New Discoveries from a Lost Archive

Last week’s essay examined the American occupation of Coblenz, a unique period of military history, through the photographic lens of Lindstedt & Zimmermann. The Lindstedt & Zimmermann studio was destroyed during Allied bombing in World War II, decimating their archive and rendering the surviving examples of their work as uncommon historical artifacts.

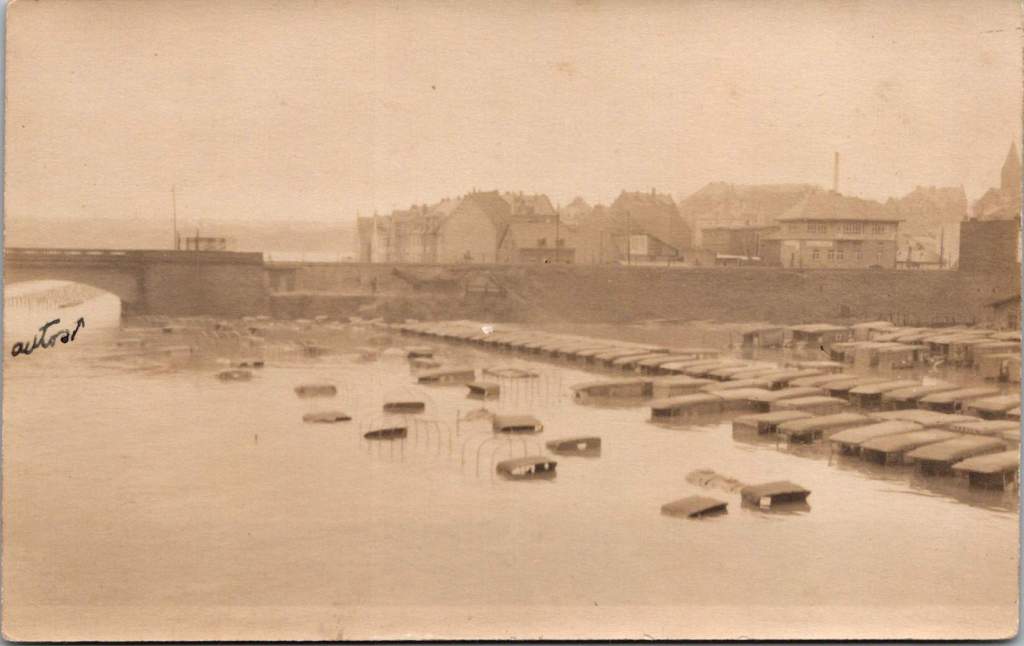

The exchange with the research team prompted another search through our postcard collection resulting in the discovery of 25 additional images. Most can be attributed to Lindstedt & Zimmermann based on stylistic elements, materials and subject matter. Some bear the mark of other photographers including Paul Stein, another Coblenz studio. Ten photographs document the catastrophic flood of the Rhine in January 1920 – images that likely haven’t been seen in a century.

The Great Flood of January 1920

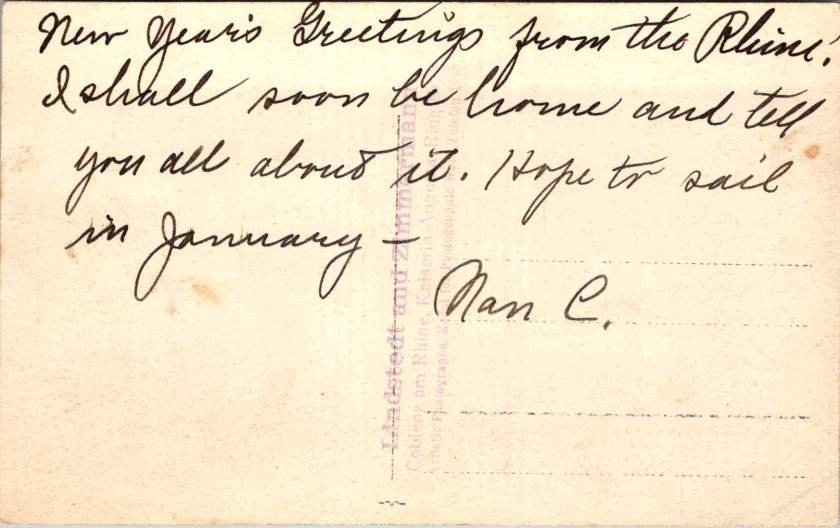

The January 1920 flood represented one of the most significant natural disasters to impact the American occupation forces during their tenure in Germany. The handwritten note on one postcard reveals both the severity of the flood and its impact on the American presence. This mixed German-English description captures the cross-cultural nature of the occupation.

