I wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year with just lots of love to each & every one. Lovingly, Auntie Mary

Each year, simple messages usher us into the new and next. Like Auntie Mary a century ago, I’m sending lots of love to each & every one.

I wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year with just lots of love to each & every one. Lovingly, Auntie Mary

With just nine words, this 1964 parody postcard captures an era of bureaucratic absurdity. The genius lies in its perfect circularity: you can’t disregard a notice you never received. A logical paradox delivered in the stern capital letters of official communication.

This masterpiece of meta-humor was the centerpiece of “Nutty Notices,” a collection of satirical postcards published by Philadelphia’s GEM Publishing in 1964. The series went on to skewer everything from traffic enforcement to mattress tags, each card delivering bureaucratic absurdity like a stage clown wielding a rubber chicken.

Perfect for the spooky season, the next notice solemnly announces the recipient has won in an “Imminent Danger Sweepstakes” sponsored by a “Black Cat Society,” reassuring that previous recipients survived their subsequent accidents.

The collection unfolds like a greatest hits of paperwork problems. Another, from the stern-sounding “Bureau of Upholstery Tag Security,” threatens dawn raids over a removed mattress tag. A mock inheritance notice dangles a too-good-to-be-true fortune from a conveniently deceased fifth cousin, key details lost to a faulty typewriter.

These parodies emerged during a period of notable government expansion. The Great Society legislation of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations had launched numerous new agencies and programs, from the Peace Corps to Medicare. While many of these programs were popular, and have endured, they also generated unprecedented levels of paperwork and official communications in Americans’ daily lives.

The notices cleverly played on specific anxieties of the era: fear of government surveillance, concerns about traffic enforcement in the new Interstate era, and awareness of inheritance scams in an increasingly connected society.

The traffic violation notice, featuring President Lyndon B. Johnson, plays on LBJ’s notorious driving habits. The President was known for terrifying guests at his Texas ranch by driving his Amphicar (a German-made civilian amphibious vehicle) at high speeds toward the ranch’s lake, screaming about brake failure as his car plunged into the water. The vehicle was designed to float, but his unsuspecting passengers didn’t know that. This well-known presidential prank made the postcard’s joke particularly resonant with 1960s readers.

A good pun is still a kind of social capital, as all deadpanning dads know. The card below suggests an incredible win. The 1964 Plymouth Barracuda was a coveted car model, though overshadowed that year by the introduction of the Ford Mustang. The Barracuda featured a sloped fastback roofline and fold-down rear seats that created a large cargo area, making it both sporty and practical. The standard engine was a Slant-6, but buyers could opt for a more powerful V8 engine. Prices started at around $2,500 (approximately $22,000 in today’s dollars). By the end of the card, though, it’s all a bit fishy.

What makes these 1964 parodies fundamentally different from today’s deceptive communications is their clear satirical intent. The notices were obviously humorous, from their outlandish premises to their absurd escalations. They never attempted to deceive. The parodies didn’t seek to extract money, personal information, or action from recipients. The joke was the endpoint, and publishers and recipients understood these as entertainment, part of a broader tradition of bureaucratic satire.

Today’s deceptive communications often weaponize the same official-looking formats and bureaucratic language that these postcards once parodied. But modern scams aim to deceive rather than amuse, exploiting digital tools to create ever more convincing forgeries. Contemporary examples like phishing emails represent a darker evolution of institutional mimicry. While the 1964 notices laughed at authority’s pomposities, today’s deceptive communications abuse institutional authority for malicious purposes.

Long before memes spread political humor online, postcards served as a democratic medium for both serious political discourse and satirical commentary. During the Golden Age of postcards before World War I, suffragettes used them to promote women’s voting rights. The famous “Vinegar Valentines” of the Victorian era delivered stinging social critique through the mail. During World War II, patriotic postcards boosted morale while propaganda postcards spread messages both noble and nefarious.

These vintage parodies remind us that healthy skepticism toward official communications isn’t new—but the stakes have changed dramatically. In 1964, Americans could laugh at mock notices because real ones, while annoying, generally came through trusted channels with clear verification methods. Today’s digital landscape requires a more sophisticated type of visual and contextual literacy. We must balance healthy skepticism with the ability to recognize legitimate communications, while remaining alert to increasingly sophisticated forms of deception.

