In the spring of 1865, Alexander Gardner made a series of photographs of Abraham Lincoln in a studio in Washington DC. Originally, the images were meant as source material for a later unremarkable oil portrait. Instead, one image would become a widely circulated presidential carte de visite (CDV, predecessor to the postcard) showing a contemplative Lincoln, his face bearing the weight of war.

This same series produced dozens of CDV variations, each emphasizing different aspects of Lincoln’s character – his determination, wisdom, and his ordinary humanity. These interpretations of presidential imagery etched his memory in time just after the assassination, have been reproduced in every decade since, and still shape our national memory today.

Consider how presidential postcards – those humble, democratic pieces of correspondence – have both reflected and shaped our understanding of presidential perspective and leadership. Looking at postcard collections from presidential libraries, let’s explore how these portable portraits reveal how certain leaders viewed the world and made decisions.

Memory Making in Presidential Libraries

The modern presidential library system began in 1939 when Franklin Roosevelt donated his papers to the federal government, establishing a revolutionary model for preserving presidential legacy. Before this, presidential papers were considered private property, often scattered, sold, or lost to history. Roosevelt’s innovation created a systematic approach to presidential preservation that transformed how Americans access their presidential past.

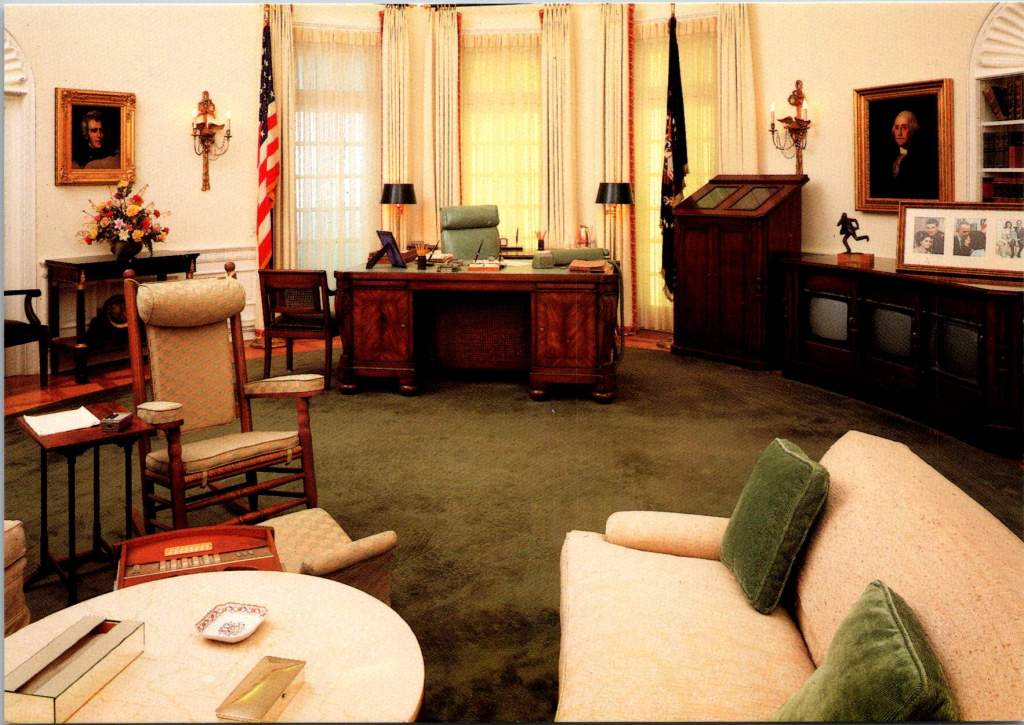

Today, fifteen presidential libraries, administered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), serve multiple functions: archive, museum, research center, and public education facility. Each library manages large collections of documents, photographs, and artifacts, while their museums and visitor centers help interpret presidential legacies for millions annually.

These institutions also play a crucial role in postcard production and distribution. Their gift shops serve as primary retail outlets, while their archivists and curators help ensure historical accuracy in commemorative imagery. Tensions between history, educational mission, and commercial viability shape how presidential memory is packaged and sold.

