The story of Halloween postcards mirrors the evolution of both holiday celebrations and the printing industry through the 20th century. Through these distinctive cards, we can trace changing artistic styles, printing technologies, and cultural attitudes toward this magical and mysterious holiday.

This century-old collection opens a window into an era when German printers, American artists, and local publishers like Salem Paper Company competed to create the perfect Halloween greeting. From dramatic witch flights to cheerful pumpkin-peeking children, these cards tell the story of a holiday—and an industry—in transformation.

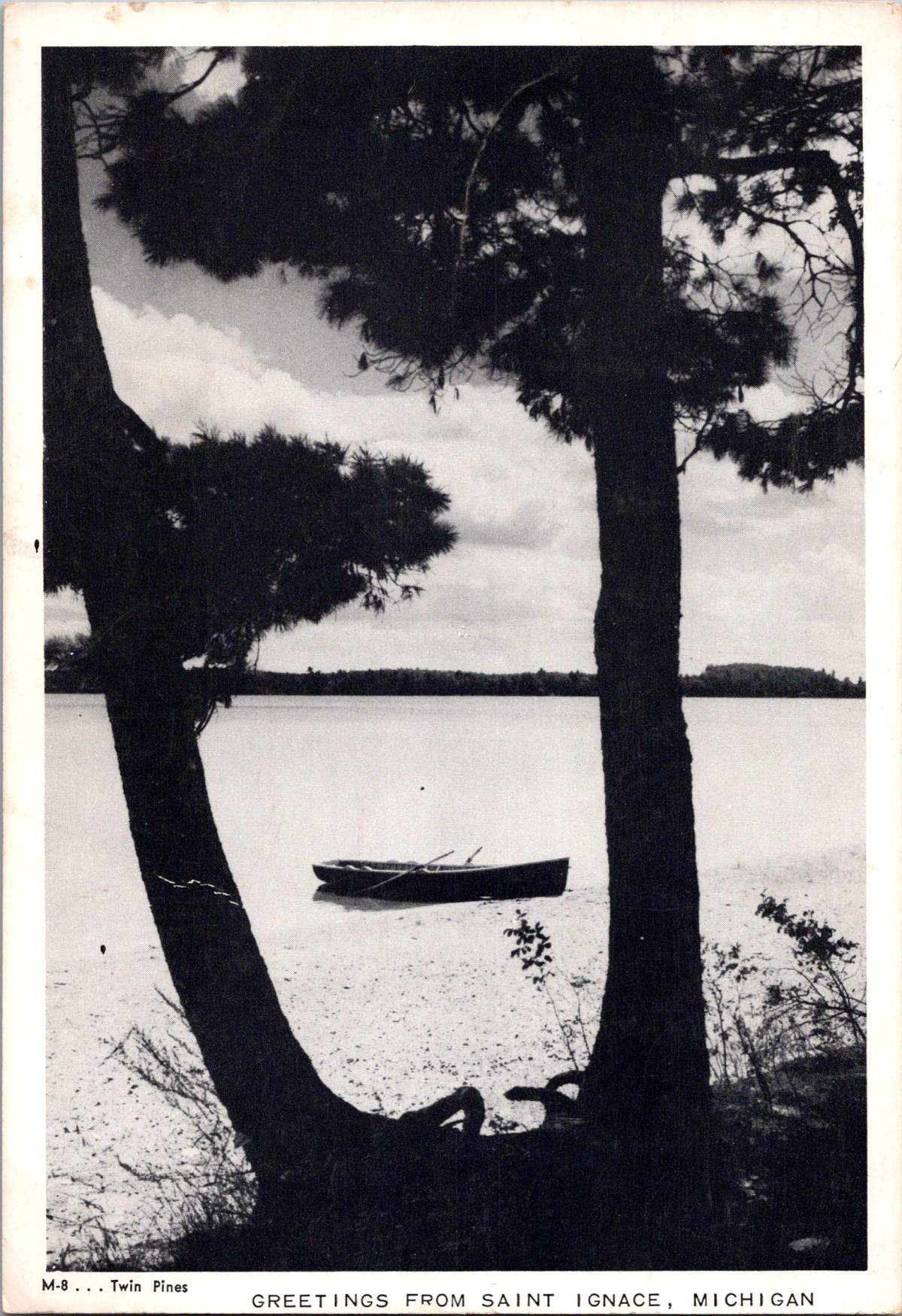

A Starry Halloween in the Golden Age of Postcards

The John Winsch-published “A Starry Halloween” (1913) represents a pinnacle of German chromolithography and American holiday marketing. The card’s verse playfully describes “black Bat aeroplanes.”