The “Nutty Notices” stand as charming artifacts of a time when bureaucratic busy-ness seemed worthy of laughter rather than alarm—when the worst thing a notice might do was create a paradox, not steal your identity. In an era of digital manipulation, we can look back nostalgically at a time when the most threatening official communication you might receive was a tongue-in-cheek warning about your mattress tags.

Against a star-strewn midnight sky, a girl in white stands fearless in front of a gleaming full moon while impish red devils perch on bat wings around her. This whimsical scene, printed in Germany in 1913, captures the magic of Halloween’s golden age, when postcards were miniature works of art and All Hallows’ Eve still balanced precariously between spooky and sweet.

The story of Halloween postcards mirrors the evolution of both holiday celebrations and the printing industry through the 20th century. Through these distinctive cards, we can trace changing artistic styles, printing technologies, and cultural attitudes toward this magical and mysterious holiday.

This century-old collection opens a window into an era when German printers, American artists, and local publishers like Salem Paper Company competed to create the perfect Halloween greeting. From dramatic witch flights to cheerful pumpkin-peeking children, these cards tell the story of a holiday—and an industry—in transformation.

The John Winsch-published “A Starry Halloween” (1913) represents a pinnacle of German chromolithography and American holiday marketing. The card’s verse playfully describes “black Bat aeroplanes.”

“Hallowe’en’s a starry night, You’ll see the Goblins in flight, Perched on their black Bat aeroplanes, They flit about the weather vanes!”

This aeronautical reference demonstrates how postcards of the era incorporated modern technology into traditional Halloween imagery. This whimsical text combines traditional Halloween motifs with early aviation enthusiasm, placing the card squarely in the 1910s zeitgeist.

The card’s detailed execution showcases why German printers dominated the global market before World War I. The deep blue starry sky creates a dramatic backdrop, while the precise color registration and subtle shading of the figures demonstrate the technical excellence of German printing houses.

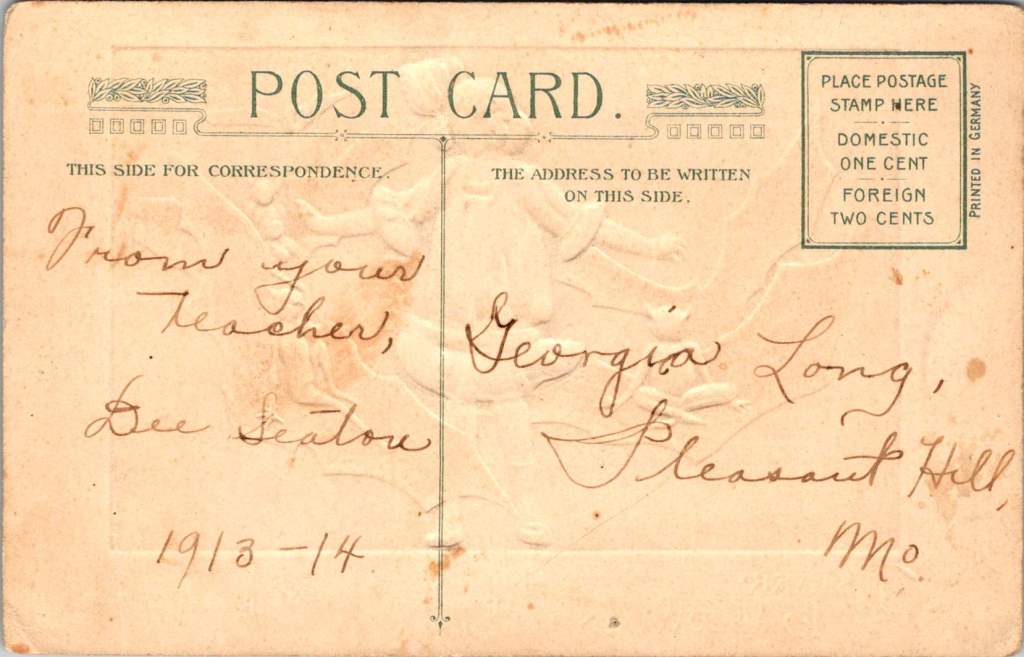

The postcard’s personal inscription—”From your Teacher, Dee Seaton, 1913-14″ to “Georgia Long, Pleasant Hill, Mo.”—reveals how these cards served as important social connections, particularly between teachers and students. The one-cent domestic postage rate, clearly marked on the divided back, reminds us of the affordability of this medium for everyday communication.