“Der Rhein hat über its banks geflowed und Uncle Sam’s autos gdamaged. The river is the highest in over a hundred years, almost beyond my memory!”

The photographs show numerous small boats navigating the water and automobiles partially submerged in floodwaters, with bridges and buildings visible in the background. These images provide rare documentation of a significant environmental event that temporarily disrupted occupation activities and required adaptation by both American forces and local residents.

Harlem Hellfighters

This very rare view shows what appears to be members of an African American regimental band with their instruments at Romagne, France. Black men served in segregated units during World War I, with regiments such as the 369th Infantry (the “Harlem Hellfighters”) earning recognition for their service. Their regimental bands played an important cultural role, introducing European audiences to American jazz and ragtime music. These musical ambassadors created cultural connections that transcended the military context of their presence. The inclusion of this photograph adds an important dimension to our understanding of the American military presence in post-war Europe, highlighting the contributions of African American servicemen whose stories have been marginalized in historical accounts.

YMCA Women

The expanded collection also includes two formal portraits of women in YMCA uniform, complete with the organization’s distinctive triangular insignia on hat and lapel. Sometimes called Y girls, female YMCA workers provided essential services for American soldiers stationed far from home. They operated canteens, organized recreational activities, offered educational programs, and provided a connection to American civilian life that helped maintain morale during the occupation period.

The YMCA was among the few organizations that deployed American women to work directly with troops overseas during this era. These women volunteers typically came from educated, middle or upper-class backgrounds and represented an early example of American women engaging in international service work. Their presence added a civilian dimension to the occupation and helped create environments where American soldiers could productively spend their off-duty hours.

