The Golden Age of Postcards, spanning roughly from 1898 to 1918, was a period when billions of postcards crisscrossed the globe, connecting people and places in ways never before possible. These seemingly ordinary objects open a window into a time when the world was simultaneously expanding and shrinking, driven by technological innovations, changing social norms, and a collective desire to reach out and touch lives across vast distances. Incredibly, flimsy bits of cardstock sparked a global phenomenon that would revolutionize communication, art, and popular culture.

The story of the postcard’s rise to ubiquity is one of technological innovation meeting social evolution. The concept of sending messages on cards through the mail system wasn’t entirely new – the Austrian postal service had introduced Correspondenz-Karten in 1869, and other countries quickly followed suit. However, it was the convergence of several factors at the turn of the century that turned postcards from a curiosity into a global obsession.

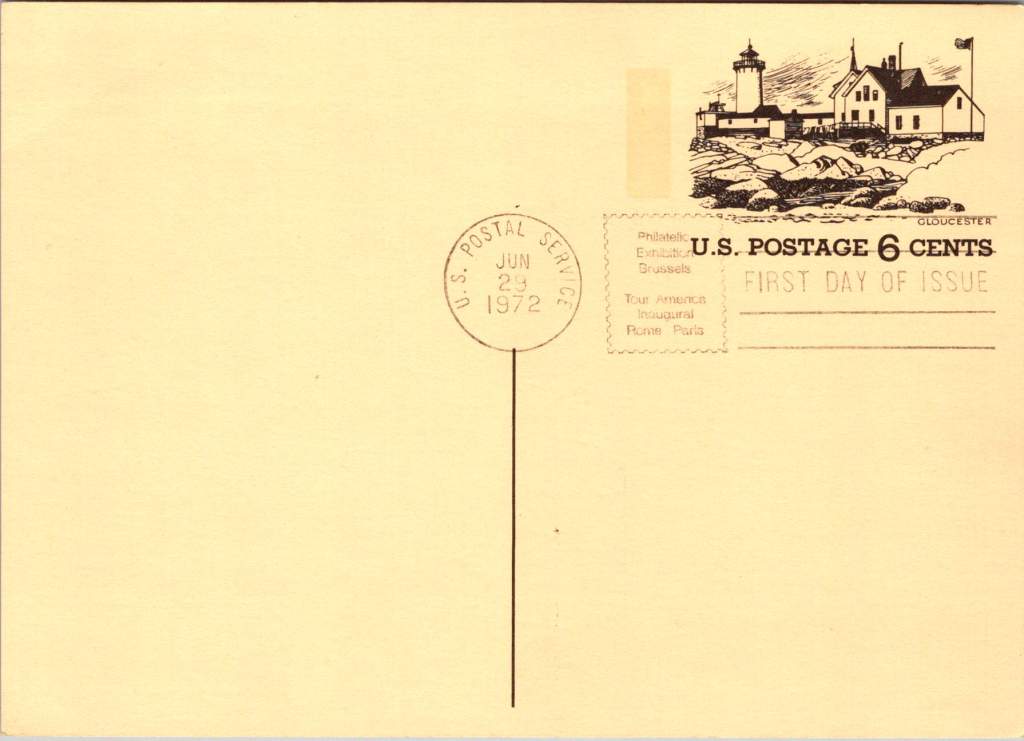

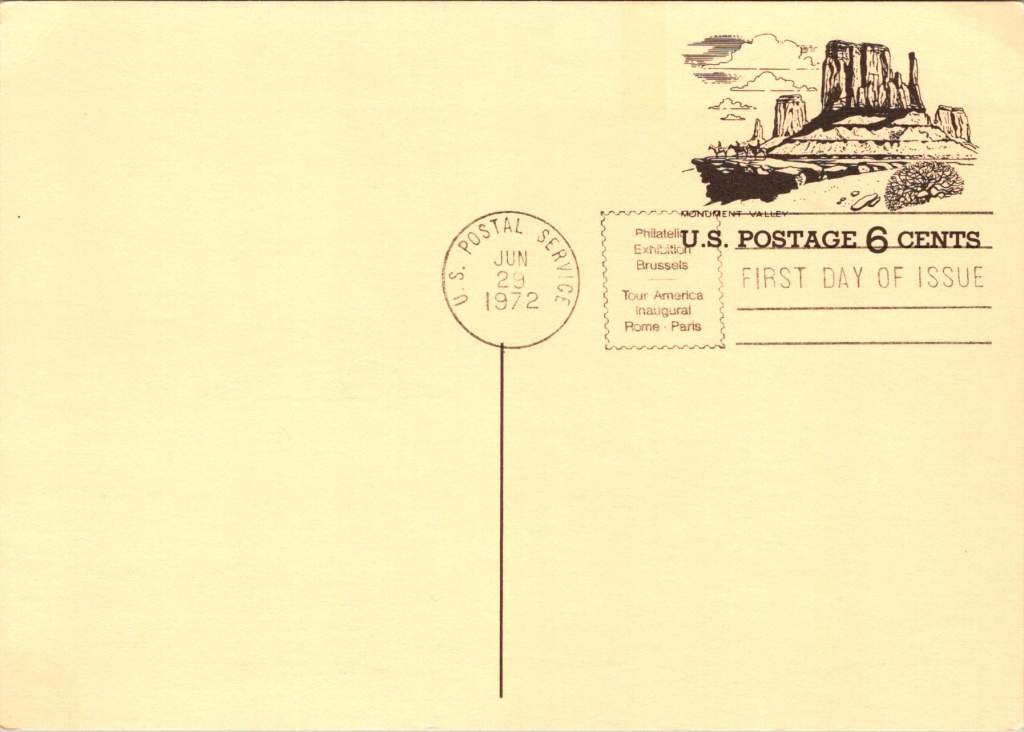

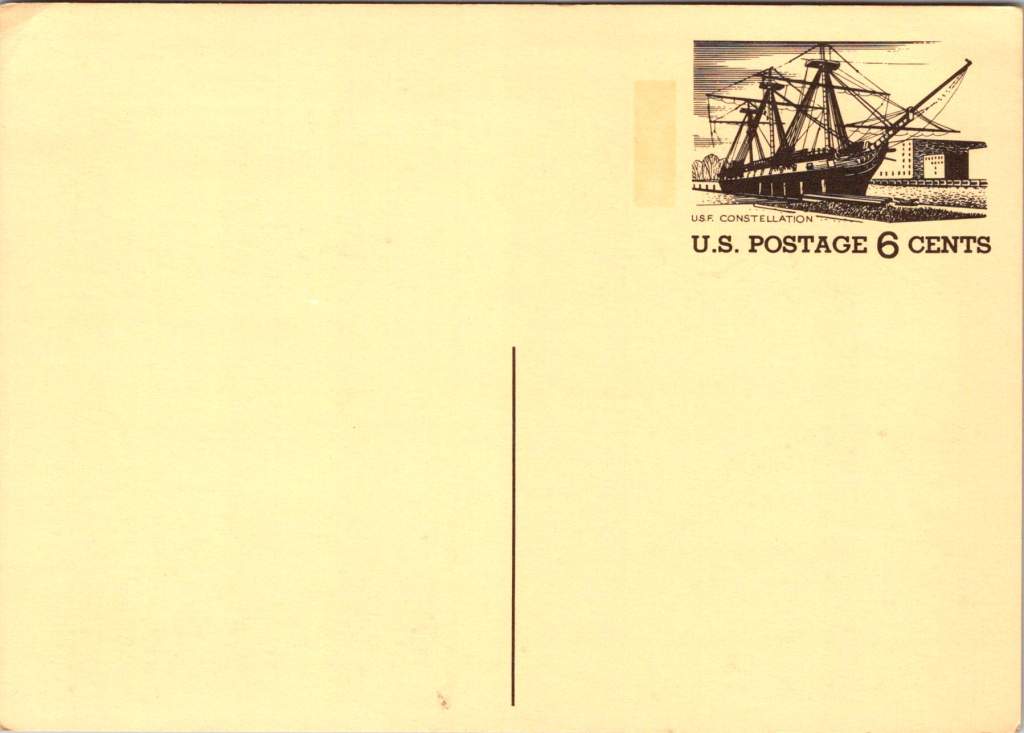