“Hallowe’en’s a starry night, You’ll see the Goblins in flight, Perched on their black Bat aeroplanes, They flit about the weather vanes!”

This aeronautical reference demonstrates how postcards of the era incorporated modern technology into traditional Halloween imagery. This whimsical text combines traditional Halloween motifs with early aviation enthusiasm, placing the card squarely in the 1910s zeitgeist.

The card’s detailed execution showcases why German printers dominated the global market before World War I. The deep blue starry sky creates a dramatic backdrop, while the precise color registration and subtle shading of the figures demonstrate the technical excellence of German printing houses.

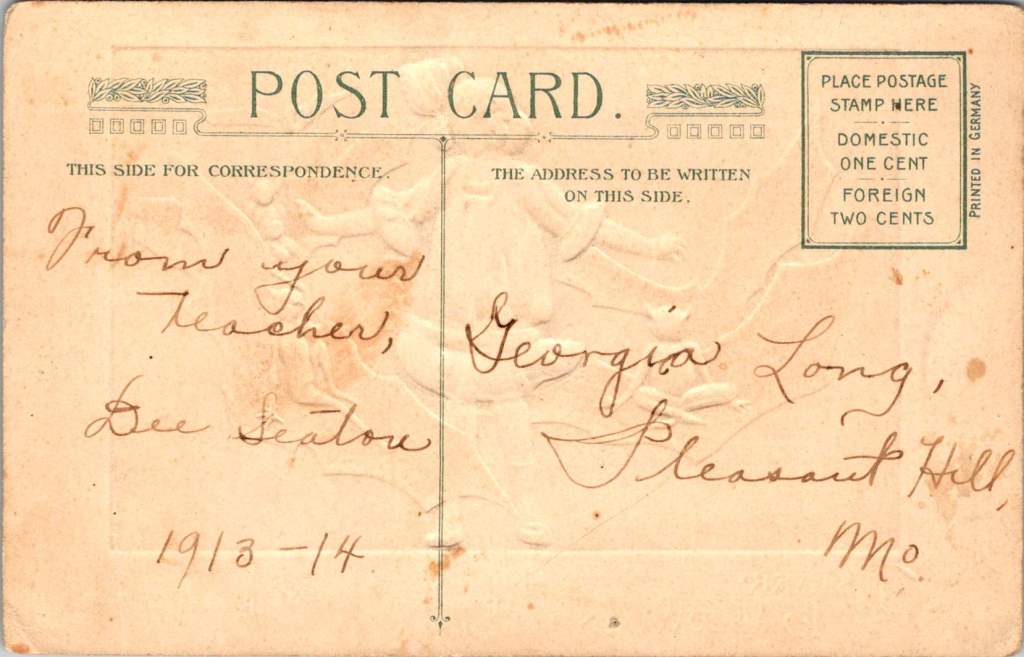

The postcard’s personal inscription—”From your Teacher, Dee Seaton, 1913-14″ to “Georgia Long, Pleasant Hill, Mo.”—reveals how these cards served as important social connections, particularly between teachers and students. The one-cent domestic postage rate, clearly marked on the divided back, reminds us of the affordability of this medium for everyday communication.

Frances Brundage’s Gentle Halloween

The Frances Brundage Halloween cards present a markedly different approach to the holiday in the same era. Known for her sweet-faced children and gentle compositions, Brundage brings her characteristic style to what could be frightening subject matter. The large orange pumpkin dominates the compositions, while a cheerful child with curly hair and a red bow plays with a black cat. The clean white background and red border create a bright, appealing presentation that contrasts with darker Halloween imagery.

Brundage (1854-1937) was among America’s most successful illustrators of children, and her distinctive style—rosy-cheeked, innocent-looking children with expressive faces—is immediately recognizable. Her work appeared on postcards, in children’s books, and in advertising, published by major companies including Raphael Tuck & Sons and Samuel Gabriel & Sons. This Halloween greeting card demonstrates how her gentle artistic approach could make potentially scary holiday themes appropriate for even the youngest children.

