In this age of instant digital communication, the persistence of physical postcards presents an intriguing contradiction. These rectangular pieces of cardstock—designed to carry both image and correspondence through postal systems without an envelope—serve as artifacts of a communication method that had its heyday a century ago. But rather than disappear entirely, postcards have evolved in novel ways that tell us even more about who we are.

Why We Seek the New

Humans have always been drawn to novelty. Our brains light up at the unfamiliar—it’s a survival mechanism that once helped our ancestors notice changes in their environment that might signal danger or opportunity. But our relationship with novelty runs deeper than vigilance. We seek out new experiences, objects, and sensations even when no practical threat or benefit is apparent.

This human attraction to novelty serves several purposes. First, it provides simple pleasure—the dopamine release that accompanies discovery keeps us engaged with our surroundings. Second, it helps us learn and adapt—new situations force us to develop new skills. Third, it offers social currency—being the first to discover, own, or report something novel (even if untrue!) gives us a kind of status within our communities.

Perhaps most fundamentally, novelty helps us fight against the deadening effect of habituation. We become blind to what remains constant around us, a psychological phenomenon called “sensory adaptation.” Think of how you stop noticing a persistent background sound, like traffic noise. Novelty jolts us back into conscious appreciation, like noticing the birdsong instead, making us sense the familiar differently.

With mass-produced consumer goods, we often pursue novelty through customization or unique variants—like these postcard alternatives. They satisfy our craving for something special while maintaining connection to recognizable forms. Even novelty doesn’t stray too far from the familiar.

Technology Becomes Art

As technologies age and are replaced by more efficient methods, something interesting happens—the displaced technology often shifts from the realm of utility to the realm of artistry and craft. What was once valued primarily for function becomes appreciated for form, precision, and the visible human touch.

Letterpress printing was an extraordinary innovation of its time and once the standard for all printed matter. It was largely replaced by offset printing in the 20th century and later the digital methods we use today. But rather than disappearing, letterpress evolved into a premium craft, prized for its tactile quality and visible impression on paper—characteristics that were originally just side effects of the technique, not its intended purpose.

The same transformation happens with many technologies: vinyl records, film photography, mechanical watches. As digital alternatives take over the functional role, the analog predecessors become vessels for history, craftsmanship, ritual, tactile pleasure. They move from being tools to being experiences.

This pattern helps explain our collection of novelty postcards. Somewhere in the middle of last century, the standard paper postcard was functionally superseded by digital communication, freeing it to evolve into these more elaborate, less practical forms. They represent a technology in its artistic phase—no longer bound by strict utility, but free to explore expressive and sensory possibilities, along with kitsch and commercialism.

Utah in Copper Relief

The copper-embossed Utah souvenir represents one of the more elaborate departures from traditional postcard design. The metallic rectangular plate features a raised topographic outline of the state with embossed illustrations of regional landmarks and attractions. The word UTAH is prominently displayed at the top, while places like Vernal, Provo, Cedar City, and St. George are labeled at their approximate locations. The copper medium gives the piece warmth, with a decorative scalloped border framing the state’s geography and securing the paper card below.

The manufacturing process likely involved die-stamping or embossing thin copper sheeting, a technique that dates back to the late 19th century and regained popularity in mid-20th century souvenirs. The tactile nature of the raised elements invites touch, creating a multisensory experience unavailable in traditional flat postcards. The utility of this object as actual correspondence is significantly diminished—the copper surface resists easy writing, and its weight requires additional postage and hand-canceling. It’s more a miniature commemorative plaque that happens to maintain postcard dimensions.

