As American cities boomed in the early 1900s, panoramic postcards emerged to document their transformation. The Haines Photo Company of Conneaut, Ohio seized this opportunity, operating from about 1908 to 1917. Photographers crisscrossed the country capturing these distinctive wide-angle views of evolving American cityscapes, like Phoenix, a fledgling desert outpost poised for dramatic growth.

Phoenix in 1900 numbered just 5,554 residents. Though small, it already served as Arizona’s territorial capital with statehood just twelve years away. These panoramic postcards reveal a city establishing the foundation for its explosive future growth.

Washington and First Streets

The first panorama captures Phoenix’s commercial core at Washington and First Streets. Electric streetcar tracks cut through the unpaved road—these trolleys had replaced horse-drawn versions in 1893, modernizing city transit. Desert mountains loom in the distance while palm trees line parts of the street, evidence of successful irrigation in this arid landscape.

A prominent building with a tower dominates the background. Pedestrians stroll the sidewalks alongside horse-drawn carriages, as automobiles remained rare luxuries. Sturdy two and three-story commercial buildings reveal a city with ambitions beyond its frontier origins.

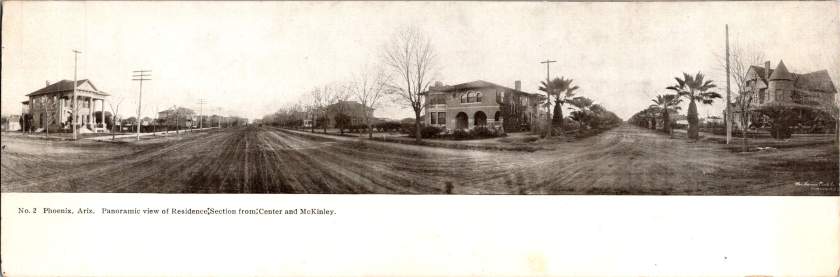

Residences at Center and McKinley

The second view shifts to Phoenix’s growing residential district at Center and McKinley. Here, successful merchants and professionals built impressive homes along wide, unpaved streets. Both palm trees and deciduous trees (some leafless in winter) frame the elegant residences.

These neighborhoods developed as streetcar suburbs, allowing prosperous residents to escape downtown congestion while maintaining business access. Homes display fashionable Colonial Revival and Craftsman styles with generous porches and elaborate details. Unlike cramped eastern cities, Phoenix boasted detached homes on spacious lots—a pattern that would define its future growth.

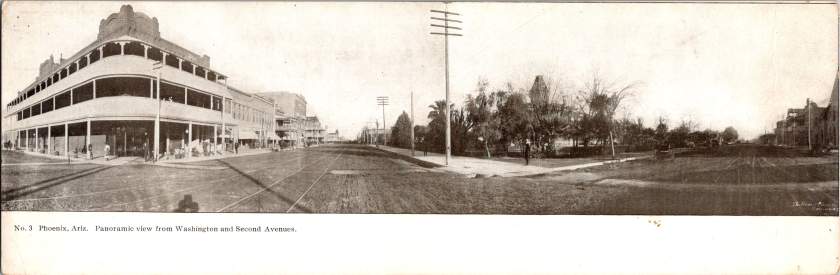

Washington and Second Avenues

The third panorama returns us to the commercial district. A substantial three-story building with multiple balconies dominates the left side. Was it a hotel or major retailer? Streetcar tracks again slice through the broad dirt roadway. A park or green space appears across the street, providing rare desert shade.

Notice the shadow intruding on the lower left? It’s the silhouette of our photographer with tripod-mounted camera. Was this F.J. Bandholtz, a prominent panoramic photographer who worked with Haines?

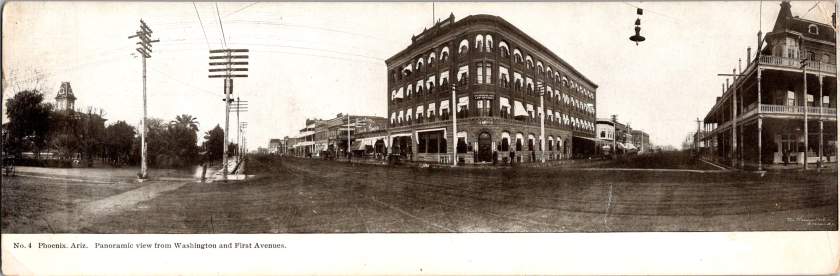

Washington and First Avenues

The fourth panorama captures Phoenix’s financial center. A four-story brick building with numerous arched windows dominates the scene. This building houses the Phoenix National Bank with law offices above, very likely belonging to Joseph H. Kibbey, a former Territorial Supreme Court Justice (1889-1893) and Arizona Territorial Governor (1905-1909).

