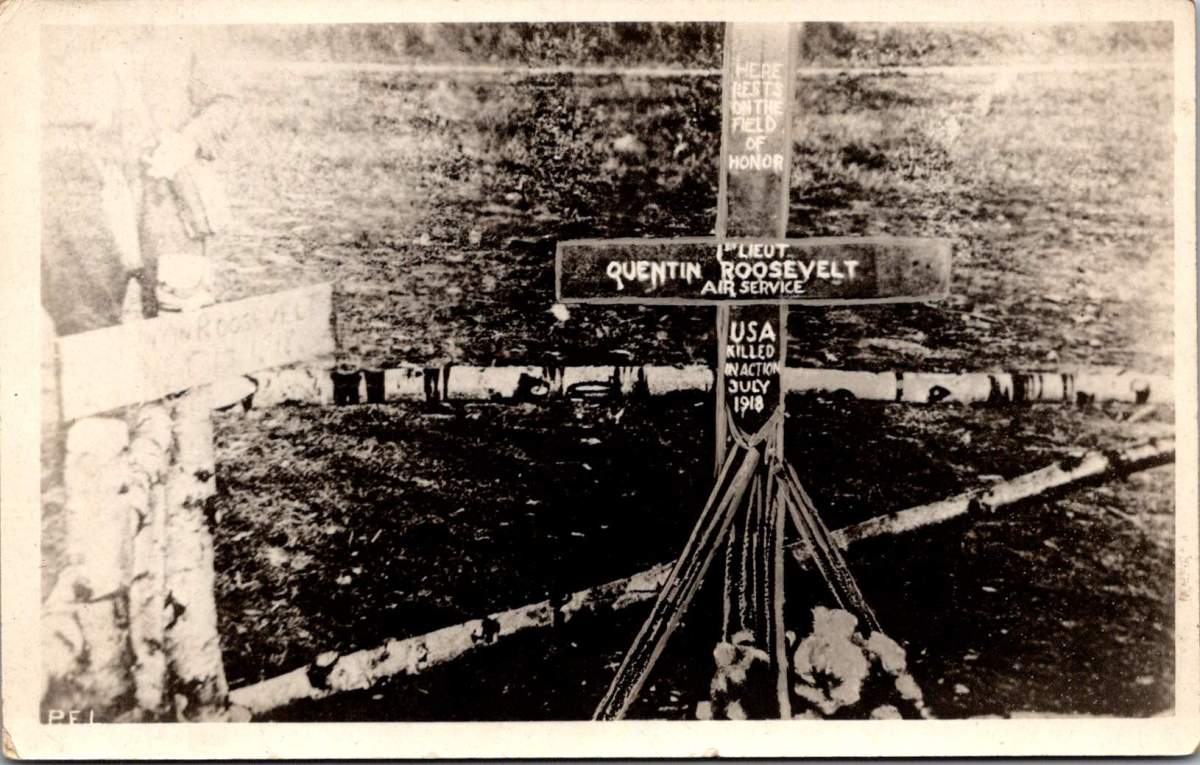

This photograph, captured by a U.S. Signal Corps photographer known only by the initials P.E.L., embodies the US vision of the first World War carefully curated by military officials. While this image evokes sacrifice, honor, and patriotism, the ones that follow emphasize air power and the ground fight.