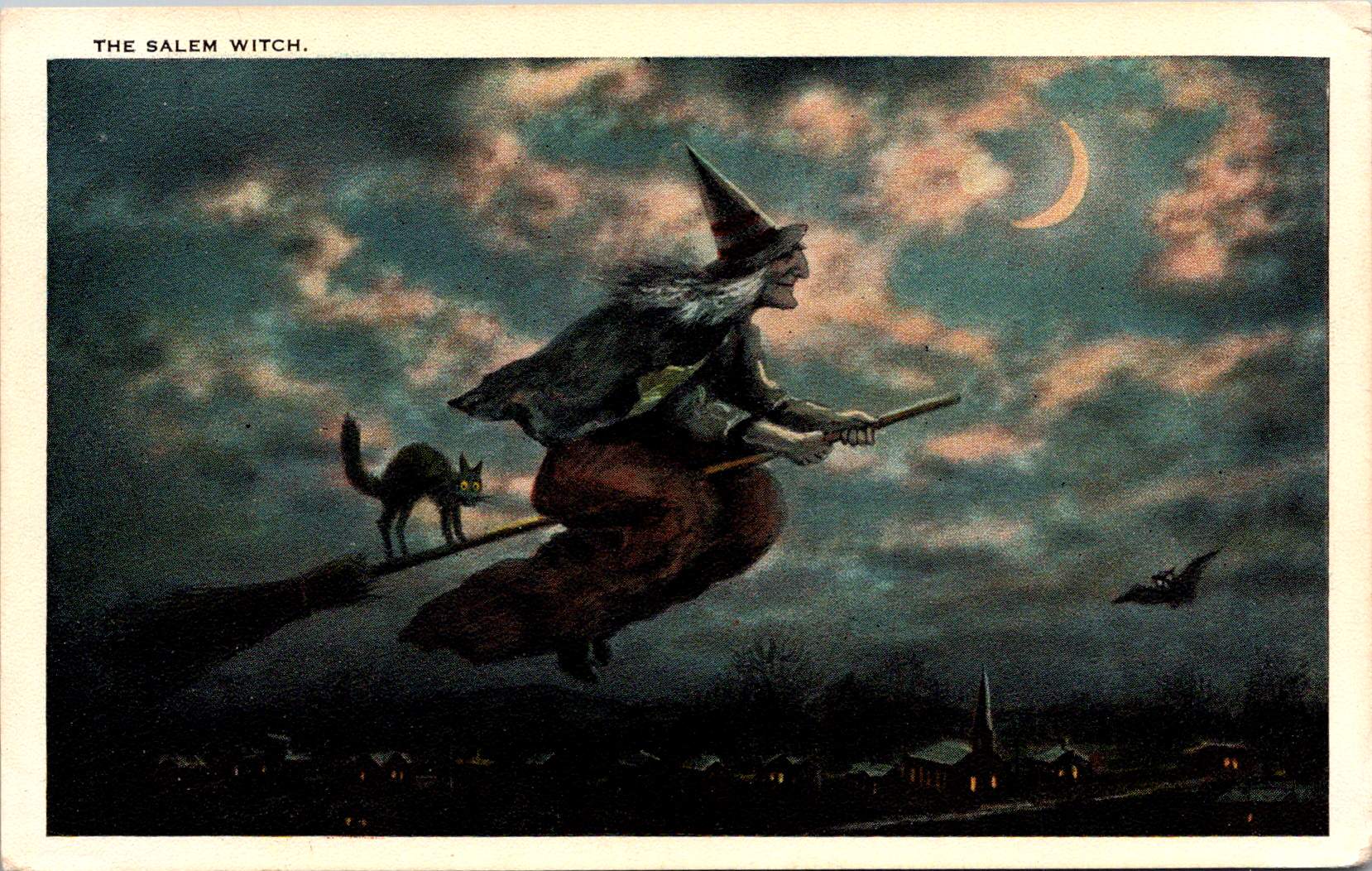

The Salem Witch: Local History Meets Holiday Trade

“The Salem Witch” postcard, published by the Salem Paper Company of Massachusetts, represents a fascinating intersection of local history, holiday celebration, and tourist commerce. The dramatic nighttime scene features a witch in traditional pointed hat and flowing cape, riding a broomstick across a turquoise sky filled with pink-tinged clouds and a crescent moon. A black cat balances behind her on the broomstick, while a bat flies nearby. Below, a small village with lit windows and a church spire creates a sense of scale and setting.