One key development was the improvement in printing technologies. The introduction of chromolithography in the late 19th century allowed for the mass production of colorful, high-quality images at relatively low cost. This was soon followed by photolithography and other techniques that could reproduce photographic images with stunning clarity. Suddenly, postcards could offer vivid glimpses of far-off places, famous personalities, or artistic creations, all at a price accessible to the average person.

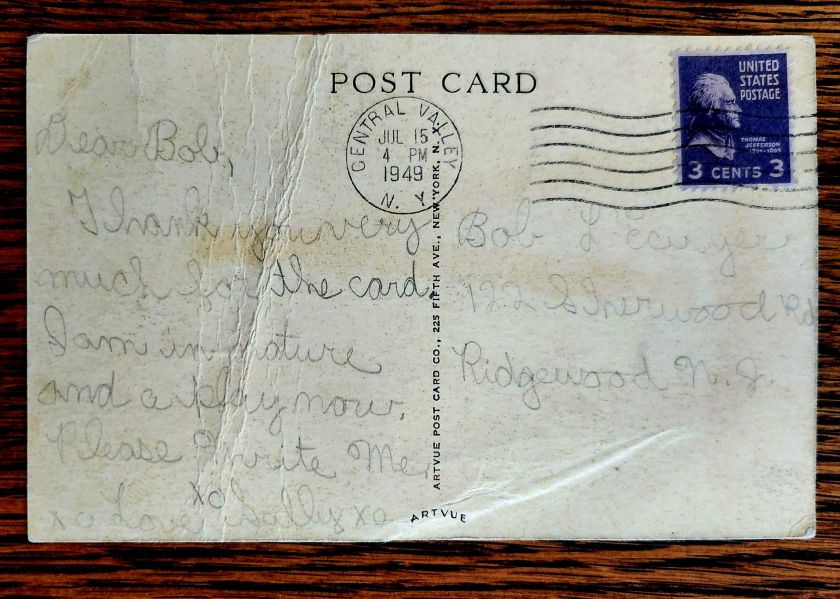

Another crucial factor was the standardization of postal regulations. The Universal Postal Union, established in 1874, helped to create a more uniform system for international mail. By 1902, they had standardized the format for postcards, dividing the back into two sections – one for the address and one for a message. This simple change dramatically increased the popularity of picture postcards, as senders could now include both an image and a personal message.

The final ingredient was a shift in social attitudes. As literacy rates rose and leisure time increased for many in the industrialized world, there was a growing appetite for new forms of communication and entertainment. Postcards fit the bill perfectly – they were affordable, visually appealing, and allowed for quick, casual correspondence in an increasingly fast-paced world.

