As we examine each postcard, we’ll uncover the story of Tempe’s development and explore how each generation has contributed to the city’s evolving landscape.

The Hackett House: Victorian Charm in the Desert

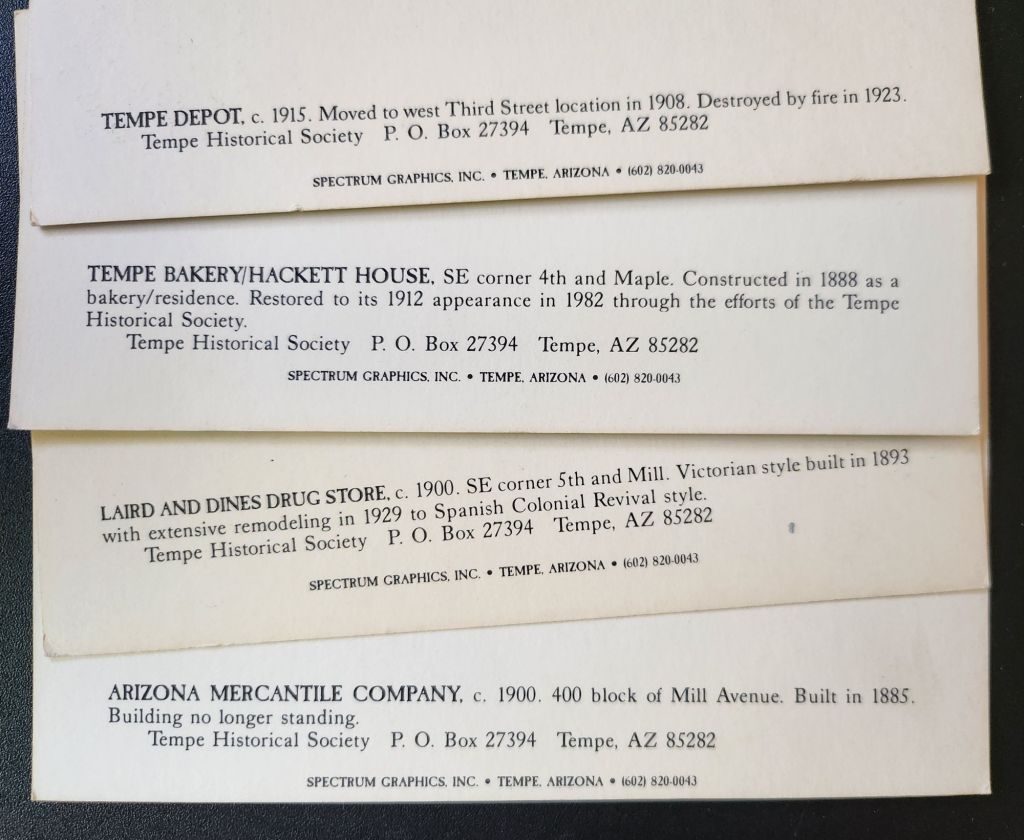

Today’s journey begins with a postcard depicting the Hackett House, a quaint building constructed in 1888. This red brick structure, Tempe’s oldest of its kind, stands as a testament to the city’s early days. With its distinctive turret and elegant design, it exemplifies the rare Arizona Territorial Victorian commercial style.

Originally built by German immigrant William Hilge as Tempe’s first bakery, the Hackett House’s location near the Hayden Flour Mill, the railroad, and the Territorial Normal School (now Arizona State University) nods to the earliest urban planning in Tempe. The postcard captures the building’s 1912 appearance, which was painstakingly restored in the 1970s.

The history of the Hackett House mirrors Tempe’s own evolution. After its days as a bakery, it served as a residence and later a boarding house. It earned its current name when Estelle Craig, Tempe’s first telephone operator, married Roy Hackett in the old bakery house. By the 1980s, when our postcards were likely printed, the Hackett House had already been recognized for its historical significance and placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Tempe Depot: The Arrival of Progress

Our next stop is the Tempe Depot, captured in a postcard circa 1915. The image shows a steam locomotive at the station, a small group clustered for the photograph. This scene represents a pivotal moment in Tempe’s history, symbolizing the city’s connection to the wider world.

The arrival of the Maricopa and Phoenix Railroad in 1887 transformed Tempe from a small farming community into a thriving center of commerce. The depot, built in 1907, served as a vital link for both passengers and freight, fueling Tempe’s growth and prosperity. Though the original structure was lost to fire in 1923, this postcard preserves its memory and significance.