The publisher’s choice to produce this card in Salem was no accident. The city’s notorious witch trials of 1692-93 had by the early 20th century become a tourist draw, and the Salem Paper Company cleverly capitalized on this connection. The card’s dark, moody color palette of deep blues, blacks, and browns creates an appropriately spooky atmosphere.

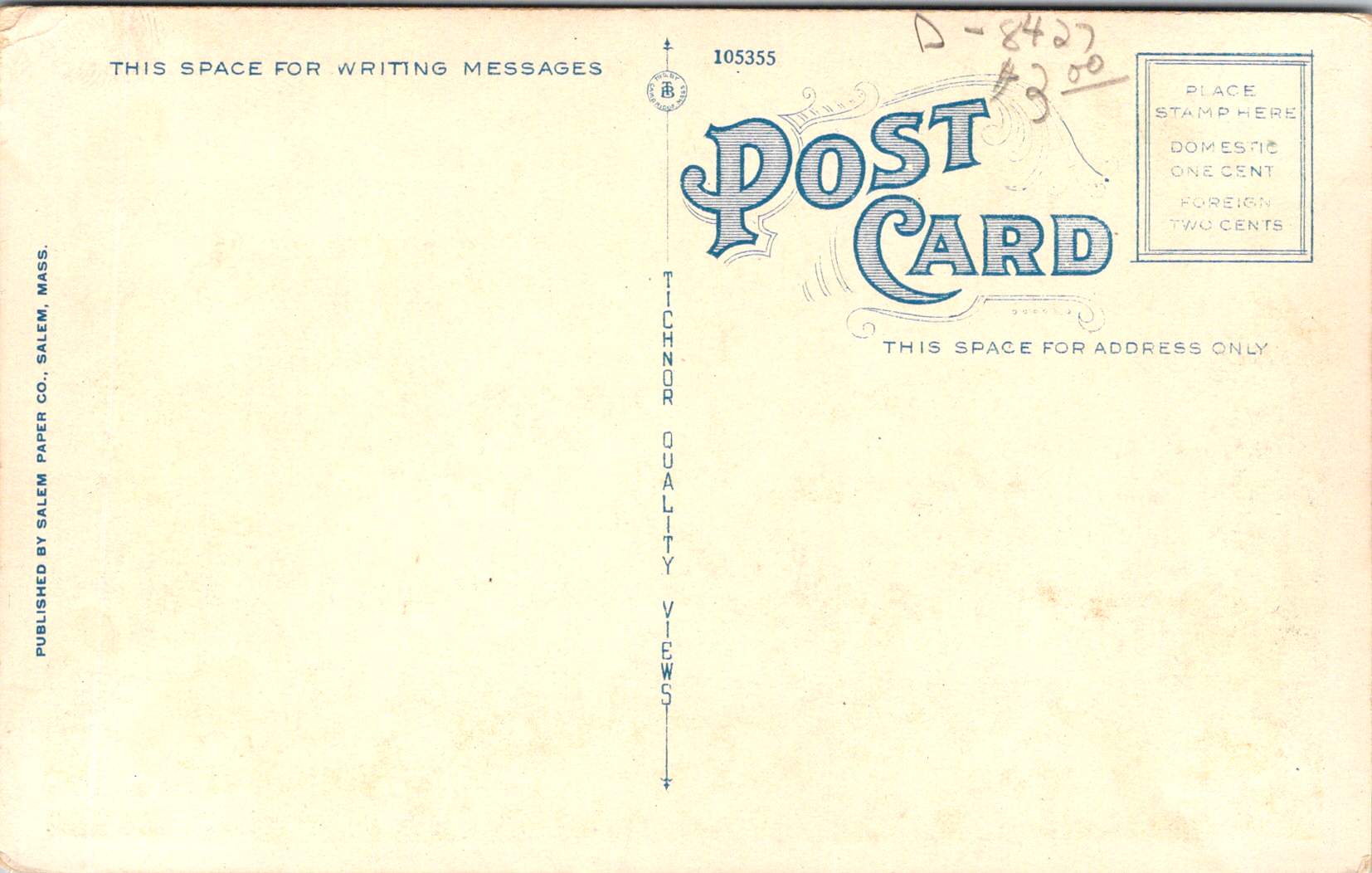

The card’s reverse reveals additional historical details through its markings: PUBLISHED BY SALEM PAPER CO., SALEM, MASS., card number 105355, and the TICHNOR QUALITY VIEWS designation. Tichnor Brothers of Boston was renowned for high-quality postcards, particularly New England scenes, making them an ideal partner for Salem Paper Company’s locally themed Halloween products. The technical quality suggests it was likely also printed in Germany, as were many premium postcards of the era, even those designs that were distinctly American and regional.

The Spooked Kid: From Original to Reproduction

The final card, showing a startled child in white nightclothes against an orange-lit room, represents a later reproduction of Halloween imagery. Produced for Lillian Vernon and printed in Hong Kong, this card likely dates from the 1970s-1990s. But, it draws heavily on early 20th-century artistic conventions. The scene’s elements—a black cat in a window pane, yellow crescent moon, candlestick holder with lit candle, and fallen GHOST STORIES book—all reference classic Halloween postcard motifs. This card’s production history tells the story of significant changes in the postcard industry.

When Lillian Vernon, born in Leipzig, Germany, used her $2,000 wedding gift to launch a mail-order handbag business from her kitchen table in Mount Vernon, New York, in 1951, she could hardly have imagined she would revolutionize American gift retail. That first offering—a matching monogrammed handbag and belt set for $6.98—established the winning formula that would define her business: personalized items at affordable prices. The company name itself, taken from her new hometown, would become synonymous with accessible luxury and thoughtful gifting for generations of American shoppers.

Through the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s, Lillian Vernon catalogs were a fixture in American mailboxes, eagerly anticipated by parents and children alike. The company mastered the art of “catch-penny” items—small, impulse-buy treasures that seemed irresistible at their price points. Their most beloved offerings included personalized school supplies (from pencil cases to lunch boxes), holiday decorations, monogrammed doormats, and children’s toys. The company’s success made history in 1987 when Lillian Vernon became the first woman-owned company to be listed on the American Stock Exchange, a milestone in American business history.