Bamforth & Company

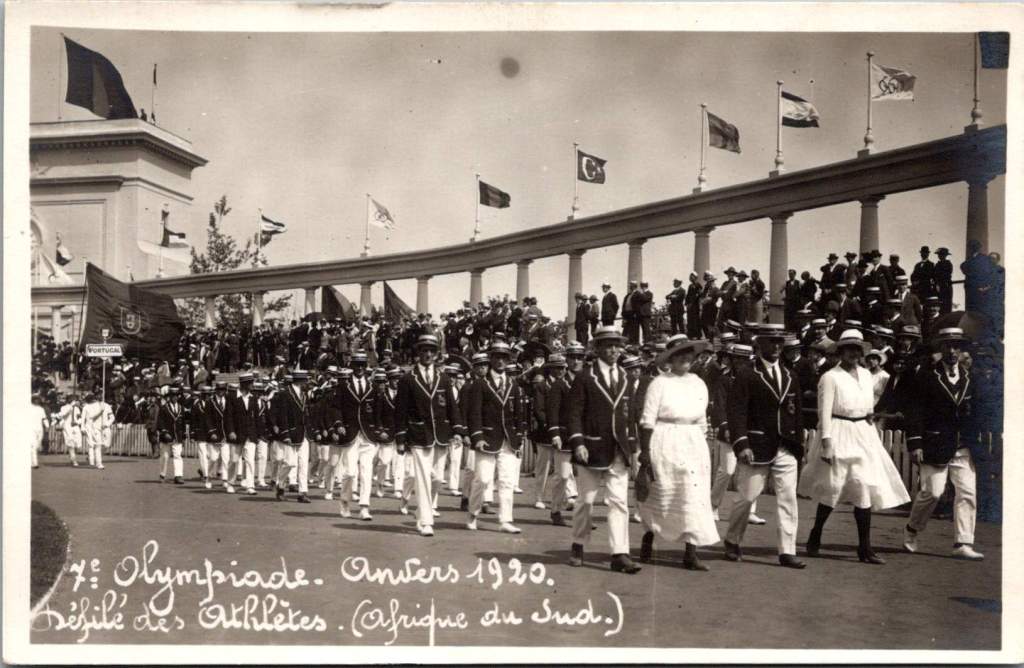

Our mystery postcard, with its subtle “B. & Co.” marking, leads us to one of the major players in the Golden Age of Postcards: Bamforth & Company. Founded by James Bamforth in Holmfirth, Yorkshire, in the 1870s, the company’s evolution mirrors the broader trajectory of the postcard industry.

Bamforth began as a portrait photography studio, capturing the likenesses of local Yorkshire residents. As technology advanced, the company expanded into the production of magic lantern slides – an early form of projected entertainment. This experience with visual media positioned Bamforth perfectly to capitalize on the postcard boom.

By the early 1900s, Bamforth & Co. had become one of the largest postcard publishers in the world. They were renowned for their high-quality printing and their diverse range of subjects. Sentimental scenes, comic situations, patriotic imagery, and holiday greetings were all part of their repertoire. The company often employed actors and models for their postcard images, creating idealized scenes that resonated with the public’s tastes and aspirations.

The postcard in our story – featuring a young woman in a white dress, holding a birthday greeting – is typical of Bamforth’s style. The sepia tone, the carefully posed subject, and the integration of a printed message all speak to the company’s expertise in creating appealing, marketable images.

But how did a postcard produced in a small Yorkshire town end up in the inventory of a postcard club in Topeka, Kansas? The answer lies in the remarkably global nature of the postcard trade during this era.

The Golden Age of Postcards

The Golden Age of Postcards coincided with a period of increasing globalization. Improvements in transportation, particularly the expansion of railway networks and steamship lines, facilitated the movement of goods on an unprecedented scale. Postcards, being lightweight and standardized, were ideal products for international trade.

Companies like Bamforth & Co. didn’t limit themselves to local or even national markets. They established distribution networks that spanned continents, often working with agents or partnering with local publishers in different countries. In the United States, for example, many European postcard designs were printed under license by American companies, while others were imported directly.

