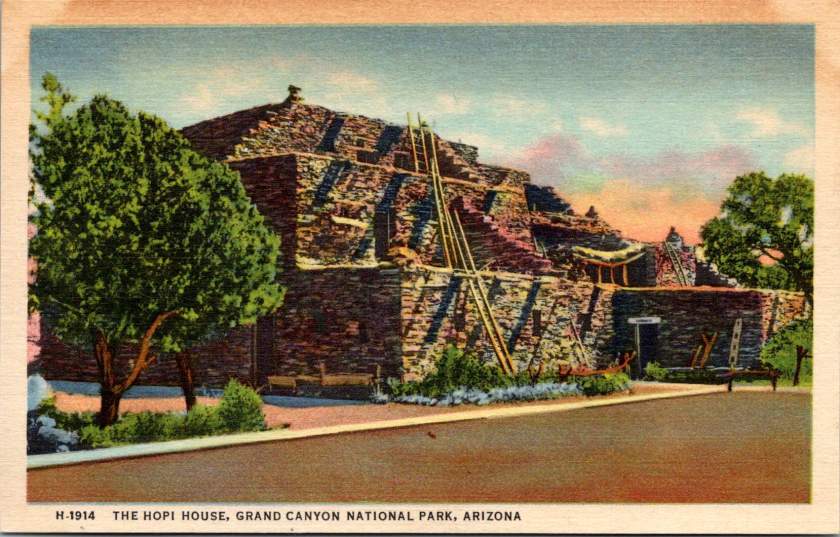

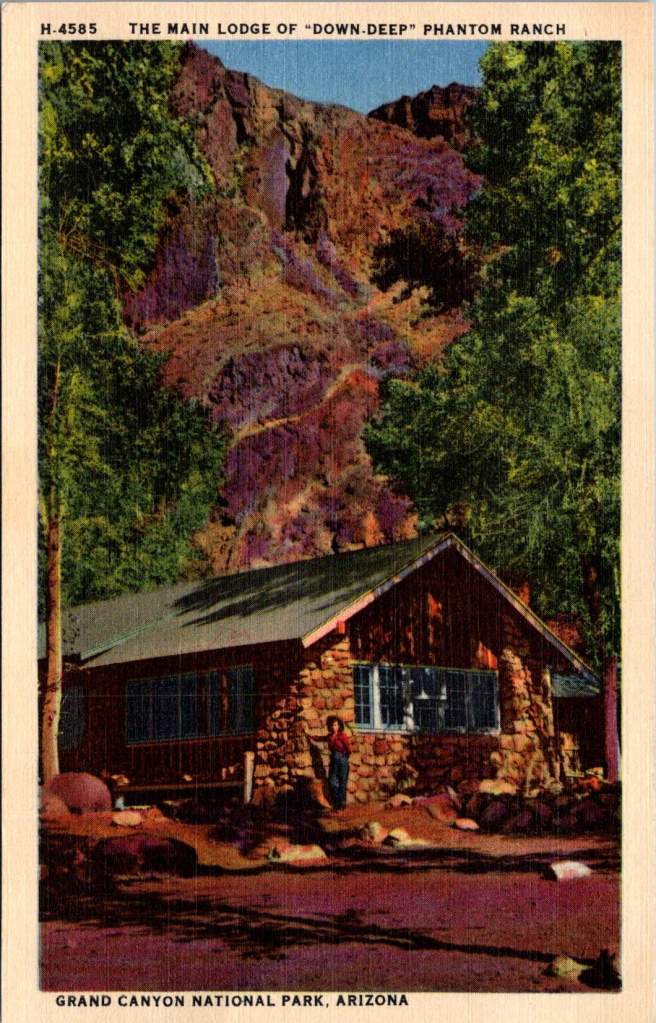

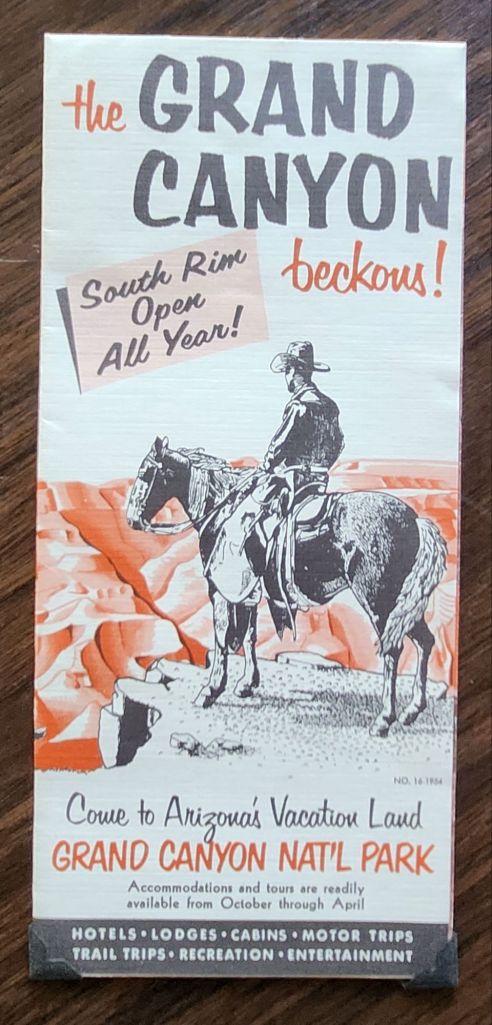

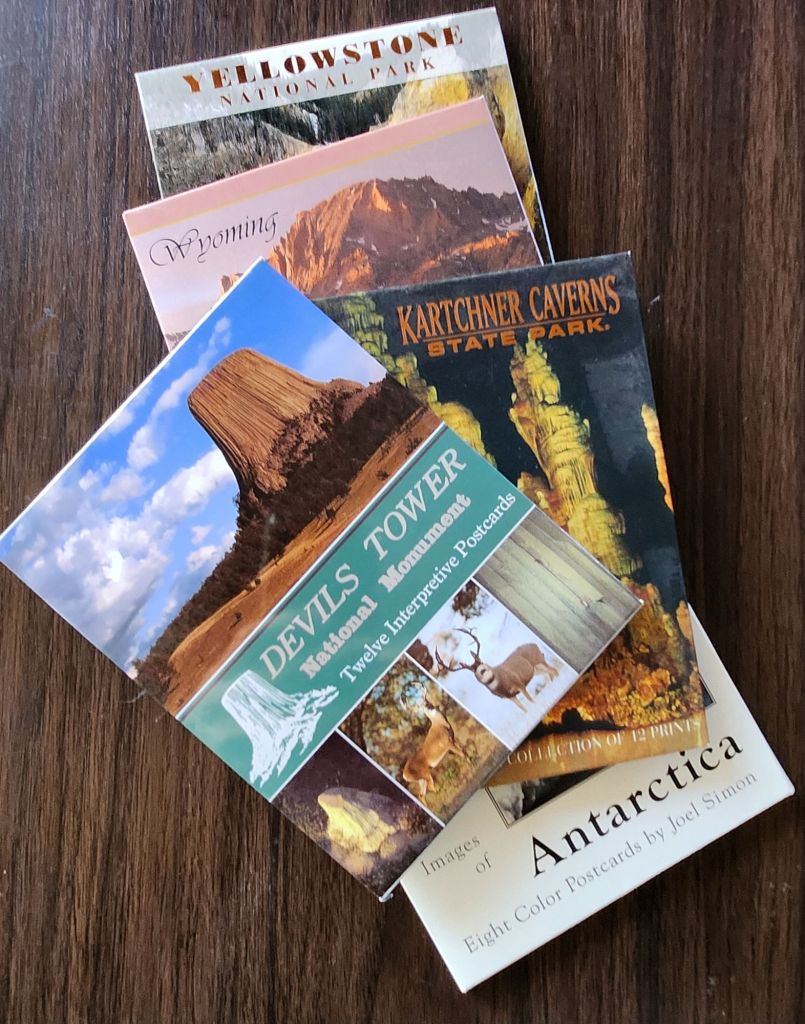

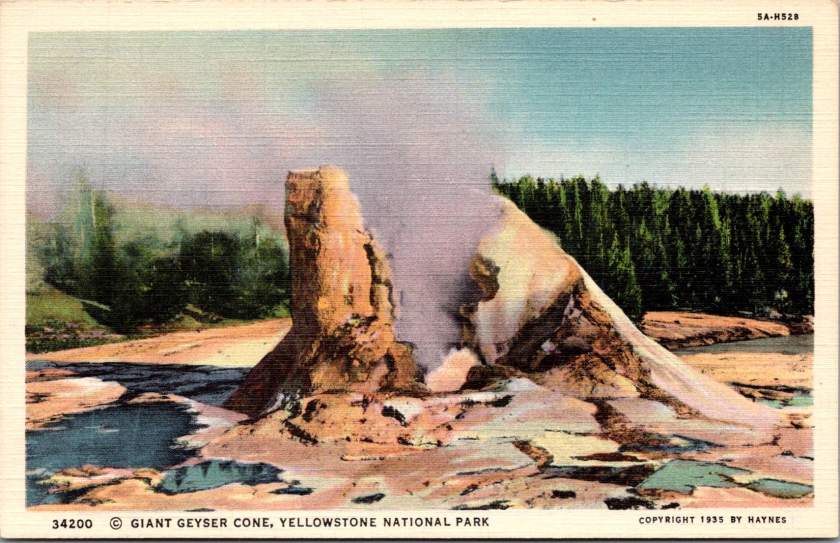

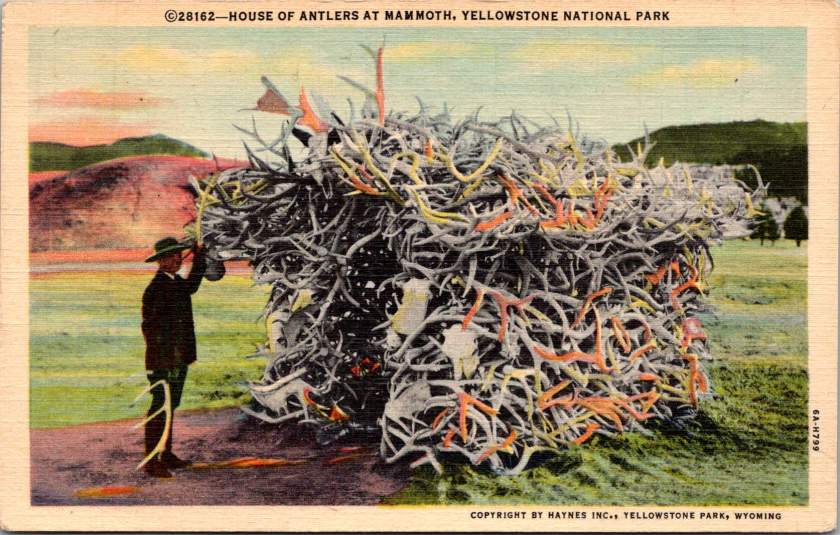

