In the Amazon rainforest, vegetation thrives in countless green hues, symbolizing life’s abundance. Yet in Western art, sickly green often signifies death and corruption. How can one color embody such opposed concepts? This tension—between green as vitality and green as decay—forms the central paradox in humanity’s relationship with this enigmatic tertiary hue.

Green occupies a unique position in our visual lexicon. It bridges the cool tranquility of blue and the energetic warmth of yellow. This intermediate status perhaps explains its dual nature—a color of balance that simultaneously contains opposing forces.

Toxic Chemistry: From Wallpaper to Printer’s Ink

The story of green pigment drips with poison. For centuries, the most vibrant greens came from copper arsenite, creating infamous “Paris Green” that adorned Victorian wallpapers and allegedly contributed to Napoleon’s death through arsenic poisoning. Scheele’s Green, developed in the late 18th century, released deadly arsenic gas when dampened. Victorian walls literally “breathed” death through their verdant decorations.

This toxic history highlights a contradiction: the color most associated with natural life proved historically among the most unnatural and deadly to produce. Nineteenth century painters risked chronic arsenic poisoning for the perfect emerald tone.

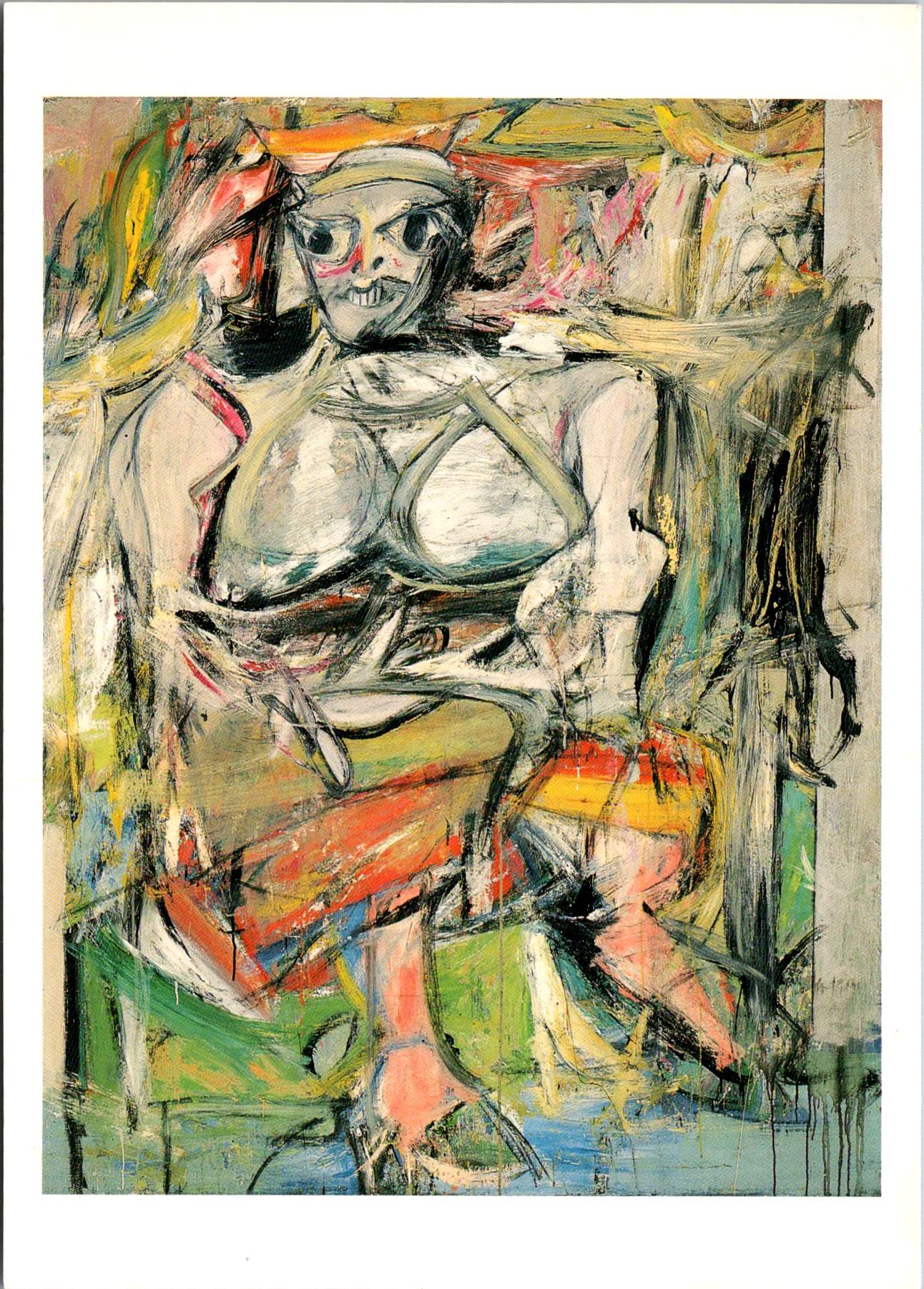

Printing technology reveals another dimension of green’s complex nature. Traditional lithography treated green as a distinct entity. Master printers blended pigments to create precise green tones before applying them to printing stones. Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographic posters featured carefully formulated green inks to capture the absinthe-tinged atmosphere of Parisian nightlife.

Modern CMYK printing creates green through optical mixing instead. Green isn’t a primary ink but emerges from combining yellow and cyan dots in precise patterns. This technique echoes Neo-Impressionist pointillism, where artists like Seurat placed distinct color dots side by side, allowing viewers’ eyes to blend them into a third color. A magazine’s solid green leaf reveals itself as an array of cyan and yellow dots under magnification.

This absence-made-present quality of green in modern printing mirrors its philosophical status: green exists at boundaries between colors and concepts. While our eyes perceive green as distinct (wavelength 495-570 nanometers), the printing process creates it through subtraction and combination—an illusion constructed from non-green components.

Green Means Go

One of green’s most recognized meanings emerged in the late 19th century with traffic signals. Green indicating “go” now transcends language barriers worldwide.

