Nina found Mrs. Hanabusa in the common room sorting groceries into cloth bags. The postcard was still in Nina’s hand—a Navajo textile in geometric patterns, black and white against red wool.

“Let me help,” Nina said, taking two bags.

Mrs. Hanabusa glanced at the card. “From your friend? The one who went to Taipei?”

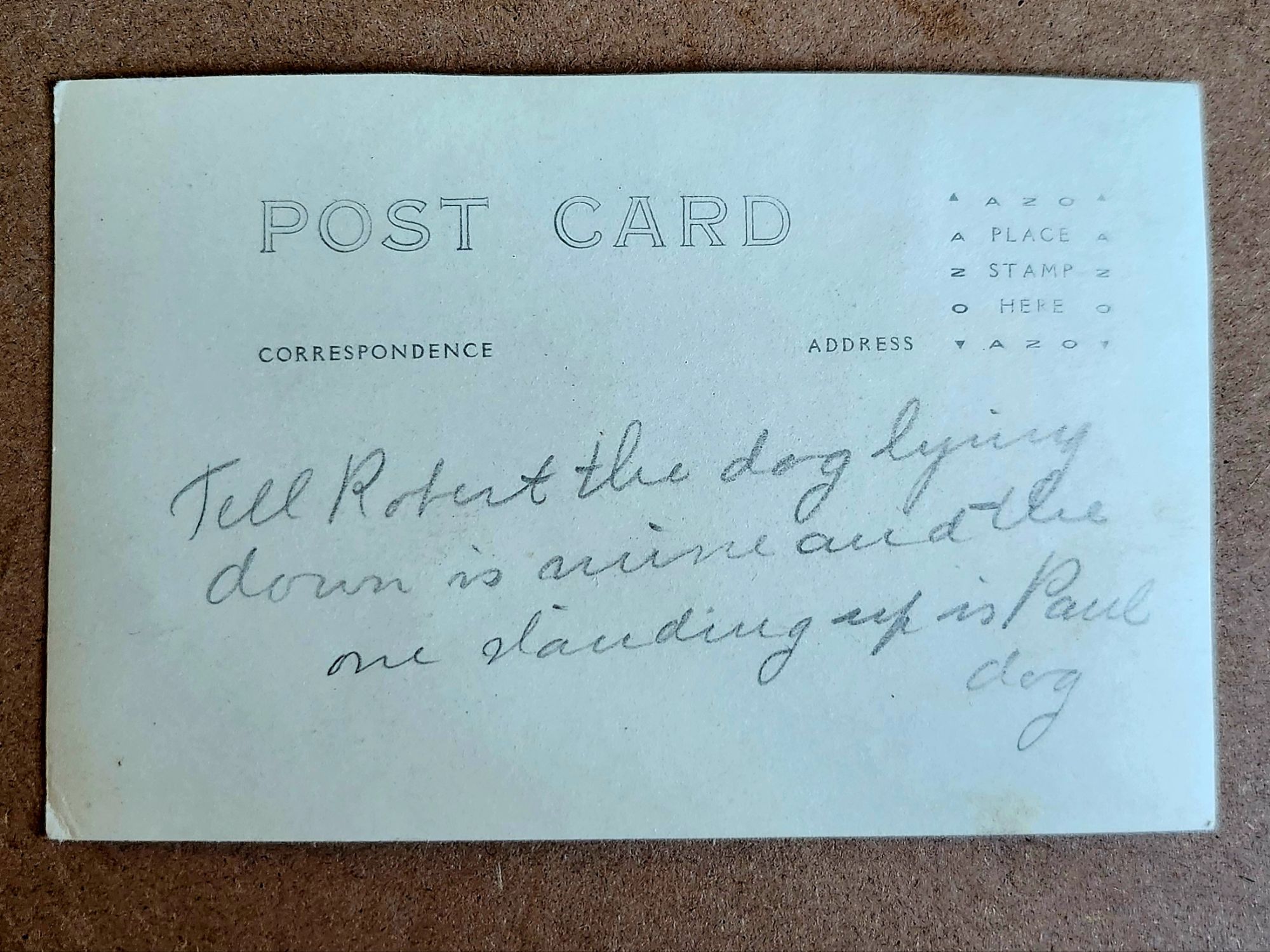

“She just arrived.” Nina turned the card over.

