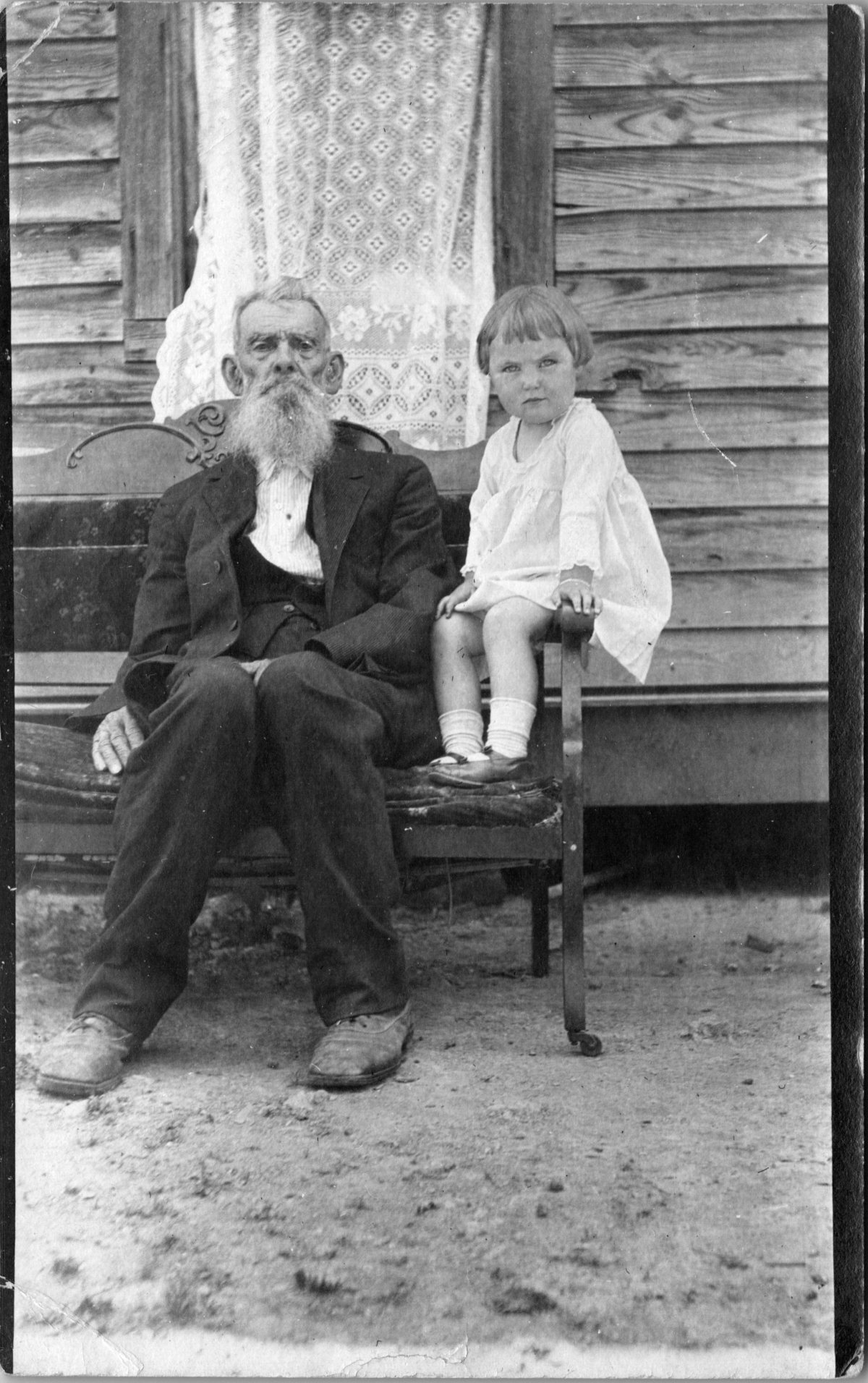

We look back at them, and they return the gaze. Their stories blend with our own memories and imagination. They begin to feel like someone’s ancestors, though the particulars remain elusive.