By the time the company began sourcing products like Halloween postcards from Hong Kong printers, Lillian Vernon had transformed from a small mail-order business into a retail empire that included multiple specialized catalogs, retail stores, and eventually an online presence. The company’s choice to have the card printed in Hong Kong reflects the late 20th-century shift of printing operations from Europe and America to Asia, prioritizing cost-effective production over the artistic merit and technical excellence that characterized the German chromolithography era.

Though the company would ultimately close in 2016, unable to fully adapt to the digital age, its influence on American retail culture remains significant. The Lillian Vernon story represents both the American dream and the evolution of modern commerce—from kitchen-table startup to national brand, from personalized service to mass-market appeal, from mail-order catalogs to the small business opportunities of the internet era.

The Evolution of an Industry

These postcards trace the evolution of Halloween greetings from the golden age of German printing through the modern reproduction era. The Winsch card represents the height of pre-WWI German chromolithography and original holiday artwork. Frances Brundage’s contribution shows how established American artists adapted holiday themes for children. The Salem Witch card demonstrates the growing commercialization of local history and holiday traditions. Finally, the Lillian Vernon reproduction reveals how these vintage designs found new life in the mass-market retail era.

Together, they tell a story not just of changing printing technologies and business models, but of the evolving relationship with Halloween itself. From the elaborate artistic productions of the 1910s through the mass-market reproductions of the late 20th century, Halloween postcards have both reflected and shaped how Americans celebrate this fascinating holiday.

The Halloween postcard industry’s journey from German printing houses through American publishers to Asian manufacturers parallels larger trends in American commerce and holiday celebrations. These cards remain valuable historical documents, preserving not just artistic styles and printing techniques, but also the personal connections and social customs of their eras. Whether sent by a teacher to a student in 1913 or purchased as a souvenir in more recent decades, each card represents a tangible link to the holiday and shared heritage.