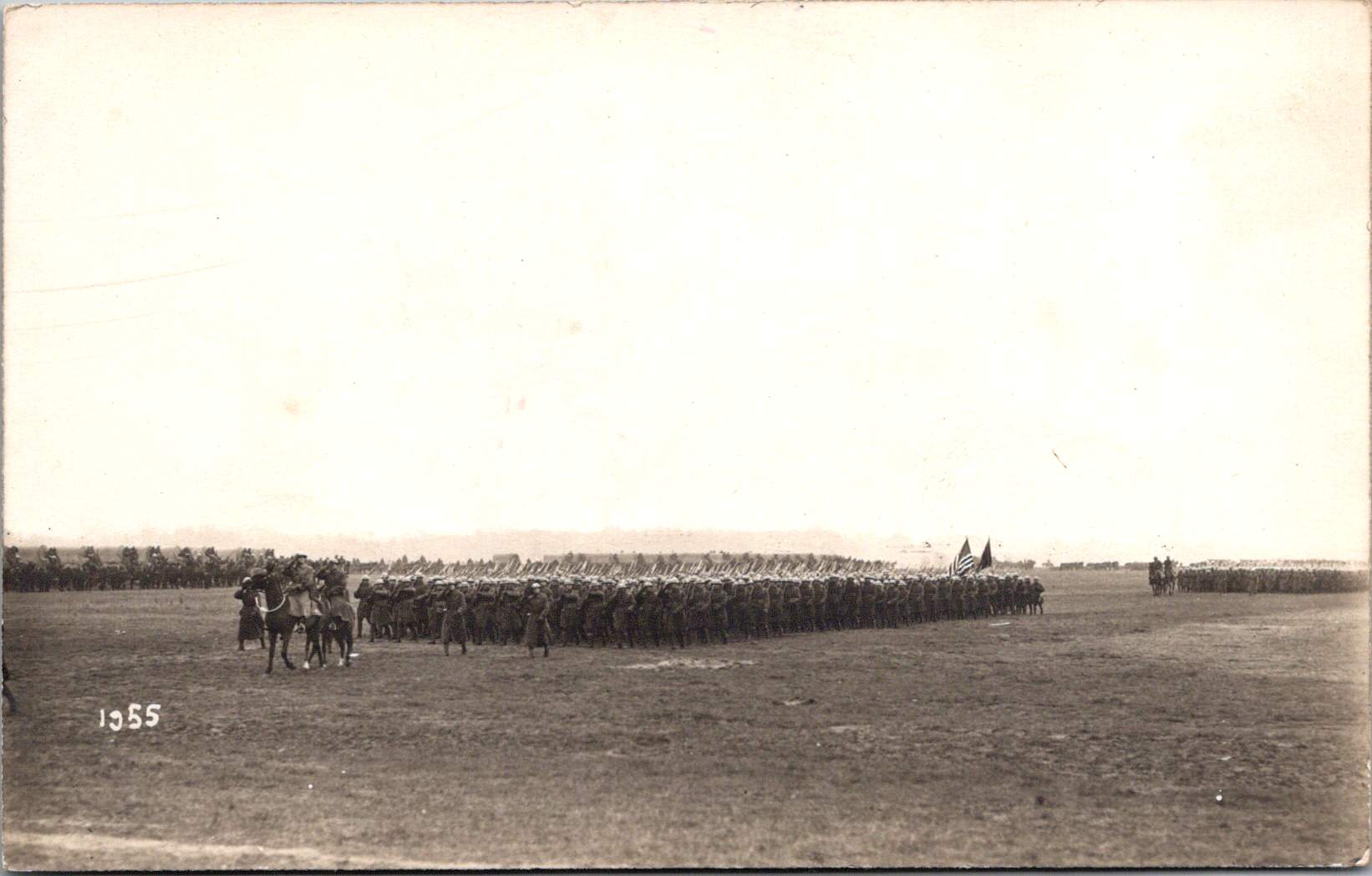

The Signal Corps photographers worked with clear directives. Their images showcased military capacity and impact: a German observation balloon in flames over Verdun, captured enemy aircraft, and troops dug into the battlefield. These photos celebrated American military achievements while maintaining a safe emotional distance from war’s realities. They framed the conflict as a grand, heroic endeavor of machines and strategy, and no bodies.