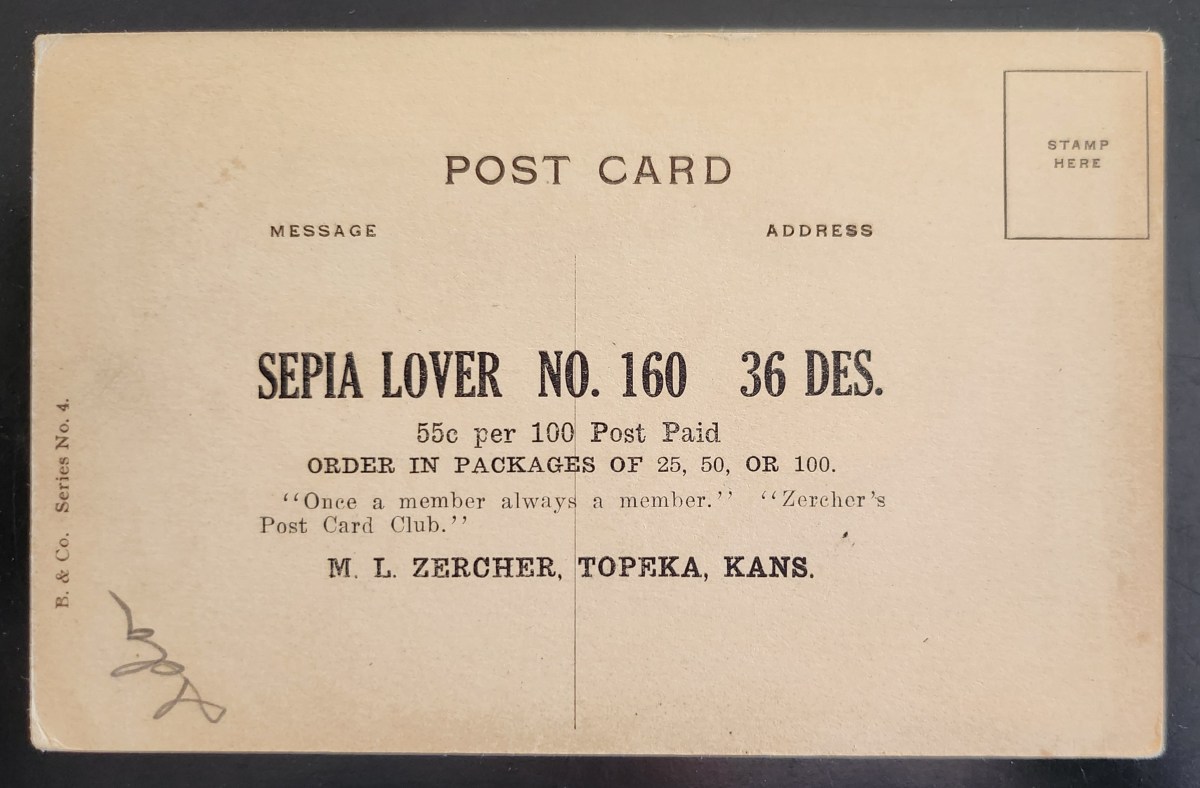

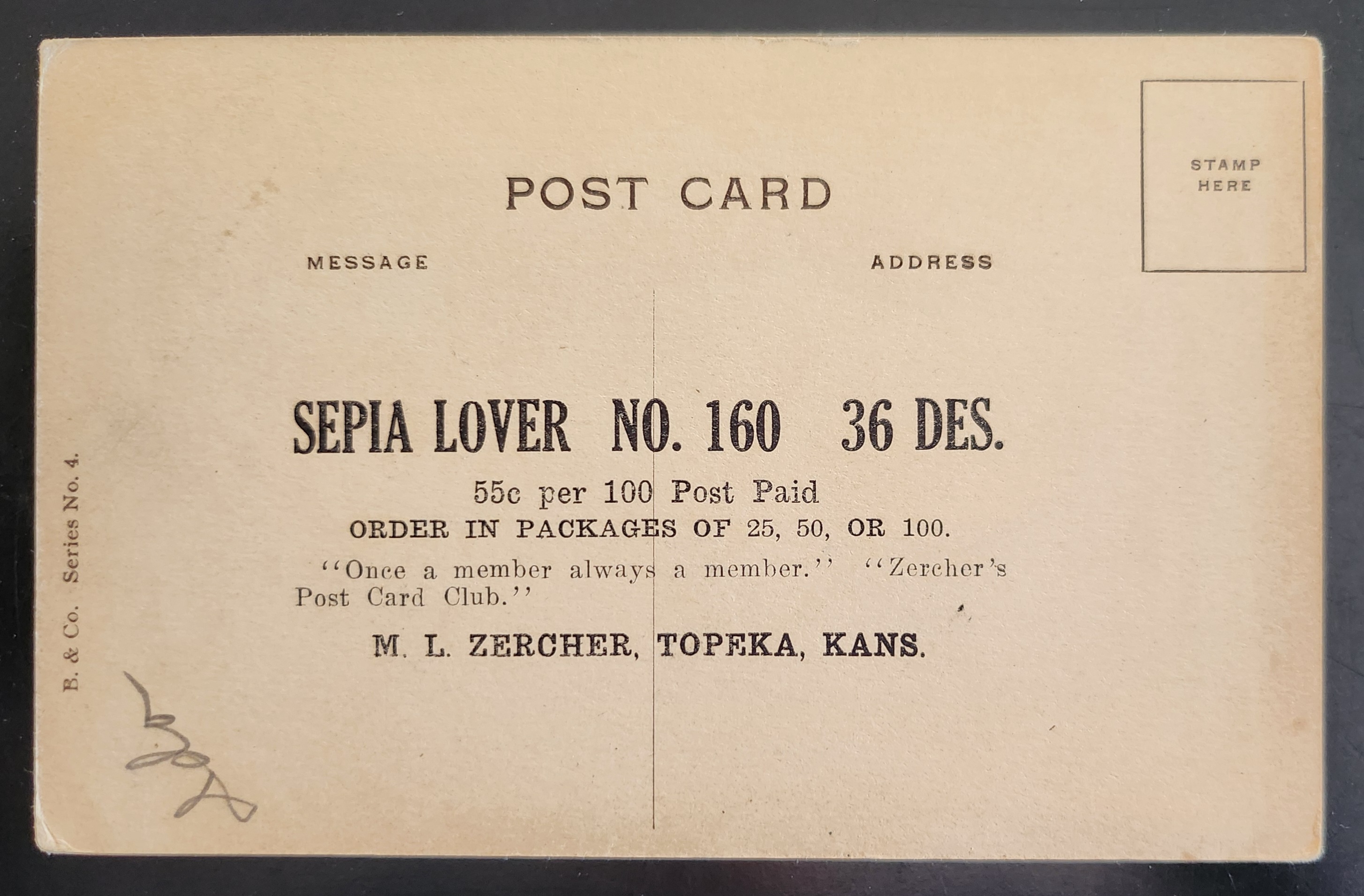

Postcard Clubs

The explosion in postcard popularity led to the emergence of specialized businesses catering to collectors and enthusiasts. Postcard clubs, like Zercher’s Post Card Club in Topeka, played a crucial role in this ecosystem. These clubs served multiple functions: They acted as distributors, buying postcards in bulk from publishers and reselling them to members. They facilitated exchanges between collectors, allowing members to trade cards and expand their collections. They created a sense of community among postcard enthusiasts, often publishing newsletters or directories of members.