The Frances Brundage Halloween cards present a markedly different approach to the holiday in the same era. Known for her sweet-faced children and gentle compositions, Brundage brings her characteristic style to what could be frightening subject matter. The large orange pumpkin dominates the compositions, while a cheerful child with curly hair and a red bow plays with a black cat. The clean white background and red border create a bright, appealing presentation that contrasts with darker Halloween imagery.

Brundage (1854-1937) was among America’s most successful illustrators of children, and her distinctive style—rosy-cheeked, innocent-looking children with expressive faces—is immediately recognizable. Her work appeared on postcards, in children’s books, and in advertising, published by major companies including Raphael Tuck & Sons and Samuel Gabriel & Sons. This Halloween greeting card demonstrates how her gentle artistic approach could make potentially scary holiday themes appropriate for even the youngest children.

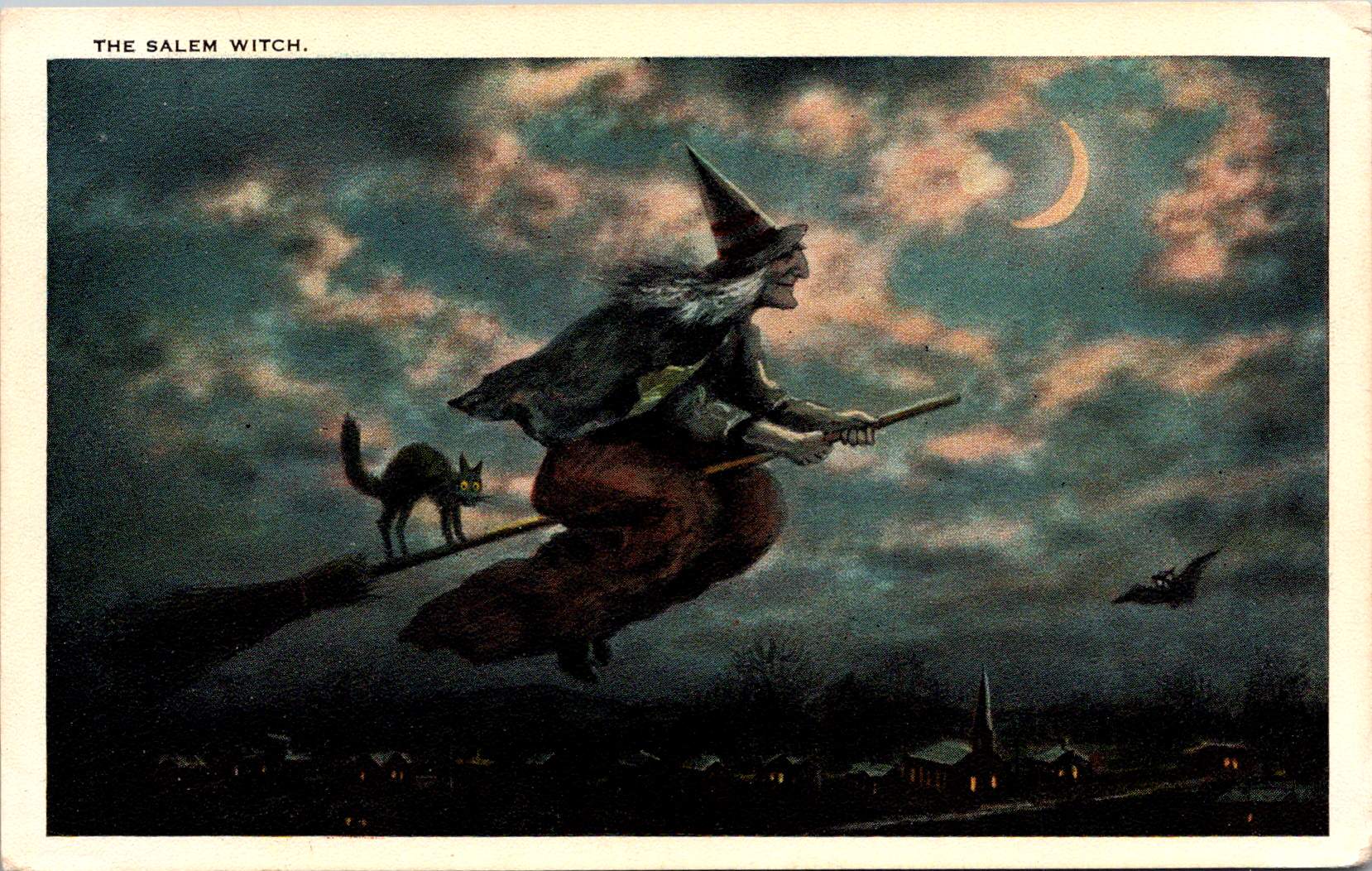

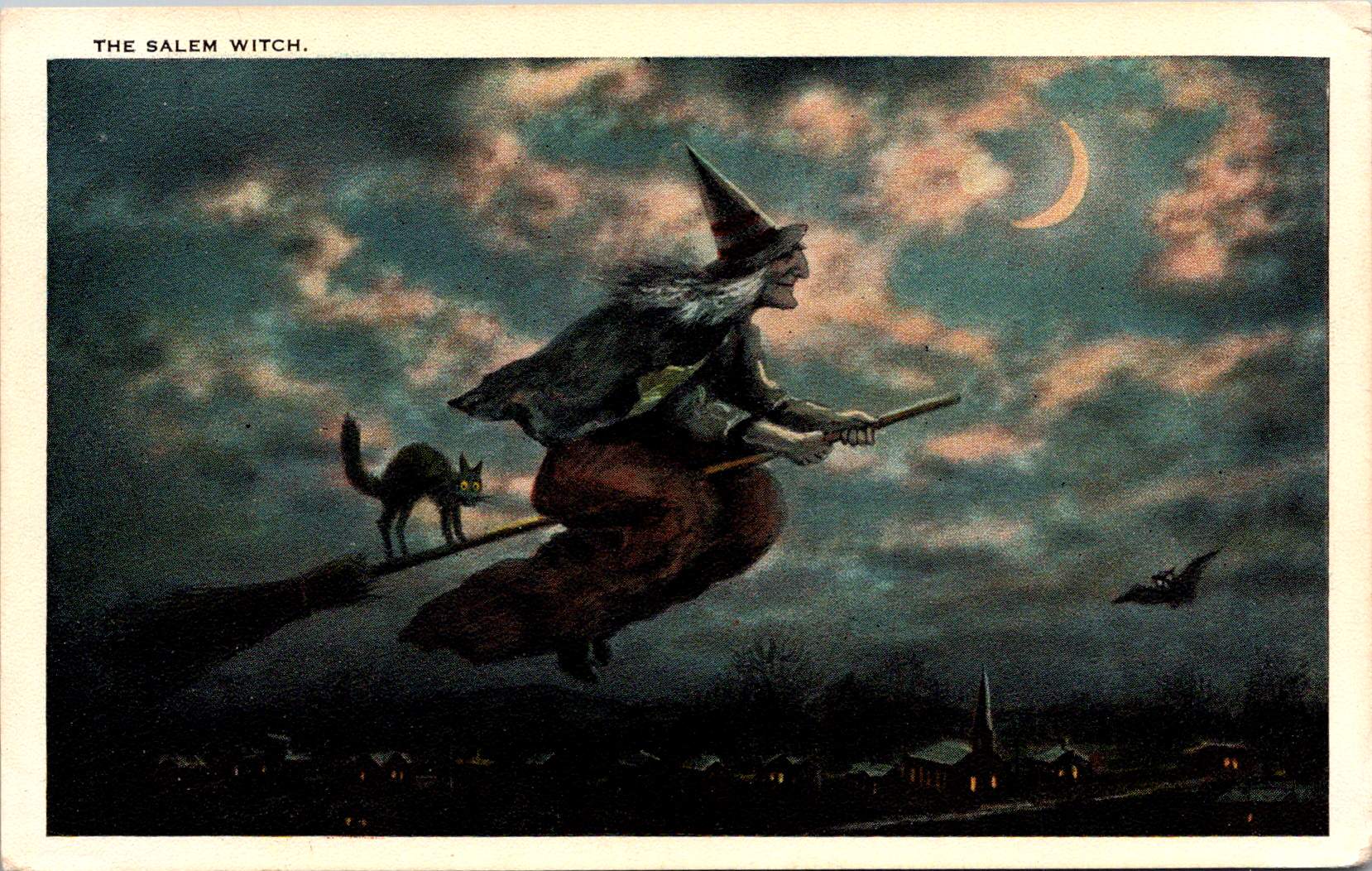

“The Salem Witch” postcard, published by the Salem Paper Company of Massachusetts, represents a fascinating intersection of local history, holiday celebration, and tourist commerce. The dramatic nighttime scene features a witch in traditional pointed hat and flowing cape, riding a broomstick across a turquoise sky filled with pink-tinged clouds and a crescent moon. A black cat balances behind her on the broomstick, while a bat flies nearby. Below, a small village with lit windows and a church spire creates a sense of scale and setting.

The publisher’s choice to produce this card in Salem was no accident. The city’s notorious witch trials of 1692-93 had by the early 20th century become a tourist draw, and the Salem Paper Company cleverly capitalized on this connection. The card’s dark, moody color palette of deep blues, blacks, and browns creates an appropriately spooky atmosphere.