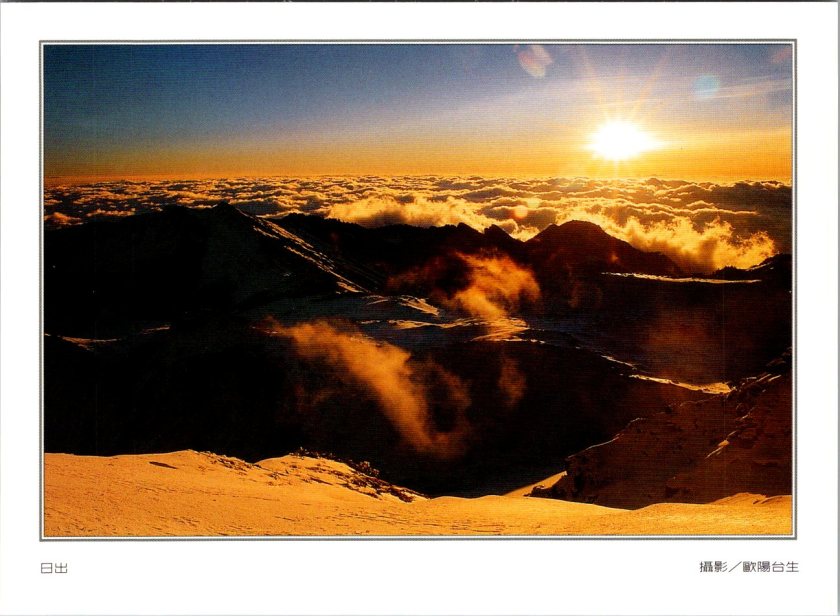

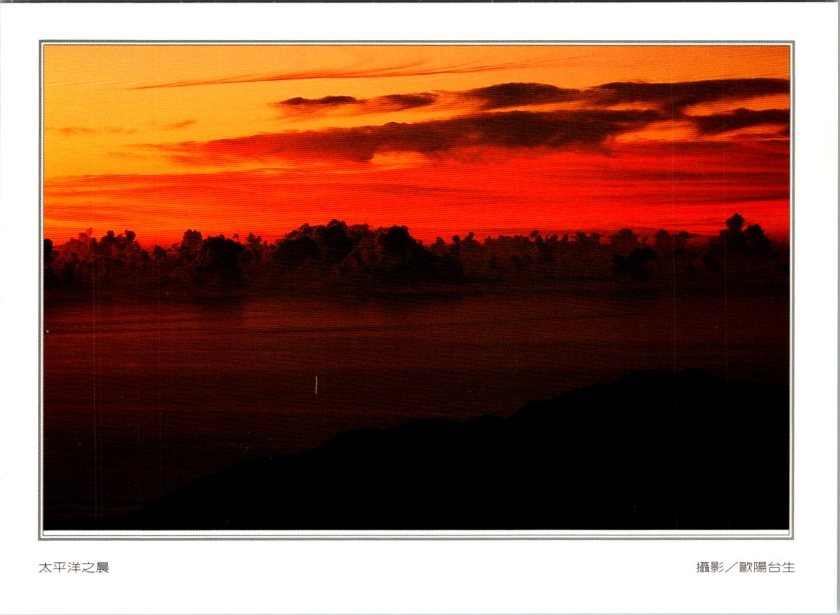

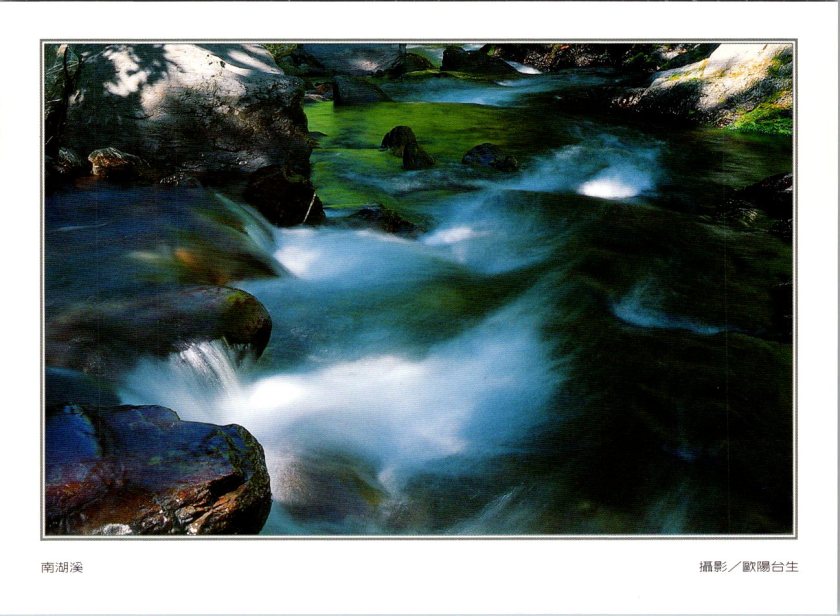

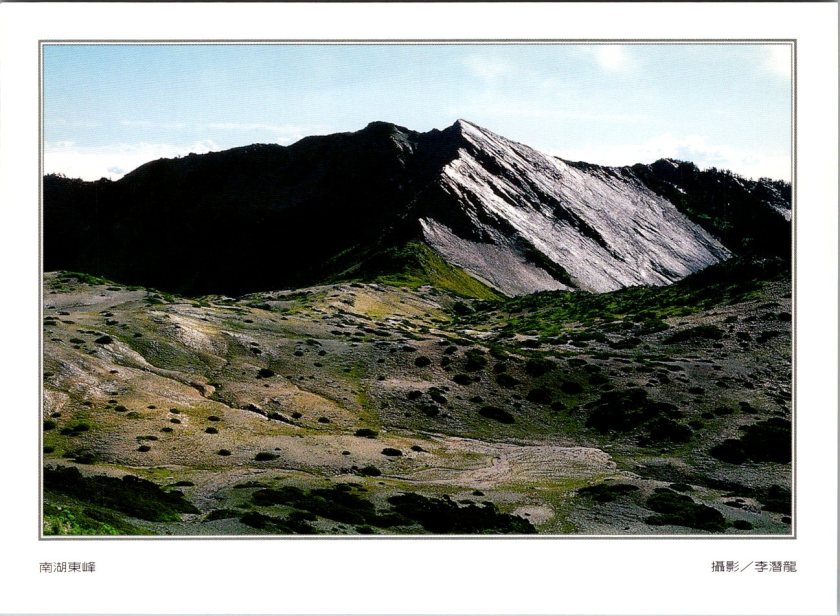

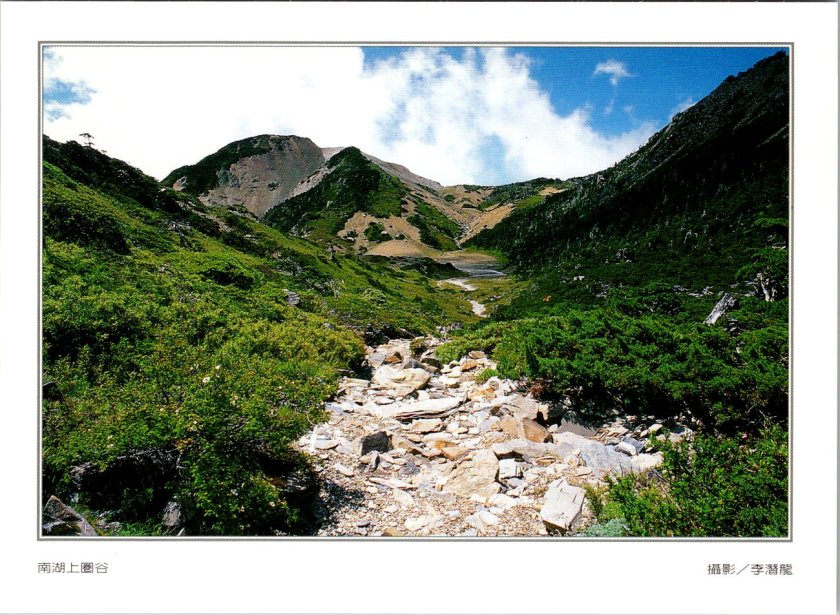

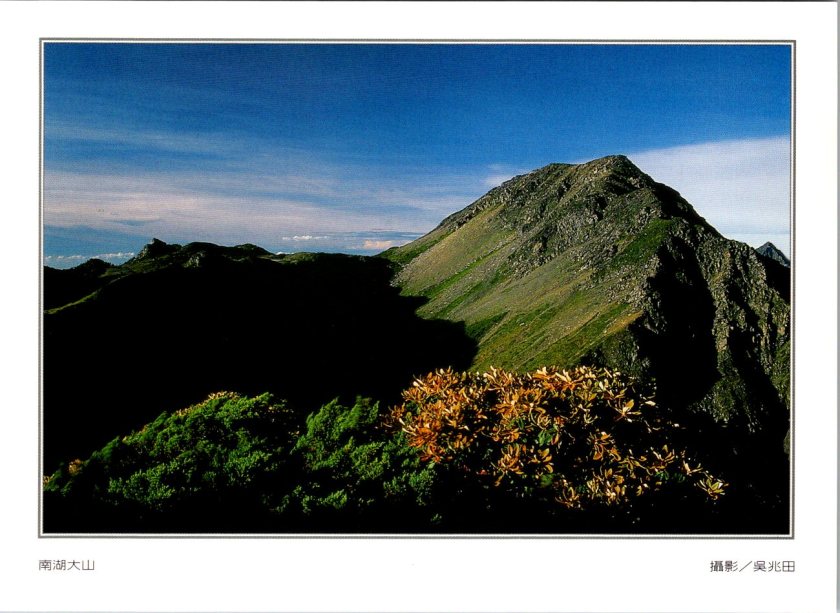

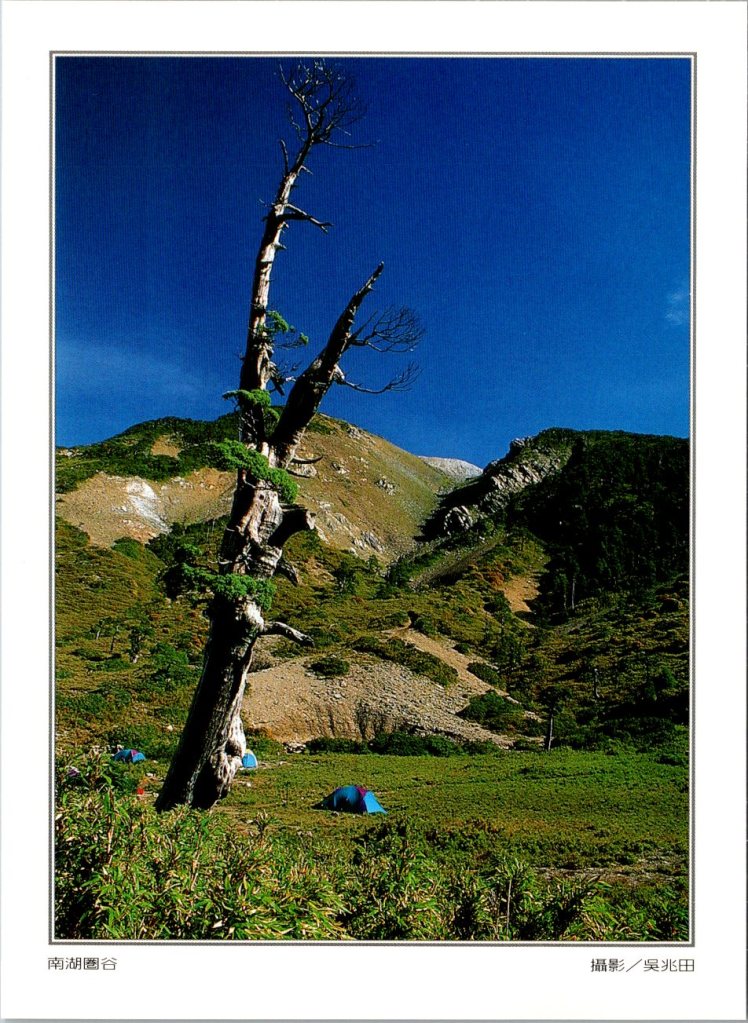

Made it. Everything moves faster here. First night was a photo exhibit on Mt Nunhu. Already miss the slow mornings. —N

Funny, Nina had received Nora’s text with images from the show that night, long before the postcard arrived in her mailbox here in Tucson.

They walked to Mrs. Hanabusa’s room. Nina set the bags on the small counter. Mrs. H studied the postcard, her finger tracing the pattern.

“My grandparents had one like this. Hung in their house on the flower farm.” She paused. “My grandmother found it at a trading post in the twenties. She said the geometry reminded her of Japanese family crests. Clean lines. She hung it in the room where they did arrangements.”

Mrs. H’s voice stayed quiet, remembering. “After the war, when we came back from the camps, the farm was gone. But a neighbor had saved some things. The rug was one of them. Grandmother cried when she saw it. I was small, maybe seven. I didn’t understand then what it meant to get something back.”