Rochester in Rearview

In 1877, photography required glass plates, wet chemicals, heavy equipment, and specialized knowledge. George Eastman, a frustrated bank clerk from a poor family in Rochester, taught himself the process in his mother’s kitchen.

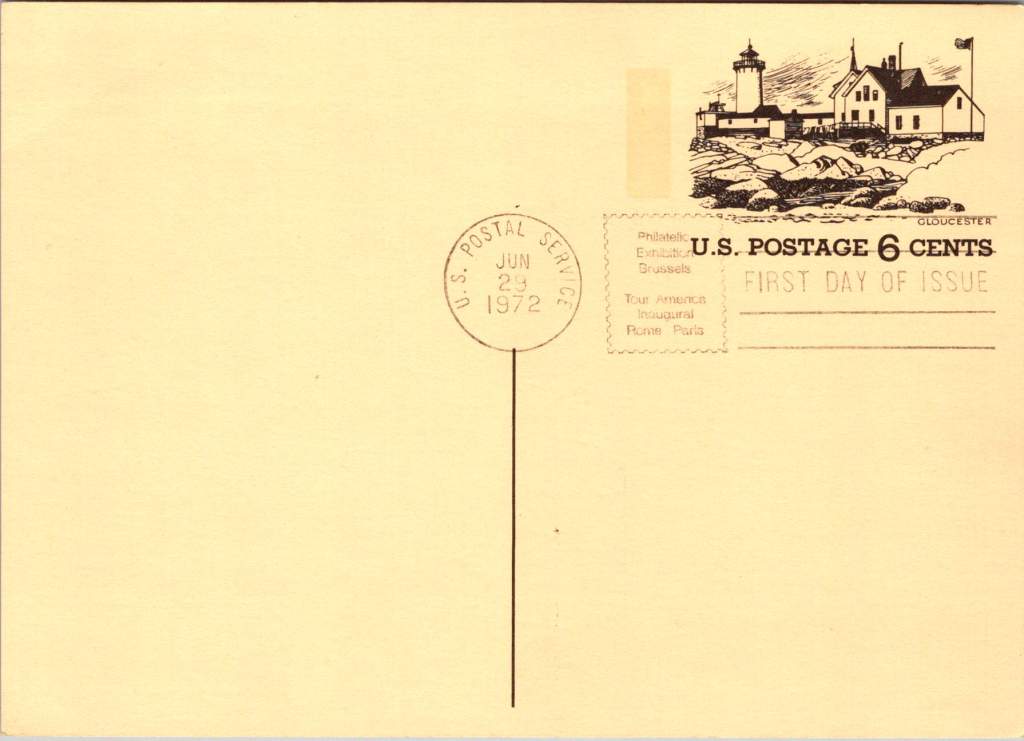

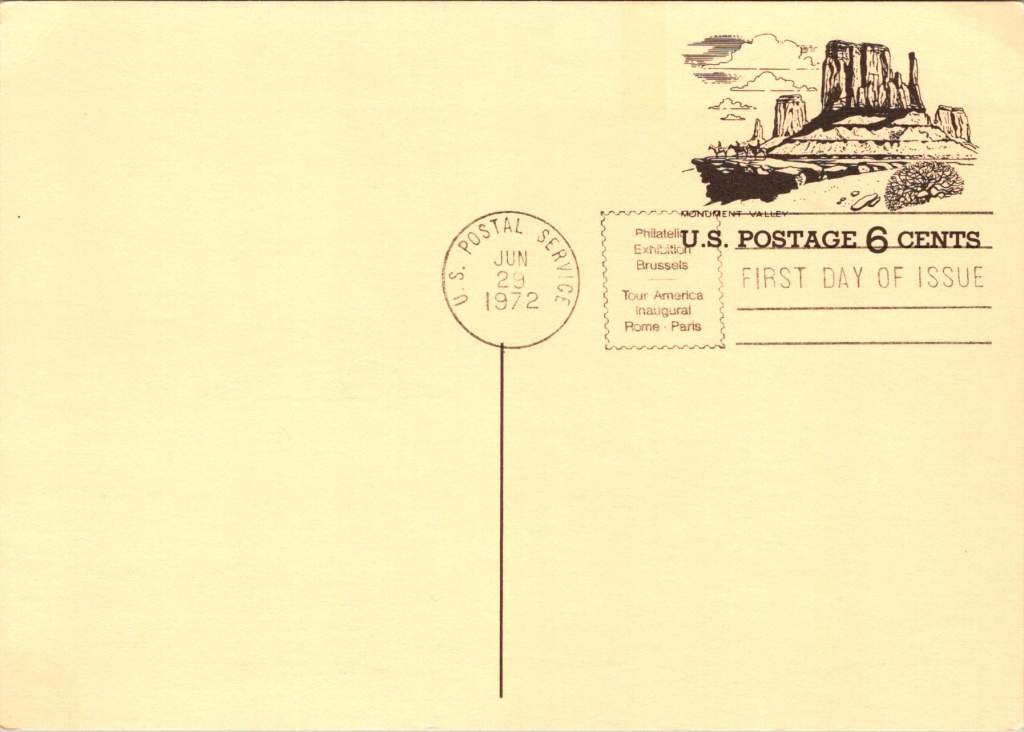

A decade later, Eastman had invented a simple camera pre-loaded with film for 100 exposures. By 1903, the Eastman Kodak Company released the 3A Folding Pocket Camera with 3¼ × 5½ inch film—exactly postcard size and pre-printed on the reverse. Local photographers and home enthusiasts could contact-print the negative directly onto postcard paper. No enlarger needed, and simplified processing equipment and chemicals.

Rochester became an ecosystem. Bausch & Lomb made the lenses. Kodak manufactured the cameras, bought the film company, and controlled the processing. Customers shipped the entire camera unit back to the factory, and received prints and a pre-loaded camera in return. “You press the button, we do the rest.” Factory workers were the first to witness an era of American life, as images of farms, houses, banks, theatre, and towns and their inhabitants poured in.

A quiet man, Eastman watched this unfold from the center, as his invention changed history and rippled through culture. By 1920, millions of Americans owned cameras. Eastman left a simple note when he ended his own life at 77 and in degenerative pain, “To my friends: My work is done. Why wait? GE”.