M.L. Zercher’s operation in Topeka was just one of many such clubs that sprang up across the United States and around the world. The back of our mystery postcard gives us some insight into how these clubs operated. It advertises postcards for sale at “55c per 100 Post Paid” and encourages customers to “ORDER IN PACKAGES OF 25, 50, OR 100.” This bulk pricing model allowed collectors to quickly build their collections or stock up on cards to send.

The slogan “Once a member always a member” suggests that Zercher’s club operated on a subscription or membership basis, likely offering special deals or access to rare cards as incentives for joining. The fact that a British-made card was part of their inventory demonstrates the truly international nature of the postcard trade. Clubs like Zercher’s would source cards from a variety of publishers, both domestic and foreign, to offer their members a diverse selection.

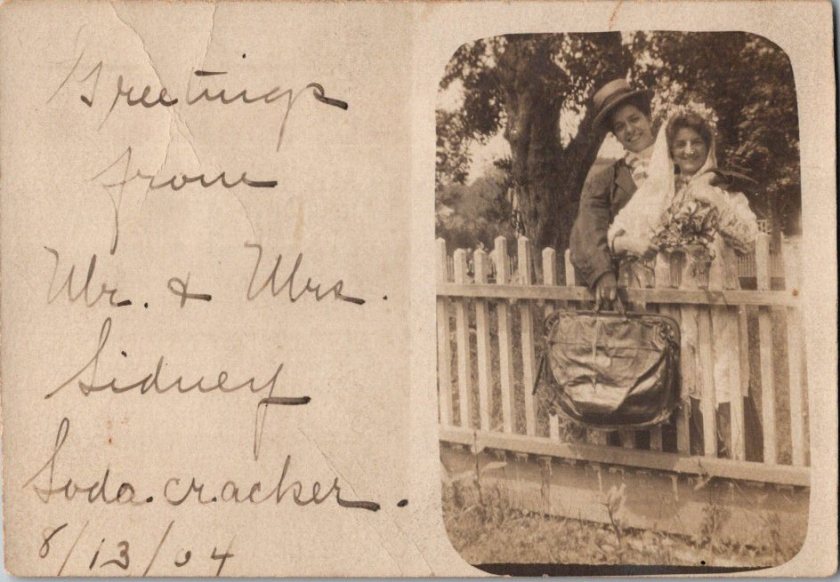

To truly understand the significance of our mystery postcard and the era it represents, we need to consider the broader cultural impact of the postcard craze. In many ways, postcards in the early 20th century served a similar function to social media in our own time – they were a quick, visual means of sharing experiences, expressing sentiments, and staying connected.