Business of Memory

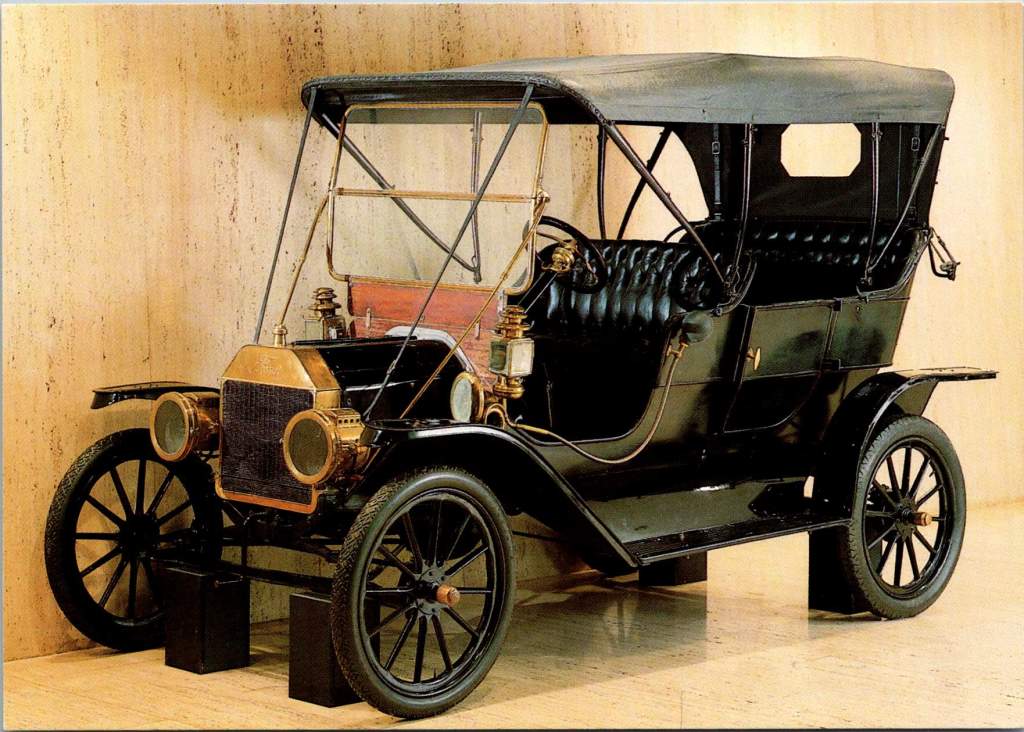

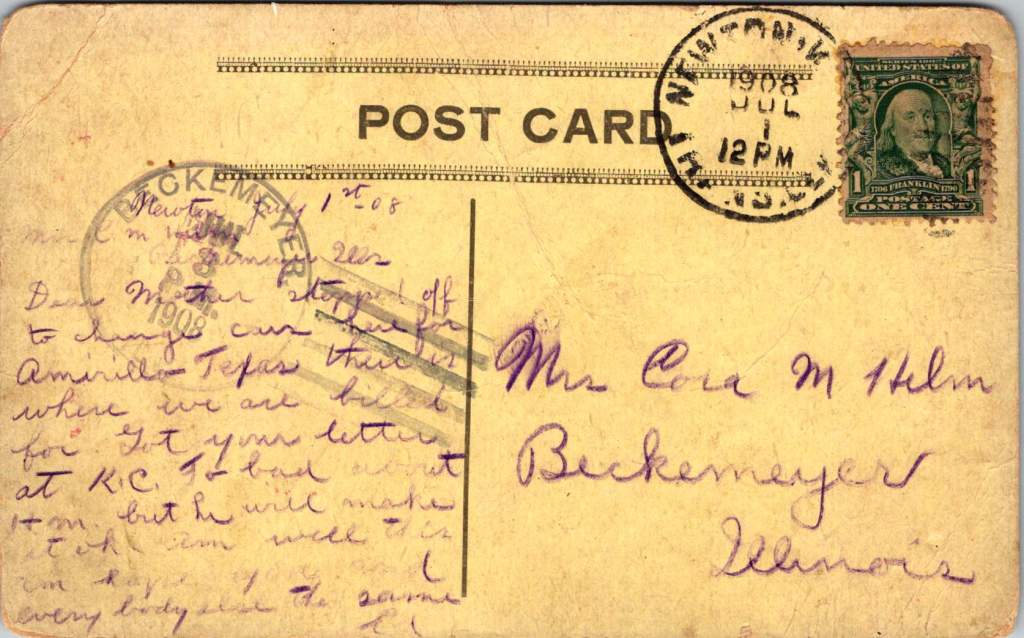

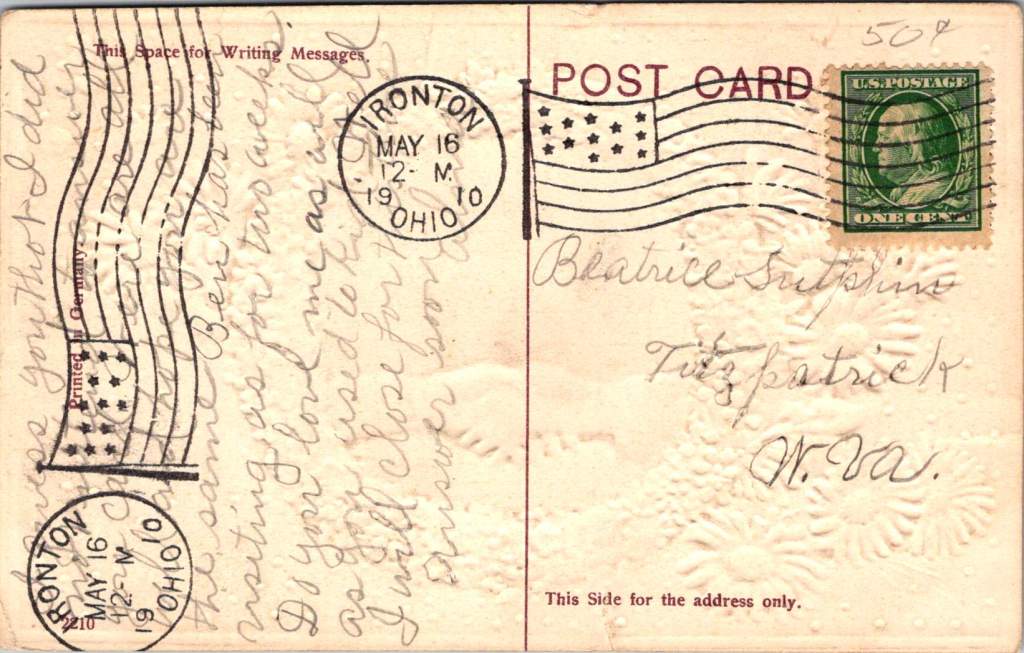

The story of presidential postcards is also the story of how American trades shape historical memory. In the late 19th century, innovations in printing technology coincided with the rise of mass tourism and the establishment of the postal service’s penny postcard rate. Companies like Curt Teich & Co. and the Detroit Publishing Company recognized an opportunity, creating catalogs of presidential imagery that would help standardize how Americans remember their leaders.

The economics were compelling: postcards could be produced for less than a cent, sold for 3-5 cents, and resold by retailers for 5-10 cents. This accessibility meant that average Americans could own and share pieces of presidential history. Later, the Presidential Libraries, the Smithsonian, and the National Park Service would become major distribution points, creating a government-private partnership in historical memory that continues today.

Postcard Power

Before diving into specific presidents, let’s remember why postcards matter. Unlike formal portraits or imposing statuary, postcards serve as intimate, portable connections to our leaders. Their very format – combining image with personal message, sold inexpensively and shared widely – makes them unique vehicles for democratic memory-making.

Consider the contrast: The Lincoln Memorial presents the 16th president as a marble deity, remote and perfect. But, period CDVs showed him in numerous human moments: reviewing troops, visiting battlefields, and playing with his sons. These cards, sold for pennies and passed hand to hand, helped Americans see their wartime leader as both extraordinary and approachable.

Lincoln: The Moral Realist

The Gardner series of photographs reveals Lincoln’s moral realist perspective in subtle ways. In one popular version, Lincoln’s gaze is directed slightly upward, suggesting moral vision, while his worn face acknowledges harsh realities. This duality perfectly captured Lincoln’s ability to hold fast to moral principles while grappling with very real human suffering.

Another influential series showed Lincoln visiting the Antietam battlefield. These cards, first published during the war and reprinted for decades after, highlighted his hands-on leadership style. One image shows him speaking with wounded soldiers from both sides – a visual representation of his “malice toward none” philosophy.

