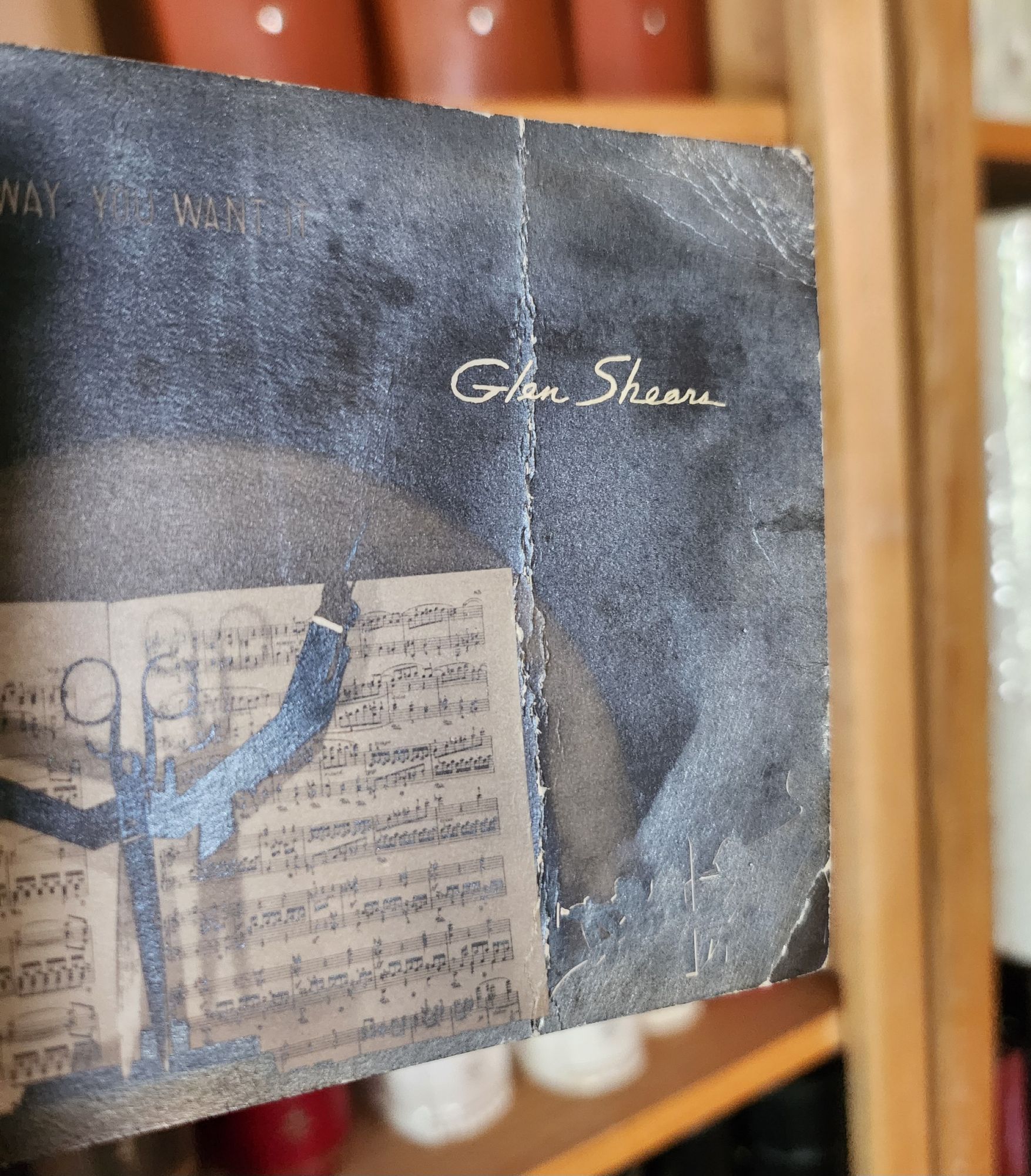

featured postcard~

rare novelty card still holds a mystery

An early 20th century novelty postcard featuring humorous photography and personal correspondence from Missouri.

