In summer 1972, the United States Postal Service issued commemorative postcards that would become enduring symbols of national identity. These postcards, part of the Tourism Year of the Americas campaign, featured iconic destinations with restrained elegance—their two-color printing was both artistic and economical. As America stood at a cultural crossroads, this postcard set tells a familiar American story. More than five decades later, they reveal even more about how a nation sees itself.

Commemorative Moments

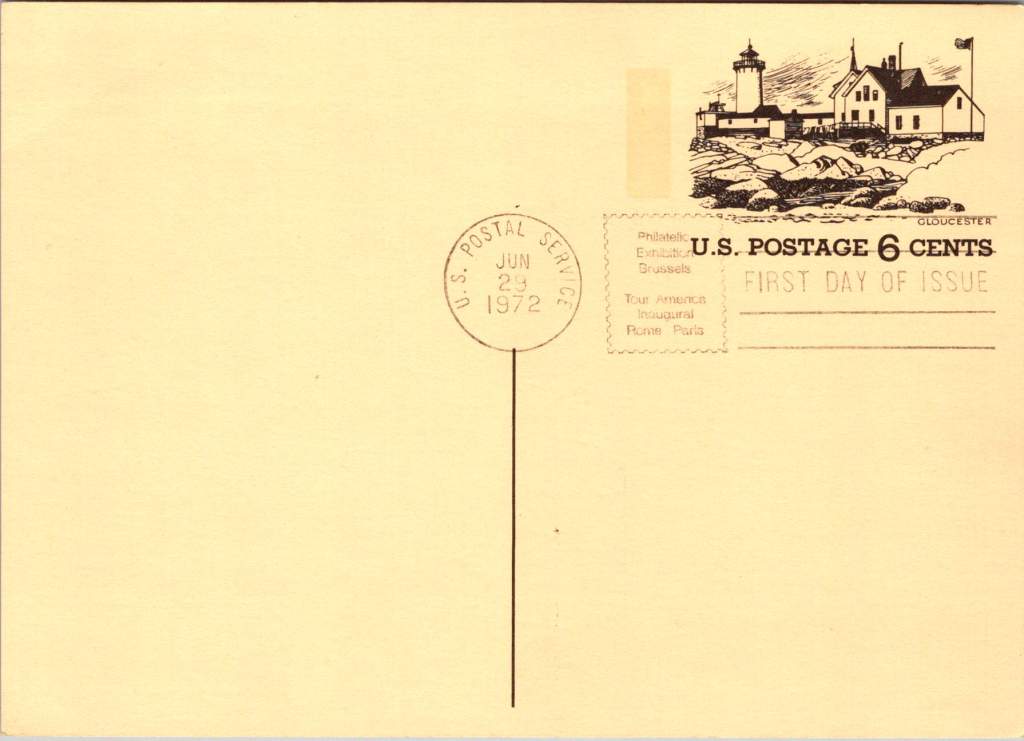

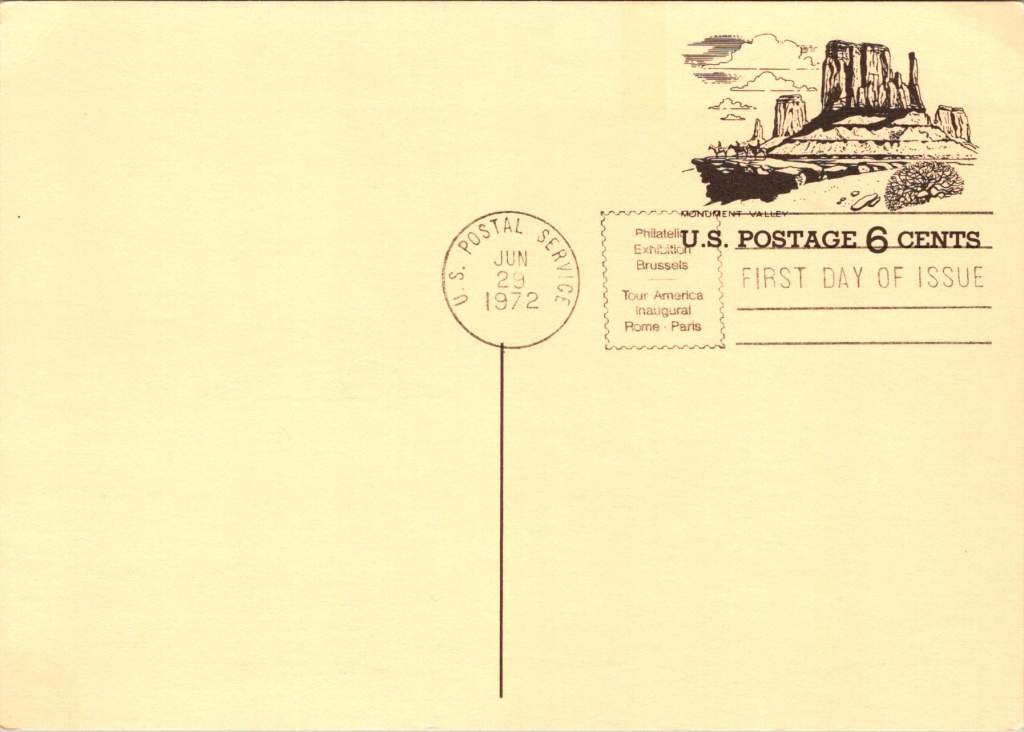

First Day of Issue cancellations mark a special moment in time, and signal that an item is expected to be collectible. The postcards were cancelled on