Theodore Roosevelt: The Progressive Naturalist

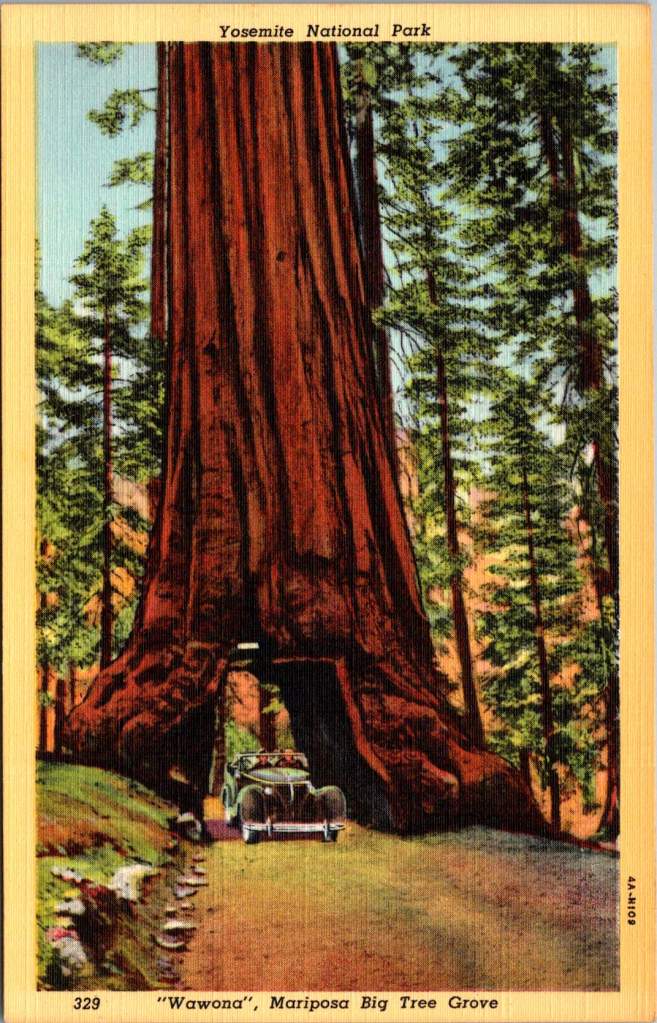

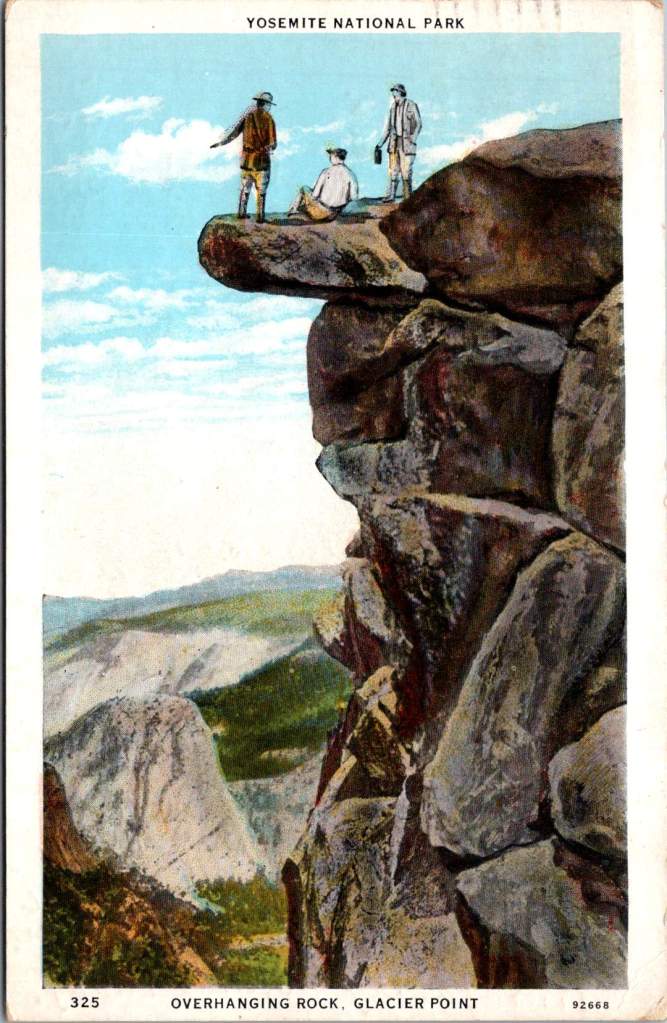

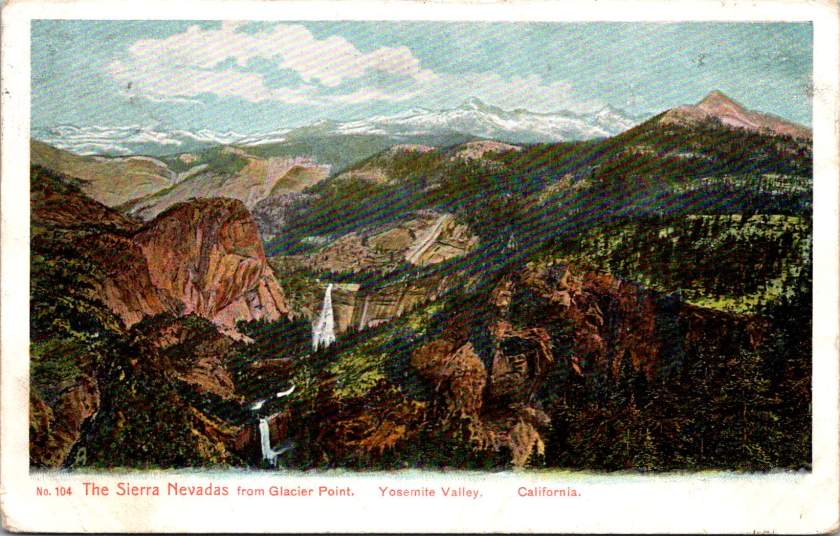

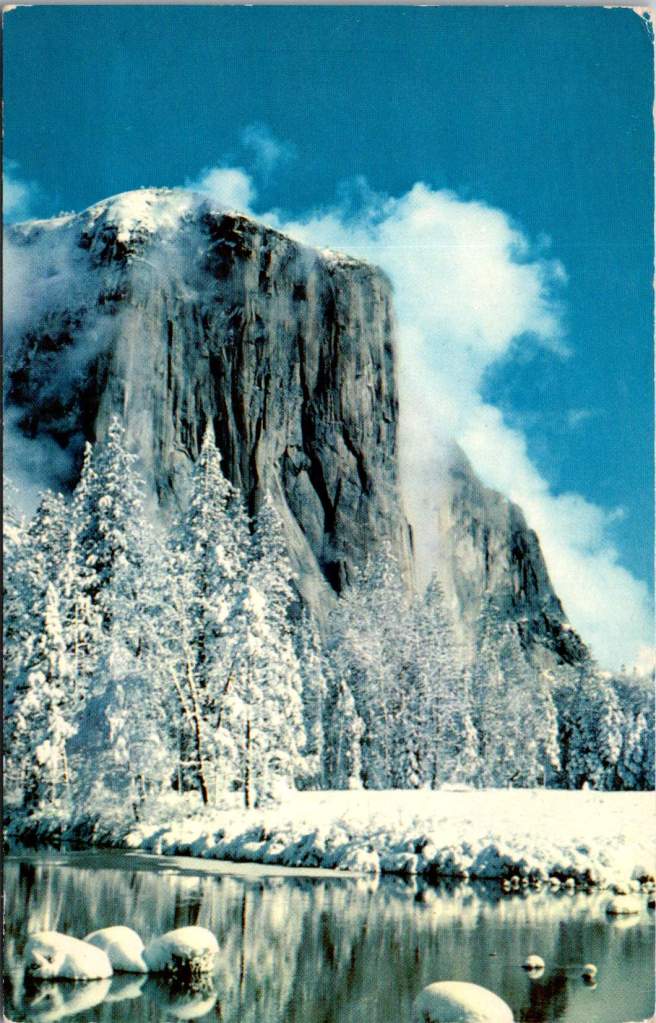

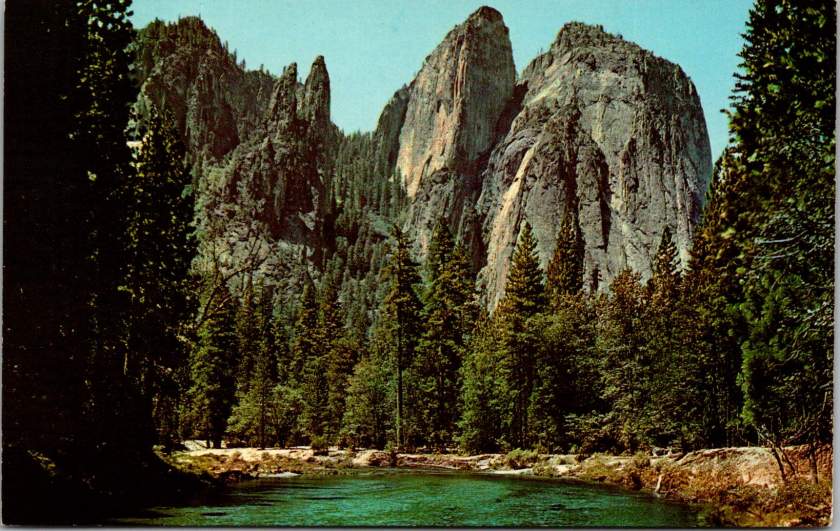

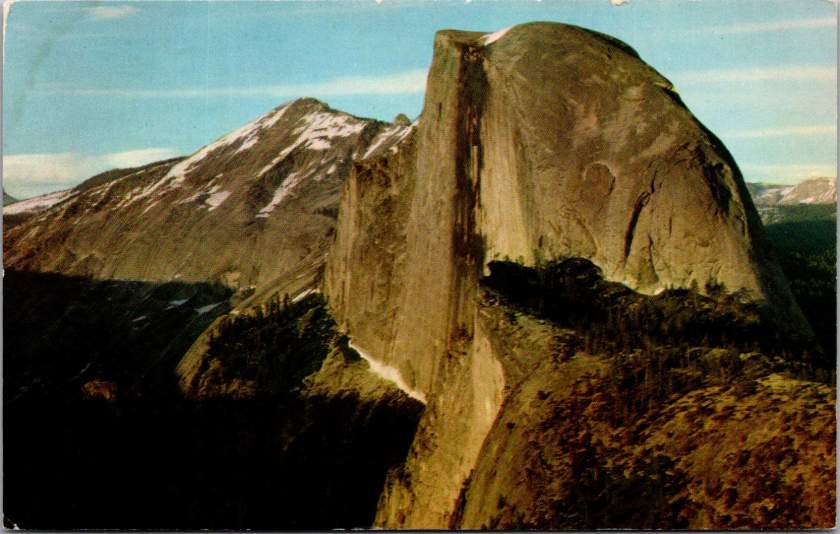

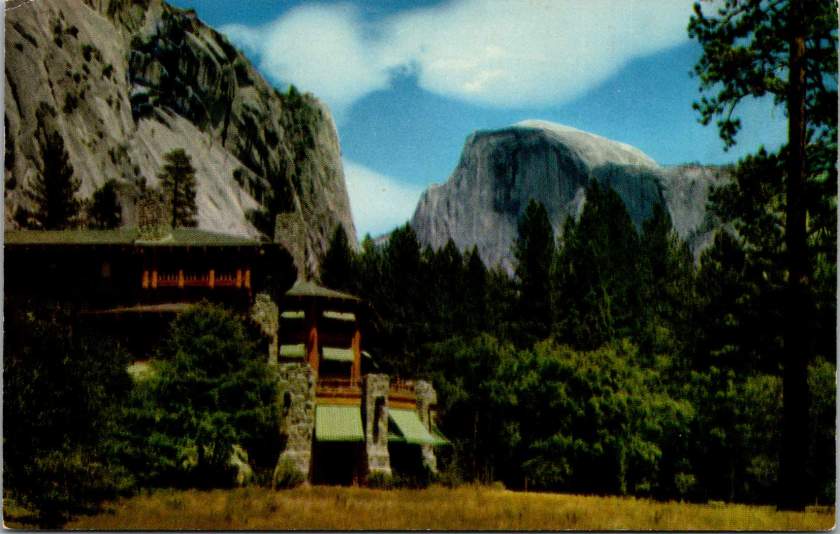

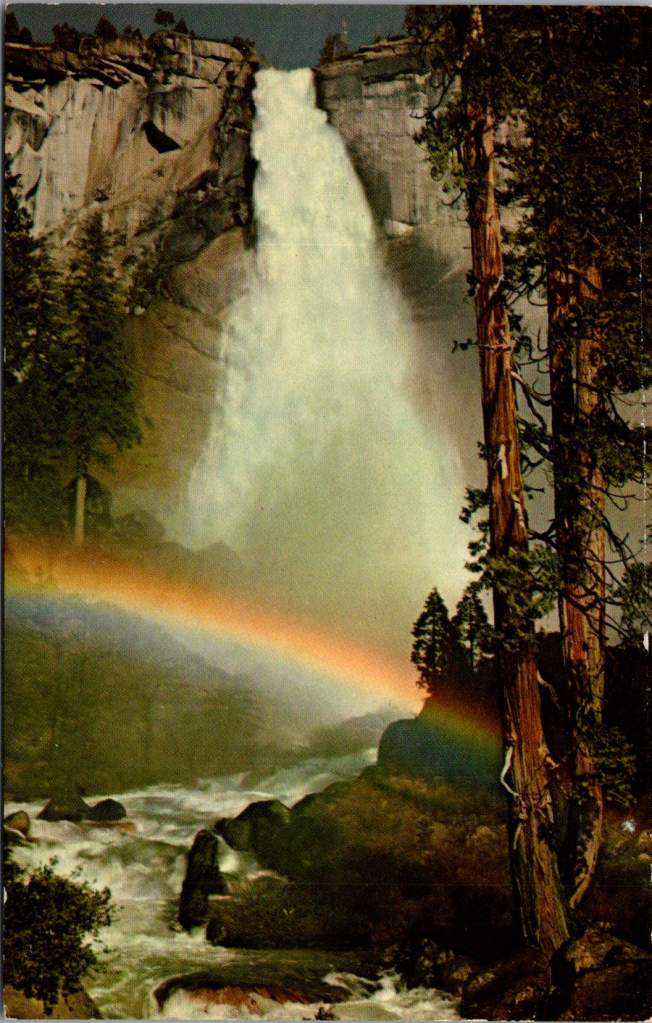

The postcards of Teddy Roosevelt present a striking contrast. The Detroit Publishing Company’s Yosemite series showed him with naturalist John Muir in various outdoor settings, emphasizing his connection to nature and physical vigor. These images perfectly aligned with his naturalistic-progressive worldview, which saw human advancement as part of natural evolution.

Perhaps most revealing were the Rough Rider postcards, mass-produced during and after his presidency. These action-oriented images showed Roosevelt leading charges, planning strategy, and bonding with his men. They captured his belief in the power of human will to shape both nature and society – a core tenet of his progressive philosophy.

Franklin Roosevelt: The Pragmatic Experimenter

FDR’s postcard imagery evolved significantly during his presidency, reflecting both personal and national transformation. Early cards showed him standing at podiums, emphasizing traditional presidential authority. But as the Depression deepened, a new style emerged.