What We See

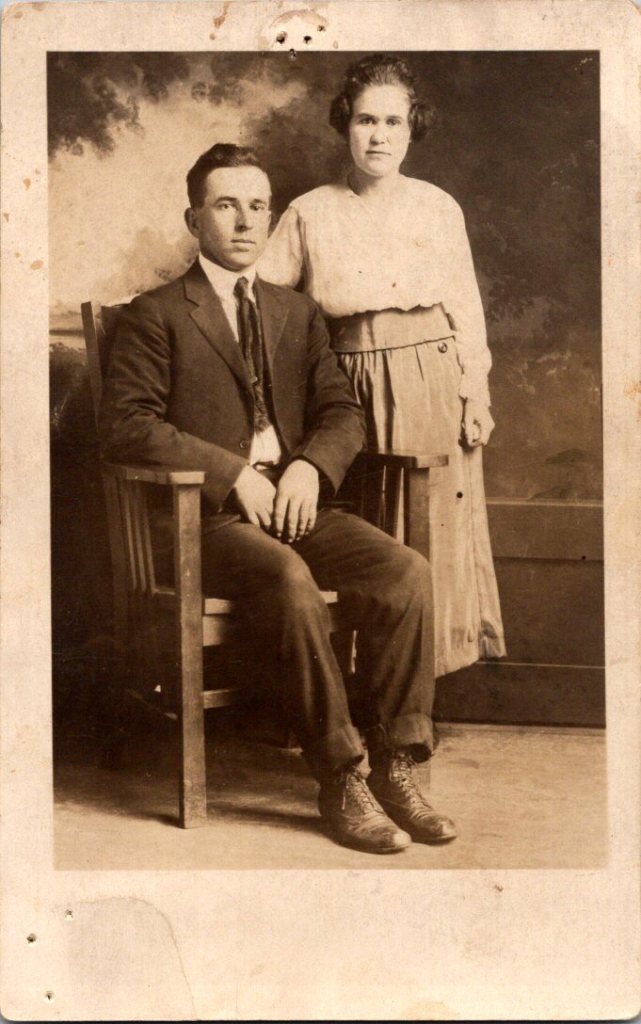

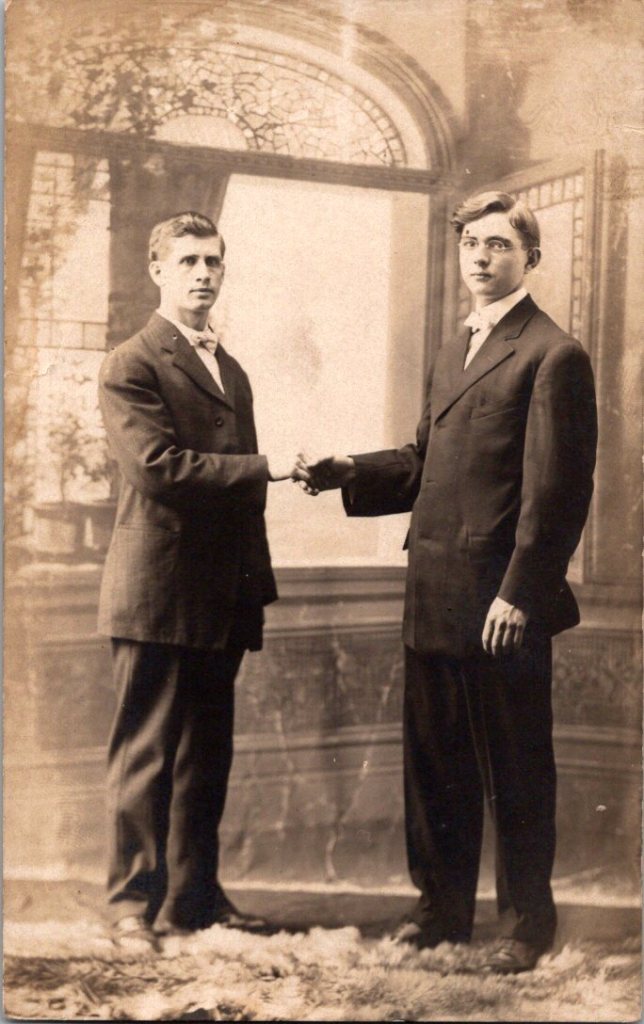

The studio portraits above show painted backdrops—ornamental arches, garden trellises. The lighting is controlled. Poses held steady. Technical quality consistent. These were made by professionals charging by the sitting.