June 29, 1972, bearing the commemorative text “Philatelic Exhibition Brussels” and “Tour America Inaugural Rome – Paris.” These international exhibitions promoted American tourism during the Cold War, when cultural diplomacy served as essential soft power.

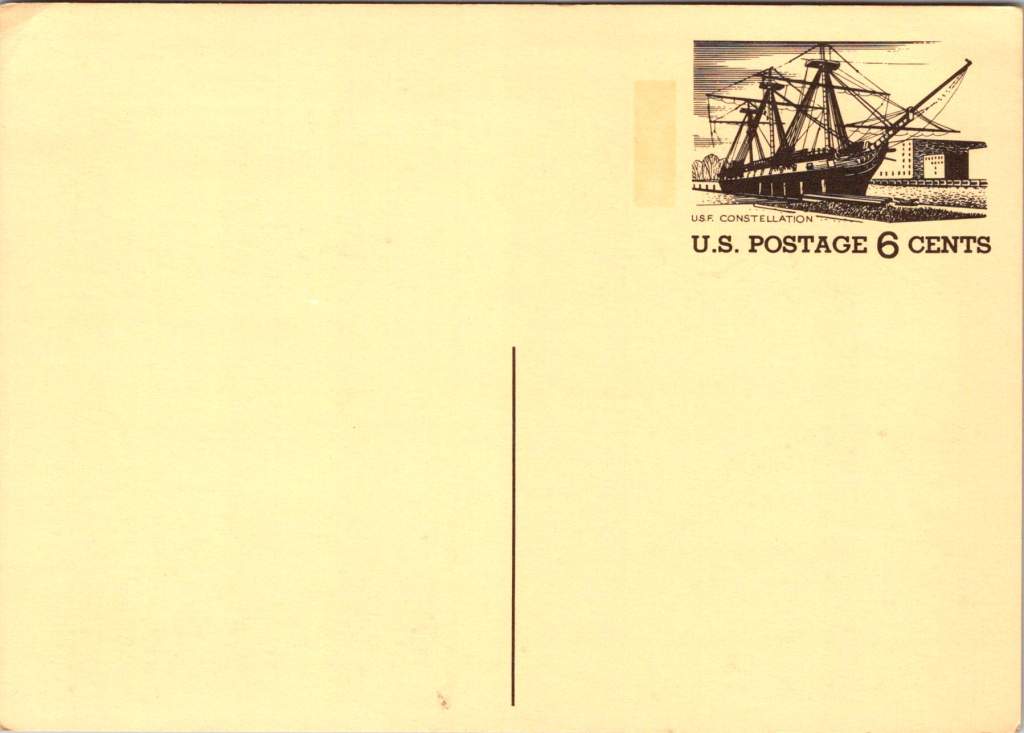

The carefully designed cancellation artwork includes USS Constellation (6¢), Gloucester (6¢), Monument Valley (6¢), and Niagara Falls (airmail 15¢). These rates reflected the newly reorganized United States Postal Service which had become its own entity the year prior. The 1972 Tourism Year of the Americas was an ambitious initiative from the new quasi-independent agency, emerging alongside Nixon’s opening to China and détente with the Soviet Union.