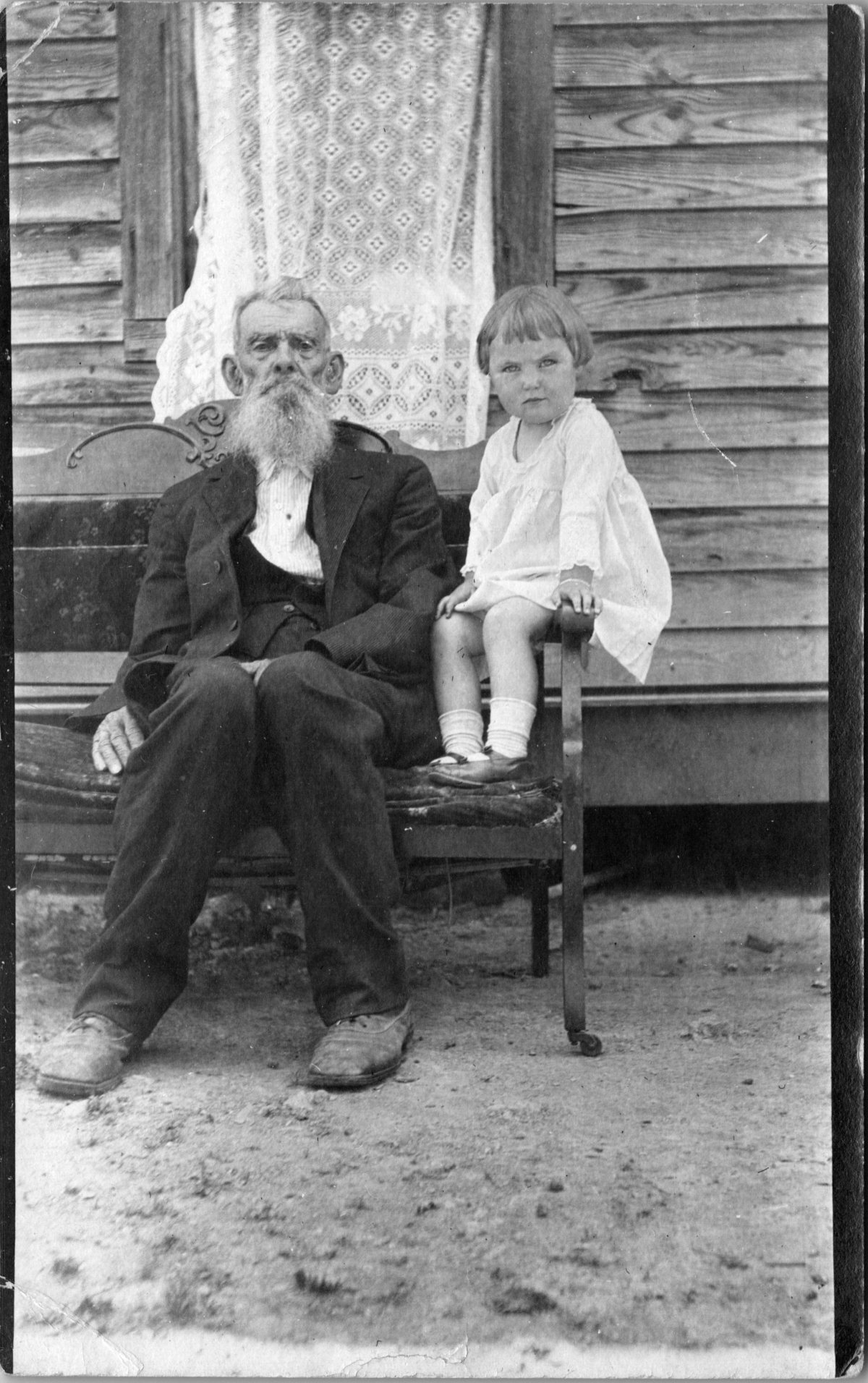

Front of the card: The photograph shows a young Black man in white shirt, suspenders, and dark trousers, grinning while holding a large broken umbrella overhead in a playful pose. Below reads the humorous caption “A little disfigured, but still in the ring”—typical novelty humor from the postcard craze era. A black border frames the photograph on cream cardstock.