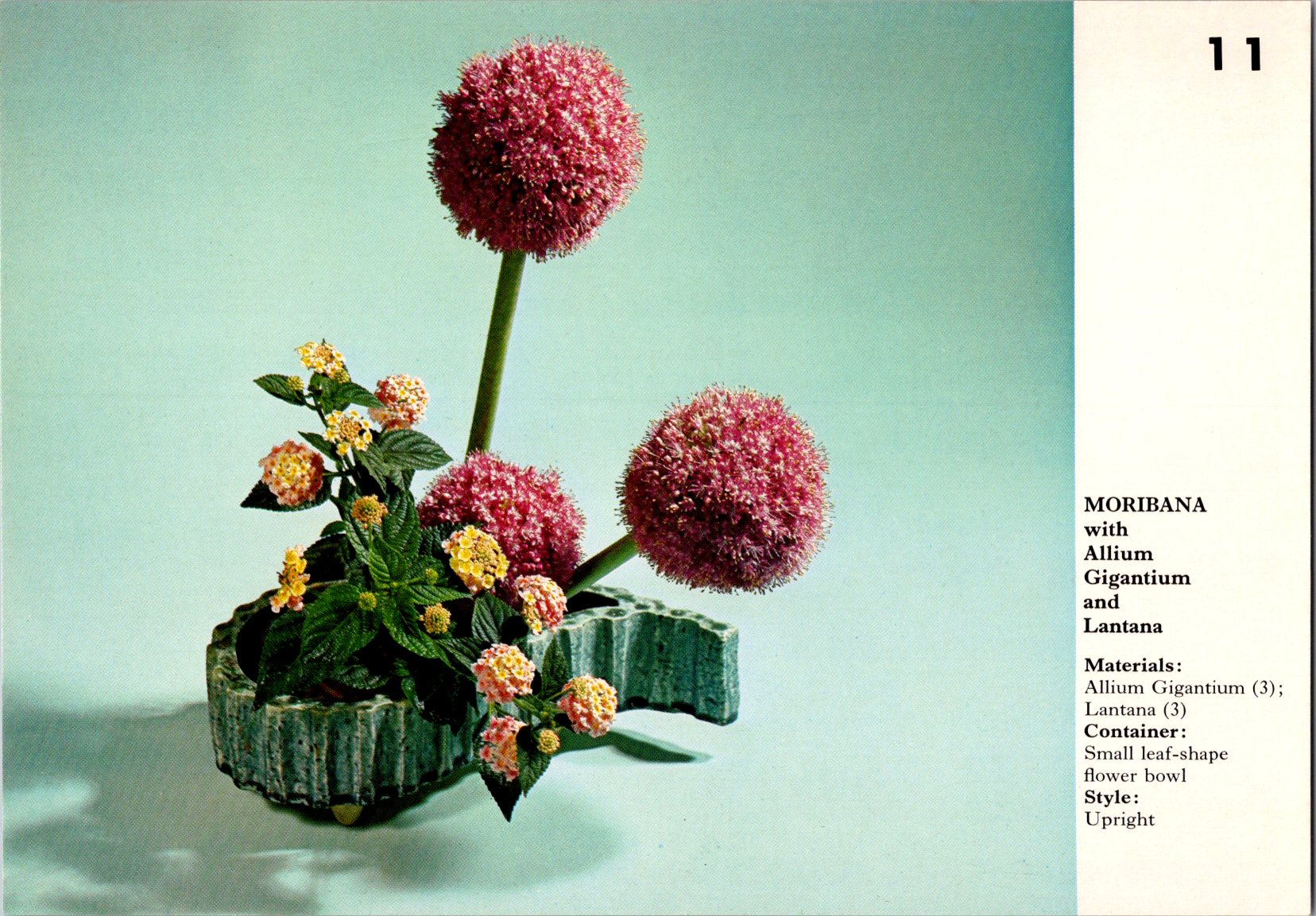

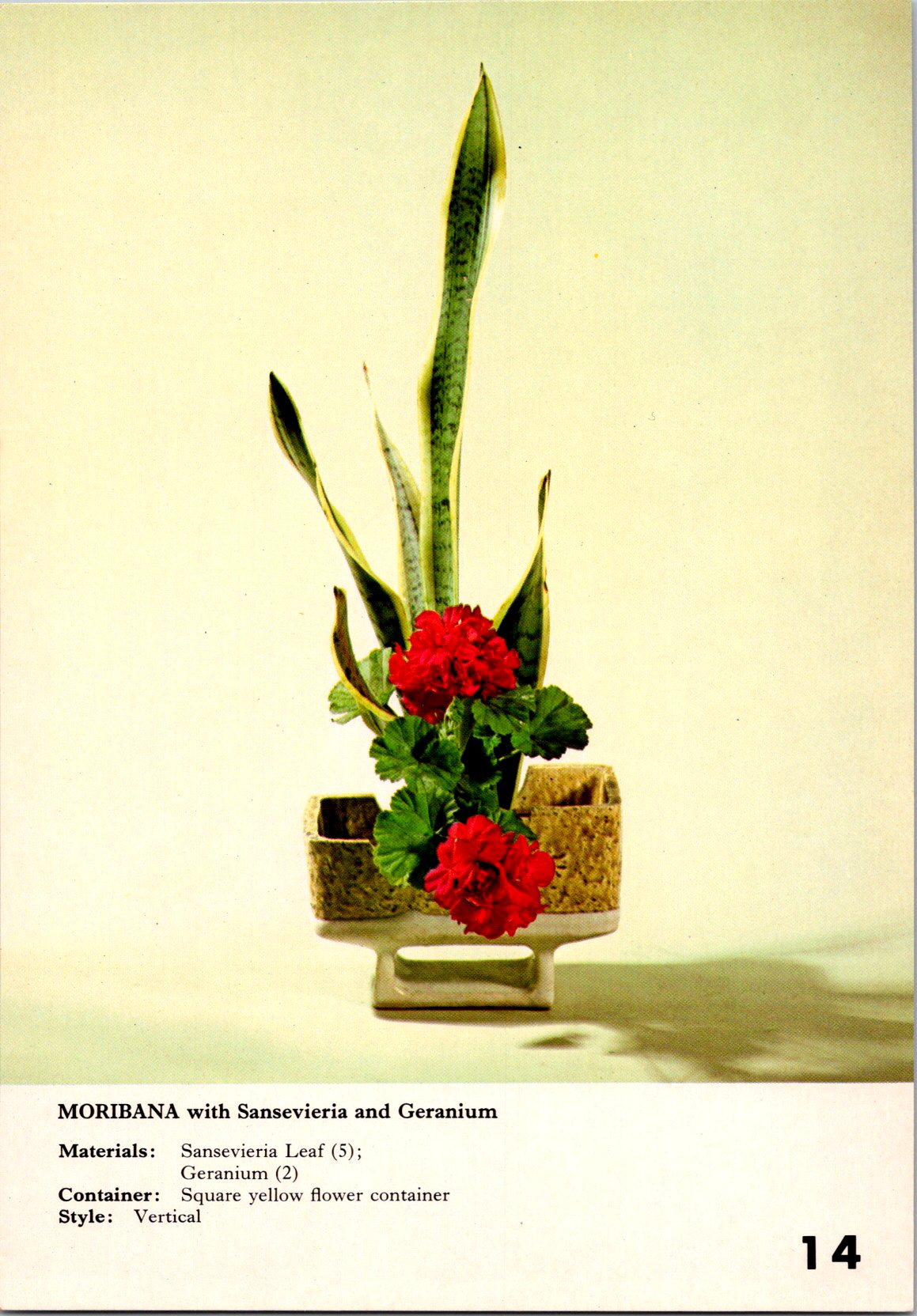

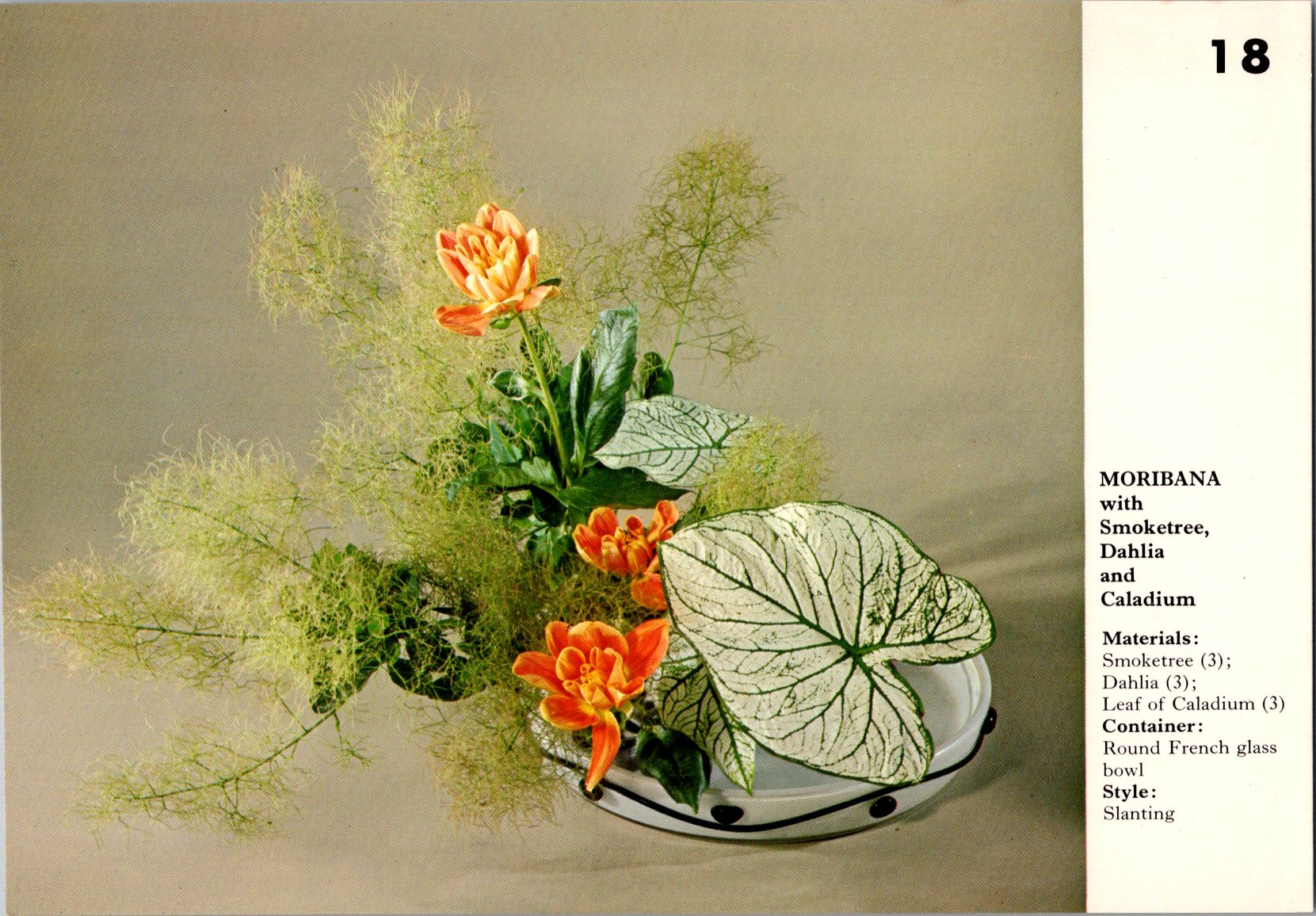

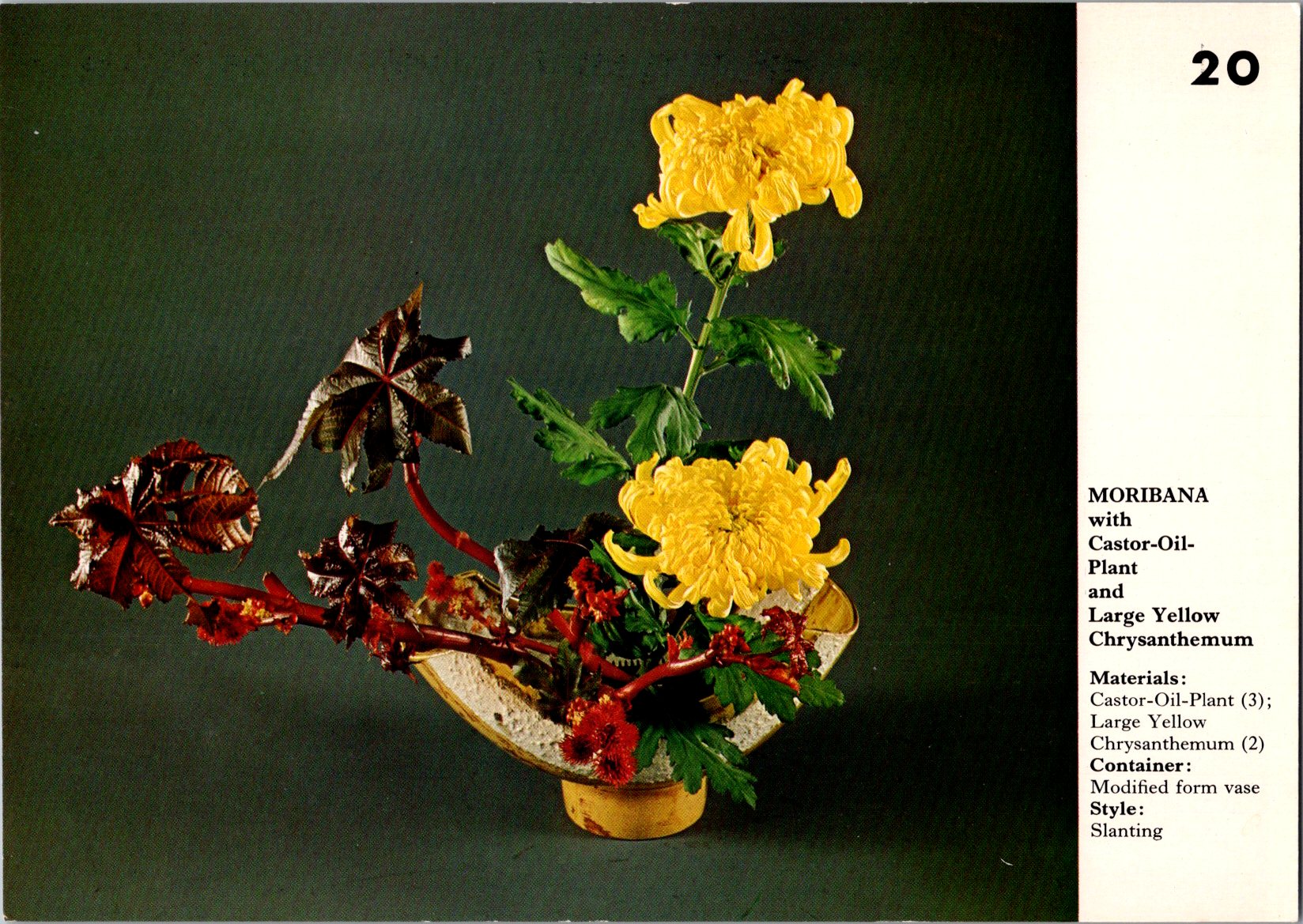

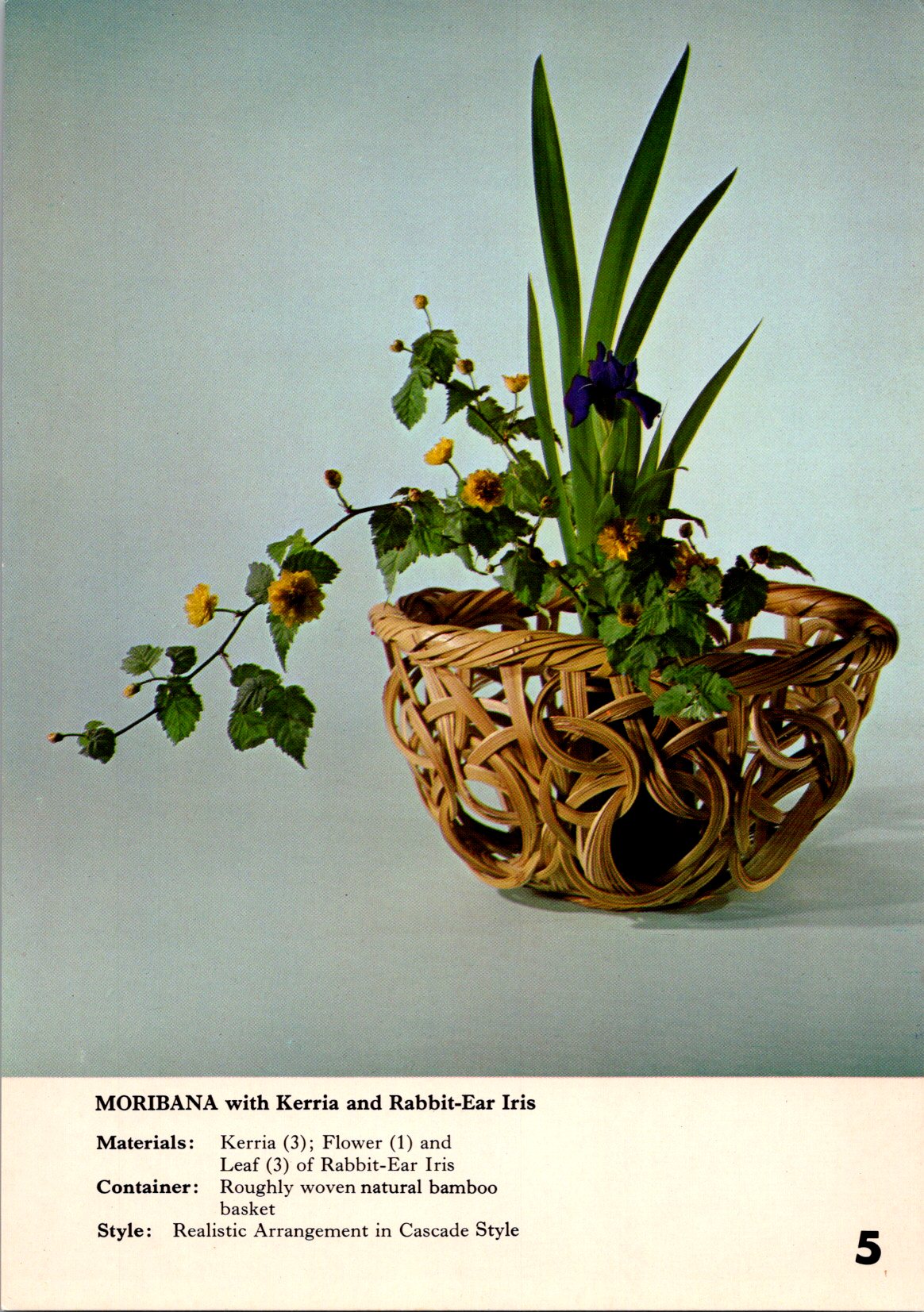

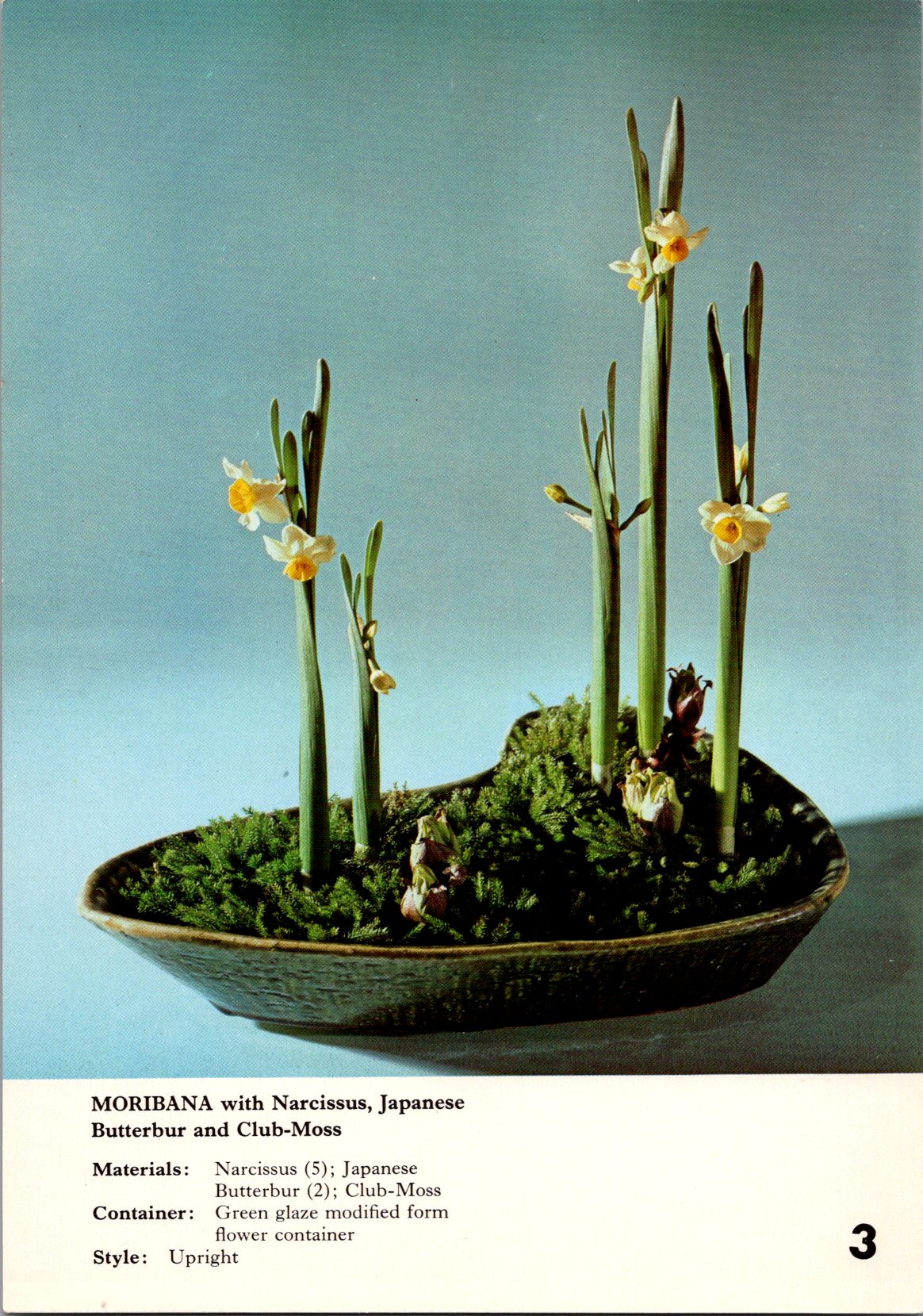

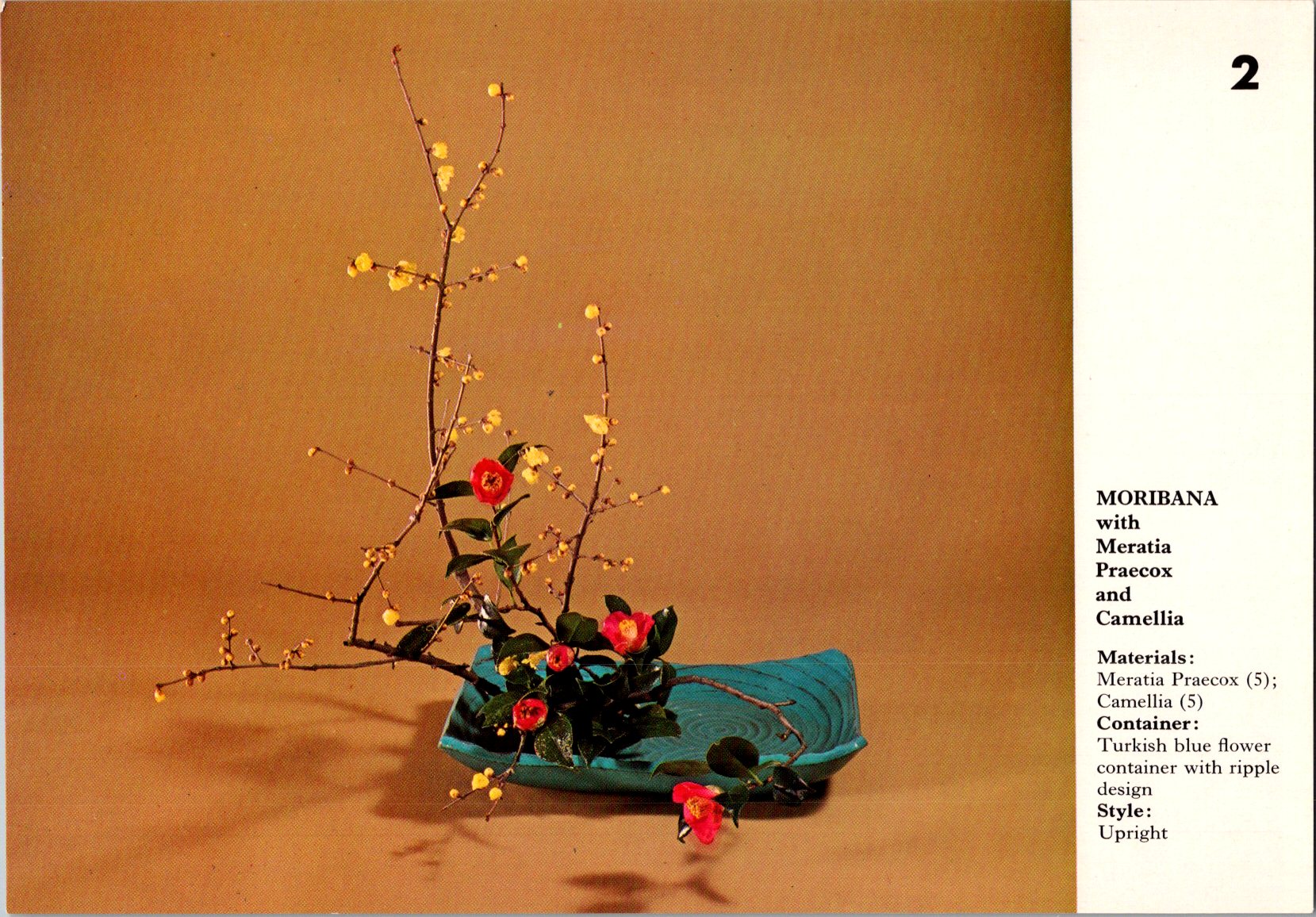

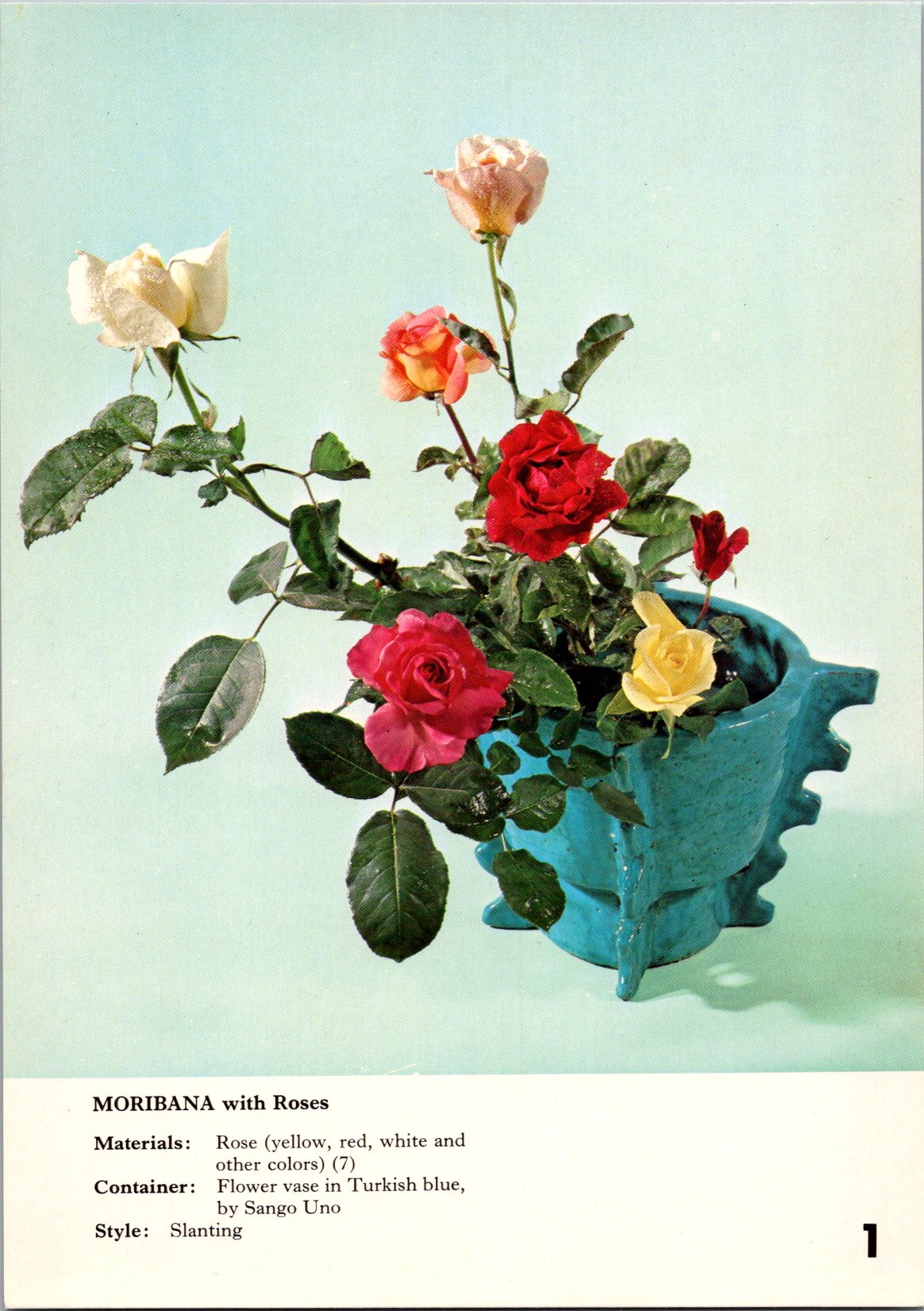

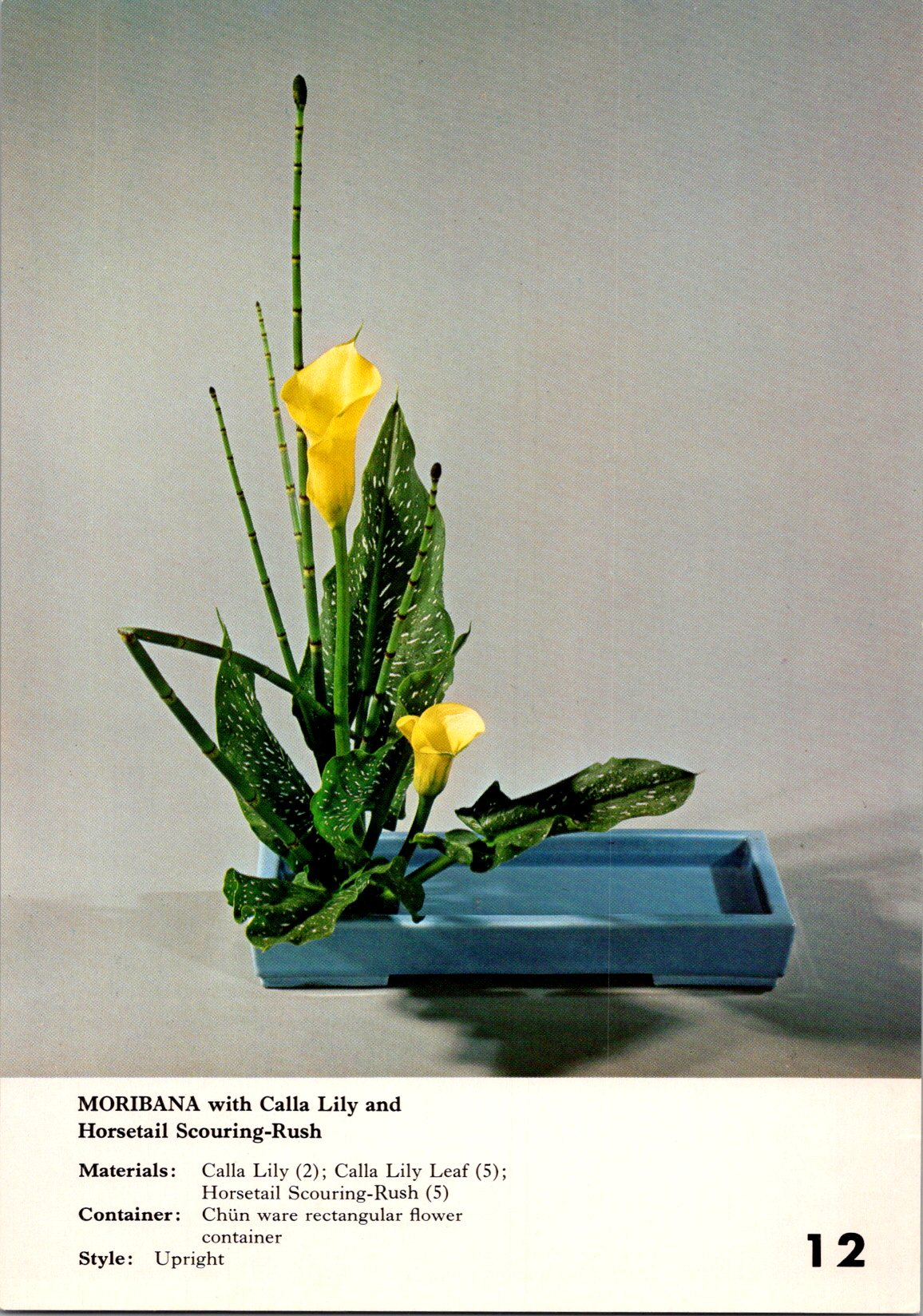