This standardization began with British railway signals in the 1830s, borrowing from maritime tradition where green lights indicated starboard. The first traffic light with red and green signals appeared outside London’s Parliament in 1868, predating automobiles. Gas-lit red and green lamps operated manually by police officers guided horse-drawn carriages.

The choice wasn’t arbitrary but built on psychological associations. Green’s connection to safety likely stems from evolutionary biology—natural green environments generally signal available food and absence of danger.

The 1949 Geneva Protocol formalized green’s role in traffic systems globally. Today, from Tokyo’s sophisticated networks to remote Indian intersections, green universally permits passage. This standardization extends to pedestrian crossings, airport runways, and maritime navigation.

This creates a fascinating contradiction: the color most associated with nature now primarily serves an urban, technological function. Times Square’s green traffic light and the Moscow Metro’s green signal represent perhaps green’s most recognized meaning—entirely disconnected from the natural world that gave the color its original significance.

Green’s role as “go” permeates language. “Getting the green light” implies permission and opportunity. Business reports use green to indicate positive metrics. This association with forward movement and progress creates another layer of meaning for this multivalent color.

Envy and Avarice

Perhaps nowhere is green’s paradoxical nature more evident than in its associations with money and envy. Shakespeare’s description of jealousy as “the green-eyed monster” in Othello connects the color to one of humanity’s most corrosive emotions. This association may stem from physiology—intense jealousy can produce a pallid, greenish complexion due to blood flow changes—the body manifesting emotion through color.

Currency, particularly American dollars, has become synonymous with green. “Greenback” entered common parlance as a synonym for money. The decision to print American currency in green stemmed from practical concerns—green ink resisted photographic counterfeiting and remained chemically stable. This pragmatic choice evolved into a powerful cultural symbol representing both opportunity and excess, freedom and materialism.

Medieval European art portrayed avarice through green-tinted figures clutching moneybags. Giotto’s 14th-century fresco “The Seven Deadly Sins” in Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel depicts Avarice with greenish skin, visually linking the color to unnatural desire for wealth.