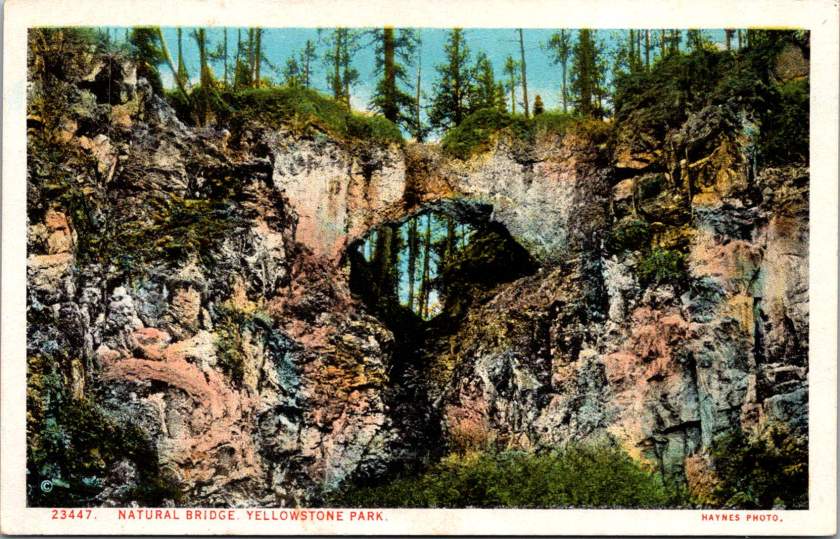

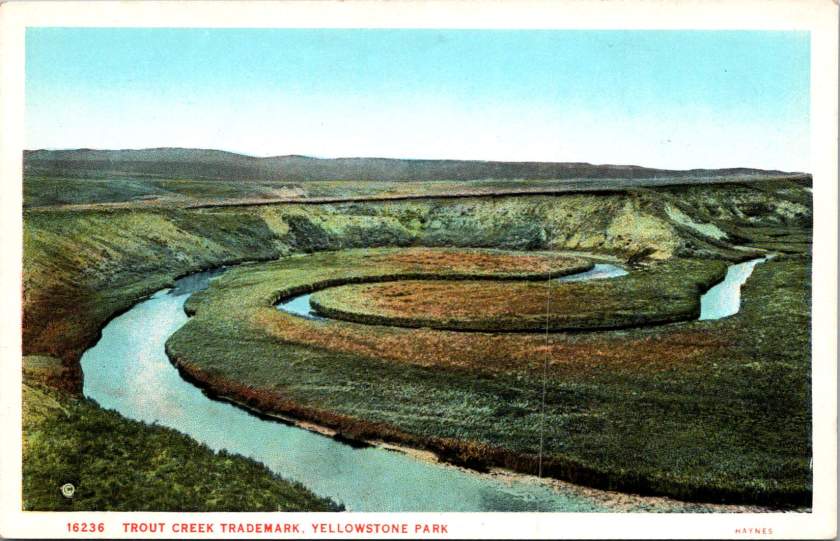

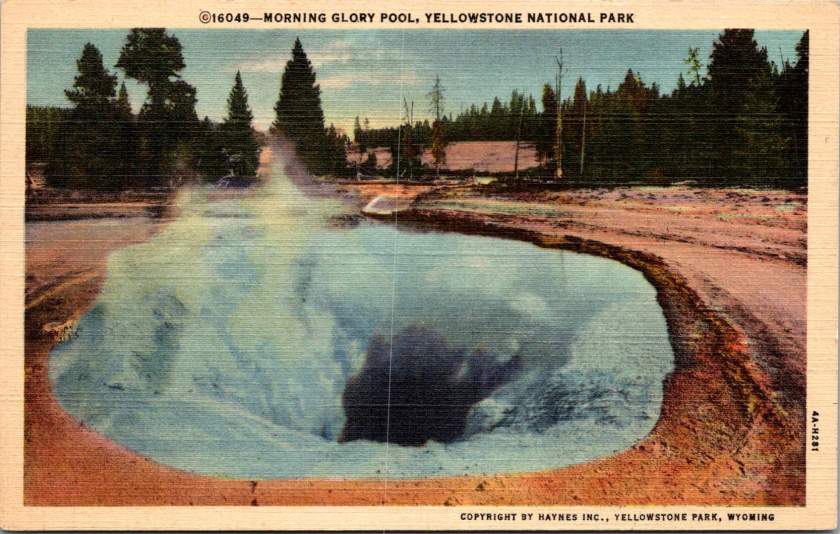

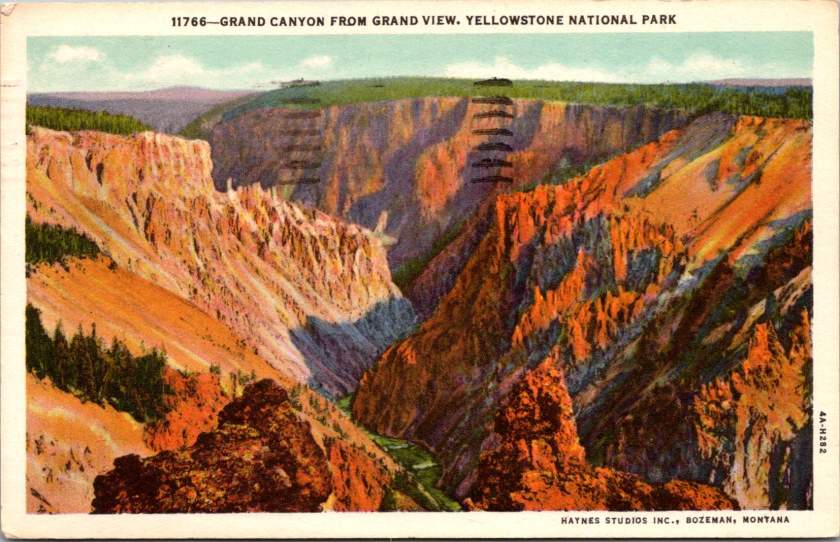

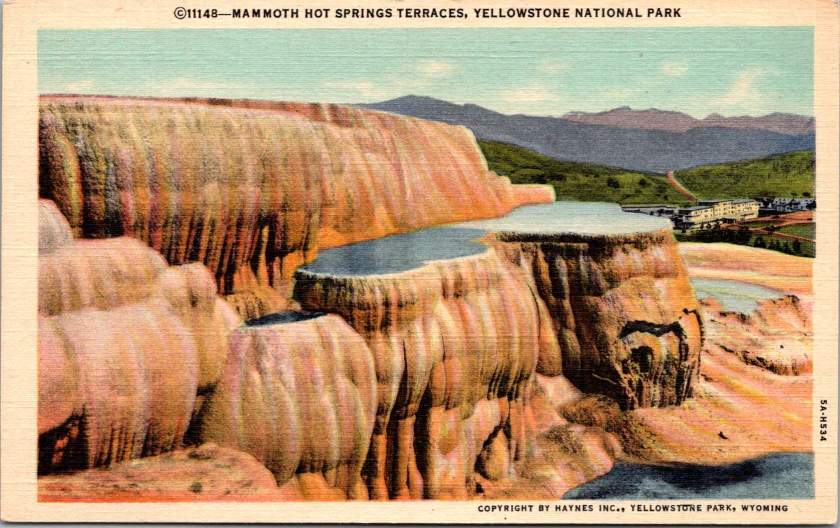

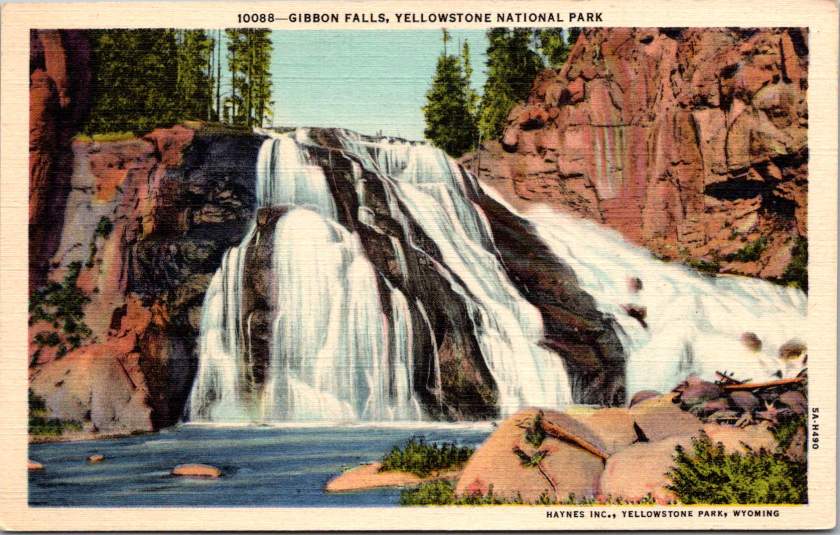

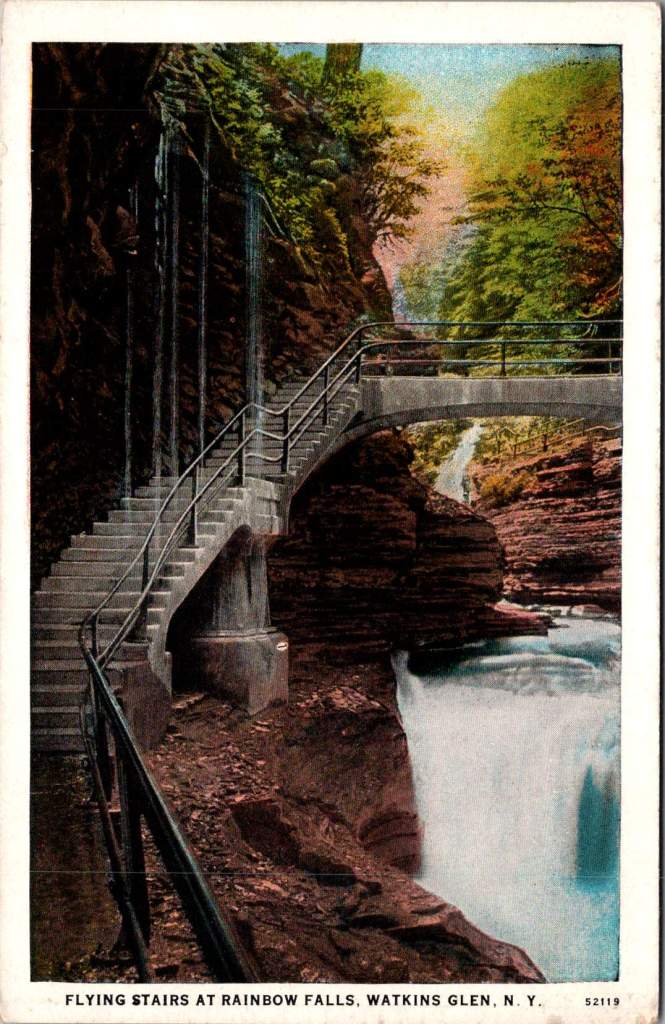