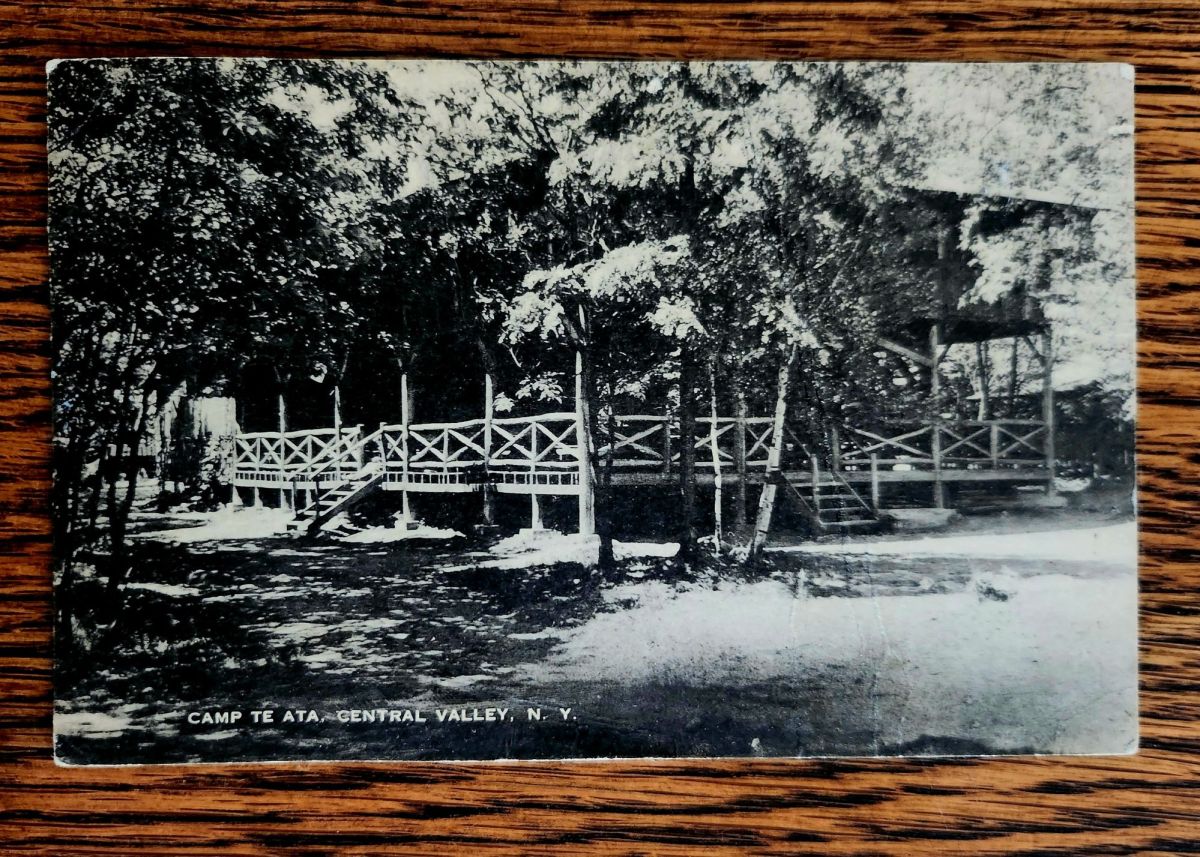

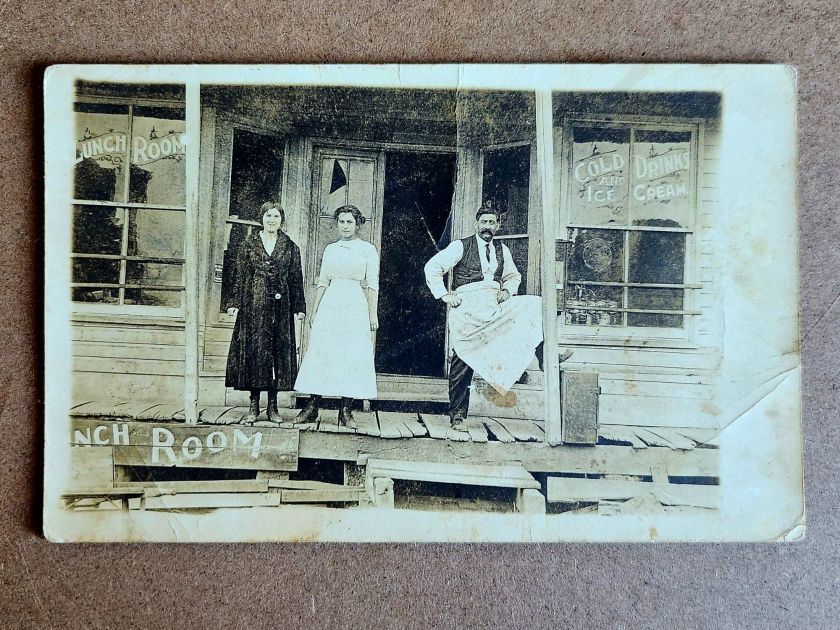

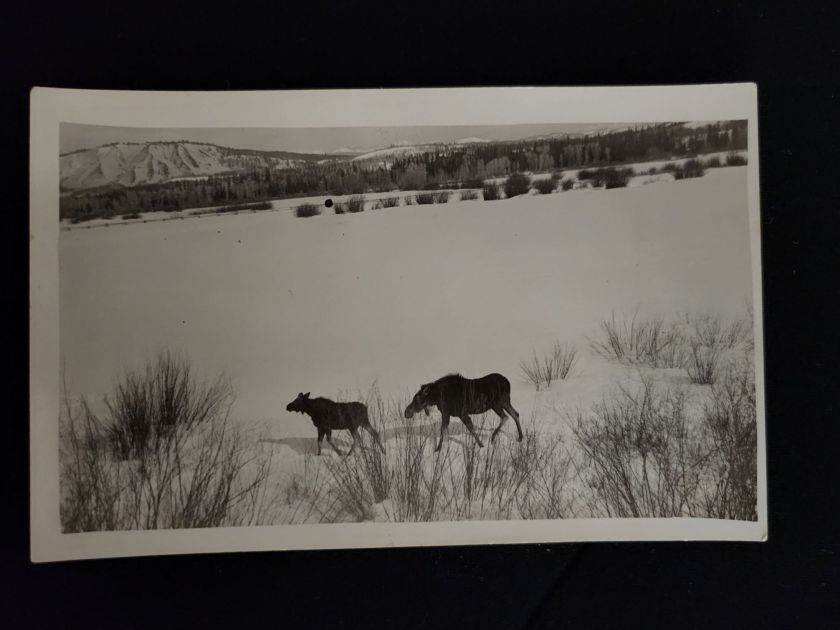

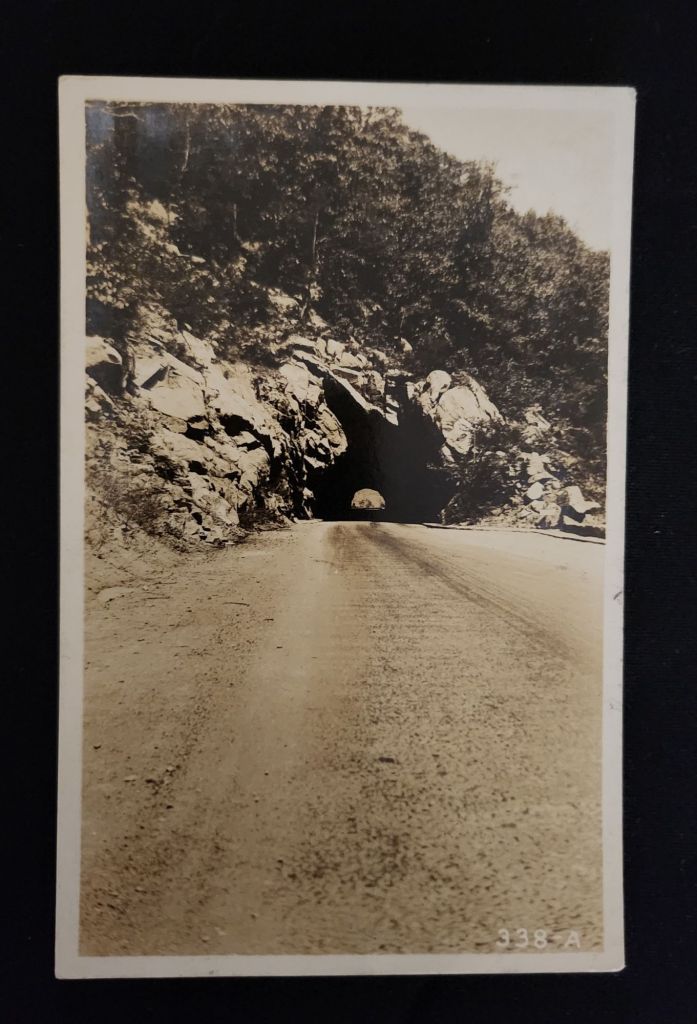

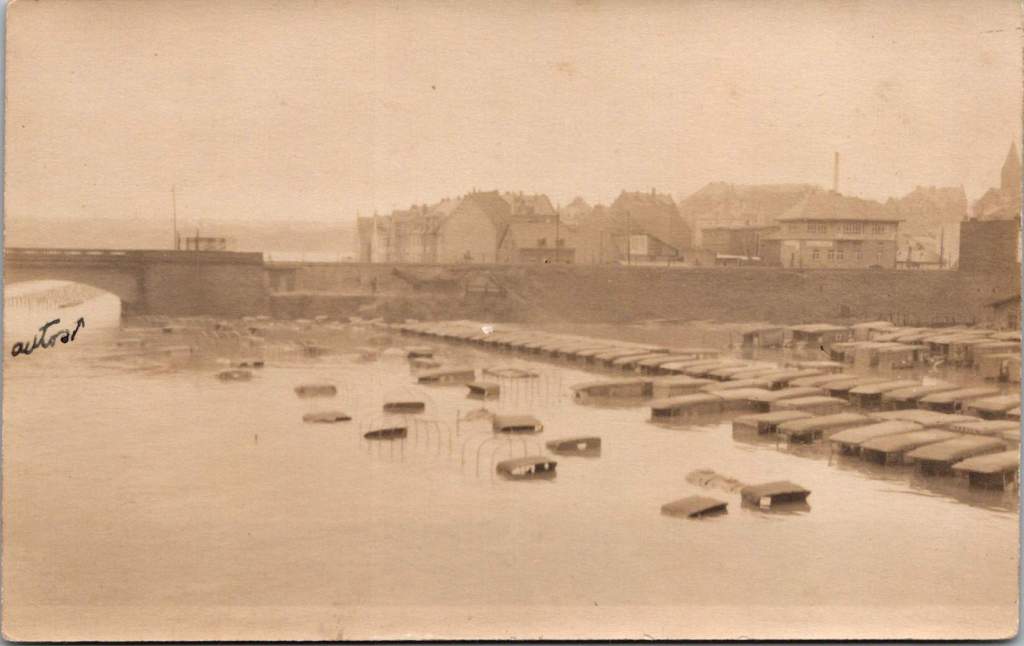

Postcards became a way for people to “collect” the world. Travel postcards allowed those who couldn’t afford to venture far from home to glimpse exotic locations and different ways of life. Topographical cards documented the changing face of cities and towns, preserving images of streets, buildings, and landscapes that in many cases have long since disappeared.