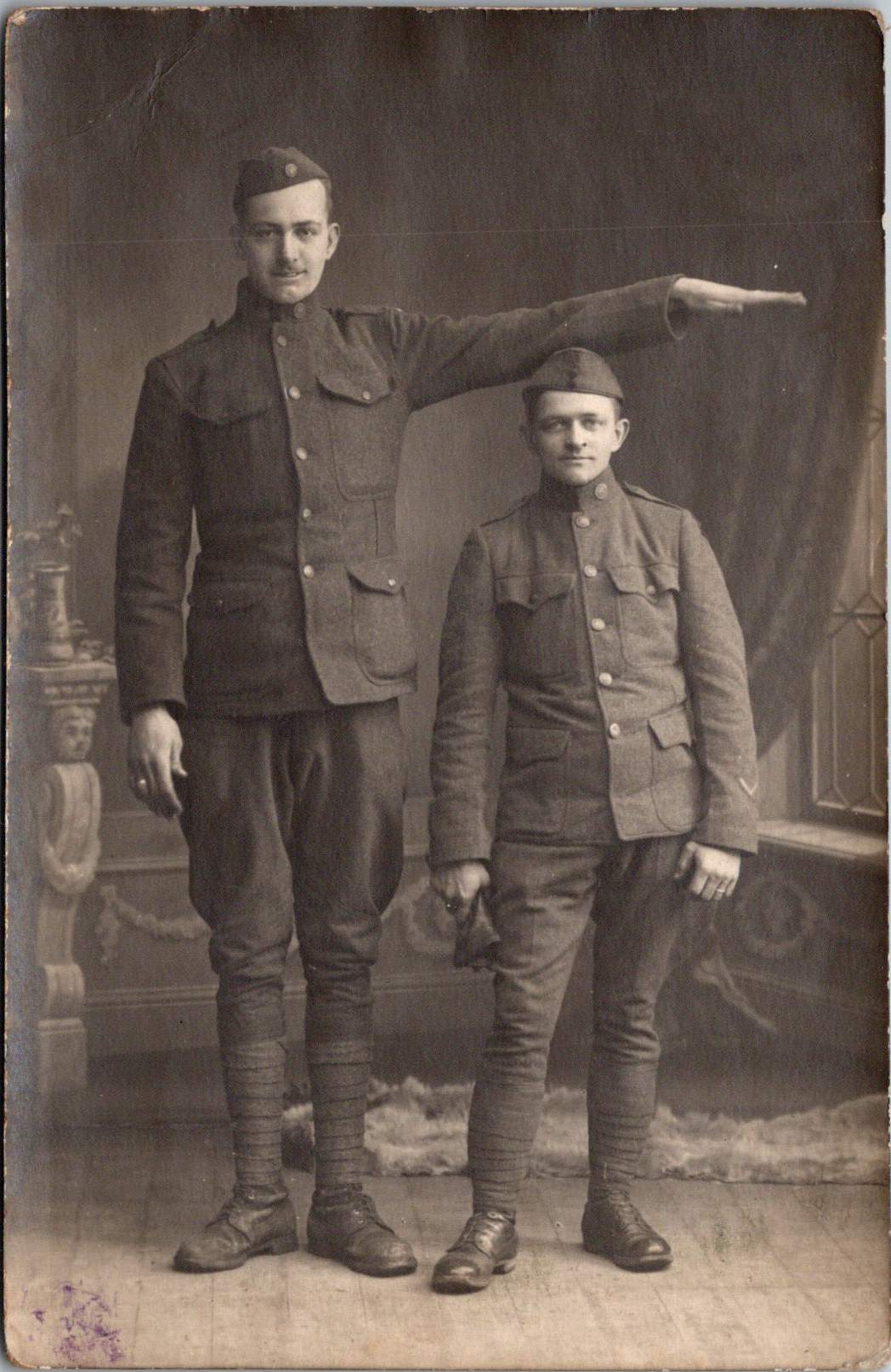

Soldier photography told different stories.

World War I marked a pivotal shift in war photography. The conflict erupted during the democratization of the camera, when Kodak’s marketing promise—You press the button, we do the rest—had placed photography in ordinary hands. For the first time, soldiers carried their own cameras to the front. They documented their experiences without oversight, censorship, or propaganda objectives.