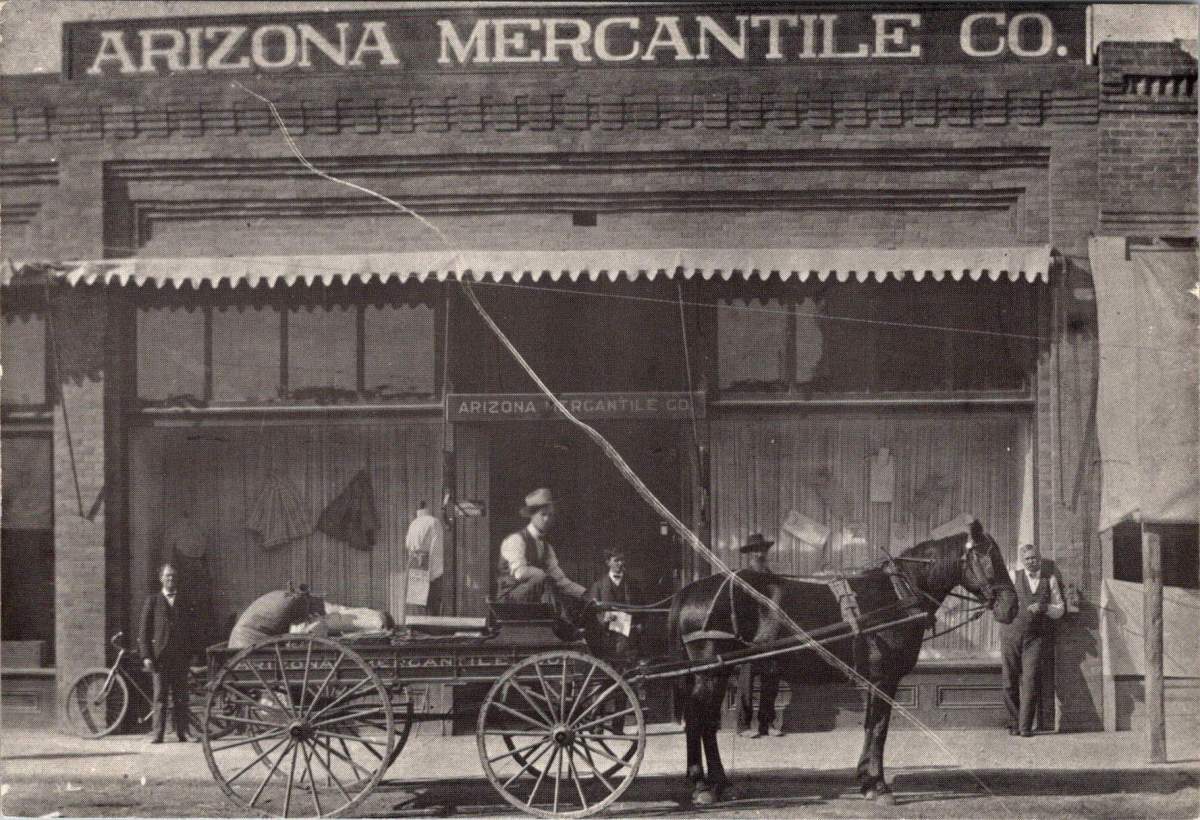

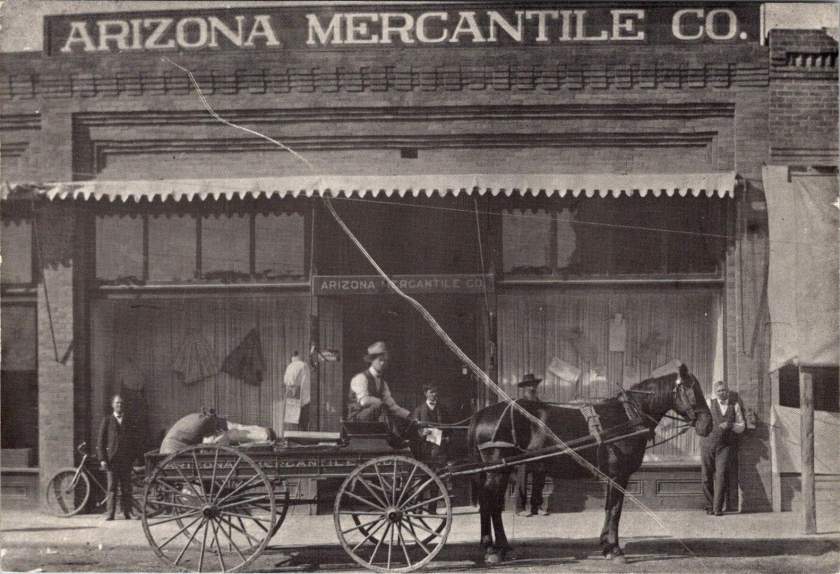

Arizona Mercantile: Commerce in Early Tempe

The next postcard features the Arizona Mercantile Co., a sturdy brick building constructed in 1898. With its large storefront and a horse-drawn carriage parked outside, this image encapsulates the commercial heart of early Tempe.

The Arizona Mercantile Co. played a crucial role in Tempe’s economy, providing essential goods and services to the growing community. The image itself, its preservation, and later reproduction underscores the importance of local businesses in shaping Tempe’s identity and meeting its residents’ needs.

Laird and Dines Drug Store: A Corner of History

Our final postcard depicts the Laird and Dines Drug Store, circa 1900. This Victorian-style corner building, with its prominent “DRUGS” signage, offers another glimpse into Tempe’s commercial past. The image shows the particulars of storefront business, with its ornate architecture, early signage, and shades to defend against the afternoon sun.

The building went on to serve as campaign HQ for Senator Carl Hayden and Governor Benjamin B. Moeur, as well as the first town hall and post office. Renovations reflected each successive era, including a few that were later reversed. Look closely today, and the old bones still show.

Preservation: Buildings vs. Postcards

As we explore Tempe’s history through these 1980s postcards, we encounter an interesting dichotomy in historical preservation. While some buildings depicted still stand today, others have long since disappeared from Tempe’s landscape.

The preservation of postcards offers a unique window into the past, allowing us to visually experience Tempe as it once was, even when the physical structures no longer exist. The Tempe Depot postcard, for instance, preserves the image and significance of a building lost to fire, serving as a tangible link to the city’s early railroad days.

On the other hand, the preservation of buildings like the Hackett House allows for a more immersive connection with history. Visitors can walk through the same spaces, touch the same walls, and experience the ambiance of a bygone era in a way that a two-dimensional image can’t replicate.

This dual approach to preservation provides a richer, more comprehensive understanding of Tempe’s history. The postcards fill in the gaps where physical preservation was lost, while the preserved buildings offer tactile and fertile connections to the past.

Tempe’s Historic Landscape