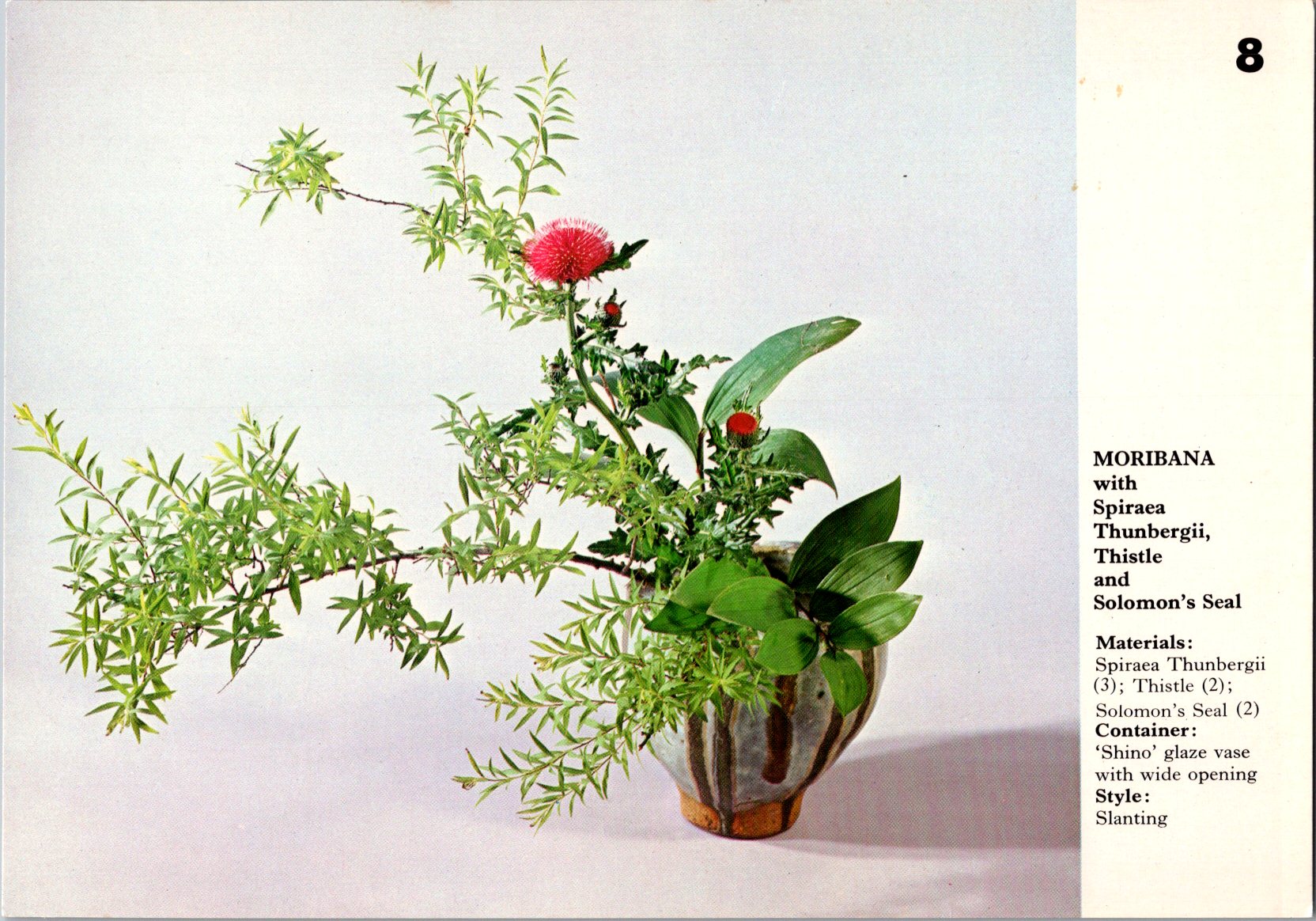

She opened a drawer, pulled out a small wooden box. Inside lay perhaps a dozen postcards, all showing Ikebana arrangements with low, horizontal compositions in shallow containers. Pink and red cosmos rising from a white porcelain vase. Allium gigantium’s perfect spheres balanced with small lantana blooms. A giant monstera leaf with a canna lily and a white chrysanthemum.