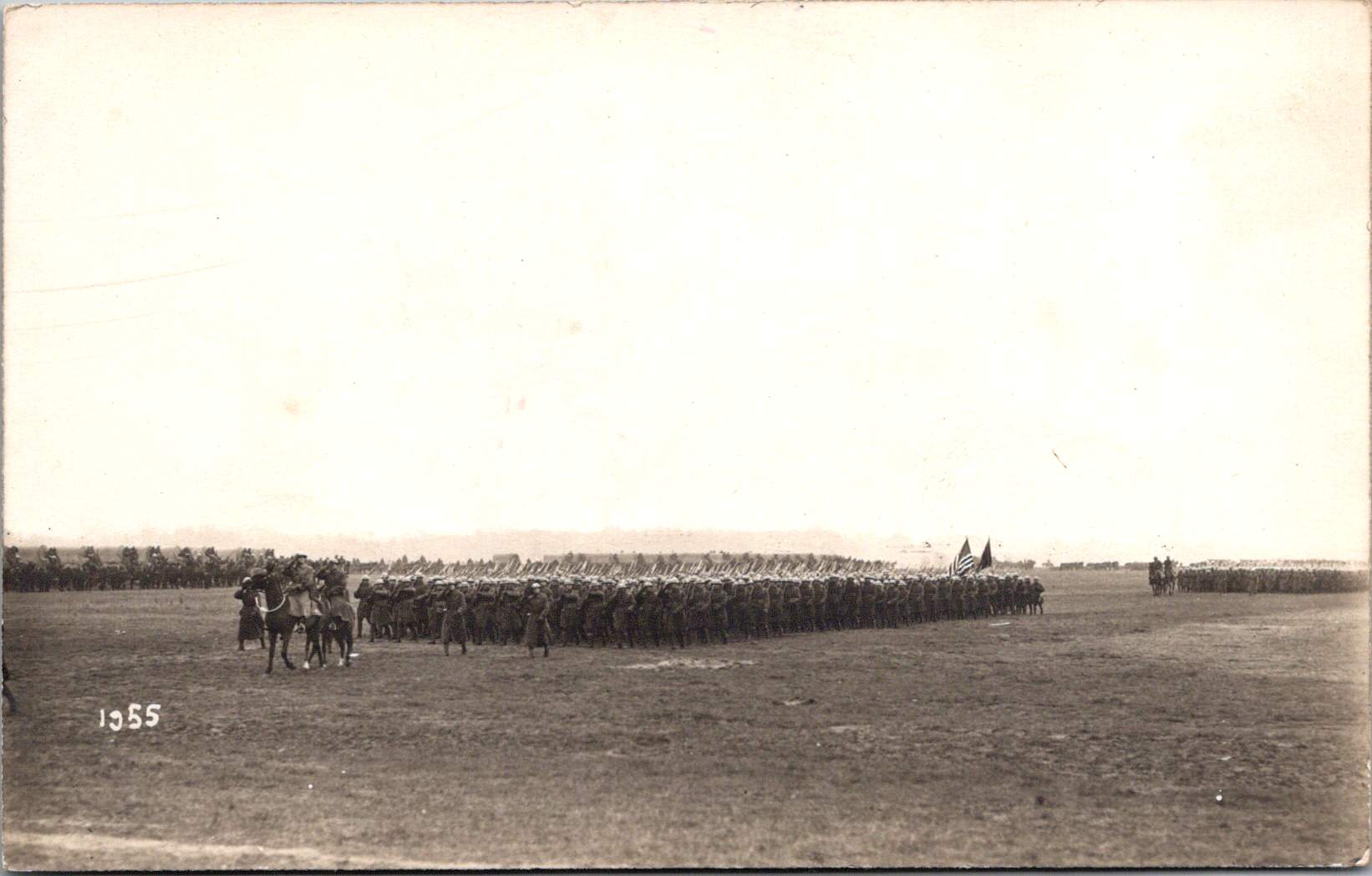

Military Pageantry and Daily Operations

One striking photograph shows the 76th Field Artillery Regiment arranged in a “living insignia” formation, with soldiers positioned to create the unit’s distinctive diagonal striped insignia, surrounded by artillery pieces. This type of military display was meant to demonstrate American capacity while building unit cohesion and pride, and perhaps avert a little boredom.

In contrast to these ceremonial arrangements, other photographs document the practical transportation and logistical elements that supported daily operations. An image of a young driver with his heavy-duty truck along what appears to be the Rhine riverbank represents the essential supply operations that maintained the American presence. The vehicle’s utilitarian design with solid rubber tires, wooden spoke wheels, and large cargo bed illustrates the practical equipment used to transport supplies, equipment, and personnel throughout the occupation zone.

French Military Presence

The next image shows a group portrait of four French soldiers in their distinctive uniforms. Easily identified by their characteristic “Adrian” helmets with the prominent crest ridge along the top and the horizon blue (bleu horizon) uniform that became emblematic of French forces during World War I, these men represent the broader Allied presence in post-war Germany.

France maintained the largest occupation zone in the Rhineland, reflecting their particular security concerns regarding Germany. French forces occupied territories including Mainz, while American forces centered on Coblenz and British forces on Cologne. Later, French forces took over the Coblenz occupation.

The portrait format was typical of military mementos during this era, allowing soldiers to document their service and send images to family members. The survival of any images at all is due to this distribution by soldiers to their home countries.

Beyond Coblenz

Not all images in the collection were taken in Coblenz itself. One photograph shows American personnel in a touring car filled with passengers in what may be the French Riviera, identifiable by its distinctive palm trees and Mediterranean architecture. Dating to 1921-1923 based on the automobile’s style, this photograph represents the recreational opportunities available to some American personnel during leave periods from their occupation duties.

Europe allowed for cultural and recreational experiences that would have been impossible for most Americans of this era. For many young Americans serving in the occupation forces, this European assignment represented their first—and perhaps only—opportunity to experience the wider world beyond their home communities.

Visual Legacies

The survival of these photographs, particularly those documenting the 1920 flood, represents a remarkable preservation of visual history that might otherwise have been lost entirely. With the bombing of the Lindstedt & Zimmermann studio during World War II, the unique nature of real photo postcards, and the general fragility of materials from this era, each surviving image offers a rare window into this formative period in world relations.

Karl and Änne Zimmermann’s work, along with that of contemporaries like Paul Stein, provides an invaluable visual chronicle of the first American occupation of European territory—a precedent for the much larger American military presence that would emerge in Europe after World War II. Their photographs capture not just military operations and formal events but the daily reality of cross-cultural interaction between Americans, French, and Germans during this unique historical moment and place.