Tempe’s commitment to preserving its architectural heritage is evident in the numerous historic properties that dot its landscape. The Elias-Rodriguez House, built in 1882 using traditional adobe methods, stands as one of the oldest surviving buildings in Tempe, representing the early Hispanic influence on the city’s development.

The Niels Petersen House Museum, a Queen Anne Victorian style home built in 1892, offers visitors a glimpse into the life of a wealthy rancher in territorial Arizona. The Old Main building on Arizona State University’s campus, completed in 1898, continues to serve the university community while standing as a proud reminder of the institution’s long history.

These pristinely preserved buildings, along with others undergoing substantial redevelopment like the Hayden Flour Mill (1918) form a network of historical touchstones throughout Tempe. They create a physical timeline of the city’s development, allowing residents and visitors alike to trace Tempe’s growth from a small agricultural settlement to a thriving modern city.

Evolving Landscapes: Tempe Through the Decades

While our postcards capture Tempe’s early history, the city’s development didn’t stop in the early 20th century. Each subsequent generation has left its mark on Tempe’s landscape, contributing important and useful additions that have shaped the city we know today.

The 1960s saw the development of the Mid-Century Modern style that has since become iconic in Tempe. Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium still defines Tempe’s landscape as a living example of Taliesin West design, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s principles and aesthetic.

Another example, Shalimar Golf Course & Estates, built in 1961 combining a golf course with a mix of single-family and townhomes all featuring the golf lifestyle. This ambitious project represented a new approach to suburban living, offering residents a blend of recreational amenities and comfortable housing. The golf course continues to operate today, though its future faces the threat of redevelopment again in 2025.

As we consider the fate of mid-century developments like Shalimar, we’re confronted with a critical question: will these more recent historical landscapes be preserved in place or will they exist only as postcards, if at all? The answer may depend on how we value and interpret the architectural and cultural legacy of the mid-20th century, and how we balance preservation with the evolving needs of a growing city.