Mrs. Hanabusa handed Nina the stack of cards. She flipped through slowly, admiring each floral design.

“My sister sent these from Osaka. Our grandmother taught the traditional way. These are more like her arrangements, traditional but made new.”

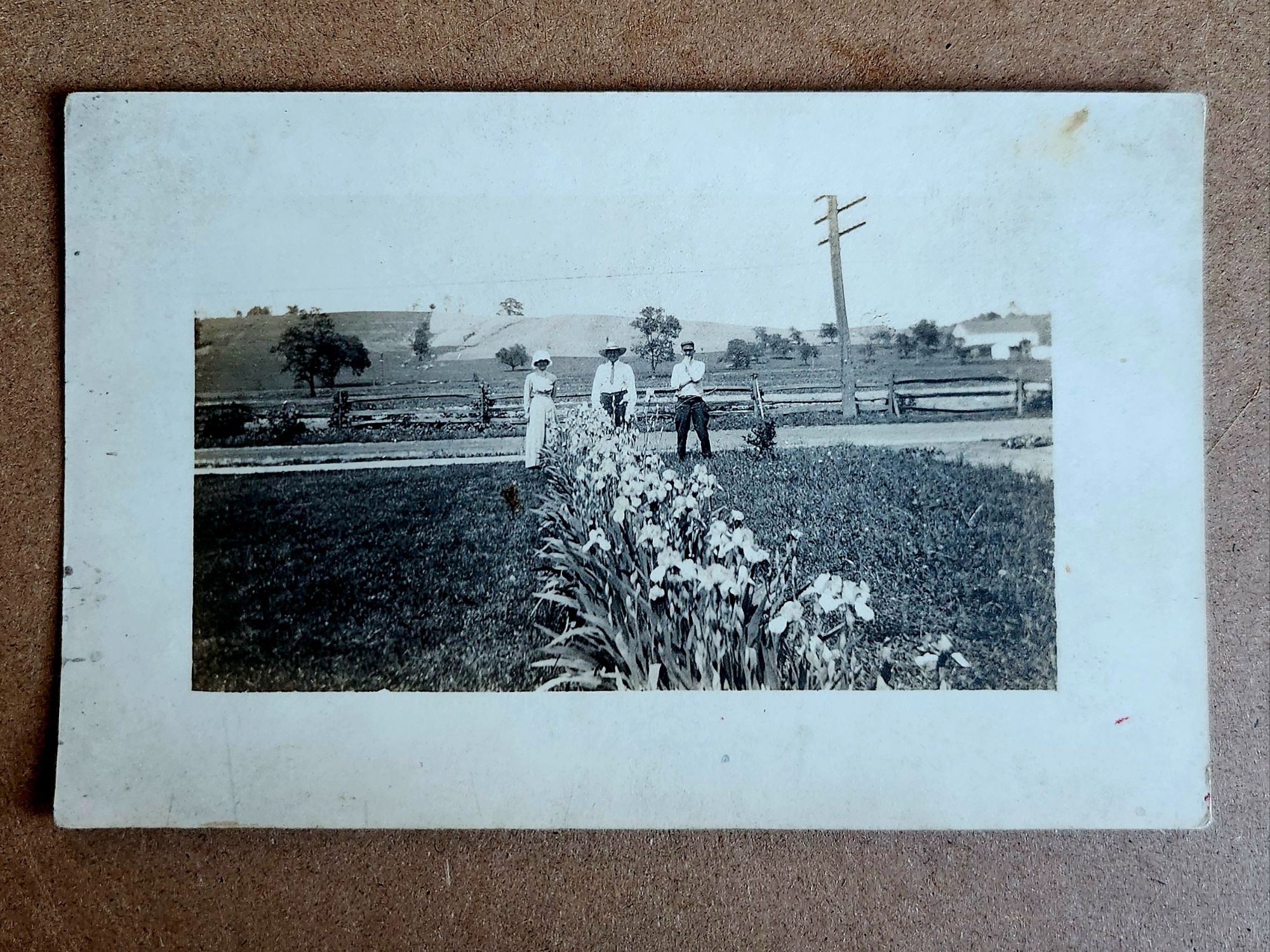

Mrs. H pointed to the one with the iris. Nina looked closer. The composition was deliberate. Bold strokes against a spare background.