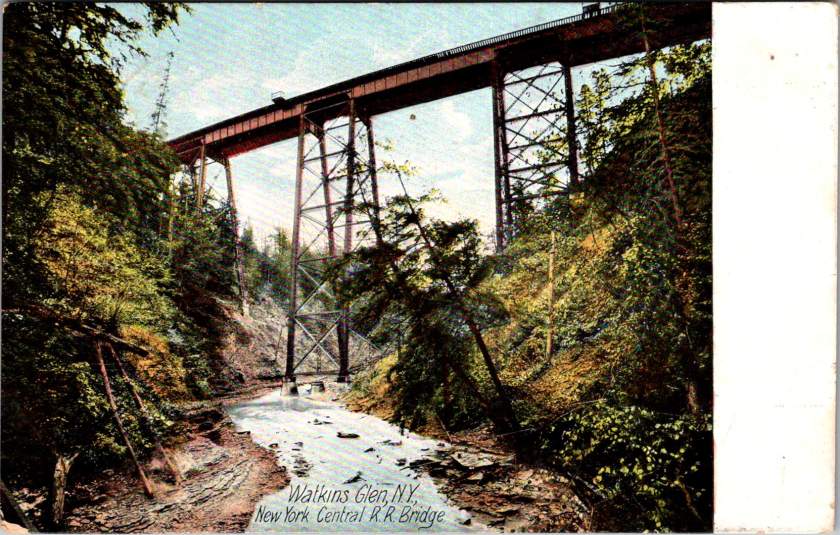

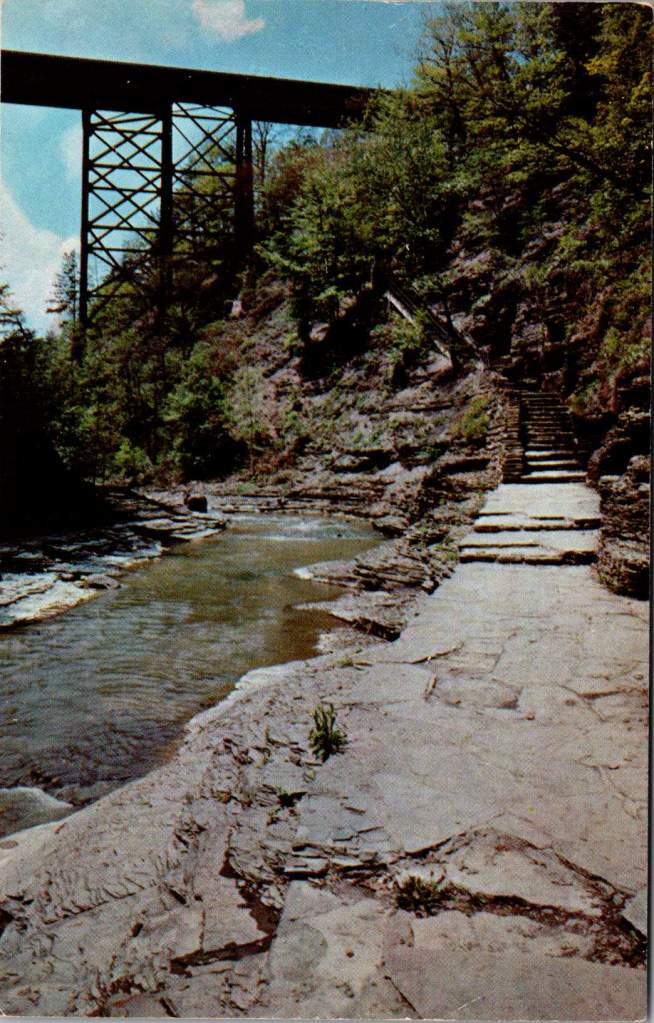

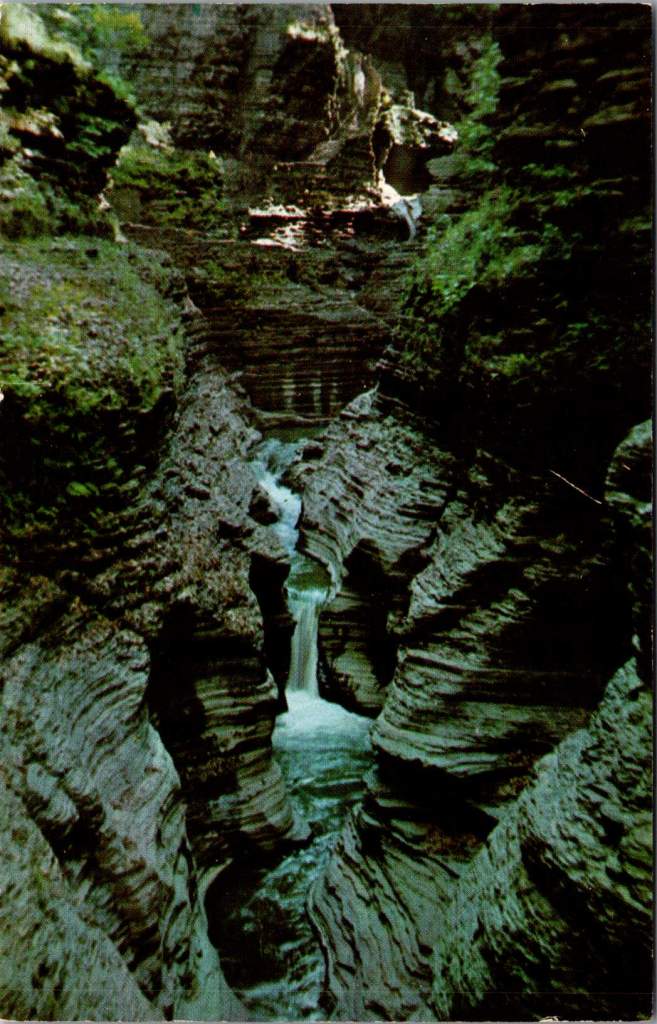

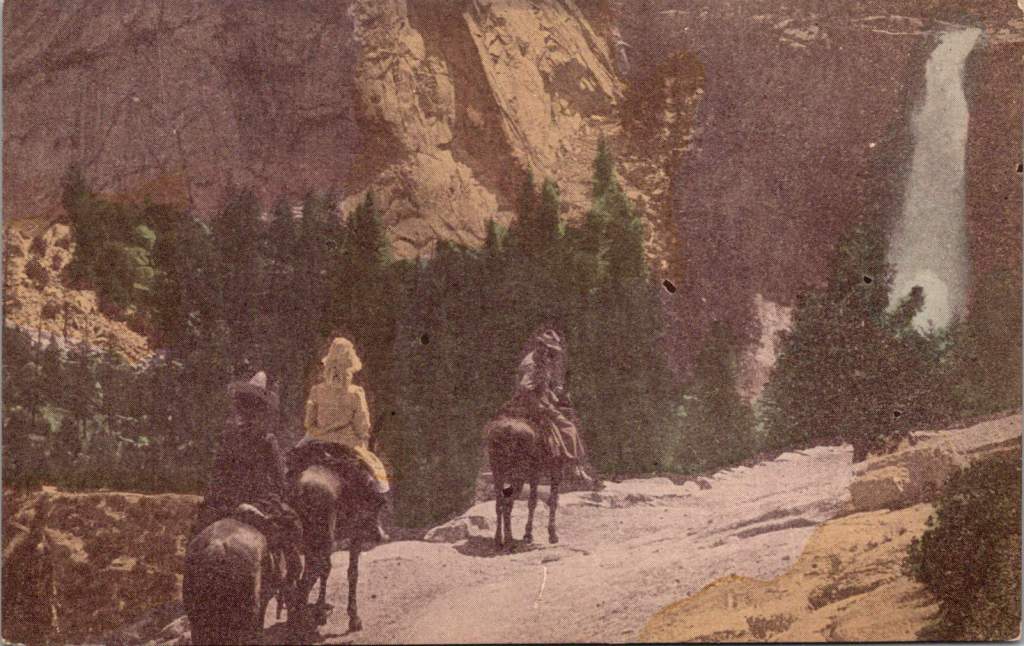

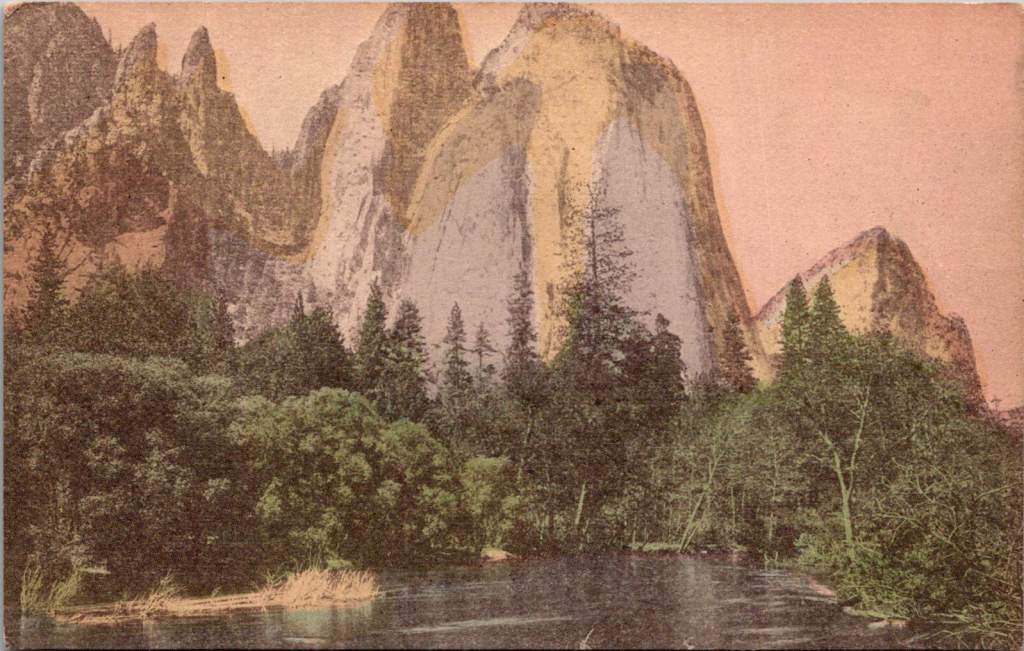

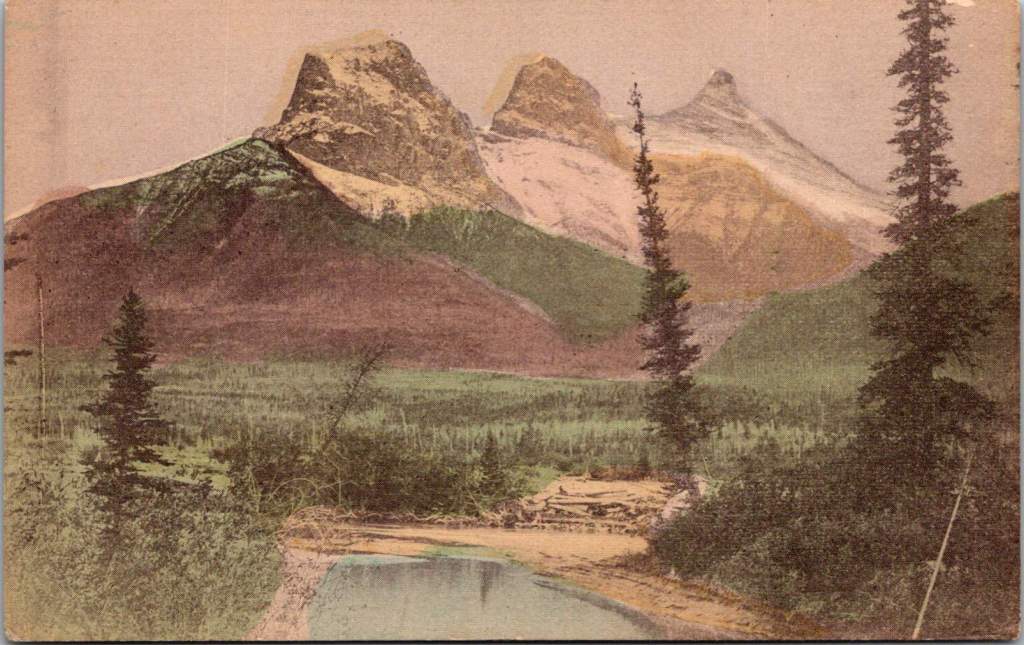