Generational Contributions to Tempe’s Landscape

These projects, spanning a century, demonstrate how each generation in Tempe has contributed something important and useful to the city’s landscape. Each of these developments responded to the needs and aspirations of its time while also shaping the future of Tempe. They’ve created new models for residential communities, transformed the city’s relationship with its natural environment, spurred economic growth, and positioned the city as a cultural hub in the region.

Moreover, these projects have often built upon or complemented earlier developments. For instance, Tempe Town Lake is a modern creation that in some ways echoes the water management innovations seen in earlier projects like the Roosevelt Dam. The Tempe Center for the Arts, with its lakeside location, takes advantage of the views and ambiance and extends the cultural campus of the city.

This layering of infrastructure and development over time creates a rich urban tapestry that tells the story of Tempe’s growth and evolution. From the historic buildings captured in our 1980s postcards to the modern landmarks of today, each generation has added its own chapter to Tempe’s ongoing narrative.

Civic Priorities Across Eras

Examining Tempe’s history reveals how certain civic priorities persist across generations, forming a thread of continuity. The establishment of the Territorial Normal School in 1885 reflects an ongoing commitment to education that continues to shape the city’s identity today. Infrastructure development demonstrates the community’s long-standing recognition of the importance of resource management and large-scale planning.

The presence of telephone services in early Tempe, including Estelle Craig’s role as the city’s first telephone operator, reminds us the community’s need to embrace new technologies. This spirit of innovation has persisted through the decades, manifesting today in Tempe’s adoption of smart city technologies and its support for tech industry growth.

The growth of local businesses and transportation networks demonstrates a consistent focus on economic development that remains a key priority for Tempe. From the early mercantile stores to the bustling mill, and from the first railroad to modern light rail systems, Tempe has always recognized the importance of commerce and connectivity in building a thriving community.

The Past Informing Future Plans

Understanding our history plays a crucial role in shaping the future of our cities, and Tempe is no exception. The walkable, mixed-use nature of early Tempe, where residences, businesses, and civic institutions coexisted in close proximity, still exists as a memory and a footprint within contemporary urban planning that prioritizes regional accessibility and global interaction.

Preserved buildings like the Hackett House do more than just remind us of the past; they actively influence contemporary architectural styles. By maintaining these historical structures, Tempe creates a sense of continuity in its urban landscape. Modern buildings often incorporate elements inspired by these historical designs, creating a blend of old and new that gives the city its unique character over time.

Historic buildings also make spaces for modern vision and mission, as seen with the Hackett House’s current role as headquarters for Tempe Sister Cities. This practice of adaptive reuse not only preserves historical structures but also breathes new life into them, making global connections, welcoming visitors and ensuring Tempe’s relevance for future generations.

History Today and Tempe’s Future

As we look at these 1980s postcards of even older Tempe landmarks, we’re reminded that the appreciation of history is itself a constant. Each generation recognizes the value of its heritage and works to preserve it for the future. In doing so, they contribute to the ongoing story of Tempe, creating a richer, more resilient urban fabric that honors the past while embracing the future.

The challenge – and opportunity – for Tempe and cities worldwide lies in maintaining this delicate balance between preservation and progress. By thoughtfully integrating historical elements into modern urban planning, we create spaces that are not only functional and innovative but also deeply rooted in the community’s unique identity and shared history.

Crucially, thinking about the past and future opens a window into creative solutions for present-day challenges. Some old ways of desert living offer valuable clues for sustainable life in modern Tempe. The walkable nature of early Tempe, for instance, provides inspiration for reducing car dependency. The adaptive reuse of buildings like the Hackett House demonstrates how we can minimize waste and preserve cultural heritage simultaneously. The large-scale water management projects of the past have to inform us in dealing with water scarcity in an era of climate change.

As Tempe faces new challenges and opportunities, these historical images and structures serve as both guideposts and inspirations. They remind us that every generation leaves its mark, and that by honoring our past, we can create a more meaningful and sustainable future. The story of Tempe, as told through these postcards and the buildings they depict, is about continuity amidst change and working together. It’s a story that continues to unfold, with each generation adding its own chapter.

In the end, Tempe’s effort to learn from its history while boldly innovating for the future reflects those shared concerns every community faces. It shows that progress and preservation are not mutually exclusive, Rather, they are complementary forces. When balanced thoughtfully, they can create vibrant, resilient, and deeply-rooted urban and suburban communities. As Tempe faces the future, it does so with the wisdom (and the failures!) of its history as a guide, each generation ensuring that the city’s unique character and community spirit will endure for the next.