USS Constellation, the last sail-only warship built by the U.S. Navy (1853-1855), served as flagship of the Africa Squadron from 1859–1861. The ship captured three slave vessels, enabling liberation of 705 Africans. During the Civil War, Constellation deterred Confederate cruisers in the Mediterranean. The selection represented naval heritage and anti-slavery efforts, though it still centered the naval victory rather than those who gained freedom.

Niagara Falls has attracted visitors for 200 years, becoming the symbolic heart of American tourism. The 1883 Niagara Reservation became America’s first state park, influencing national park creation. Current visitor statistics show enduring appeal: 9.5 million tourists visited Niagara Falls State Park in 2023, with the region welcoming 12 million visitors yearly.

Monument Valley reflect the West’s central role in national identity by 1972, immortalized through Hollywood and environmentalism. Yet Monument Valley sits within Navajo Nation territory, while Grand Canyon encompasses land sacred to multiple tribes, including the Havasupai, whose reservation lies within park boundaries—reminders that park creation displaced Native communities.

Gloucester, America’s oldest seaport, sustained coastal communities for centuries. The lighthouse image evoked both practical maritime safety and romantic notions of New England’s rocky shores, while Gloucester’s working harbor embodied the intersection of heritage preservation and living tradition. By 1972, this historic fishing port faced the tension between maintaining its authentic maritime culture and adapting to tourism pressures—a challenge that made it a fitting symbol.