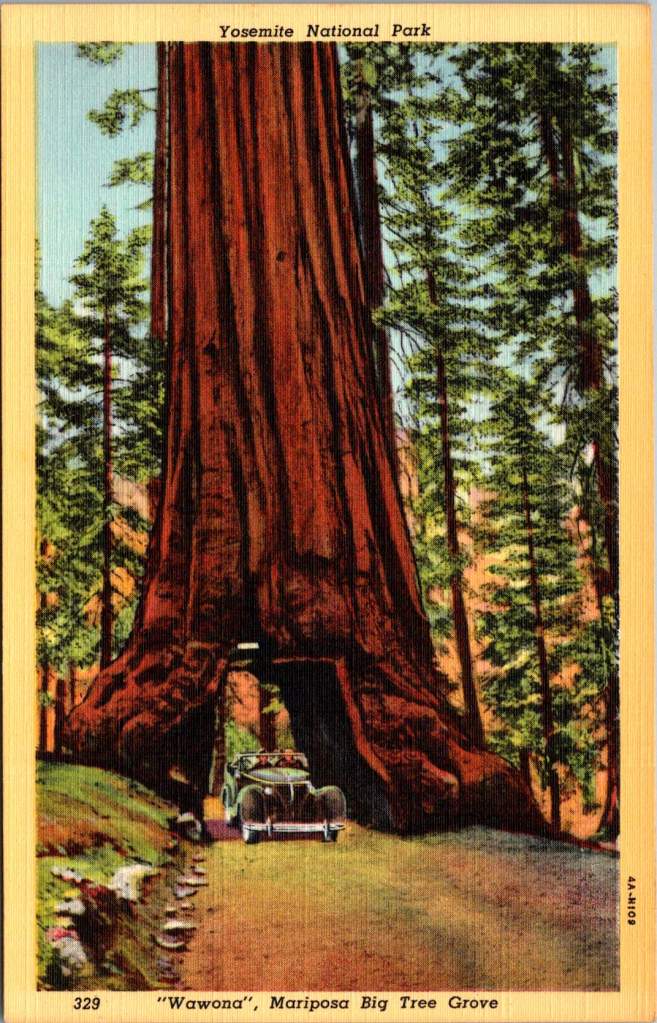

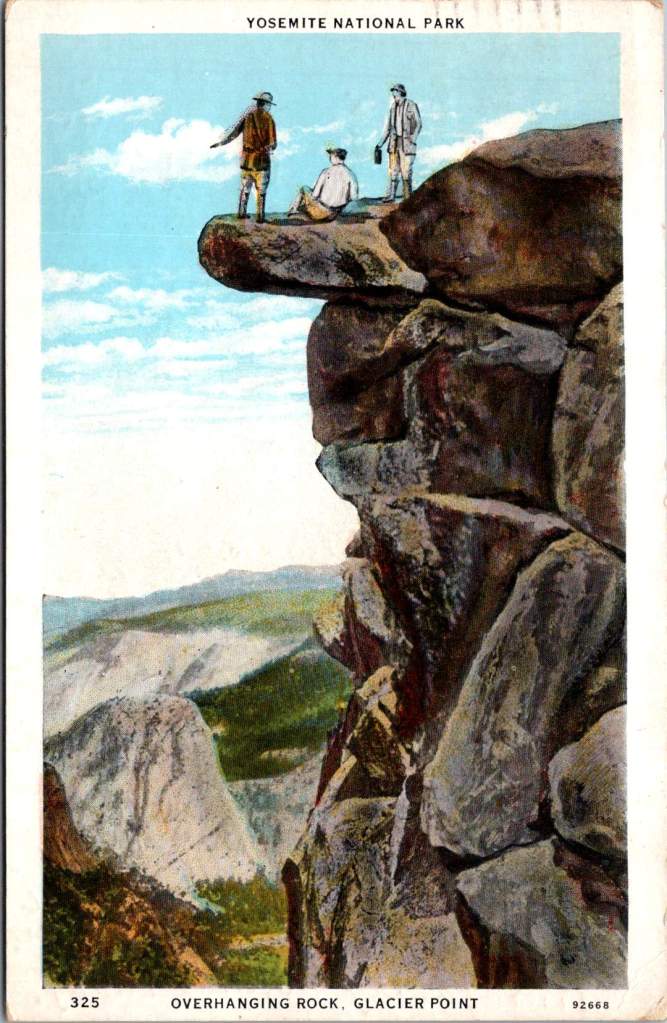

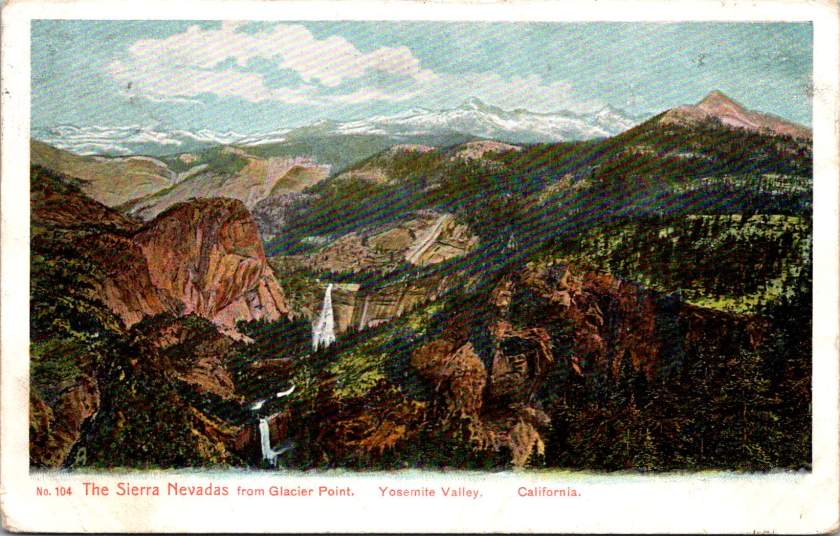

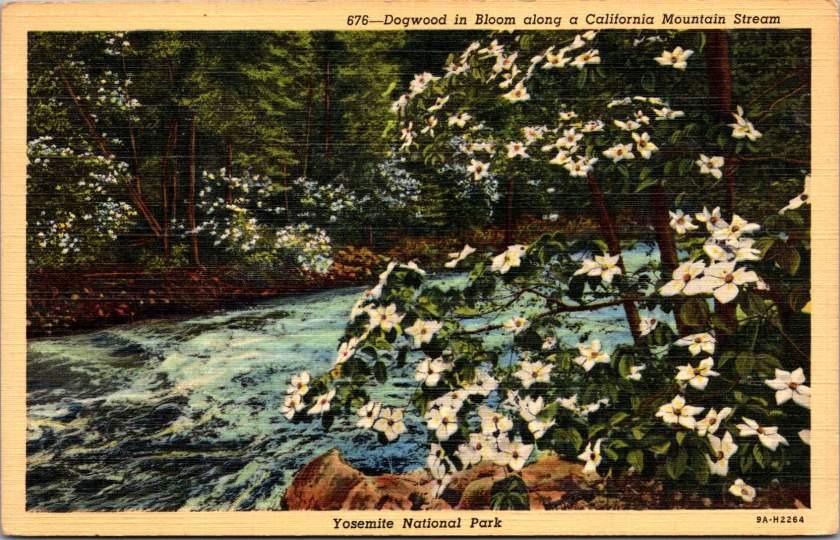

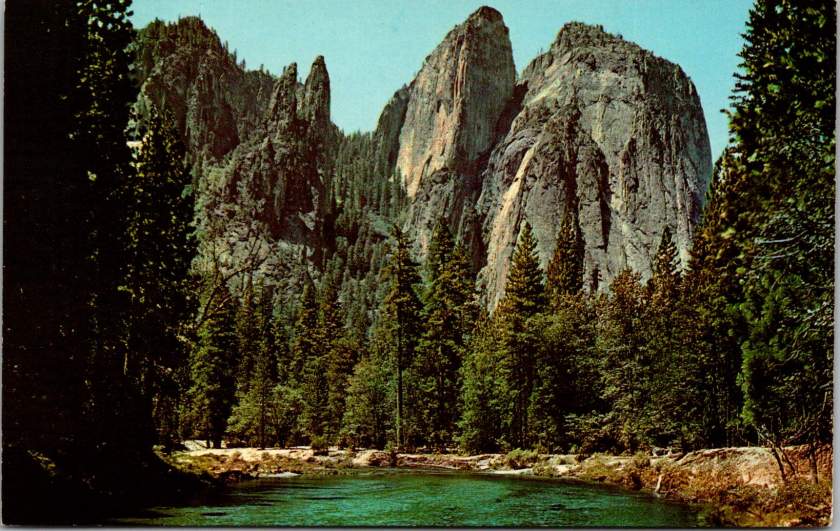

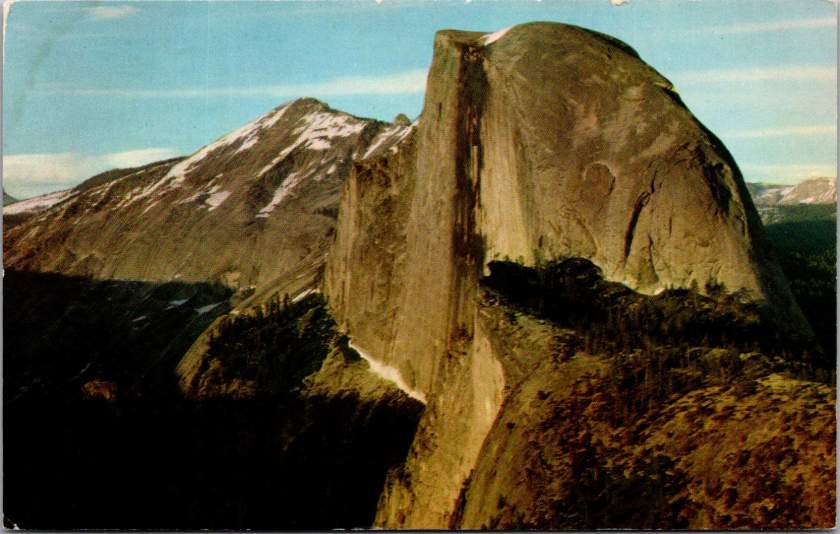

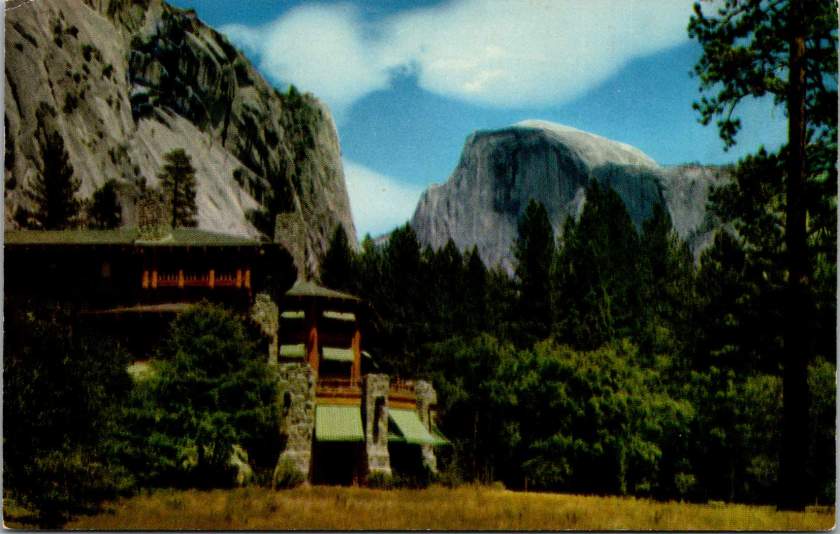