Fireside Chat postcards, first released in 1933, showed Roosevelt in intimate settings, explaining complex policies to average Americans. These images matched the pragmatic instrumentalism they heard on the radio – his belief that truth and reality were tied to practical situations more than abstract principles.

The photographs from Warm Springs deserve special mention. While official imagery generally hid Roosevelt’s disability, these postcards showed him in the therapeutic pools, working to strengthen his legs. They humanized him while demonstrating his experimental, solution-oriented approach to problems, both personal and political.

Kennedy: The Dynamic Optimist

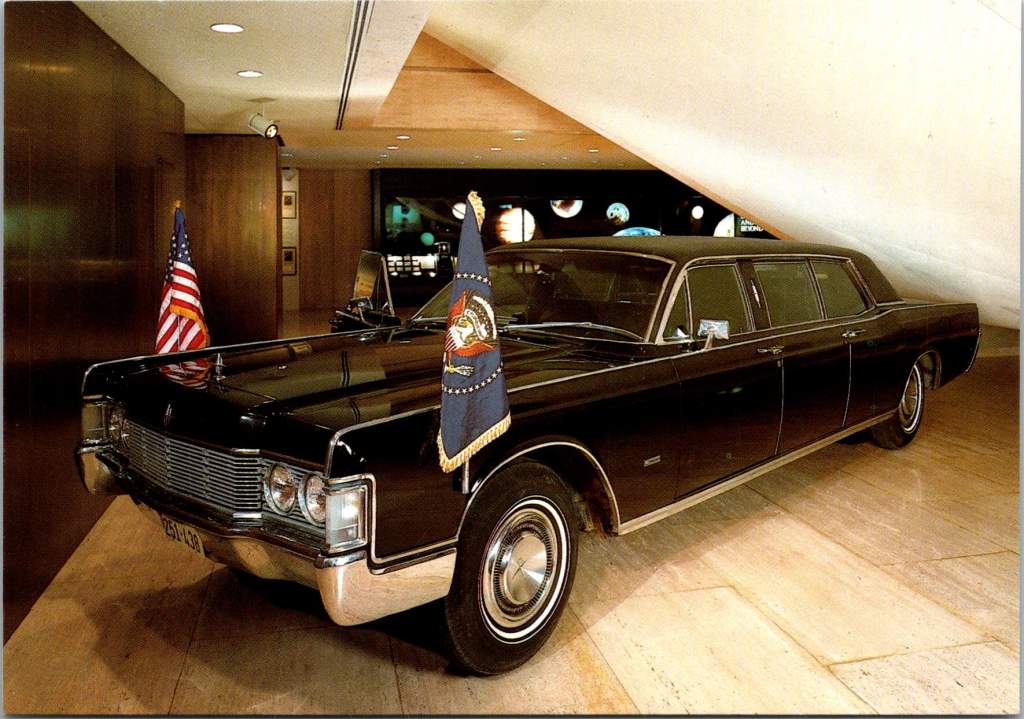

The Kennedy era revolutionized presidential imagery. Color photos from Hyannis Port show the president sailing or playing with his children, emphasizing youth and vitality. But more telling were the Space Race postcards, which showed Kennedy studying rocket models or meeting with astronauts. These captured his perspective of historical dynamism – his belief that reality itself was expandable through human initiative and technological advancement.