“Your friend will send you more postcards?”

“She promised,” Nina replied.

“Good,” Mrs. H smiled. “We get bored without friends.”

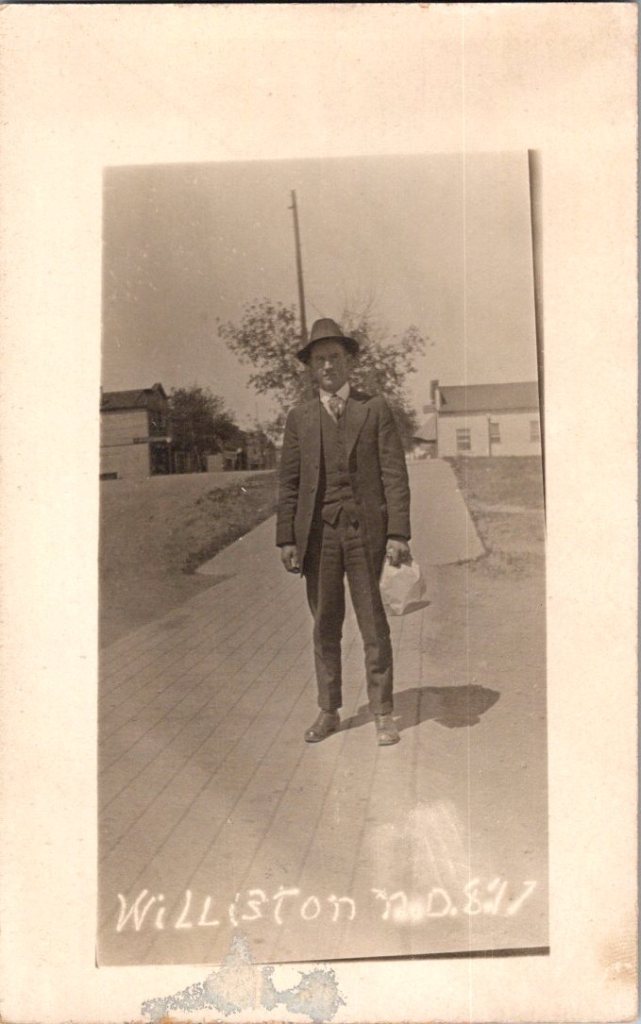

George had haunted thrift stores his whole life. Mostly he looked for tools—socket wrenches, levels, hand planes that still had their blades. Things he could use or restore.