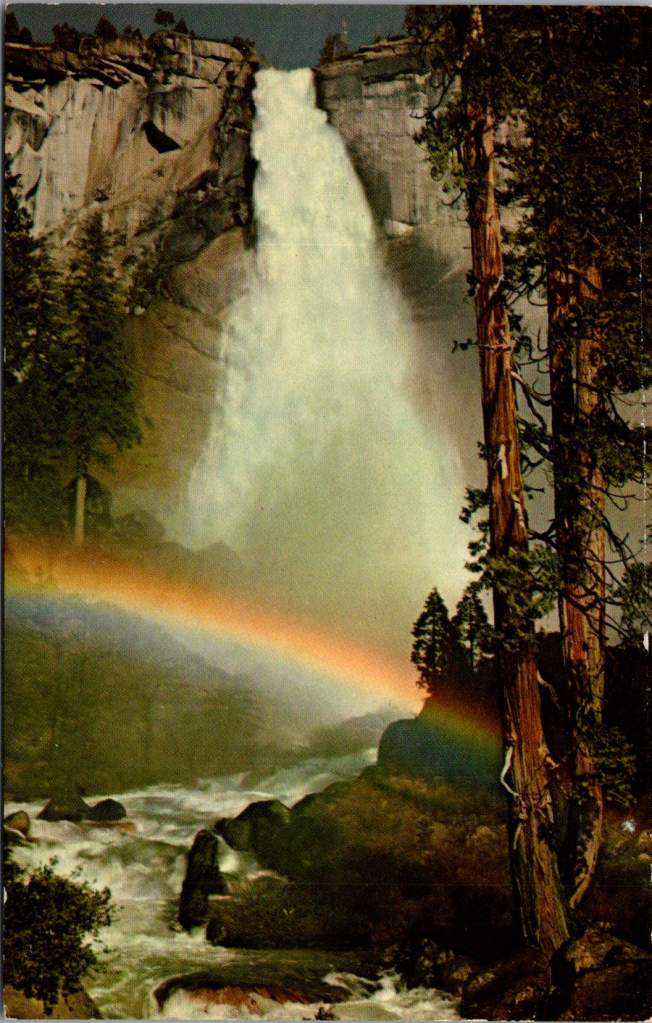

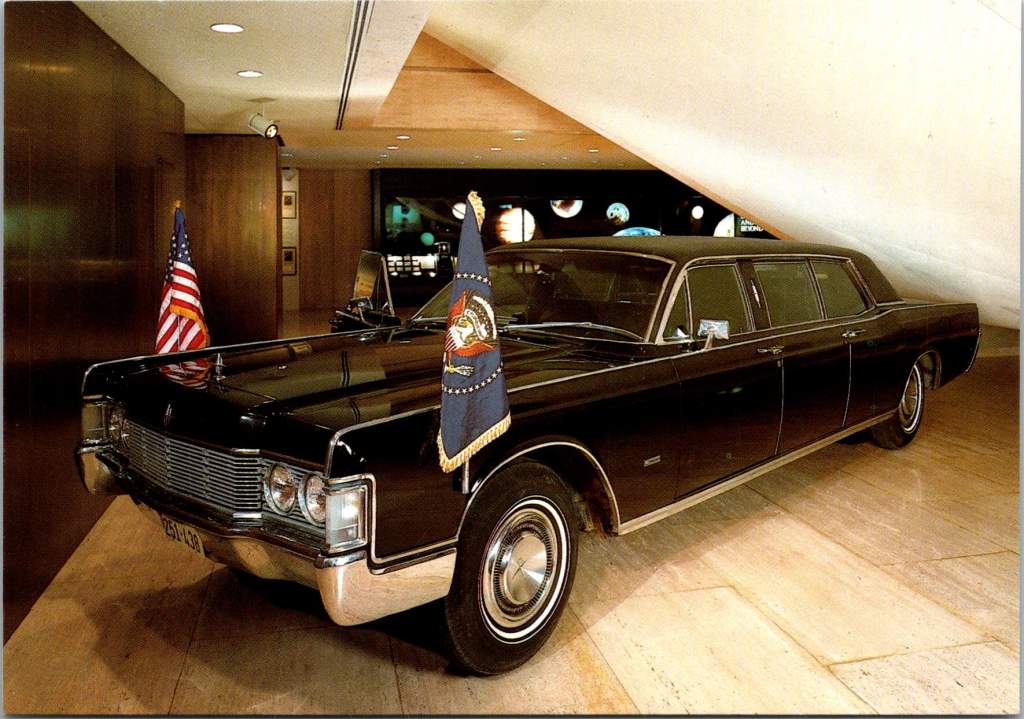

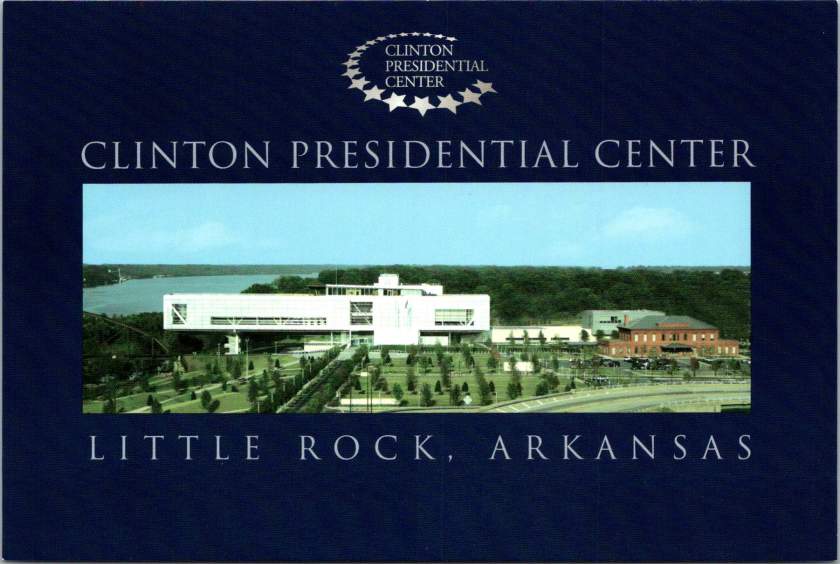

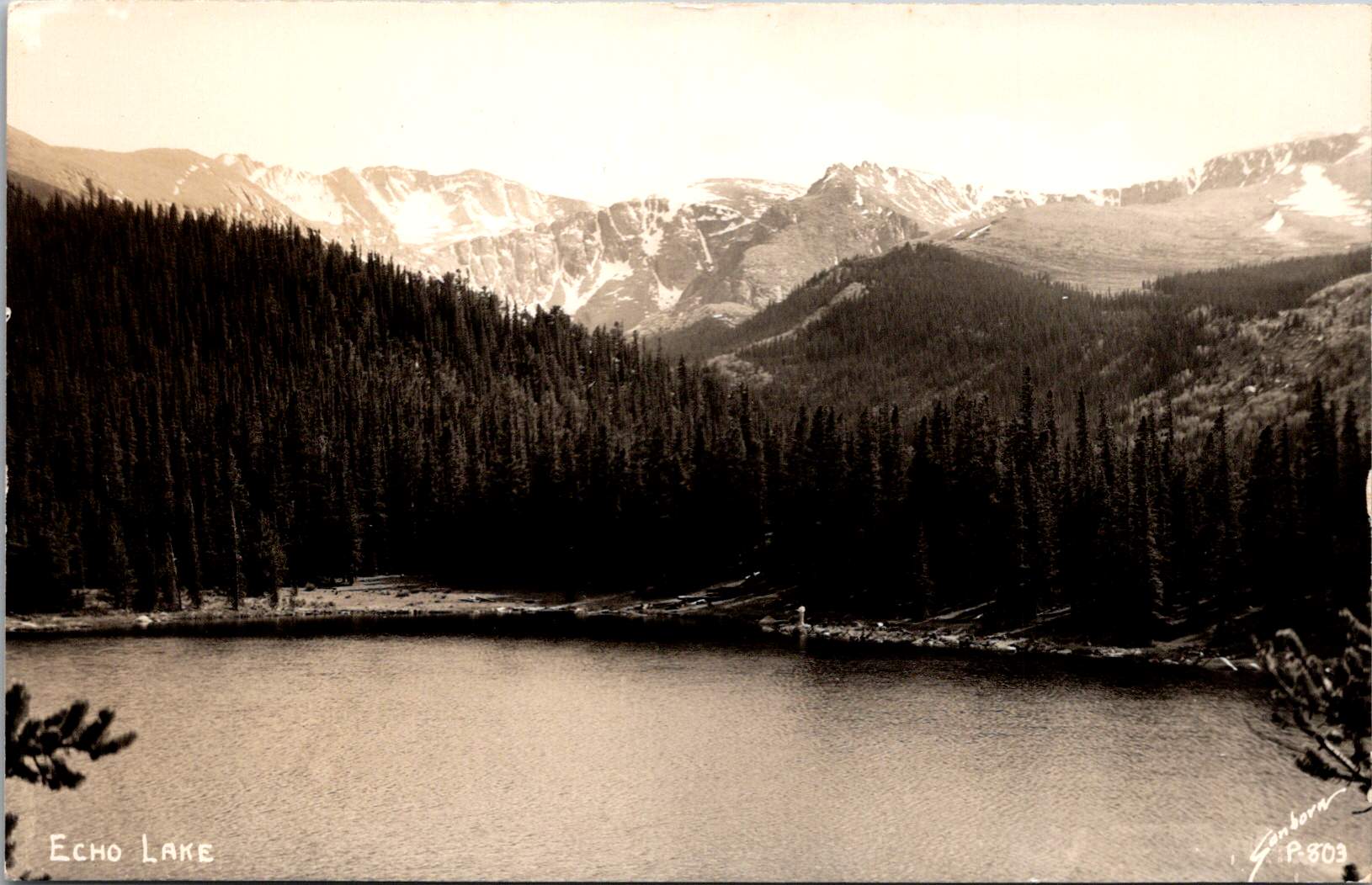

Perhaps no industry benefited more from postcards than tourism. Hotels, resorts, transportation companies, and local chambers of commerce all commissioned postcards that served as both souvenirs and advertisements. Visitor bureaus coordinated with publishers to ensure their destinations were well-represented in the marketplace. The economic impact was substantial—a scenic view postcard might cost a penny to produce, sell for a nickel, and generate hundreds of dollars in tourism revenue by inspiring visits. This multiplication effect made postcards perhaps the most cost-effective tourism marketing tool ever devised.