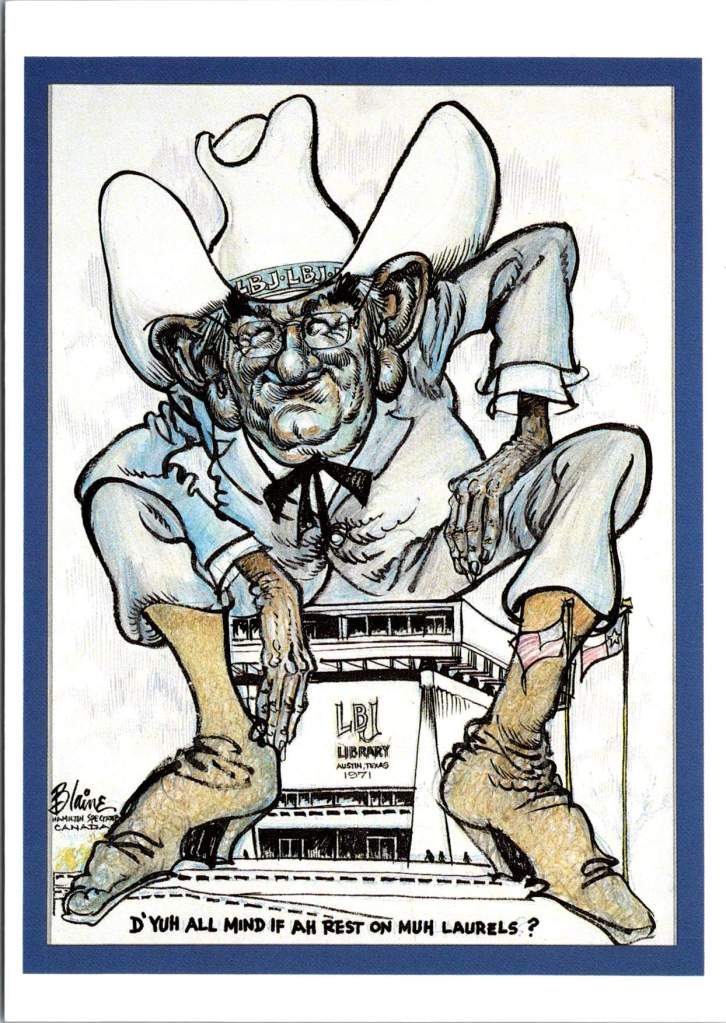

LBJ: Larger than Life

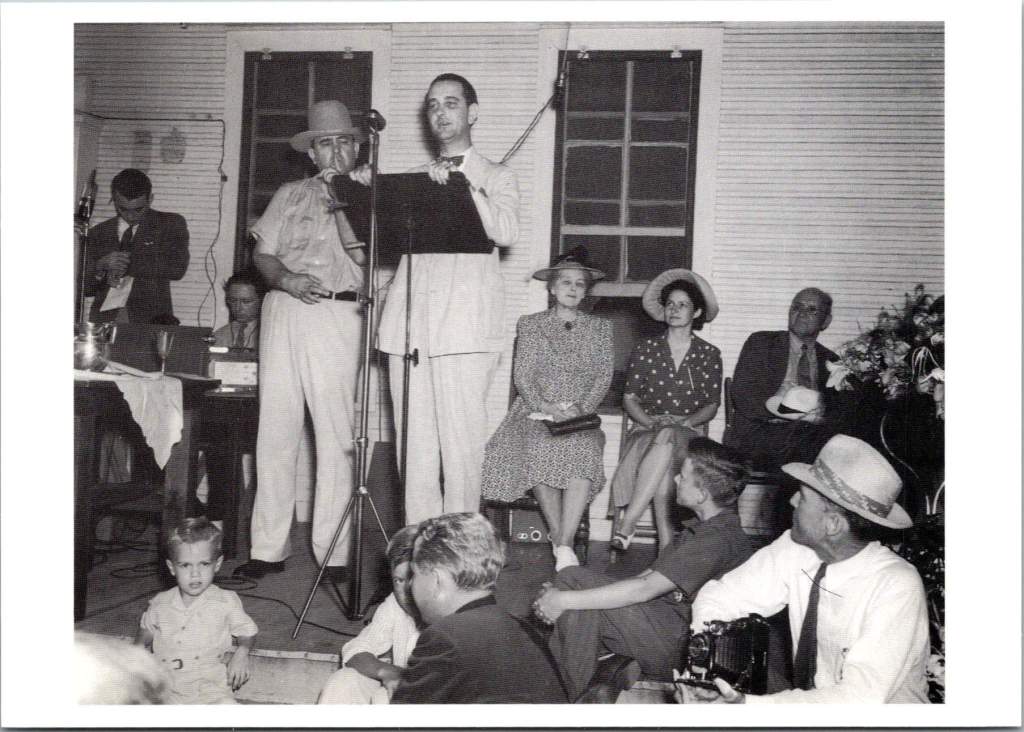

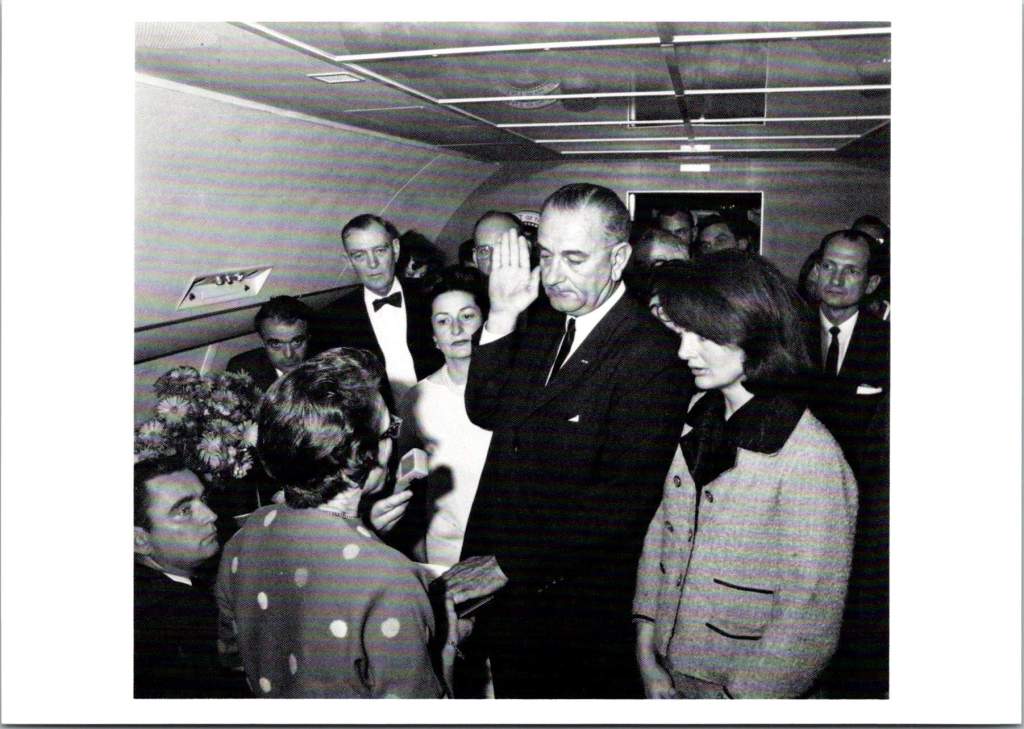

The LBJ Library’s postcard collection reveals another perspective entirely, showing Johnson’s complex relationship with power and persuasion. The collection captures Johnson in intimate conversations with civil rights leaders and in passionate speeches about poverty, reflecting his hands-on, domineering approach to domestic reform.

Carter: The Moral Engineer

Jimmy Carter’s postcard imagery often puzzled publishers. How to capture a president who combined technical expertise with moral conviction? The “Carter and Farmers” card showed him inspecting crops, and another shows him in front of solar panels on the White House roof. These images captured his unique moral-engineering perspective – his belief that problems required both technical solutions and ethical frameworks.