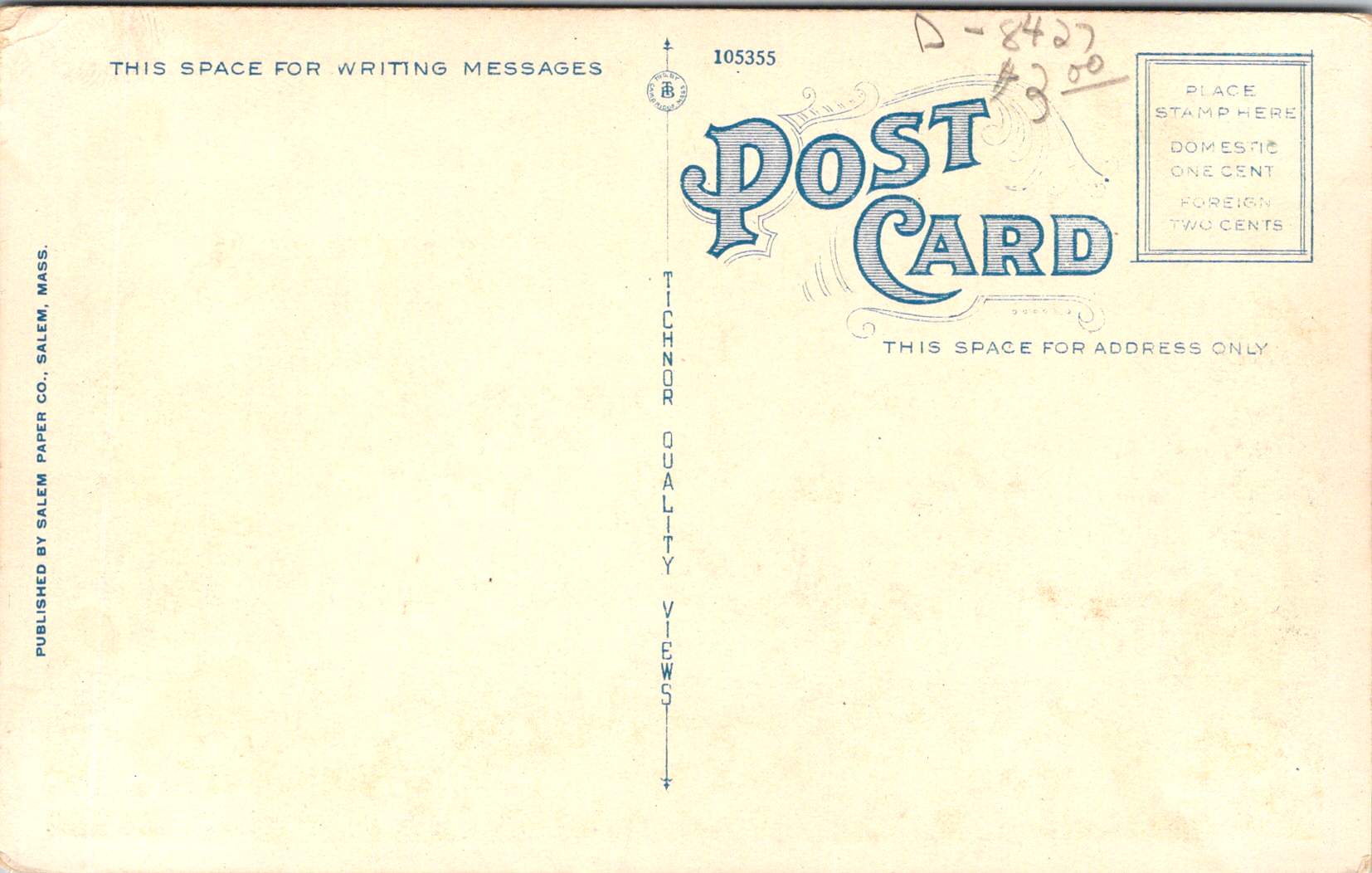

The card’s reverse reveals additional historical details through its markings: PUBLISHED BY SALEM PAPER CO., SALEM, MASS., card number 105355, and the TICHNOR QUALITY VIEWS designation. Tichnor Brothers of Boston was renowned for high-quality postcards, particularly New England scenes, making them an ideal partner for Salem Paper Company’s locally themed Halloween products. The technical quality suggests it was likely also printed in Germany, as were many premium postcards of the era, even those designs that were distinctly American and regional.

The final card, showing a startled child in white nightclothes against an orange-lit room, represents a later reproduction of Halloween imagery. Produced for Lillian Vernon and printed in Hong Kong, this card likely dates from the 1970s-1990s. But, it draws heavily on early 20th-century artistic conventions. The scene’s elements—a black cat in a window pane, yellow crescent moon, candlestick holder with lit candle, and fallen GHOST STORIES book—all reference classic Halloween postcard motifs. This card’s production history tells the story of significant changes in the postcard industry.

When Lillian Vernon, born in Leipzig, Germany, used her $2,000 wedding gift to launch a mail-order handbag business from her kitchen table in Mount Vernon, New York, in 1951, she could hardly have imagined she would revolutionize American gift retail. That first offering—a matching monogrammed handbag and belt set for $6.98—established the winning formula that would define her business: personalized items at affordable prices. The company name itself, taken from her new hometown, would become synonymous with accessible luxury and thoughtful gifting for generations of American shoppers.

Through the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s, Lillian Vernon catalogs were a fixture in American mailboxes, eagerly anticipated by parents and children alike. The company mastered the art of “catch-penny” items—small, impulse-buy treasures that seemed irresistible at their price points. Their most beloved offerings included personalized school supplies (from pencil cases to lunch boxes), holiday decorations, monogrammed doormats, and children’s toys. The company’s success made history in 1987 when Lillian Vernon became the first woman-owned company to be listed on the American Stock Exchange, a milestone in American business history.