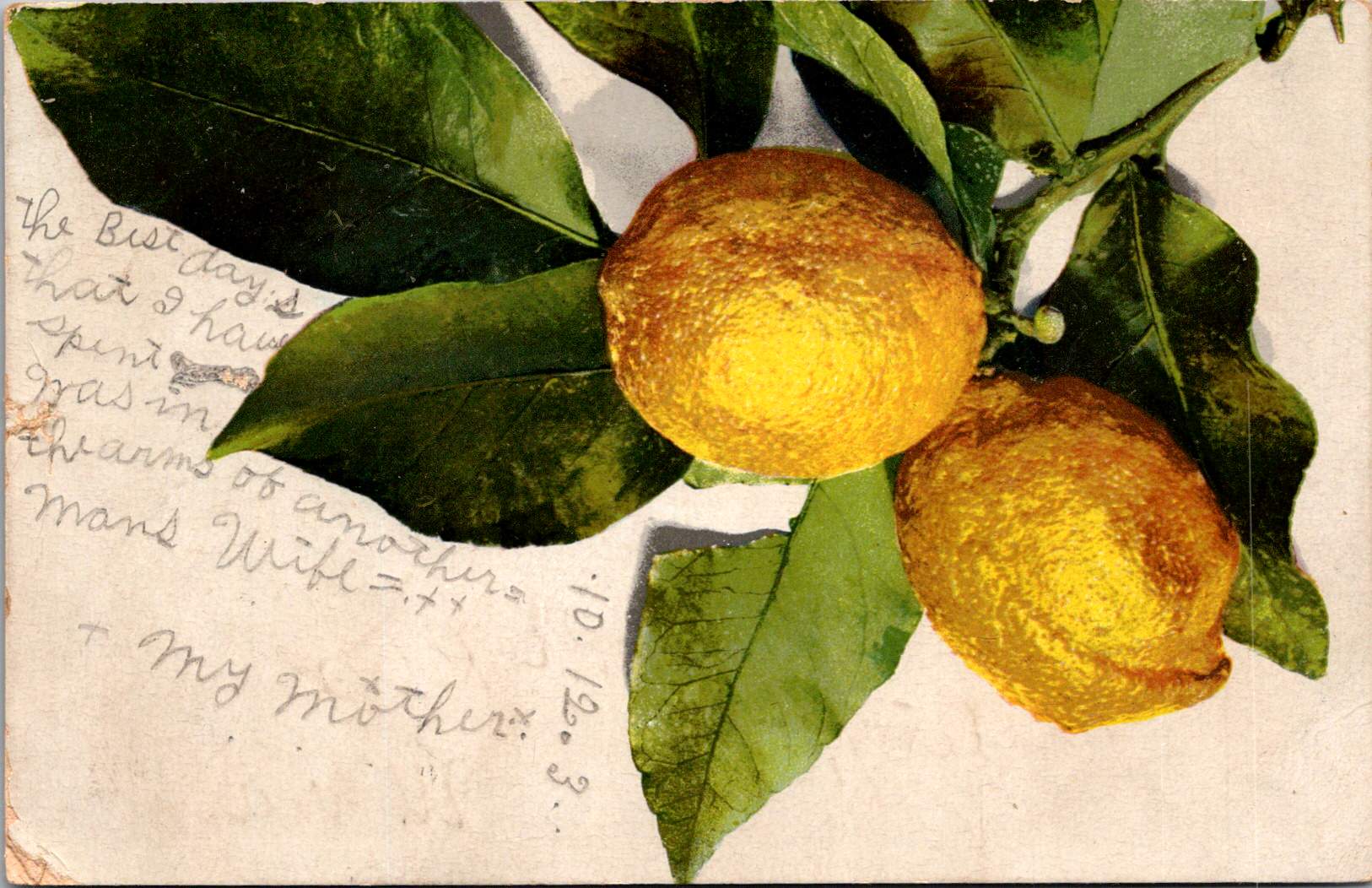

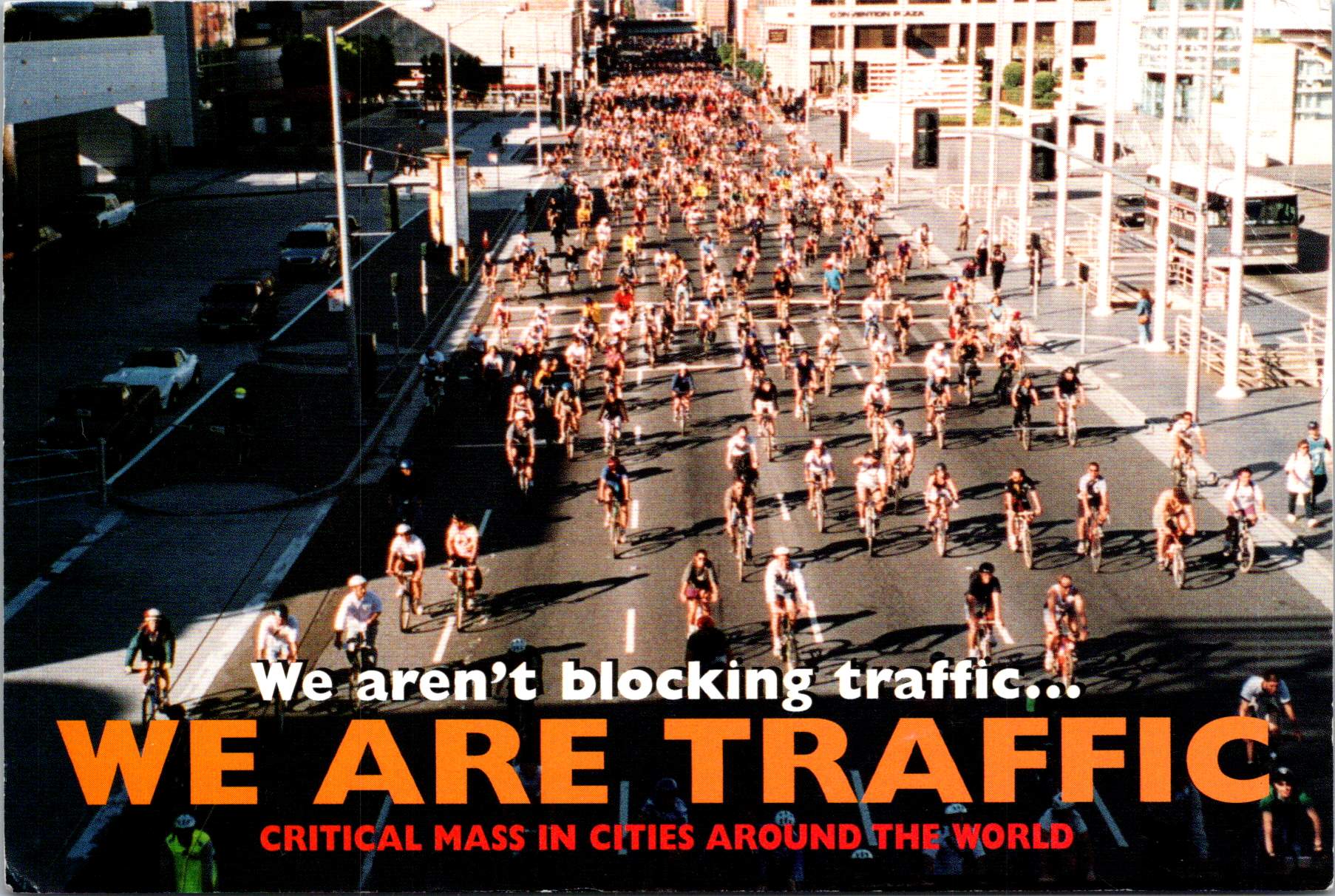

On the personal side, postcards fulfilled a spectrum of communication needs. In an era when the telephone was still a luxury and telegrams were expensive, postcards filled the gap between costly immediate communication and slower formal letters. Their affordability and efficiency made them ideal for routine messages. At half the postage rate of letters in many countries, postcards democratized written communication for working-class people who might otherwise limit correspondence due to cost. The postcard’s format encouraged brevity—a perfect medium for quick notes without the formality or length expected in a letter. In urban centers with multiple daily mail deliveries, postcards functioned almost like text messages, allowing people to make arrangements within hours.

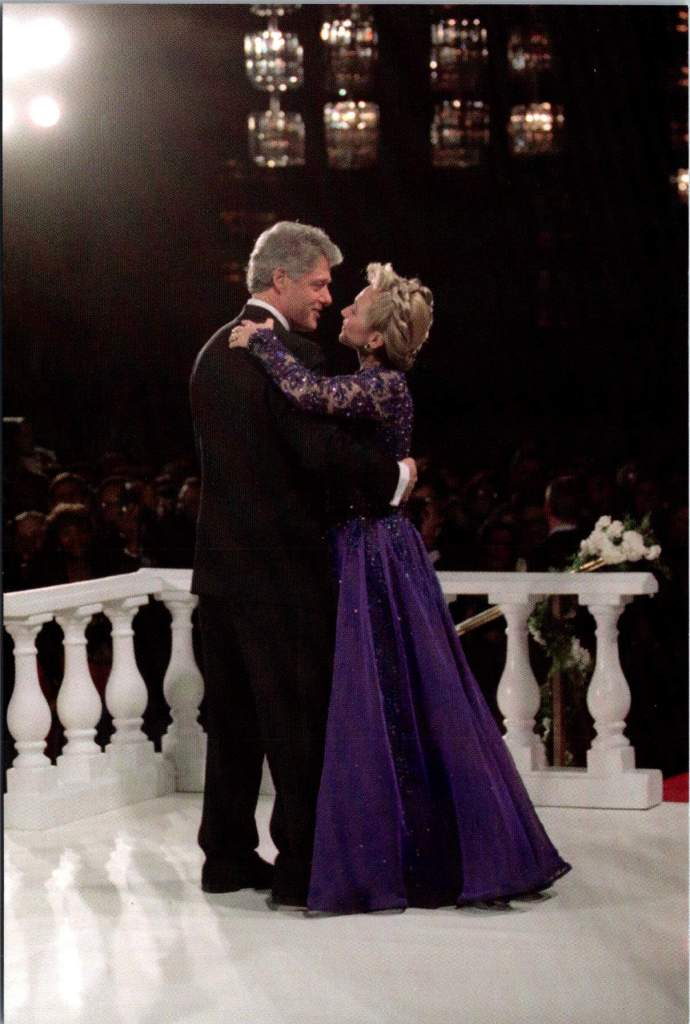

Sending postcards from vacation destinations served as tangible proof of travel experiences. “Wish you were here” cards from resorts or tourist locations signaled social status and mobility. Recipients often displayed postcards on special racks or in parlor albums, using them as affordable decorative elements and evidence of their social connections. For people who rarely traveled, receiving postcards provided authentic glimpses of distant places through real photographs rather than artistic interpretations.

Perhaps most significantly for historical purposes, postcards—especially RPPCs—documented aspects of community life that would otherwise have gone unrecorded. Local events, buildings, streetscapes, and everyday activities were captured on postcards, creating a visual record of ordinary life at the turn of the century that has proven invaluable to historians. When natural disasters or significant events occurred, local photographers would quickly produce RPPCs documenting the situation. These cards spread visual news of floods, fires, celebrations, or notable visitors throughout the region, serving an early photojournalistic function.

While American postcard production initially lagged behind Europe in quality, US companies excelled at entrepreneurial adaptation. When the 1909 Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act increased import duties on foreign postcards, American firms rapidly expanded domestic production capabilities. When World War I cut off European imports entirely, American manufacturers stepped into the gap, developing new techniques and styles.

Beyond the Golden Age

Behind every seemingly simple postcard lies a complex history of industrial innovation, international cooperation, and social transformation—a paper-based predecessor to the digital networks that connect us today.

The Golden Age of postcards waned after World War I due to disruption of European production centers, rising postal rates, the growing popularity of telephones, and the emergence of new forms of mass media.

The era when postcards emerged was a crucial moment when ordinary people gained access to new visual communication tools. The democratization of image sharing pioneered by postcards foreshadowed later developments in visual communication. This visual history reminds us, from personal photographs to social media posts, the impulse to share visual snippets of our lives is a constant across time.