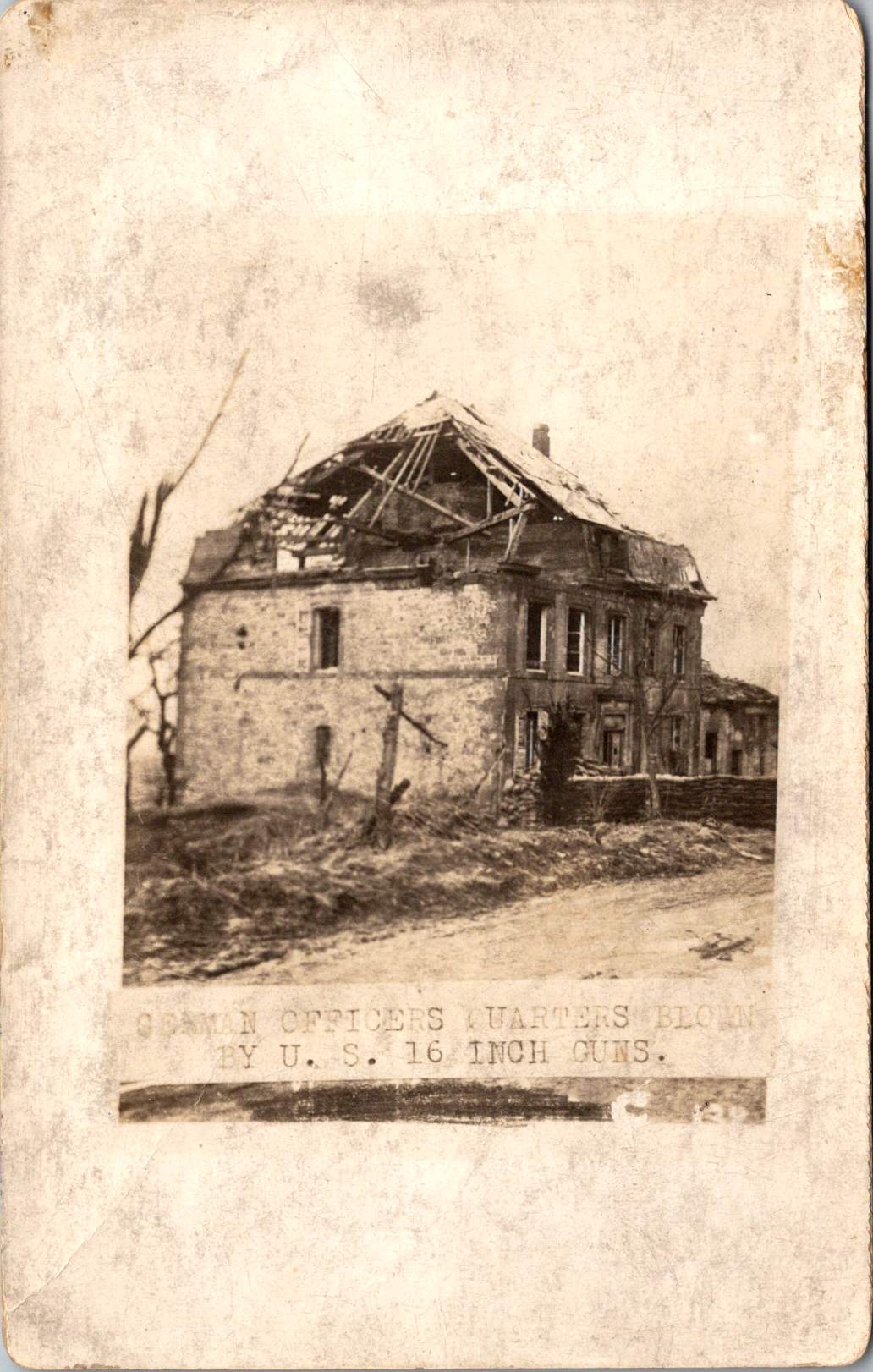

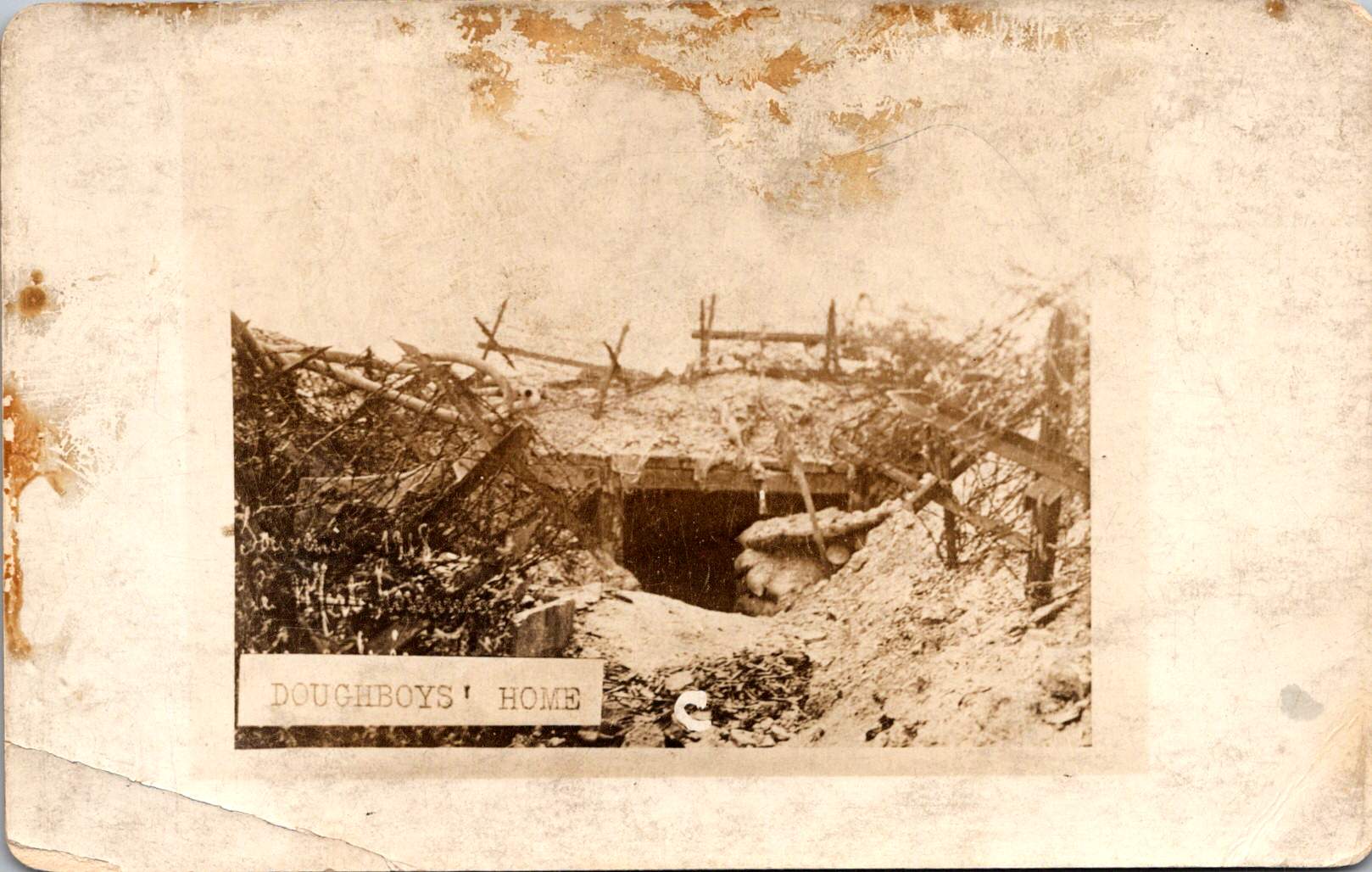

The images captured by troops and printed later at studios like Renfro & Jensen in Belmont, Arkansas reveal a more intimate perspective—the human cost of conflict. German officers’ quarters reduced to rubble by American artillery. The harsh conditions of a foxhole or a machine gun post.

These images weren’t composed for newspaper spreads or government reports. They were personal souvenirs, visual evidence of experiences too enormous to capture in words alone. They were captured on a new-fangled camera and carried home as silent witness.

Belmont, Arkansas transformed virtually overnight in 1917 from a quiet rural community into a bustling military training center. Soldiers flooded the region, bringing with them not just their uniforms and rifles, but their cameras. The town experienced a true boomtown effect as businesses sprang up to serve the influx of military personnel. Among these enterprises, the Renfro & Jensen photography studio established itself as a crucial link between soldiers’ experiences and their communication home.

Then, as demobilization began in 1918, returning soldiers sought ways to share or quietly remember what they had witnessed. Renfro & Jensen became unwitting archivists. They must have developed and printed thousands of soldier photographs—images far more frank and direct than anything appearing in newspapers or government publications. The studio workers were likely among the first civilians to confront warfare through this new technology. Each day, they processed images showing destruction, military achievements, and occasionally, the graphic aftermath of combat. Their commercial service inadvertently preserved a crucial alternative visual history of the conflict.