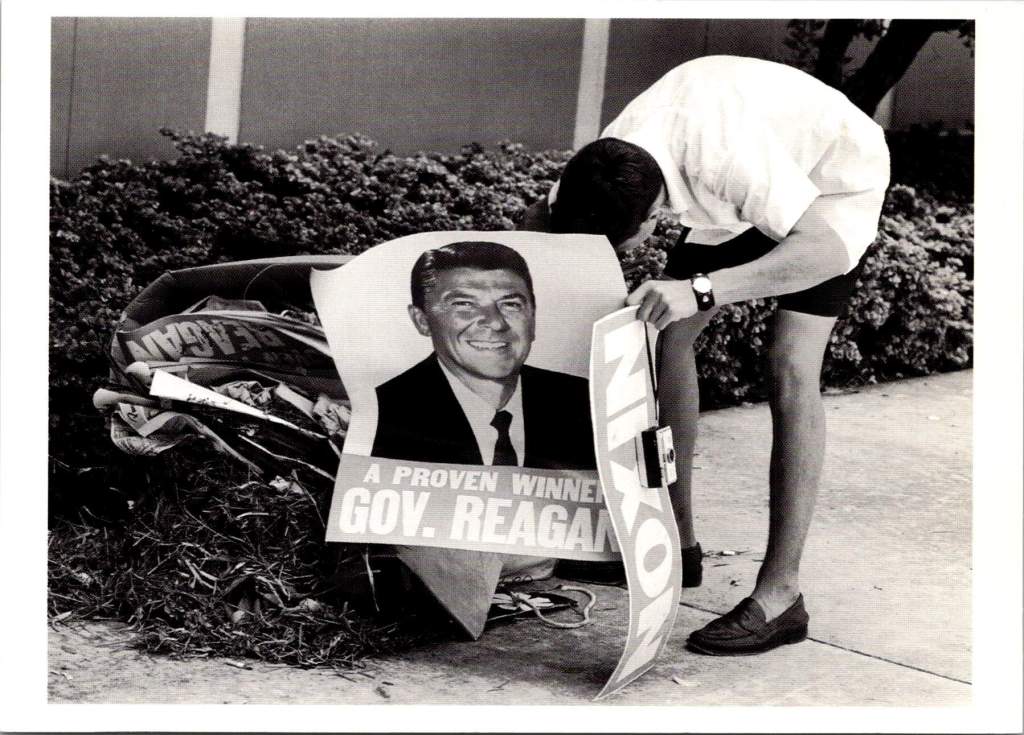

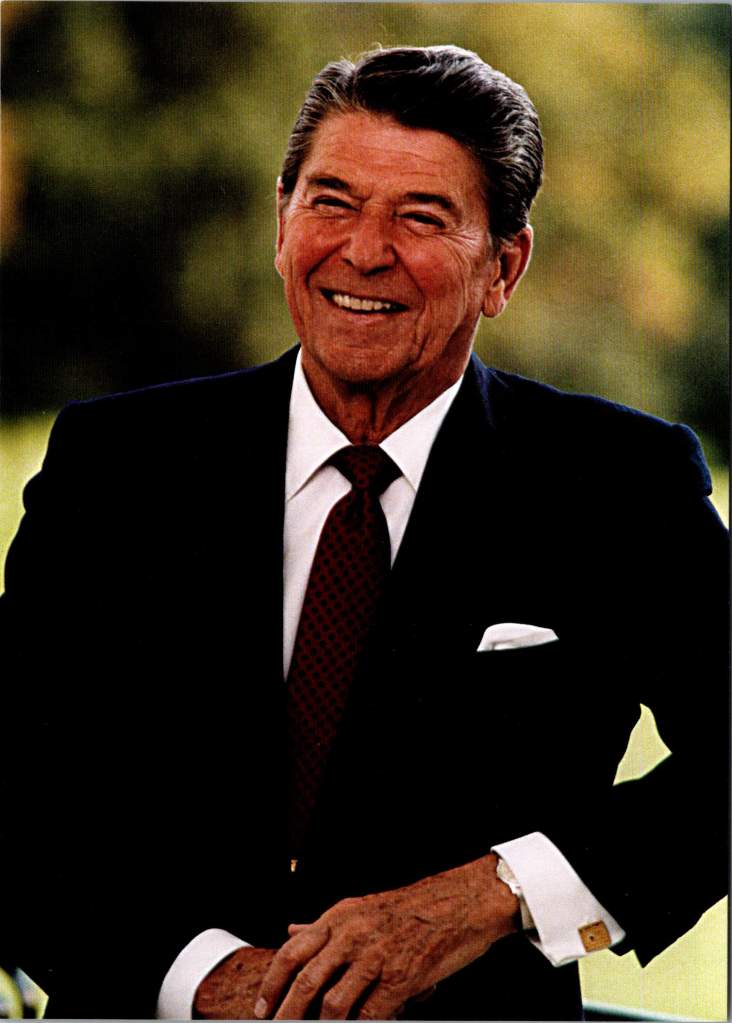

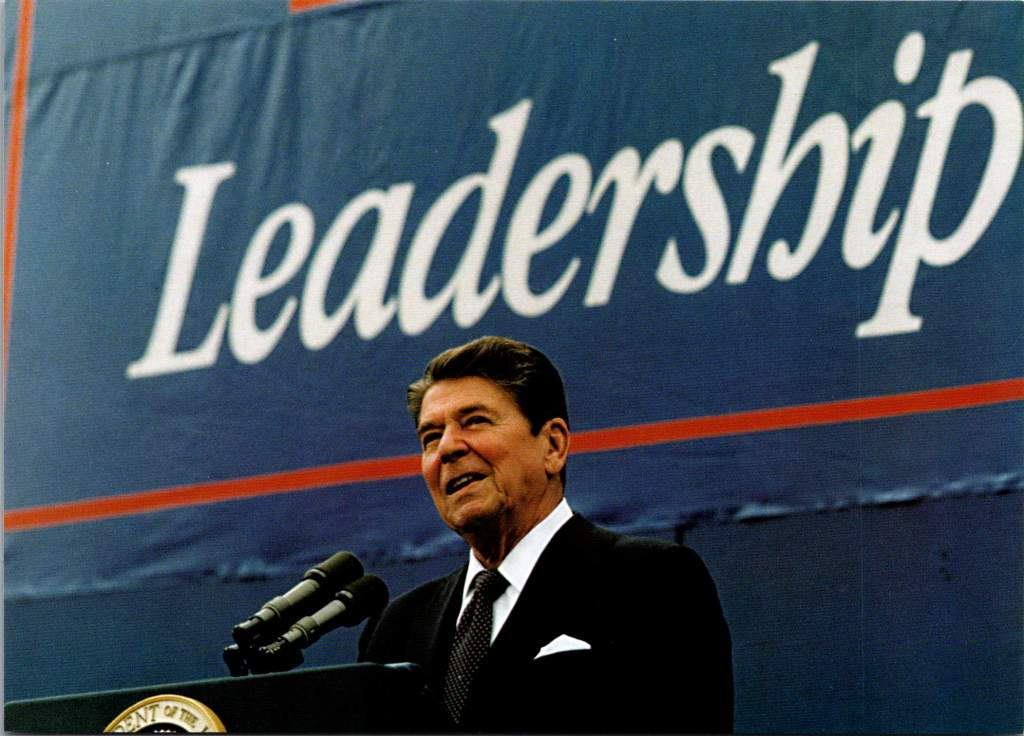

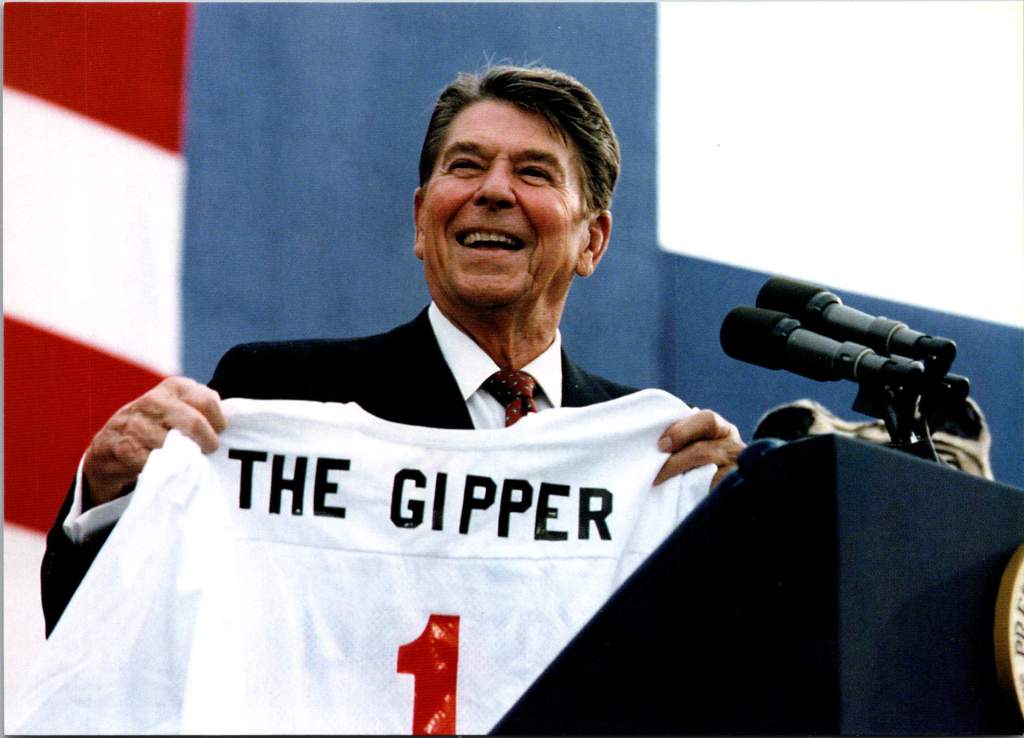

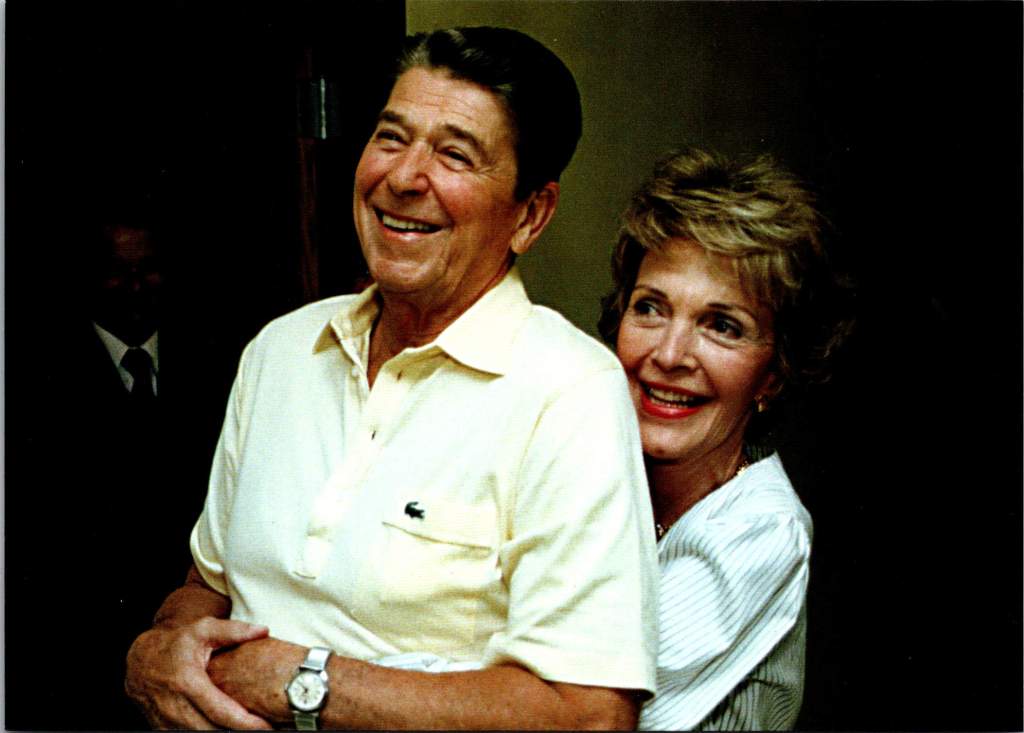

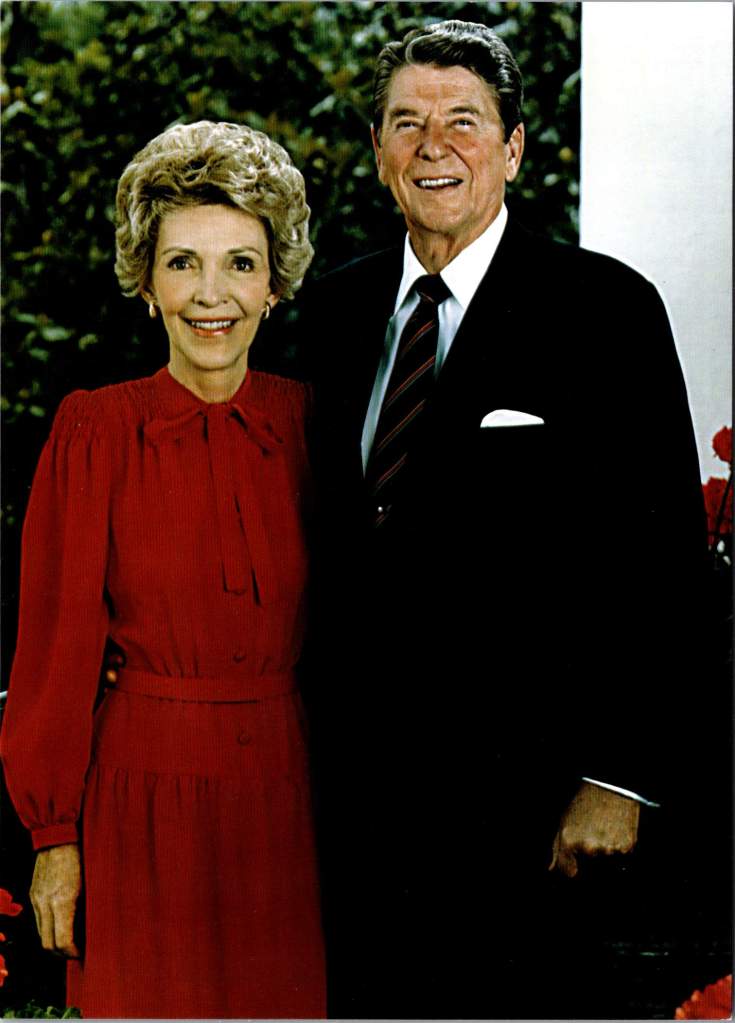

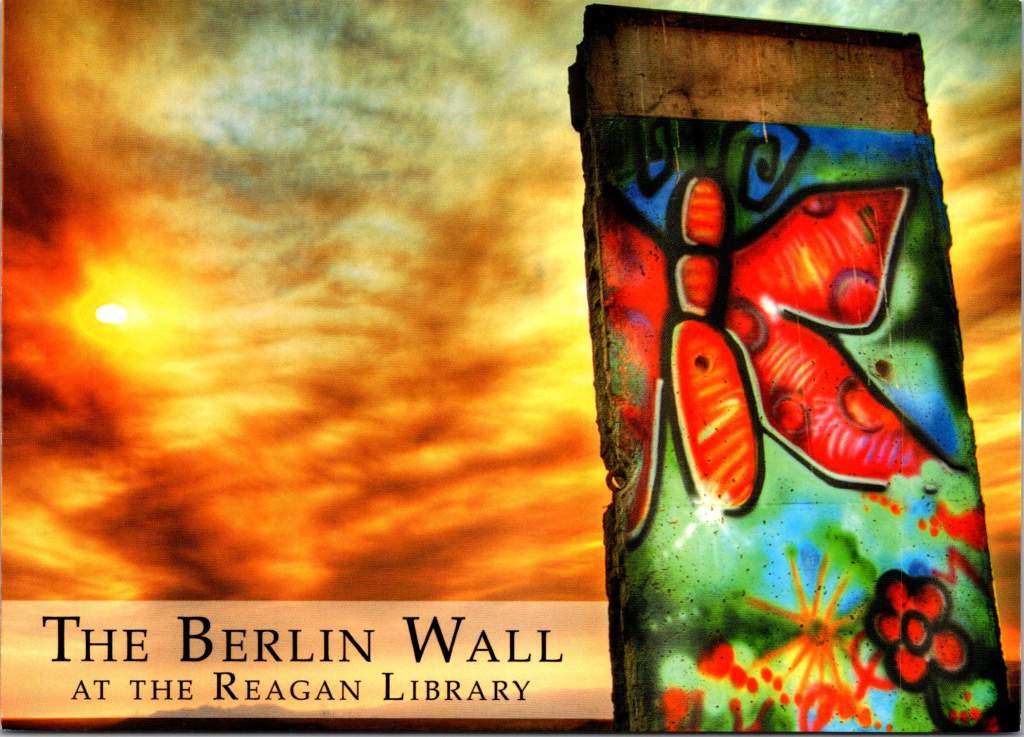

Reagan: The Moral Dualist

The Reagan Library’s postcard collections reflect his clear moral dualist worldview. The famous Brandenburg Gate series shows Reagan from multiple angles as he challenges Gorbachev to “tear down this wall.” These images emphasize his belief in clear moral absolutes – freedom versus tyranny, good versus evil.

Reagan’s unique gift for communication amplified the impact of these postcards. His ability to speak in accessible language while