Artistic Vision

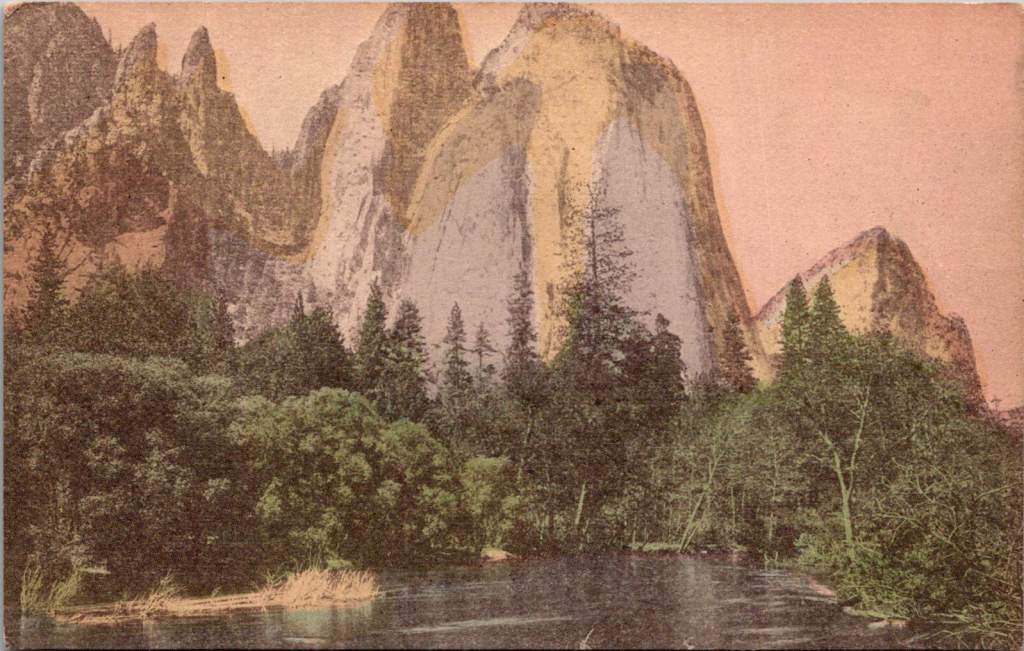

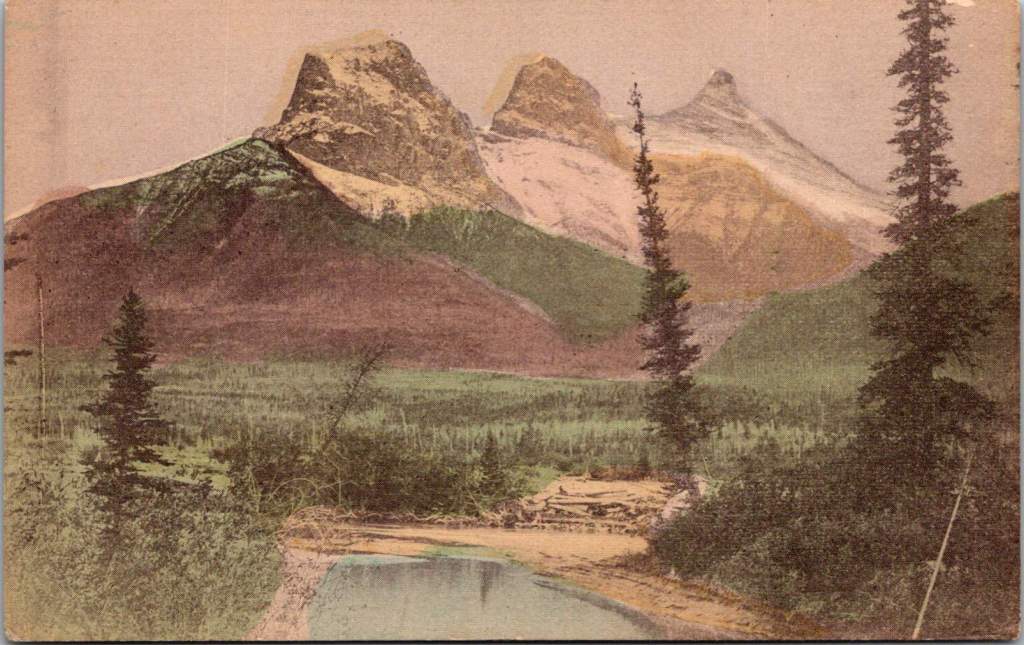

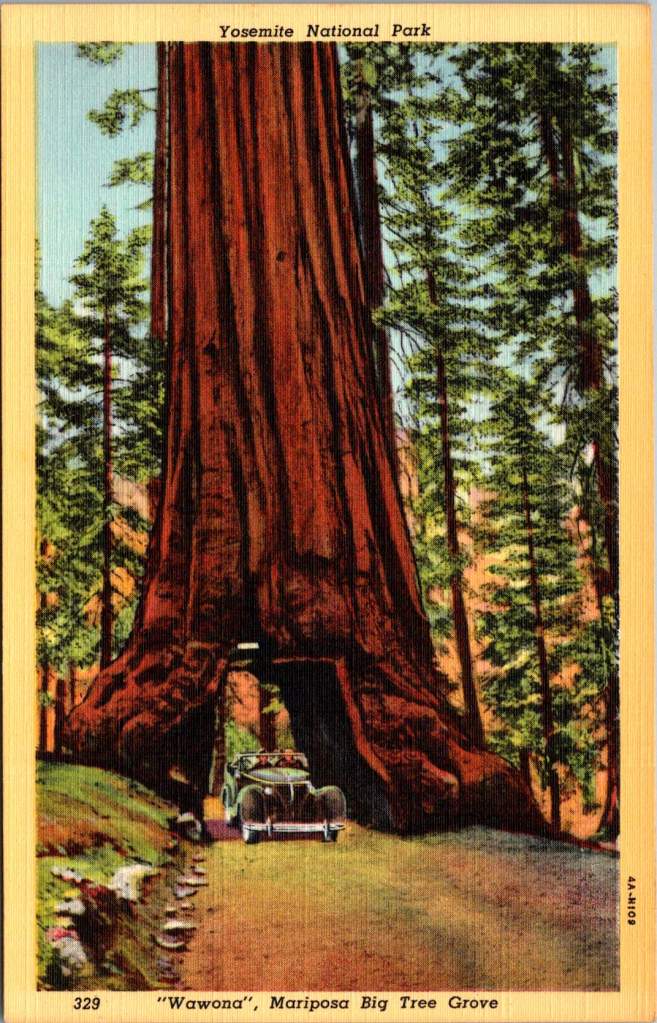

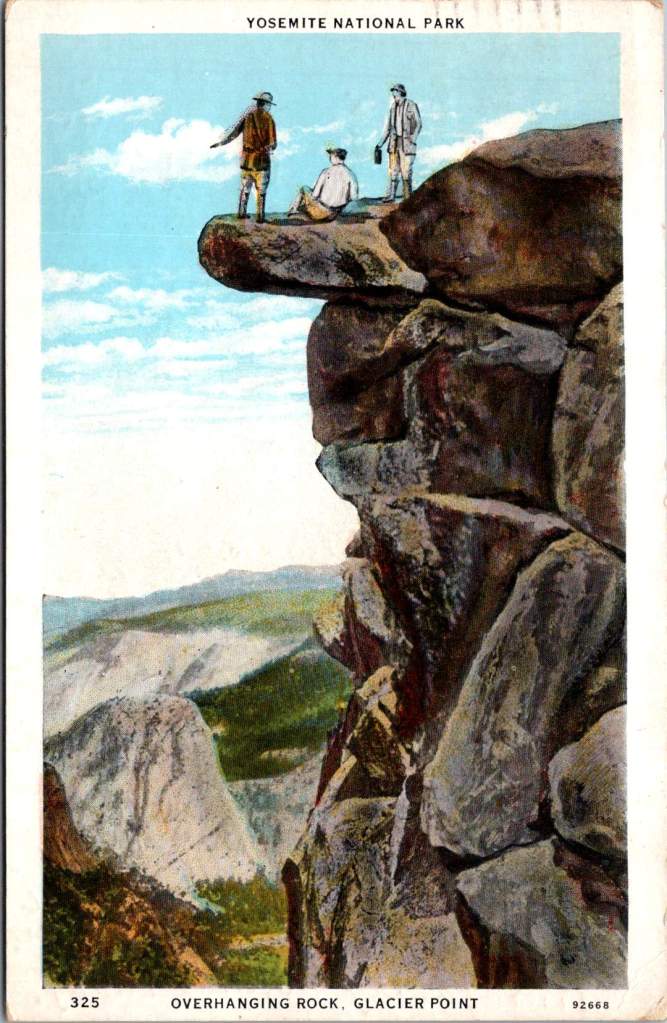

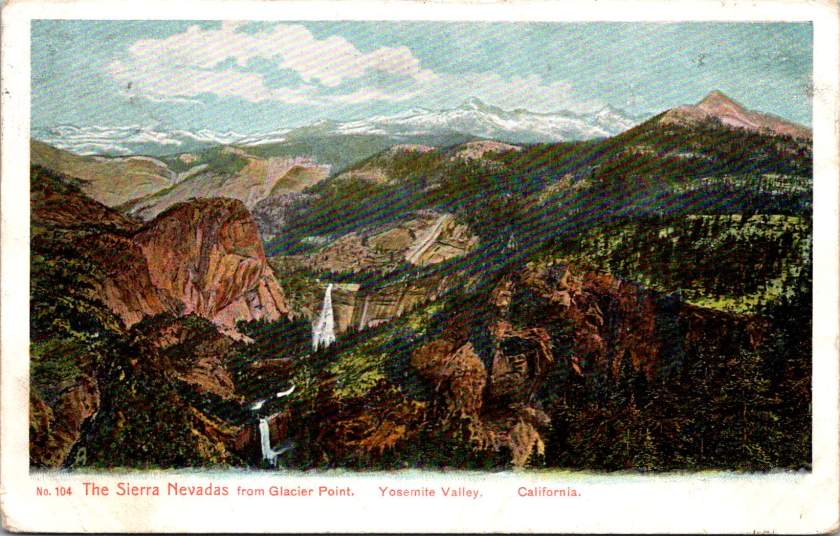

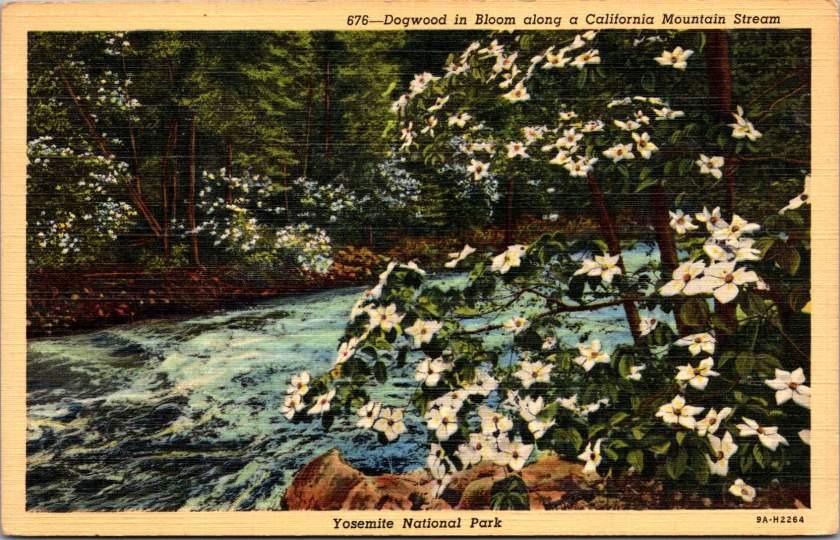

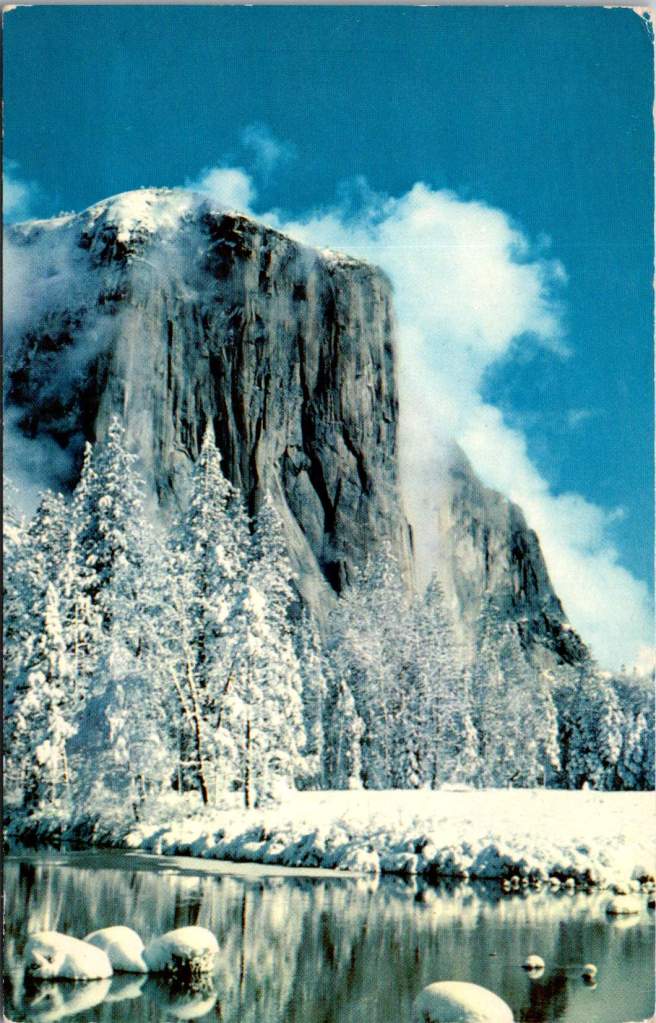

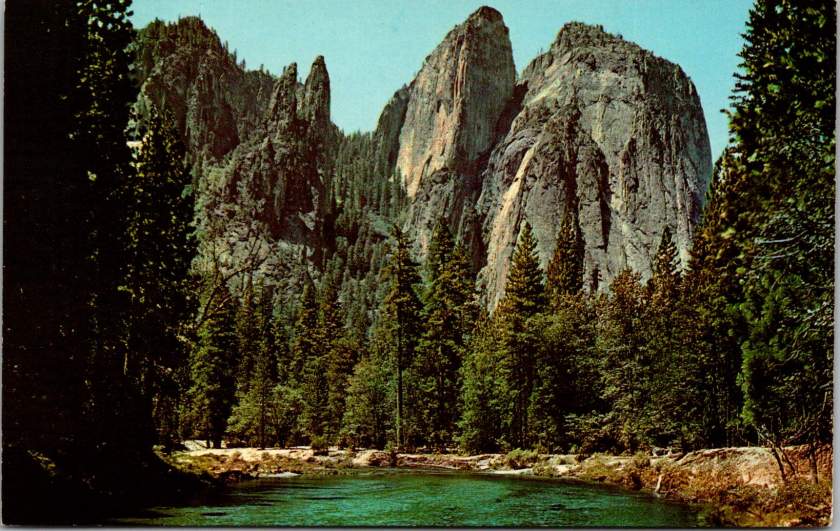

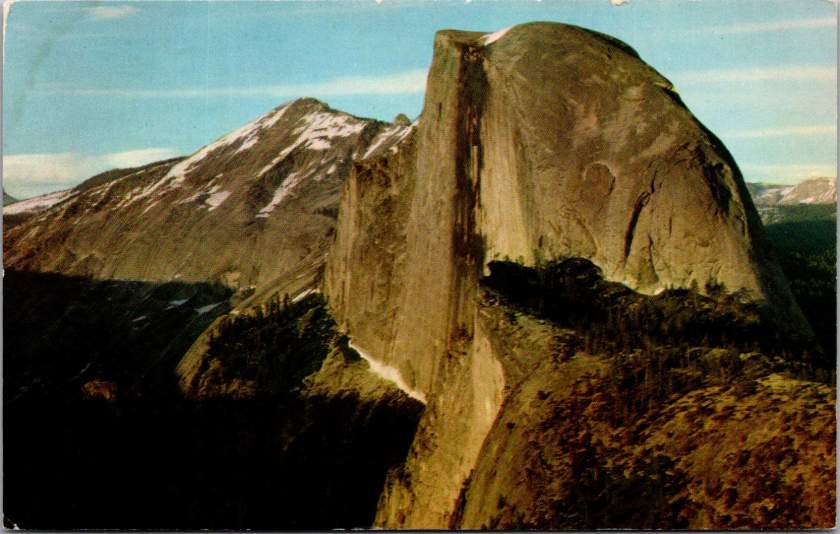

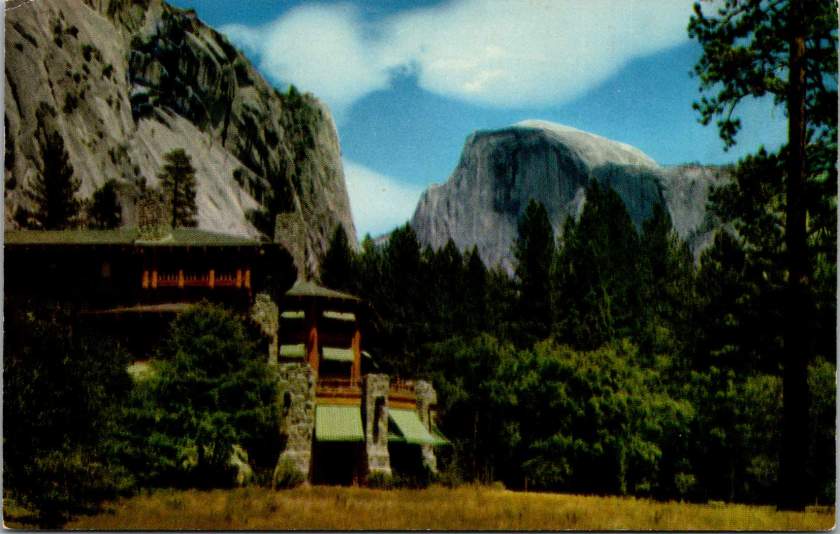

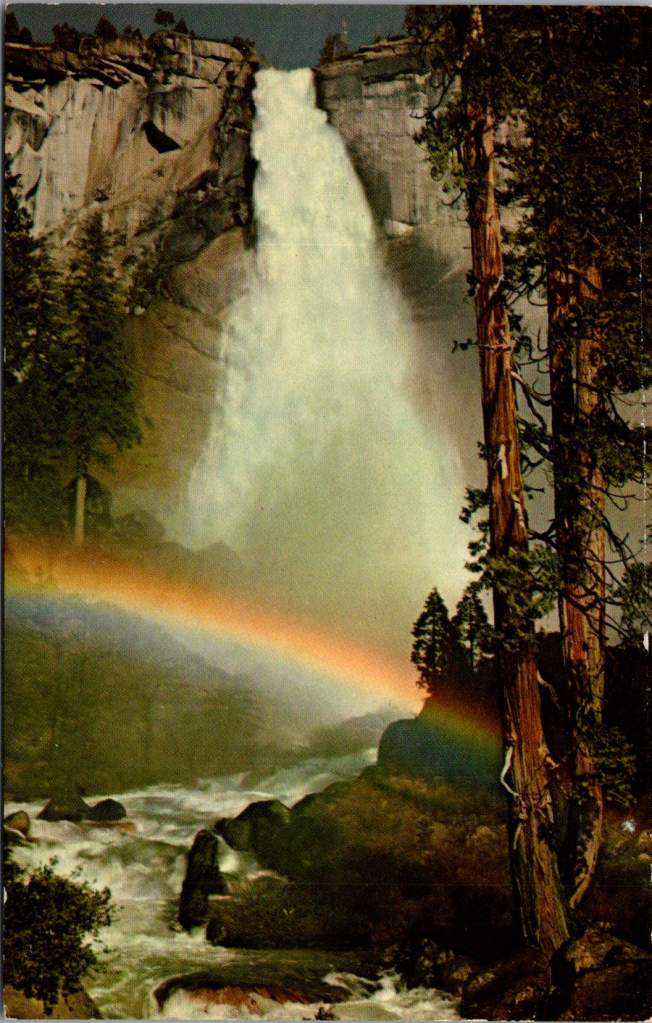

The front of the postcards render multiple iconic American locations in distinctive engravings in an economical two-color print run, an important factor for a the government printing office.

The collection showcases a deliberate balance. Yosemite represents natural power and America’s first national park. Missisippi Riverboats and the