Now he looked for postcards too.

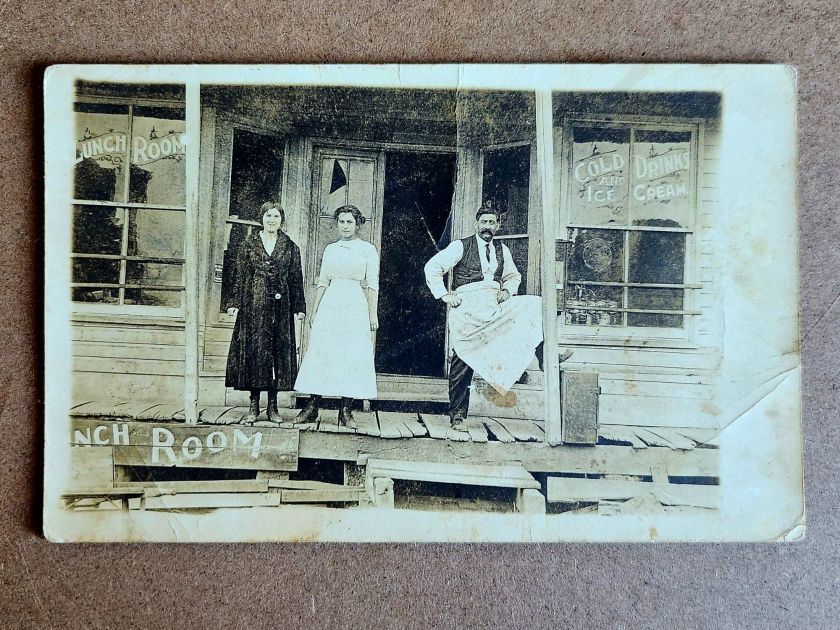

The Goodwill in Red Wing had a basket of them near the register. Fifty cents each. He sorted through slowly. Tourist shots of the Badlands. A faded view of the State Capitol. Then he found a few good ones.

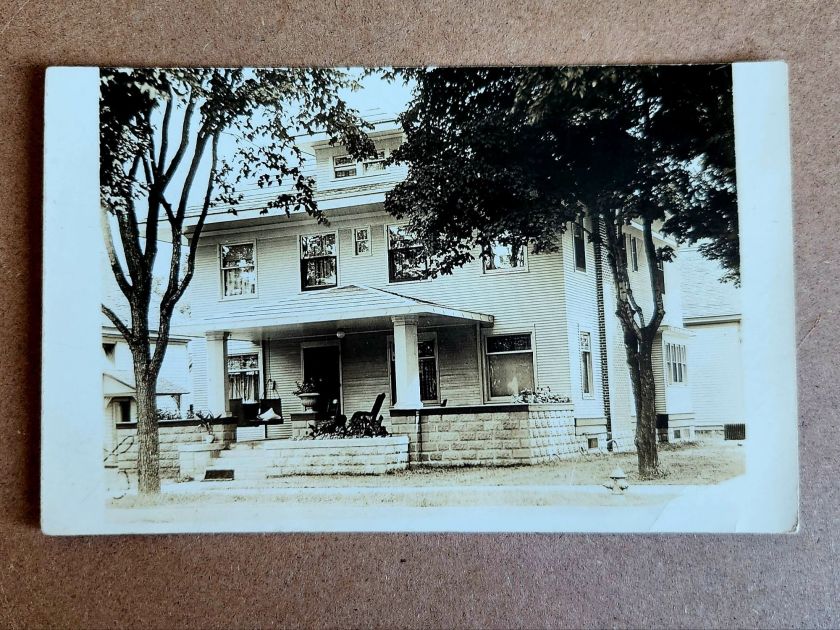

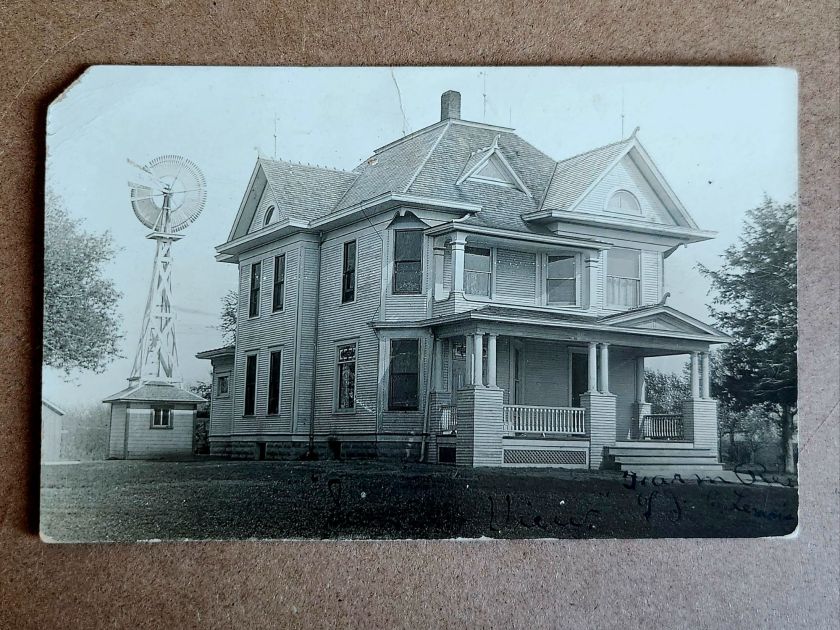

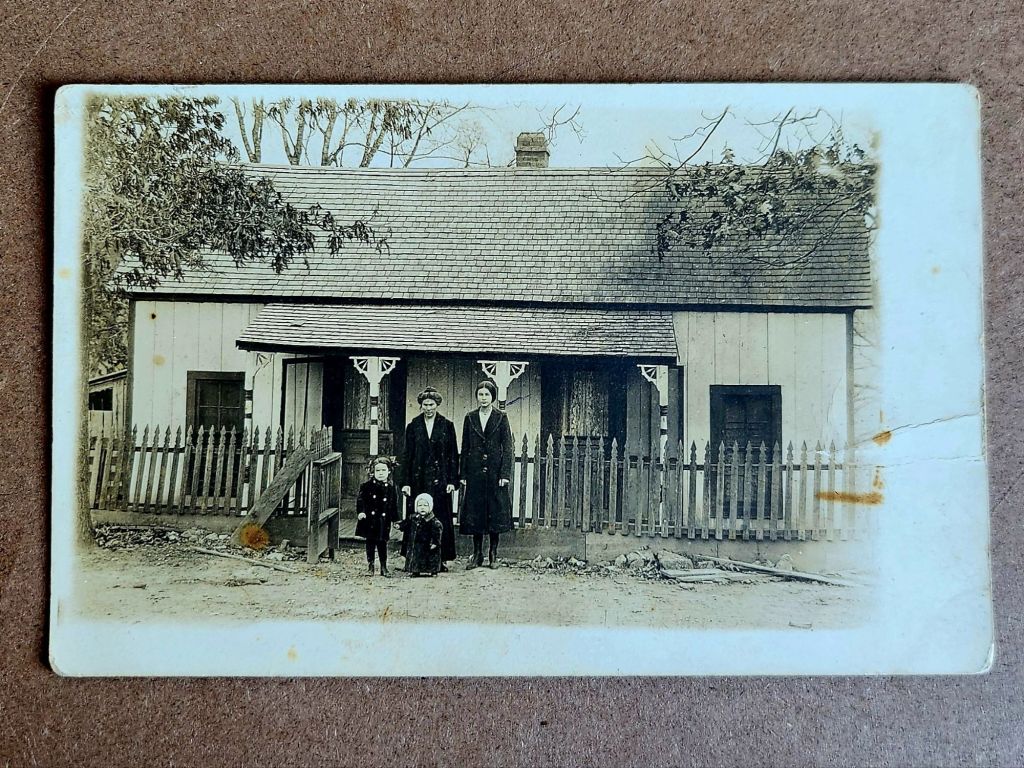

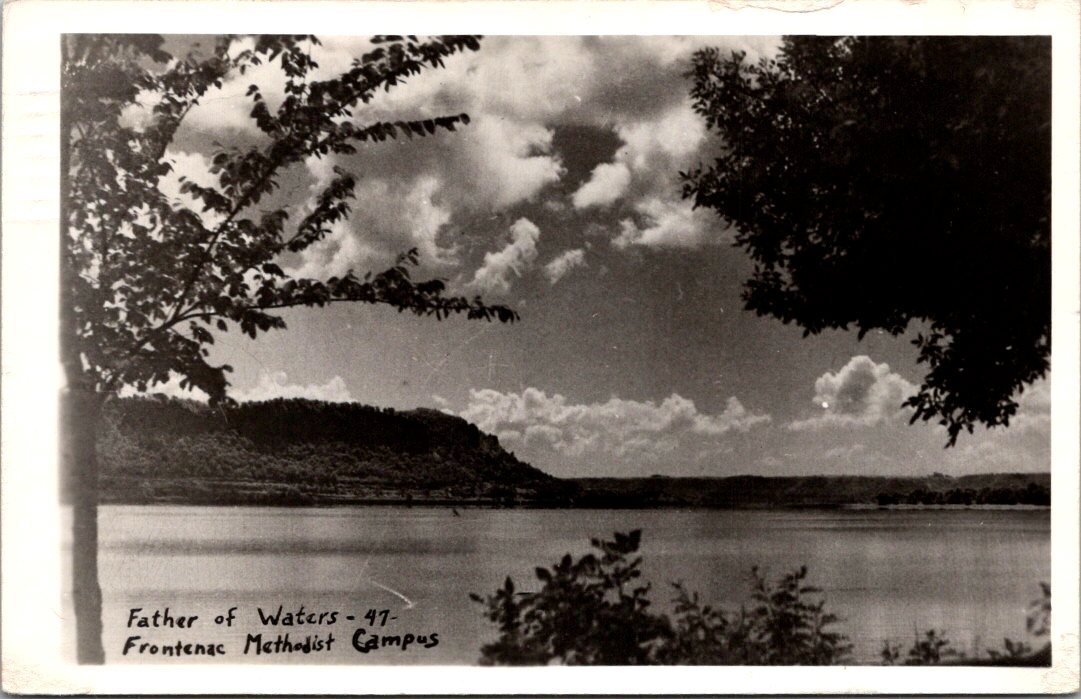

A real photo postcard showing Lake Pepin framed by trees, “Father of Waters” etched in careful script. The water stretched wide and calm, clouds massed above the bluffs.