By the time the company began sourcing products like Halloween postcards from Hong Kong printers, Lillian Vernon had transformed from a small mail-order business into a retail empire that included multiple specialized catalogs, retail stores, and eventually an online presence. The company’s choice to have the card printed in Hong Kong reflects the late 20th-century shift of printing operations from Europe and America to Asia, prioritizing cost-effective production over the artistic merit and technical excellence that characterized the German chromolithography era.

Though the company would ultimately close in 2016, unable to fully adapt to the digital age, its influence on American retail culture remains significant. The Lillian Vernon story represents both the American dream and the evolution of modern commerce—from kitchen-table startup to national brand, from personalized service to mass-market appeal, from mail-order catalogs to the small business opportunities of the internet era.

These postcards trace the evolution of Halloween greetings from the golden age of German printing through the modern reproduction era. The Winsch card represents the height of pre-WWI German chromolithography and original holiday artwork. Frances Brundage’s contribution shows how established American artists adapted holiday themes for children. The Salem Witch card demonstrates the growing commercialization of local history and holiday traditions. Finally, the Lillian Vernon reproduction reveals how these vintage designs found new life in the mass-market retail era.

Together, they tell a story not just of changing printing technologies and business models, but of the evolving relationship with Halloween itself. From the elaborate artistic productions of the 1910s through the mass-market reproductions of the late 20th century, Halloween postcards have both reflected and shaped how Americans celebrate this fascinating holiday.