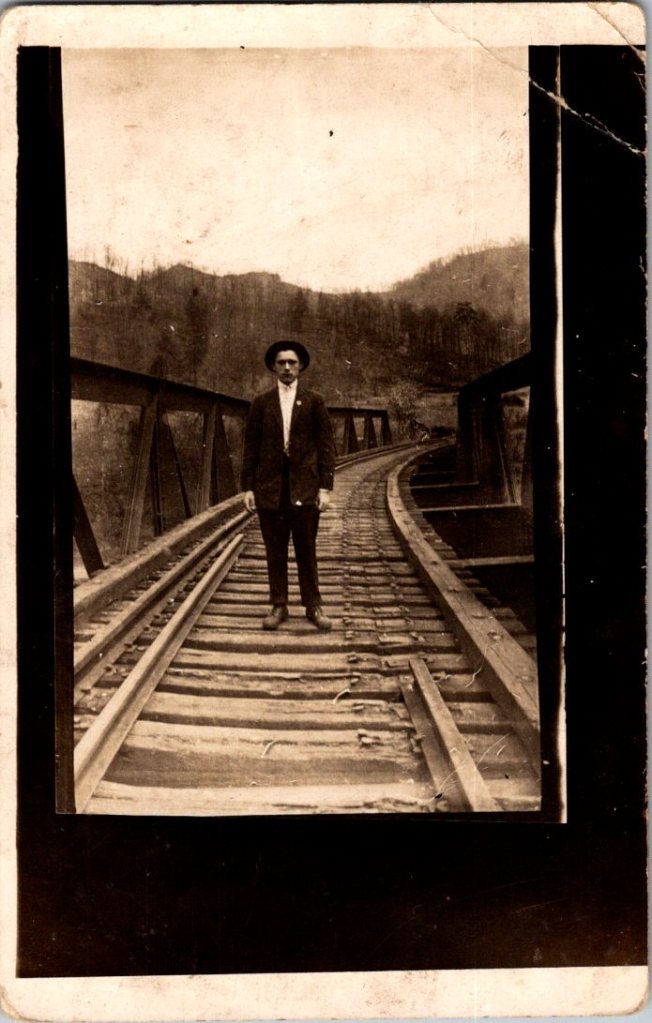

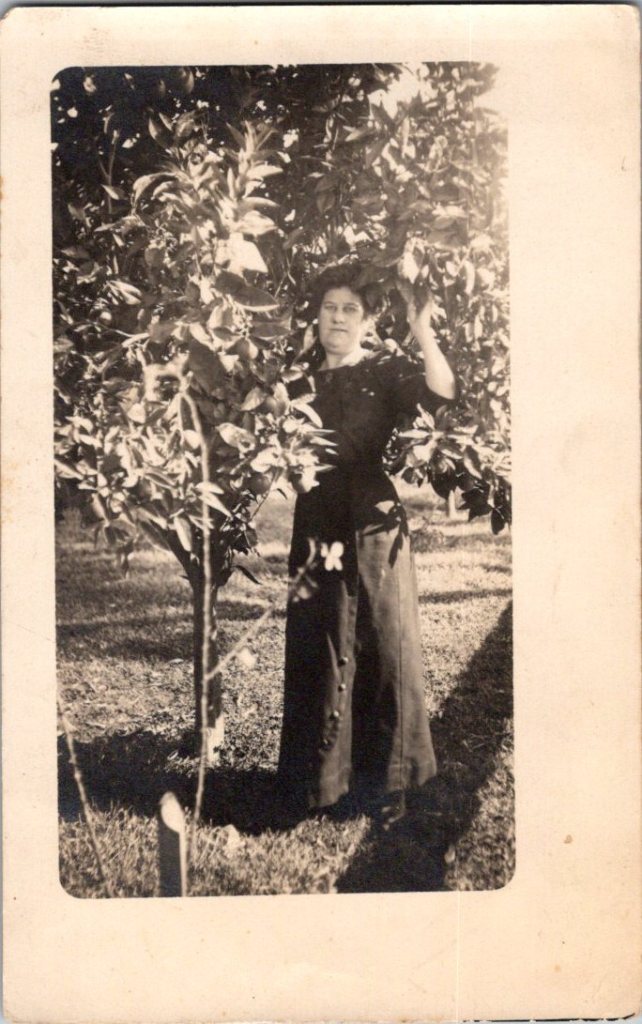

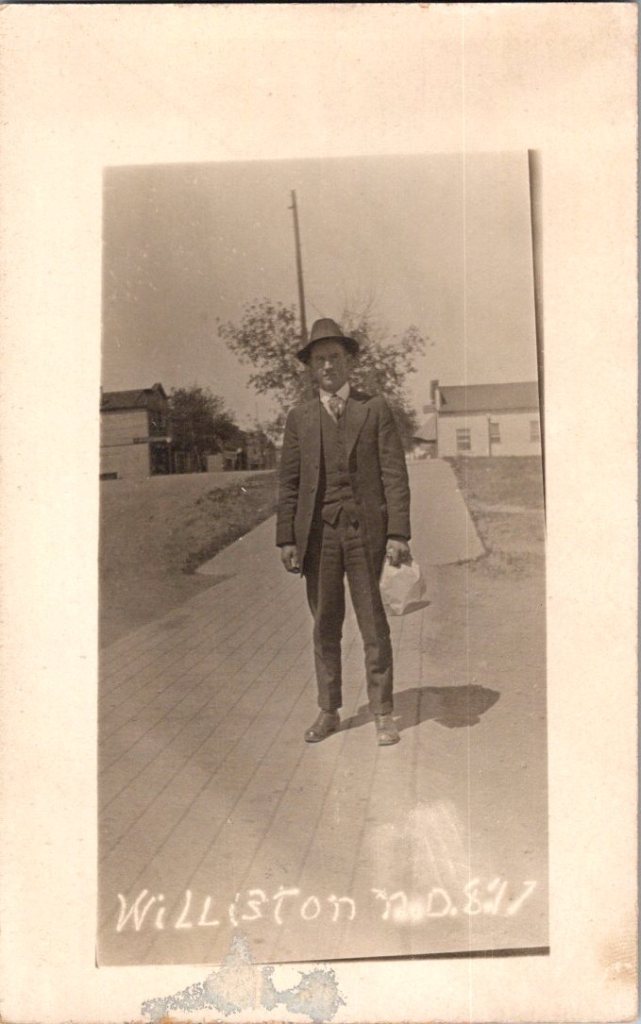

The outdoor snapshots show real places—porches, orchards, dirt roads. Natural lighting, sometimes harsh. Composition varies from confident to awkward. These came from camera owners of varying skill. The irregularities in frame and exposure suggest they were developed at home, too.

What We Don’t See

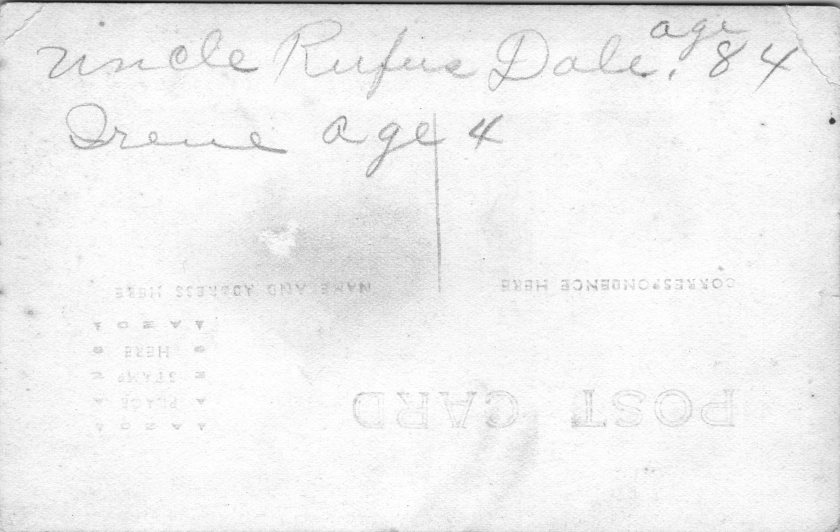

Despite the pre-printed paper and earnest intent, real photo postcards were rarely sent as such. A few have difficult script, cryptic addresses, faded cancellations, and worn stamps.

“Hello Fanni. Miss Fanni Moore, Panhuska, Okla.”

The remaining relics haven’t been labeled, addressed, or mailed. Most backs are blank, and they were often collected in photo albums. The manufacturing marks may have been quite incidental.

What’s missing from nearly all: names. Very few clues to subjects, locations, dates. The people who made these photographs knew who everyone was. They didn’t need labels. Or, perhaps they were accompanied by letters and mailed in envelopes for privacy and protection.

A century later, the faces remain potent but anonymous. We guess at relationships from physical similarity, from who stands near whom. Sometimes we’re right. Sometimes, we can’t believe our eyes.

Spaces in Between

The 3A Folding Pocket Kodak cost $20-30, equivalent to $600-900 today. An expensive hobby, but accessible to prosperous farmers, small business owners, middle-class families. Film cost about 50 cents per roll.

The investment meant something, whether it was the equipment or the studio session. People photographed what mattered—children, homes, gatherings. The images document their priorities, and their time passing.

Real People, Real Limits

These are real people who lived, worked, loved, died. Someone cared enough to preserve their images. They matter still, in part, because they mattered to someone before.

But our analysis stops here. We can describe what we see—the composition, the technical choices, the historical context. We can note patterns across the collection. We can explain how the technology worked and who had access.

The work of naming and placing, in particular, belongs to families searching their own histories, connecting faces to stories passed down, matching photographs to genealogical records. Those searches have their own purposes, their own meanings.

We are collectors examining patterns, not descendants reclaiming ancestors. Though, it is tempting.