conveying profound ideas meant that the images resonated deeply with the public. When he spoke of America as a “shining city on a hill” or called the Soviet Union an “evil empire,” these phrases became powerful captions for postcard imagery, blending visual and verbal memory in the public mind.

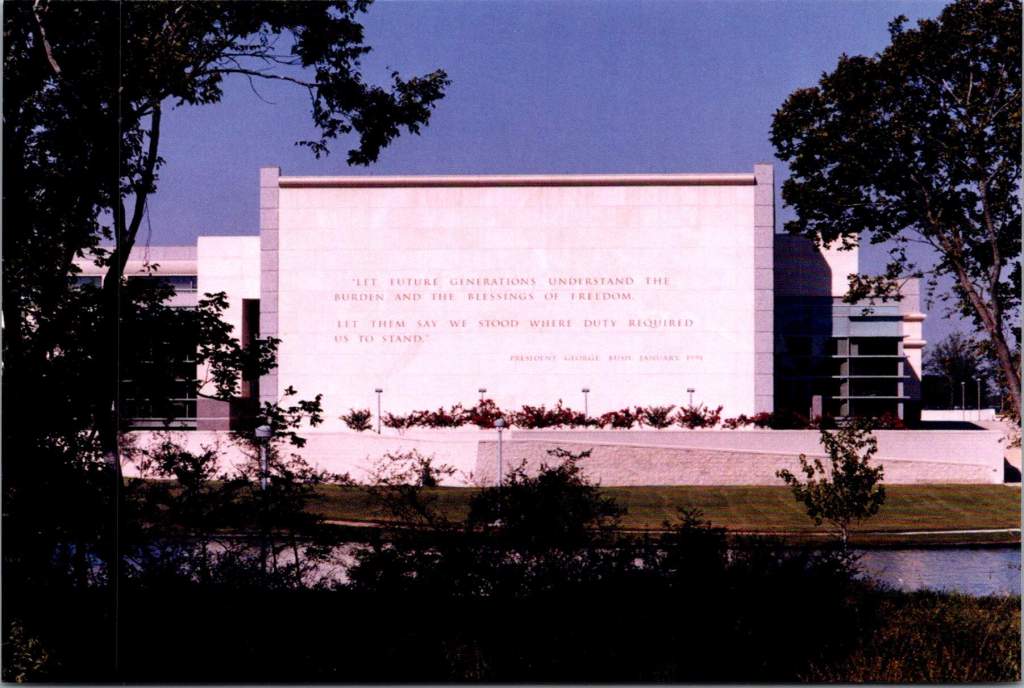

George H. W. Bush – Institutional Security

The George H.W. Bush Library’s postcards emphasize his diplomatic achievements, particularly during the Gulf War. These images often show Bush in military context and related to large institutions. The contrast with Reagan’s more populist imagery is striking – where Reagan is clearly a personality, Bush’s postcards frequently make the man matter less than the magnitude of his role.