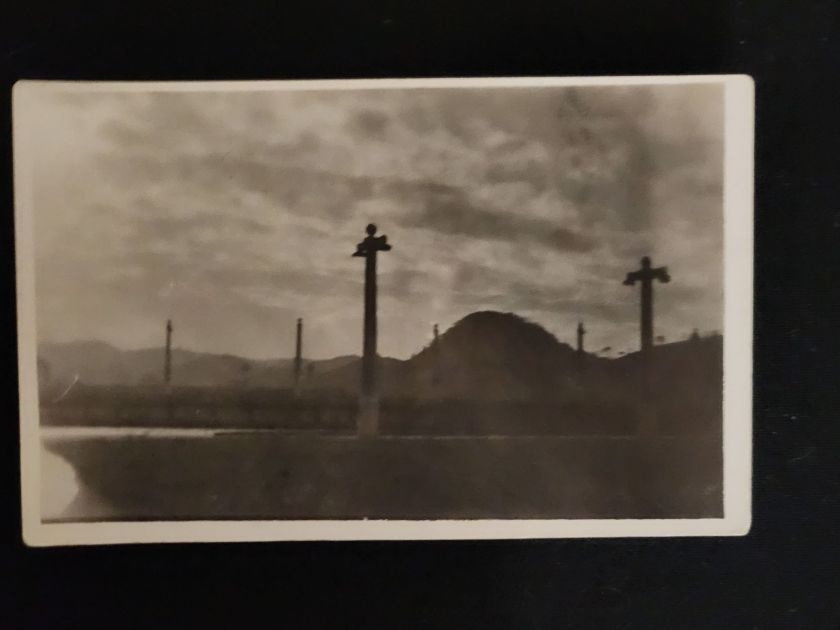

The subject matter of postcards was incredibly diverse, reflecting and shaping popular culture of the time. In addition to scenic views and greeting cards, publishers produced postcards featuring current events and news stories, popular entertainers and public figures, humorous cartoons and jokes, art reproductions, advertisements for products and services, and political messages and propaganda.