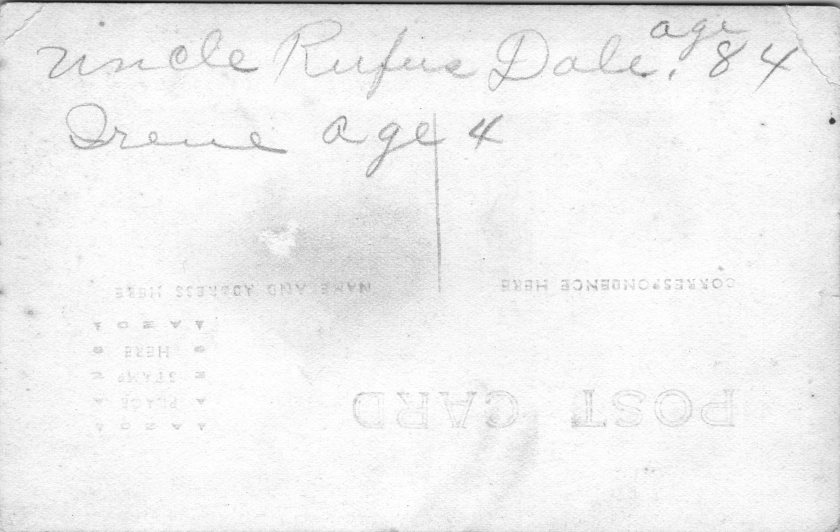

Back details: The reverse bears “Carbon Photo Series No. 513” identifying the commercial publisher’s series. Addressed to Miss Grace Skillman in Pleasant Hill, Missouri, with a green 1-cent Franklin stamp and clear 1908 postmark. The handwritten message describes an exhausting early morning wait in Lee’s Summit for “Brother and Frank,” and promising a longer letter that evening.

“Still in L.S. haven’t slept but about ten minutes. My eyes looks like two burnt holes in a blanket. Brother and Frank hasn’t come yet. I will wait till 7.30 and then go home. Will write tonight. Just finished my breakfast. I will eat if not sleep. I got here ten till five.

Condition and Appeal: The sepia-toned image displays characteristic early photography with some age spots, and a nicked corner. The image and reverse side remain in good condition with clear photography and legible handwriting. The “Carbon Photo Series” indicates premium production using carbon-based printing methods prized for superior image quality and archival stability. Grace Andre Skillman was born in Pleasant Hill in 1889, making her nineteen when she received this card. The message and the lack of formal salutation and signature suggest this is casual ongoing family correspondence. As a result, the author of the postcard remains a mystery.

Vintage novelty postcards are increasingly collectible, especially numbered commercial series with documented recipients. Collectors of African-Americana may find the image appealing and relatively rare. The combination of carbon printing technology, humorous subject matter, and personal correspondence is of interest to collectors of vintage photography, postcard enthusiasts, genealogy researchers, and those focused on early 20th century American social history and communication.

Introducing~

The Posted Past Art Card Gallery

A selection of Larry L’Ecuyer’s watercolor landscapes are on display in our Online Art Card Gallery. Fitting as our first show. Enjoy!

NEWS & UPDATES~

art card call for submissions is open

The World’s Smallest Artist Retreat (our P.O. Box) is awaiting your art card submission. Follow one rule to join the next open show. Details here!

Art card kits now in stock

Our Art Card Kits are perfectly-packaged as a fun, creative activity for you and a friend to complete in as little as an hour or made into a lovely afternoon.

The kit includes two postcard blanks, six vintage finds curated to the chosen theme, and a bundle of collage goodies for your whimsy. There is a free gift inside, too!

Once you’re done, surprise someone with an original art card in their mailbox. Or, send it back to us to include in the next online show. Either way, you’ll have cultivated a little joy in your garden.