Rodeo embody western majesty central to national imagination. DC Monuments offer overt patriotism and Williamsburg and the Liberty Bell connect to the tremors and tolls of colonial democracy.

Even in 1972, these were selective narratives. All featured natural sites exist on traditional Indigenous lands, for example, while largely omitting Indigenous perspectives and enslaved people’s contributions to our cultural histories.

Many featured locations are sacred sites to Indigenous communities. Some of the most sacred places for American Indian nations are located in national parks, yet access to holy ground remains contentious. Park creation often involved displacing Native peoples from lands they had stewarded for millennia.

The year 1972 was tough in other ways: Vietnam War divisions, emerging Watergate scandal, and generational alienation over the military draft. These postcards presented a different kind of unity. Rather than contemporary political divisions, they emphasized natural wonders and historical sites that transcended partisan conflicts.

During the Cold War, these postcards served as miniature global ambassadors, too, often providing people’s first visual encounter with American landmarks. They projected America as worthy of visiting and learning about, countering negative impressions from political controversies.

The postcards themselves embody crucial democratic principles: making heritage accessible through affordable media; connecting tourism to conservation through revenue and public appreciation; and revealing how commemorative choices reflect national values. The geographic diversity suggests a desire for the fullest of American experiences, though these 1972 selections still privilege certain narratives.

New Memories

These postcards continue to offer insights into American values and heritage preservation evolution. USS Constellation still serves as a museum ship in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. National parks have experienced tremendous visitation growth, raising questions about balancing access with preservation.

In what they don’t depict, the postcards show gaps in whose stories get told, whose lands get celebrated, whose experiences get centered. While 1972 selections emphasized traditional narratives, contemporary views increasingly include previously marginalized perspectives, acknowledging Indigenous heritage alongside colonial and national stories.

These artifacts remind us that commemorations reveal values and priorities. As our historical understandings evolve, it’s wise to look back and look again.

To Read More

- Smithsonian National Postal Museum – https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/about-us-stamps-modern-period-1940-present-commemorative-issues/1970-1979

- Historic Ships in Baltimore – USS Constellation documentation

- National Parks Conservation Association – https://www.npca.org/case-studies/national-parks-are-native-lands

- U.S. Department of the Interior – https://www.doi.gov/ocl/tribal-co-management-federal-lands

- National Park Service – https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/trail-of-broken-treaties.htm

- Niagara Falls National Heritage Area – http://www.discoverniagara.org/heritage/history-of-tourism/