Founded in 1892, the Phoenix National Bank had become Arizona’s largest by 1899, with deposits totaling $692,166. Telegraph and electrical poles with multiple crossbars line the street, demonstrating developing infrastructure. The dirt streets accommodate both pedestrians and horse-drawn vehicles, though automobiles were beginning to appear.

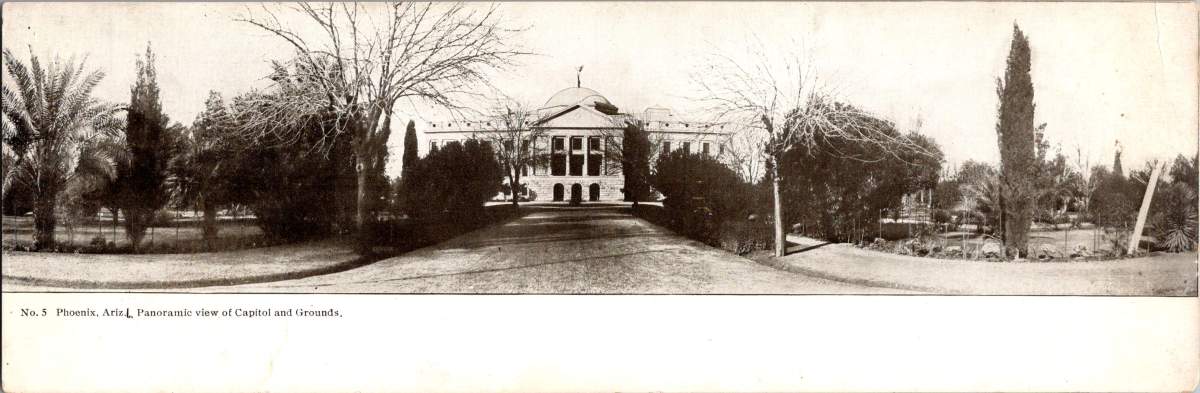

Capitol Grounds

The fifth panorama showcases Arizona’s territorial capitol. This impressive domed structure, completed in 1900 at a cost of $130,000, sits back from the road on a donated 10-acre plot at Washington Street’s western end. Formal gardens with cypress, palms, and ornamental plantings surround the building, irrigation transforming these arid landscapes.

Governor Murphy dedicated the building on February 25, 1901. At the time, the capitol complex embodied Phoenix’s civic ambitions and push toward statehood. Now the main building is home to the Arizona Capitol Museum, connecting present-day Phoenix to its territorial roots.

Phoenix Indian School

The final panorama depicts the Phoenix Indian School campus with its multiple buildings, some with smoking chimneys, surrounded by palm trees. Established in 1891, this federal boarding school implemented the government’s brutal and coercive Native American assimilation policies. Located on 160 acres north of downtown, the campus featured brick and frame buildings for classrooms, dormitories, workshops, and administration.

The school expanded rapidly from 42 students initially to 698 by 1900, representing 23 tribes from across the Southwest. Operating until 1990, the school’s complex history reflects the often painful relationship between the federal government and Native peoples, and Phoenix’s role in executing national policies.

The Haines Photo Company

These remarkable panoramic images came from the Haines Photo Company of Conneaut, Ohio. From 1908 for about a decade, they specialized in wide-angle photography of towns and cities across the United States. The Library of Congress preserves over 400 of their photographs documenting America’s evolving landscapes and cityscapes.

Technological innovations in cameras and film made panoramic photography possible. Companies like Haines used specialized equipment to capture expansive views with exceptional clarity. They printed these as postcards for both tourists and locals proud of their developing communities. The panoramic format perfectly suited sprawling western cities like Phoenix that grew horizontally rather than vertically.

Who actually pressed the shutter remains mysterious. The Library of Congress identifies F.J. Bandholtz (Frederick J. Bandholtz, born circa 1877) as a prominent panoramic photographer working with Haines. The shadow in the third image provides our only glimpse of the person behind the camera—a tantalizingly incomplete clue to their identity.

Fast Growth in Phoenix

The early 1900s transformed Phoenix through several key developments. Roosevelt Dam (completed 1911) secured reliable water and power for the Valley. The Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway (1895) connected the city to northern Arizona while streetcars improved local mobility. Institutions like the Carnegie Free Library (1908) and Phoenix Union High School (1895) established cultural foundations. Economic activity diversified beyond the “Five Cs” (copper, cattle, climate, cotton, and citrus) to include banking, retail, and professional services.

Statehood on February 14, 1912 elevated Phoenix’s status as capital. These postcards hint at those century-old aspirations—a frontier town rapidly becoming a modern American city. Phoenix’s population doubled from 5,554 in 1900 to 11,134 by 1910, and surged to 29,053 by 1920, launching a growth trajectory that would eventually make it one of America’s largest cities.