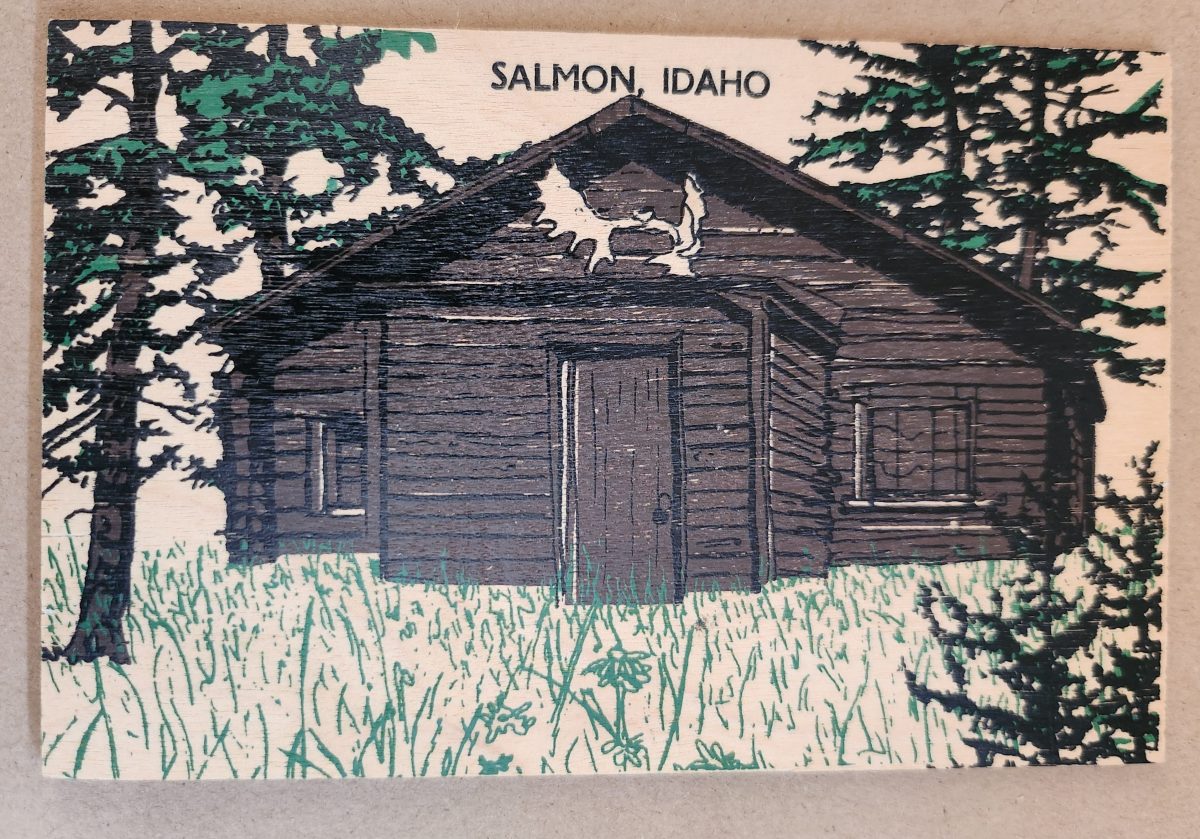

Woodsy Aesthetics

Let’s look closer now at a novelty postcard featuring a cabin in Salmon, Idaho, printed onto a thin wooden substrate and depicting a rustic cabin nestled among stylized pine trees. The scene employs a limited color palette—brown and black for the structure and green for the surrounding vegetation—lending it a deliberately simple aesthetic that echoes both woodcut prints and traditional lithography.

The simple text at the top identifies the location without intruding on the scene. The artwork itself employs minimal detail, capturing the essence of rural life rather than photographic accuracy. The manufacturing process of printing onto thin wood veneer allows for mass production, while adding a specific scene, location name, and ink color for customization.

This card’s rustic medium and subject matter work in harmony, creating a self-referential object where the material reinforces the message—a wooden card depicting a wooden structure set within a forested landscape. The medium becomes part of the message, suggesting authenticity through material consistency. Though mass-produced, it strongly evokes a rural sensibility.

Framed Vistas

Our souvenir from Yellowstone National Park adopts yet another approach. This card features a stylized illustration of Yellowstone’s grand canyon and waterfall printed on cardstock and mounted on a wooden backing.

The artwork employs a palette of oranges, purples, blues, and whites to capture the dramatic landscape, with the falls rendered as a white vertical streak against colorful canyon walls. Dark silhouettes of pine trees frame the scene, while puffy clouds hover in a light blue sky, held inside a purple border. The stylized typography echoes vintage travel posters from the early to mid-20th century. The entire image is mounted or printed on a natural wood base, visible as a frame around the illustration.

This card’s production combines offset printing with a wooden substrate—a look that recalls both traditional woodblock prints and mid-century travel advertisements. The design deliberately evokes an era of American national park tourism when artistic posters commissioned by the Works Progress Administration and the National Park Service established a distinctive aesthetic for natural landmarks.

Playful Puzzles

The Disney puzzle postcard introduces an element of interaction we haven’t seen before. This card features Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck, Daisy Duck, Pluto, and Goofy arranged in a group pose against a blue-and-white checkered background. The message reading “Hi From The Whole Gang” in bubble text curves around the edge of the image.