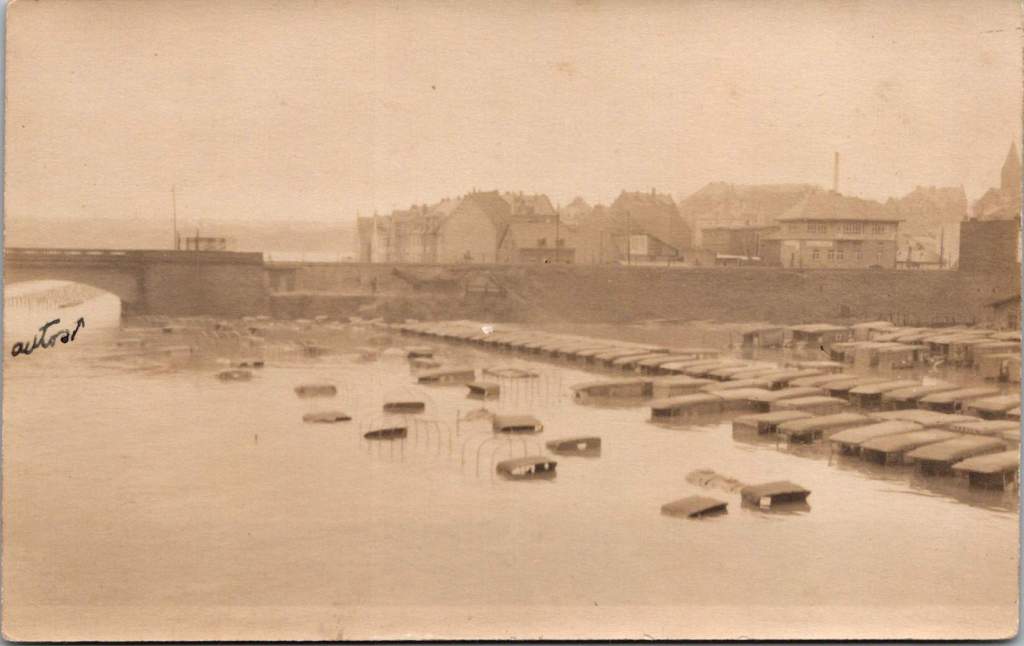

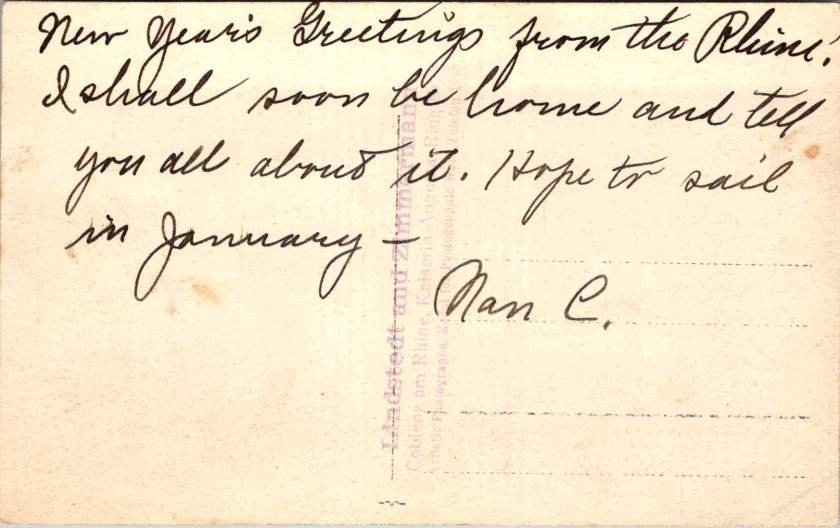

Two European-produced photographic postcards further document the war. These images, printed on distinctive European paper stock, emerged from a continent already numbed by years of destruction.

Another sixteen images — the most harrowing in the collection — can’t be shown here. The ethical boundaries of war photography persist today. What images should be shielded from casual viewing, and which realities deserve documentation regardless of their power to disturb?

Major institutional collections house millions of WWI photographs. The National Archives holds the largest repository of World War I material in the United States, with over 110,000 photographs digitized from two primary series: the American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs and the Photographs of American Military Activities. The Library of Congress maintains extensive collections, including the American National Red Cross Collection with over 18,000 digitized negatives showing wartime activities.

Beyond these institutional repositories exists a vibrant world of private collectors who often hold the most provocative and unfiltered images. These private collections sometimes reveal perspectives absent from official archives. Photographer Carl De Keyzer discovered approximately 10,000 archival glass plate and celluloid negatives from WWI scattered across Europe, many in private hands. From these, he selected 100 to reproduce in stunning detail, revealing aspects of the conflict previously unseen in such clarity. Some of the most compelling battlefield imagery exists in small personal collections—albums like this one that have been kept by families of veterans, passed down through generations, their contents rarely exhibited publicly.

The grave of Lieutenant Quentin Roosevelt is quite enough for many. It symbolizes loss while sparing us its visceral reality. But the full photographic record of the conflict includes truly heinous realities—corpses tangled in barbed wire, faces distorted by gas, bodies rendered unrecognizable by artillery.

While official photographers were tasked to frame narratives that supported war efforts, some soldier photographers refused to turn a blind eye. They captured what they witnessed, creating very personal views that continues to challenge our understanding of history. Their lenses documented what words alone could never convey—the irredeemable human cost of modern warfare.