Postcards were also a medium for artistic expression. Many renowned artists of the period, including Alphonse Mucha and Raphael Kirchner, designed postcards. The Art Nouveau and later Art Deco movements found in postcards a perfect vehicle for reaching a mass audience.

The act of sending and collecting postcards became a hobby in itself, known as deltiology. Postcard albums were a common feature in many homes, filled with cards received from friends and family or purchased as souvenirs. The craze reached such heights that some contemporary observers worried about its effects, particularly on young people. A 1906 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch decried the “Postal Card Habit” as a “Decidedly Pernicious Fad,” concerned that it was discouraging more substantive forms of written communication.

Returning to our specific postcard, we’re left with an intriguing question: Who is the young woman in the image? The nature of postcard production at the time means that her identity is likely lost to history, but we can make some educated guesses about her role.

Bamforth & Co., like many postcard publishers, often employed local actors or models for their images. The woman in the photograph, with her carefully arranged hair and white dress, was likely chosen to embody an idealized image of youthful beauty and innocence. Her pose, holding the birthday greeting, is clearly staged for the camera.

It’s worth noting that while the main image and the text at the bottom of the card (“Accept from me with hearty cheer / The honest wish that’s printed here”) were likely printed together using a process like collotype, the specific birthday message appears to have been added later through letterpress printing. This was a common practice, allowing publishers to use the same base image for multiple occasions by simply changing the text.

The anonymity of the subject is, in many ways, part of the postcard’s appeal. Senders could project their own meanings onto the image, using it to convey personal messages to friends and loved ones. The young woman becomes a stand-in, a vessel for the sender’s sentiments rather than a specific individual.

Like many cultural phenomena, the postcard craze couldn’t sustain its intense popularity indefinitely. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked the beginning of the end for the Golden Age of Postcards. While postcards remained popular during the war years, with many soldiers using them to communicate with loved ones back home, several factors contributed to their decline.

Wartime paper shortages and increased postal rates made postcards more expensive to produce and send. The disruption of international trade networks made it harder for publishers to distribute cards globally. Changing tastes and new forms of mass media, particularly radio and later television, began to compete for people’s attention. The increasing affordability and popularity of personal cameras meant that people could create their own photographic mementos rather than relying on commercial postcards.

In the post-war years, the postcard industry consolidated. Many smaller publishers and clubs, like Zercher’s in Topeka, likely went out of business or were absorbed by larger companies. Bamforth & Co., our postcard’s originator, managed to adapt and survive, shifting its focus more towards comic postcards in the latter half of the 20th century before finally ceasing operations in 2000.

While the Golden Age of Postcards may have ended, its impact continues to be felt in various ways. Postcards from this era serve as invaluable historical documents, offering glimpses into the social, cultural, and physical landscapes of the early 20th century. Historians and archaeologists often use postcards as sources in their research.

The aesthetic styles popularized in postcards, particularly Art Nouveau and Art Deco designs, continue to influence graphic design and illustration. Deltiology remains a popular hobby, with collectors specializing in particular themes, publishers, or geographical areas. Rare postcards from the Golden Age can command high prices at auctions.

While not reaching the heights of the Golden Age, postcards have seen periodic resurgences in popularity. The rise of sites like Postcrossing, which facilitates international postcard exchanges, shows that the appeal of sending and receiving physical cards endures in the digital age. The idea of the picture postcard as a souvenir or greeting has become deeply embedded in our cultural consciousness, even as actual postcard usage has declined.

Our journey, which began with a single postcard – a young woman holding a birthday greeting, produced in England but found in Kansas – has taken us through a remarkable period in cultural and communication history. The Golden Age of Postcards was more than just a craze or a fad; it was a global phenomenon that changed how people interacted with the world around them and with each other.

This era saw the convergence of technological innovation, social change, and artistic expression, resulting in a medium that was simultaneously personal and mass-produced, local and global. The postcard became a canvas for human creativity and connection, allowing people to share snippets of their lives and their world in ways that had never before been possible.

As we look at our mystery postcard today, the young woman’s identity may remain unknown, but her image speaks volumes about the time in which she lived. It tells us of a world that was rapidly shrinking, where an image created in a small English town could find its way to the American Midwest. It speaks of changing social norms, of new ideas about communication and personal expression. And it reminds us of the enduring human desire to reach out, to share, to connect – a desire that transcends time and technology.

In an age of instant digital communication, where images and messages circle the globe in seconds, there’s something poignant about this physical artifact of a slower, more deliberate form of correspondence. The postcard from Zercher’s club, with its sepia-toned charm, invites us to pause and reflect on how we communicate today, and what might be gained or lost in the dizzying pace of technological change.

The Golden Age of Postcards may be long past, but its legacy lives on – in the millions of cards preserved in albums and archives, in the visual language it helped to create, and in the ways it shaped our understanding of global connection. As we send our tweets and instant messages, share our digital photos, and connect across vast distances in the blink of an eye, we are, in many ways, the inheritors of a revolution that began with a simple piece of cardboard and a penny stamp. The world of Bamforth & Co. and Zercher’s Post Card Club may seem distant, but its echoes continue to shape our own.