This item turns a postcard into a simple jigsaw puzzle—die-cut pieces that can be jumbled and reassembled to reveal the printed image. The manufacturing process involved full-color printing followed by precision die-cutting to create interlocking puzzle pieces, then applying a thin adhesive film to maintaining the card’s overall integrity for mailing.

This souvenir represents a curious hybrid—a postcard that actively invites its own disassembly. The Disney characters themselves represent another layer of nostalgia, combining America’s animation icons with the traditional postcard format to create an object that references multiple forms of 20th-century popular culture simultaneously. But only modern technology could accomplish these manufacturing details, a playful combination of familiar and fresh.

Magnetic Memories

The Will’s Hardy Trees and Seeds magnetic card is the one in our set with the most layers of both meaning and making. See packets, postcards, fridge magnets, and agricultural Americana all combine in this take home treasure.

The 1909 seed catalog cover is a contemporary image inspired by the real-life Oscar H. Will & Co. of Bismarck, North Dakota. The vibrant illustration displays pansies in various colors—purple, yellow, orange, pink, and white—arranged in a bouquet. Text identifies the company’s 26th year of operation and describes their products as the “choicest and most beautiful on earth”.

A small purple circle overlay on the plastic film cover announces the item’s true nature: a magnetic postcard to send as a gift. Despite its historical appearance and postcard dimensions, the object is actually a refrigerator magnet that merely references seed catalog and postcard aesthetics. The production involved digital printing on magnetic sheet material, applying a printed paper backing, and slipping into a plastic cover with instructions to mail the gift in an envelope.

As a novelty item, it reveals a peculiar circularity. A reproduction of a commercial artifact (seed catalog) transformed into a correspondence medium (postcard) further transformed into a decorative household item (refrigerator magnet). Somehow, we love each iteration all the more.

Nostalgia Squared

What these examples share is a relationship with nostalgia that operates on multiple levels. They aren’t simply nostalgic; they engage in a looping nostalgia—nostalgic representations of already nostalgic forms.

The copper Utah relief draws upon mid-century tourist souvenirs, themselves designed to evoke frontier-era maps and territorial markers. The Salmon cabin employs modern production techniques to simulate traditional woodcuts nad print, which were themselves often romanticized depictions of rural life. The Yellowstone cards references mid-century national park posters that were already stylized interpretations of natural wonders. The Disney puzzle incorporates cartoon characters who have become nostalgic cultural icons, presented in the format of childhood games. The Will’s Seeds magnet reproduces early 20th-century commercial art that was, even in its original context, employing Victorian aesthetic sensibilities.

This layering of reference creates objects that are remarkably dense with cultural signifiers despite their modest physical dimensions. They offer not just a connection to place and time but to the ways we’ve represented ourselves and our interests through commercial souvenirs.

Our apparent need for novelty, then, might be better understood as a need for continual context. Each new postcard iteration doesn’t merely replace what came before; it absorbs and references it, creating objects that function as compact archives of our evolving relationship with the characters and places we cherish.

These novelty postcards sit at an interesting crossroads of commerce, craft, and communication. They represent what happens when a formerly utilitarian object—the humble postcard—is freed from its purely practical obligations and allowed to evolve along lines dictated by sentiment, aesthetics, and novelty.

In a world increasingly dominated by digital experiences, these physical novelties offer something screens cannot—texture, weight, presence. They satisfy our hunger for the tangible. Their quirky, sometimes impractical forms speak to a human need more fundamental than efficient communication: the need to hold something unique in our hands, and to feel a physical connection to places we’ve been and experiences we’ve had.

The postcard itself is and was a very simple concept and object that, over time, has become a medium for ongoing conversations about permanence and impermanence, about what we value over time, and about the tension between utility and sentiment. In their various novel forms, these more-than-postcards tell us about places we’ve been and how we’ve chosen to remember and delight in those places—a correspondence not just between people, but between past and present.

Discover more from The Posted Past

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I really like how you described the way postcards and printed pieces can surprise us and feel more meaningful than another screen notification. At Laguna Digital, we see this same reaction when people choose custom postcards or photo prints, there’s something about holding a physical piece that instantly feels more personal and memorable. Novelty today isn’t always about something new, it’s often about rediscovering the simple things that connect us.

LikeLike