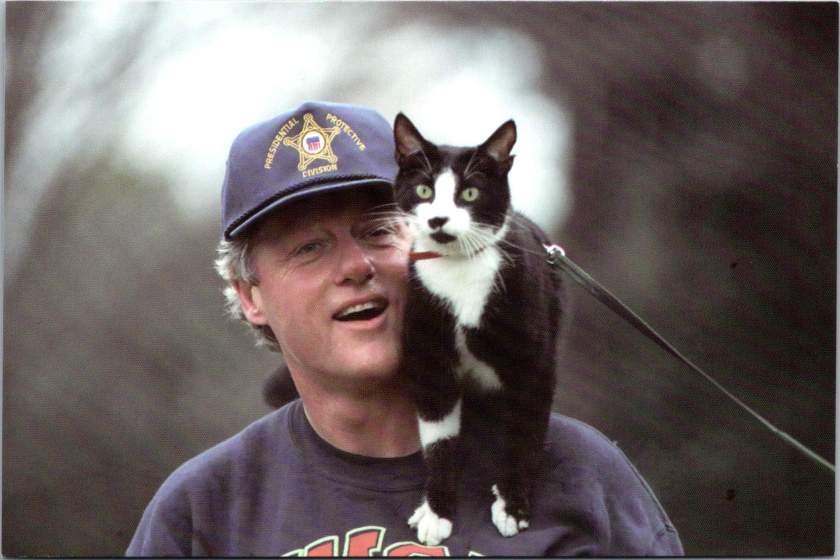

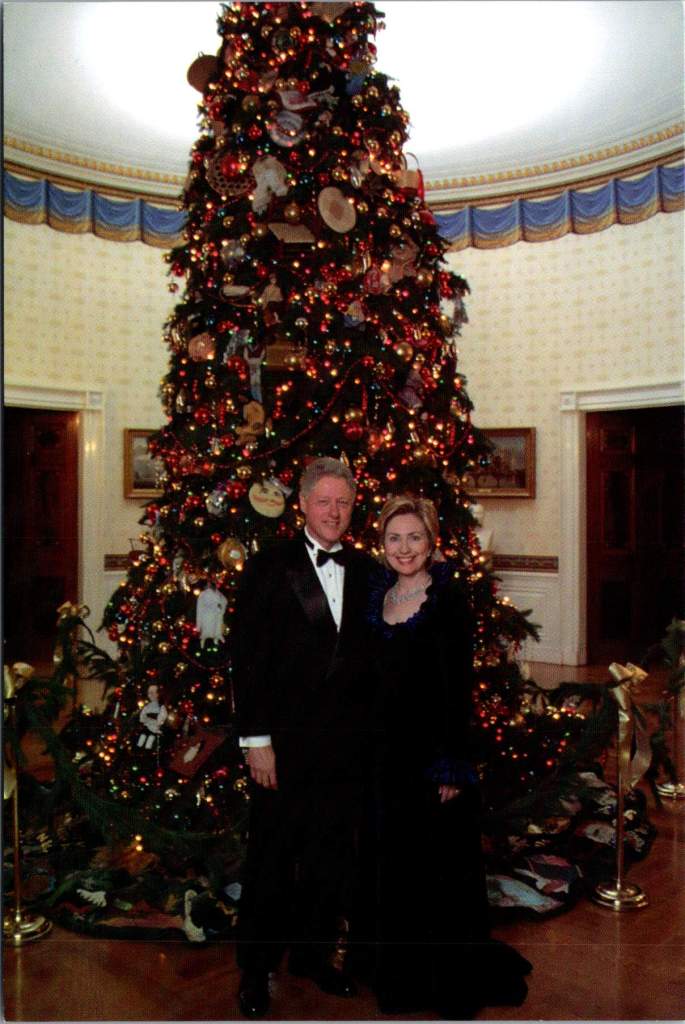

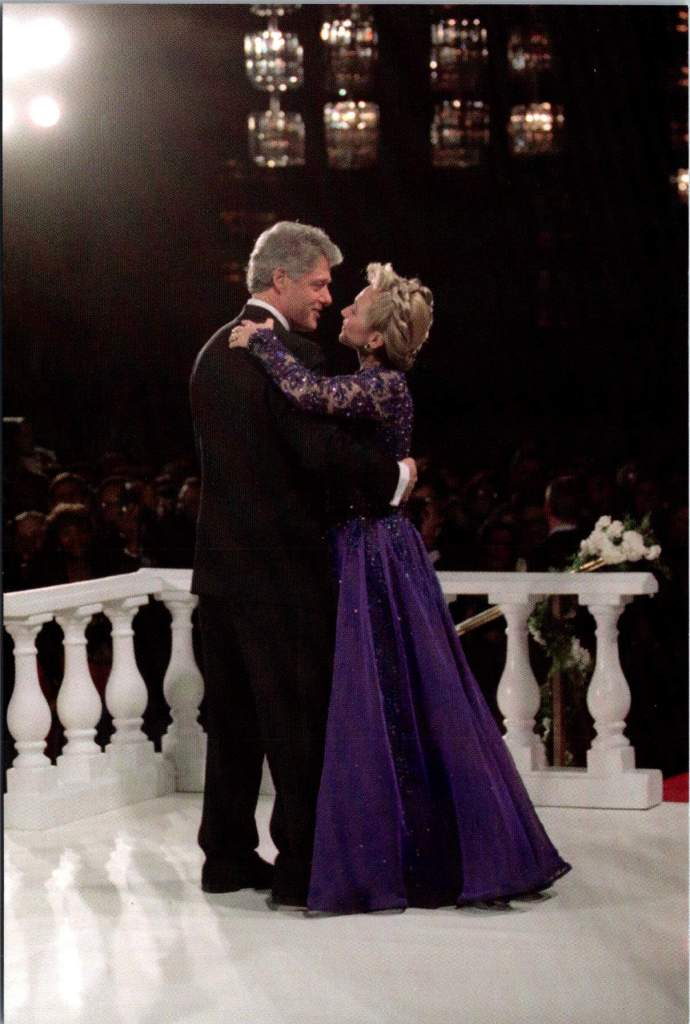

Clinton’s Casual Comport

The Clinton Library’s postcard collection breaks new ground in presidential imagery, showing Clinton with his daughter Chelsea, playing with Socks the cat, and capturing his forward-looking optimism in the post-Soviet era. These images demonstrate Clinton’s ability to relate to his constituents in casual terms, mirroring what Reagan had done with conservative principles.

The Persistence of Perspective

What emerges from this look at presidential postcards is the remarkable consistency with which each President projects his image in keeping with his worldview. Whether facing economic crisis, cold war, or civil war, these presidents tended to approach problems through a lens shaped by life circumstances as much as political philosophy. Lincoln’s moral realism helped him navigate both slavery and secession. FDR’s pragmatic experimentalism served him in depression and disability. Reagan’s moral dualism shaped his approach to both domestic policy and Soviet relations.

Yet the postcards reveal the human dimension of leadership, too. Through these small, shared images, Americans see their leaders as both exceptional and relatable. The very format of postcards – democratic, portable, personal – helps bridge the gap between presidential perspective and public understanding.

Presidential Perspective and Democratic Memory

Understanding presidential perspective remains crucial today. How leaders view reality shapes how they define problems, evaluate solutions, and make decisions. The enduring power of postcards lies in their ability to capture and communicate these perspectives in accessible ways.

Presidential postcards serve as more than souvenirs. They are vehicles of democratic memory, helping each generation understand not just what their leaders did, but who they were and how they thought. As we face contemporary challenges, these historical perspectives – preserved and transmitted through humble postcards – offer valuable insights into the relationship between worldview and leadership.

Look closer the next time you are in a museum shop or visitors center. In those mass-produced images lie clues to how our leaders view the world – and how they helped Americans see it too. Perspective is about how we view problems, and also how we view ourselves as a nation and a people.