Green Flags

Green features prominently in approximately 40 national flags, each instance carrying distinct cultural significance. Brazil’s verdant background represents the Amazon rainforest, directly linking national identity to landscape. Saudi Arabia’s entirely green flag connects the color to Islamic associations with paradise and the Prophet Muhammad.

Nigeria’s vertical bands with green on either side symbolize natural wealth and agricultural resources. Similarly, Pakistan’s predominantly green flag represents both Islamic heritage and agricultural prosperity. In Ireland, green in the tricolor evokes both the verdant landscape (“Emerald Isle”) and Catholic nationalist tradition.

Portugal’s green carries revolutionary significance, representing hope following the Republican revolution of 1910. The Italian tricolor uses green to complete its representation of the natural landscape—the Alps’ snow, Mount Etna’s lava, and the country’s fertile plains.

Green in many African nations’ flags—including Senegal, Cameroon, and Zimbabwe—often represents natural resources and agricultural wealth, while simultaneously nodding to Pan-African colors inspired by Ethiopia’s flag.

These varied uses in national symbolism show how green serves as canvas for diverse values: religious devotion, natural abundance, revolutionary hope, and cultural heritage—sometimes simultaneously within the same emblem.

Green Spaces

The concept of “green space” contains inherent tension. In urban planning, green spaces represent deliberate human interventions—parks and conservation areas that preserve nature within developed landscapes. New York’s High Line transforms an abandoned railway into a linear park, while Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay creates futuristic “supertrees” blending technology and nature.

In Bali’s rice terraces, agricultural practice created one of the world’s most striking green landscapes. These centuries-old terraced fields follow hillside contours, representing harmony between human needs and natural topography that has become iconic in travel photography.

“Greenwashing” introduces another tension—the superficial application of environmental imagery to mask environmentally harmful practices. The color once simply representing nature now carries political dimensions, conscripted into debates about sustainability and corporate responsibility.

Beyond Growth

The “green economy” represents perhaps the most significant modern appropriation of the color, embodying tension between environmental sustainability and economic development. Traditionally seen as opposing forces, the green economy concept attempts reconciliation, suggesting an economic system generating prosperity without degrading ecological systems.

This reconciliation attempts to resolve fundamental tension in green’s symbolism. The color representing both verdant growth and corruption of excess now stands for an economic model decoupling prosperity from environmental harm.

Yet the green economy concept contains internal contradictions. Critics argue “green growth” often represents contradiction in terms—attempting to maintain unsustainable consumption through marginal efficiency improvements. This criticism spawned more radical conceptions, including the circular economy model.

The circular economy transcends the linear “take-make-dispose” industrial model to envision economic activity mimicking natural cycles. In nature, nothing wastes—one organism’s decomposition nourishes another. Fallen leaves decay into soil feeding the next generation. This cyclical pattern contrasts with the ever-upward arrow of traditional economic growth charts.

Inspired by natural systems, circular economy advocates like Ellen MacArthur envision products designed for disassembly and reuse, with materials continuously circulated rather than discarded. The bright green growth arrow transforms into a green regeneration circle—emblematic in recycling symbols worldwide.

This shift from growth-as-expansion to growth-as-renewal reimagines green’s economic symbolism. Finland’s forests, supplying timber under strict regeneration requirements, exemplify this approach—harvested trees always replanted, creating sustainable cycles rather than mere extraction. This forest management system models how economic activity can align with natural regeneration.

The Color of Paradox

Green remains the color of paradox—simultaneously natural and artificial, life-giving and toxic, calming and unsettling, signifying unfettered growth and mindful circularity. This duality explains its enduring fascination. Unlike primary colors with straightforward associations, green exists in in-between spaces—a tertiary tone refusing simple categorization.

From deadly Victorian pigments to digital screens, from Islamic tradition to environmental movements, from envious emotions to regenerative economics, green continues evolving while maintaining fundamental tensions. In all its tertiary complexity, green continues defining spaces where human creativity engages with fundamental forces of growth, change, and renewal.