A color card of Minneapolis Public Library, the old red brick building with its round tower and arched windows. George remembered when they torn it down in 1951.

A chrome card showing a white horse leaning over a fence, red barn and farmhouse in the background.

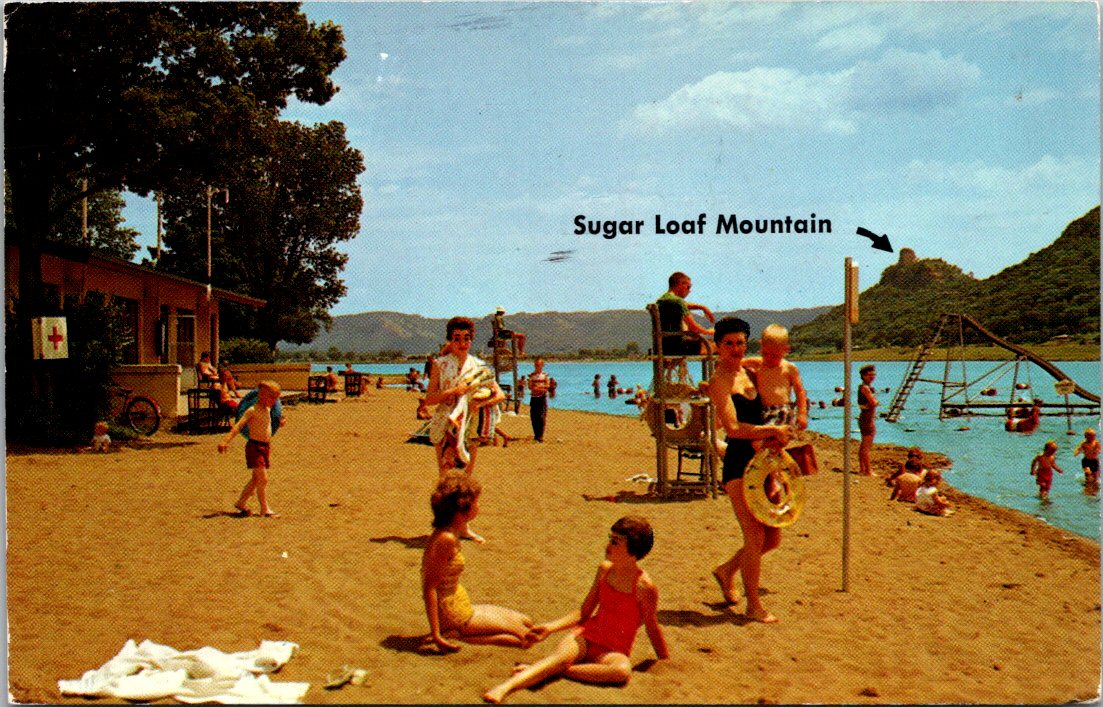

And then—George stopped. Sugar Loaf Mountain near Winona. A beach scene, families on the sand, kids on playground equipment, swimmers in the water. The mountain rising behind them.

He was transported to that very day. Their family had been right there, doing exactly that. The kids running between the beach and the playground. The particular blue of the water. How his wife had packed sandwiches that got sand in them and nobody cared.

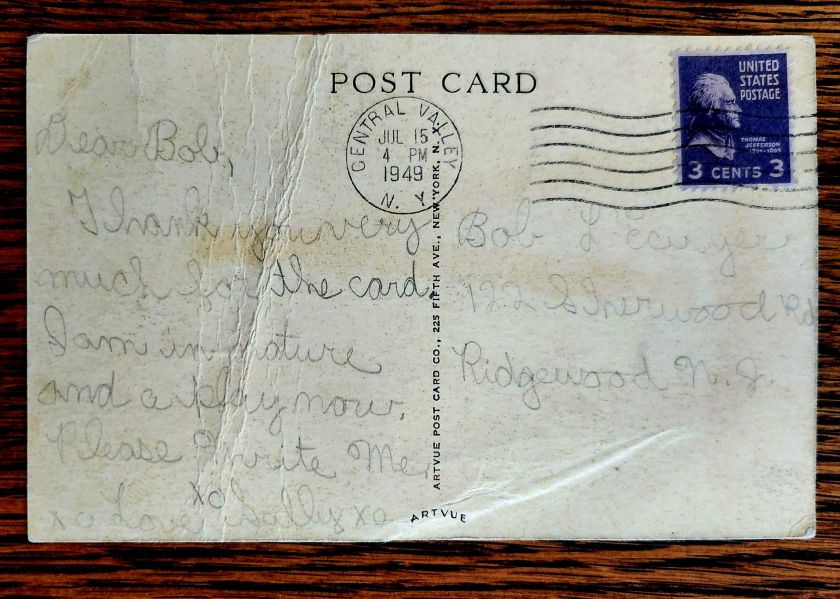

George bought all four cards. Two dollars total. At home he examined them under the desk lamp before he got to thinking about each message.

He wrote to Emma:

Found this real photo from Lake Pepin. “Father of Waters” they called it. Your wanderlust comes honestly—this river goes all the way to the Gulf. Love, Grandpa

To Jack:

Get to the good old libraries while you can. This one is gone already! Love, Grandpa

To Lily:

See how the fence posts get smaller as they go back? That’s tricky to draw! Give it a try. Love, Grandpa

He paused at the fourth card, and let out a small sigh. Sugar Loaf Mountain, seems like another lifetime. Finally, he wrote:

This one is for you, kiddo. Reminds me of you and the guys and Mom. Fun times! Love, Dad

George added addresses and stamps. Put on his coat and walked to the mailbox, a short stretch of the legs that he now enjoyed. A chickadee called from the pine tree across the street—its clear two-note song cutting through the cold afternoon air.

wake up with wanderlust, too?

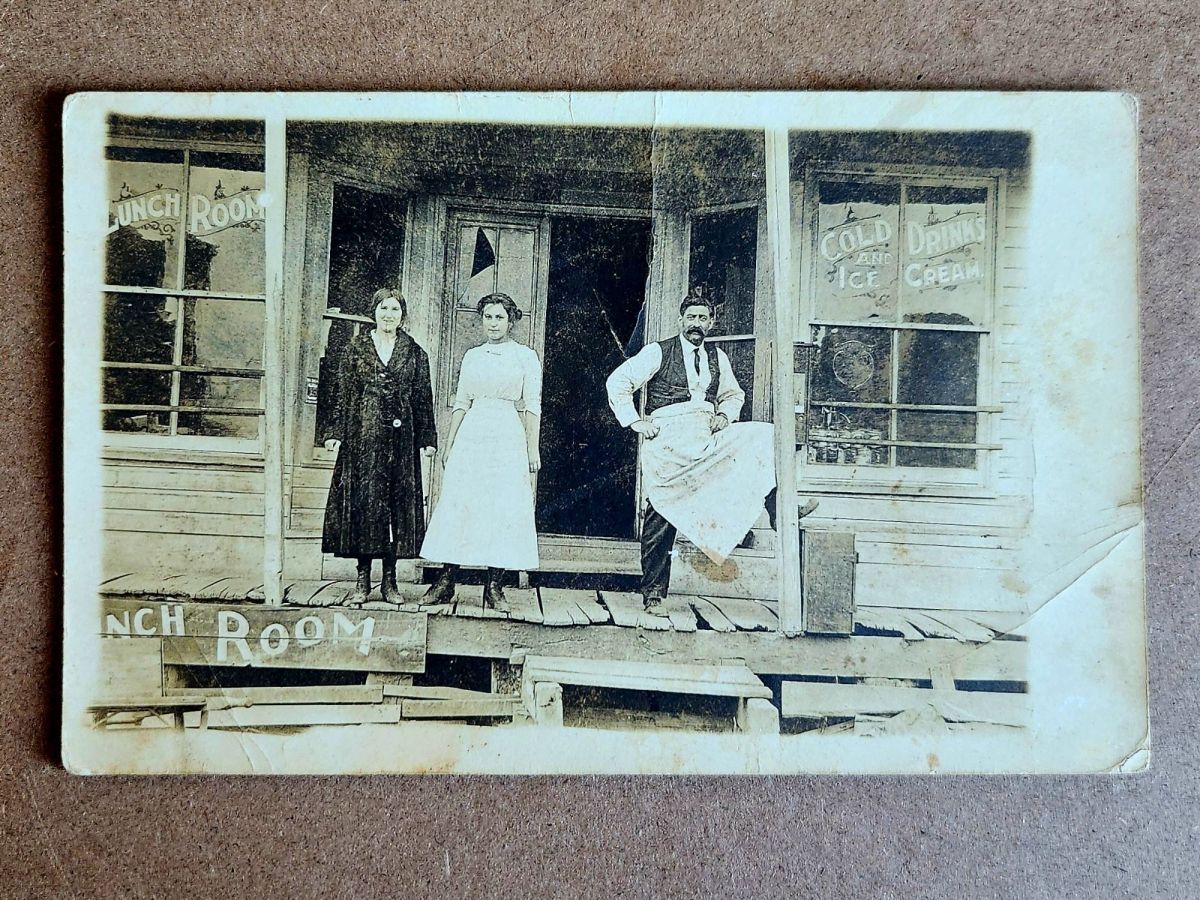

Though the story is fiction, vintage postcards are still a fun way to explore.

Browse the selection at our eBay store