The Halloween postcard industry’s journey from German printing houses through American publishers to Asian manufacturers parallels larger trends in American commerce and holiday celebrations. These cards remain valuable historical documents, preserving not just artistic styles and printing techniques, but also the personal connections and social customs of their eras. Whether sent by a teacher to a student in 1913 or purchased as a souvenir in more recent decades, each card represents a tangible link to the holiday and shared heritage.

Alongside any earnest effort to declutter, minimize, or embrace a modest lifestyle, there are delightful rebellions brewing in the corners of our homes, on our bookshelves, and in our hearts. Collecting – postcards, stamps, or any manner of curious objects – is among a great many pastimes that bring us joy.

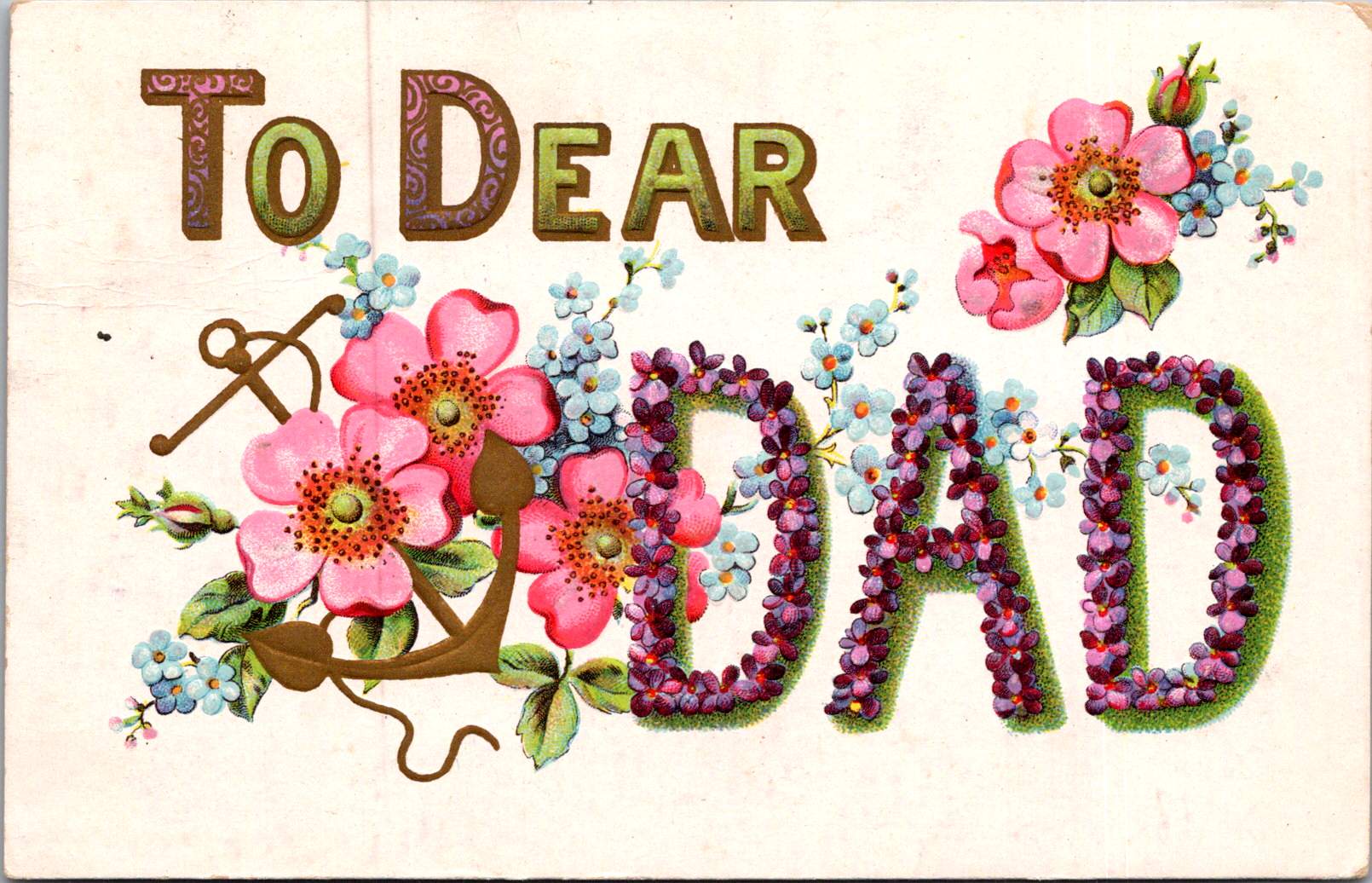

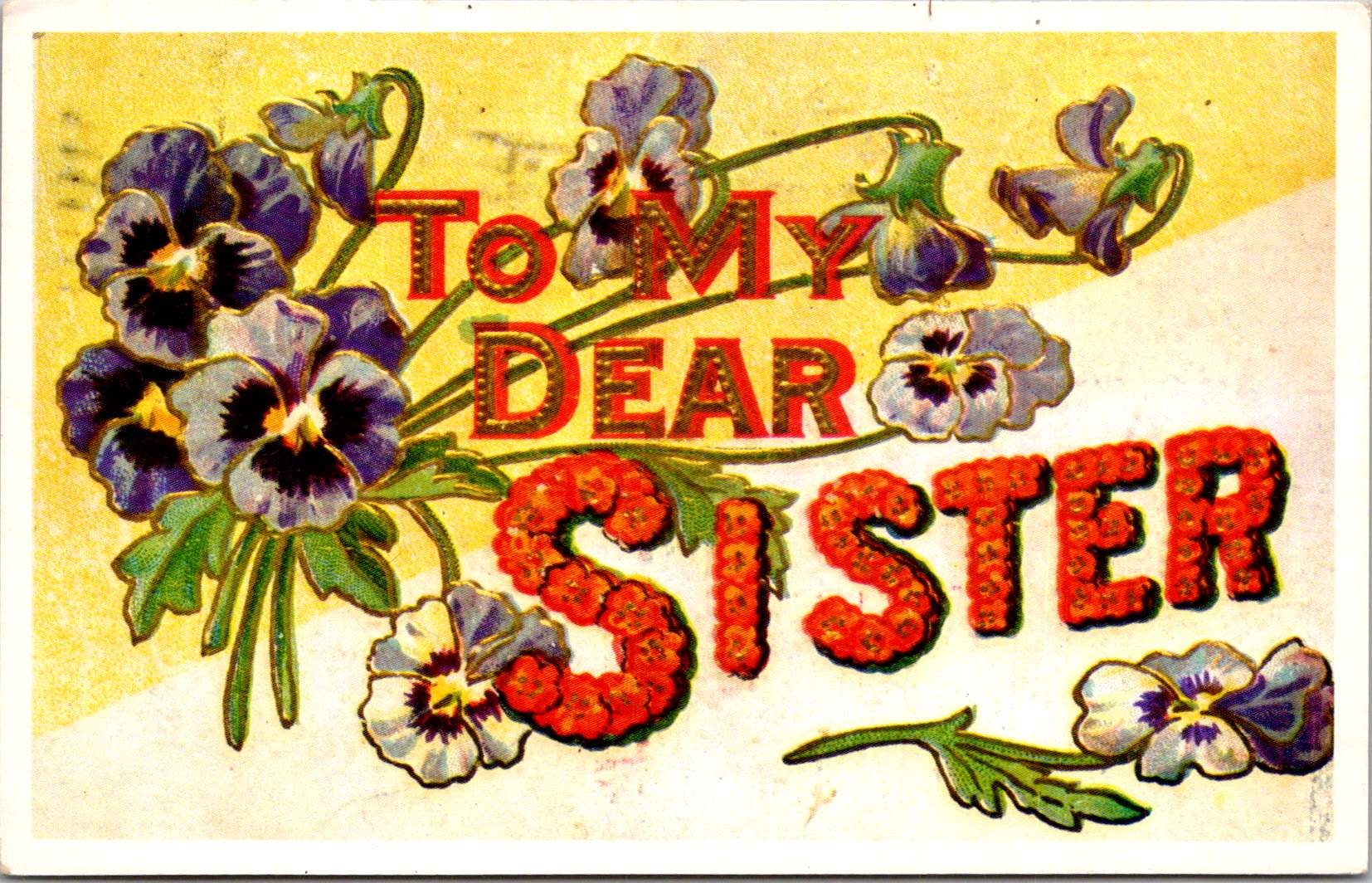

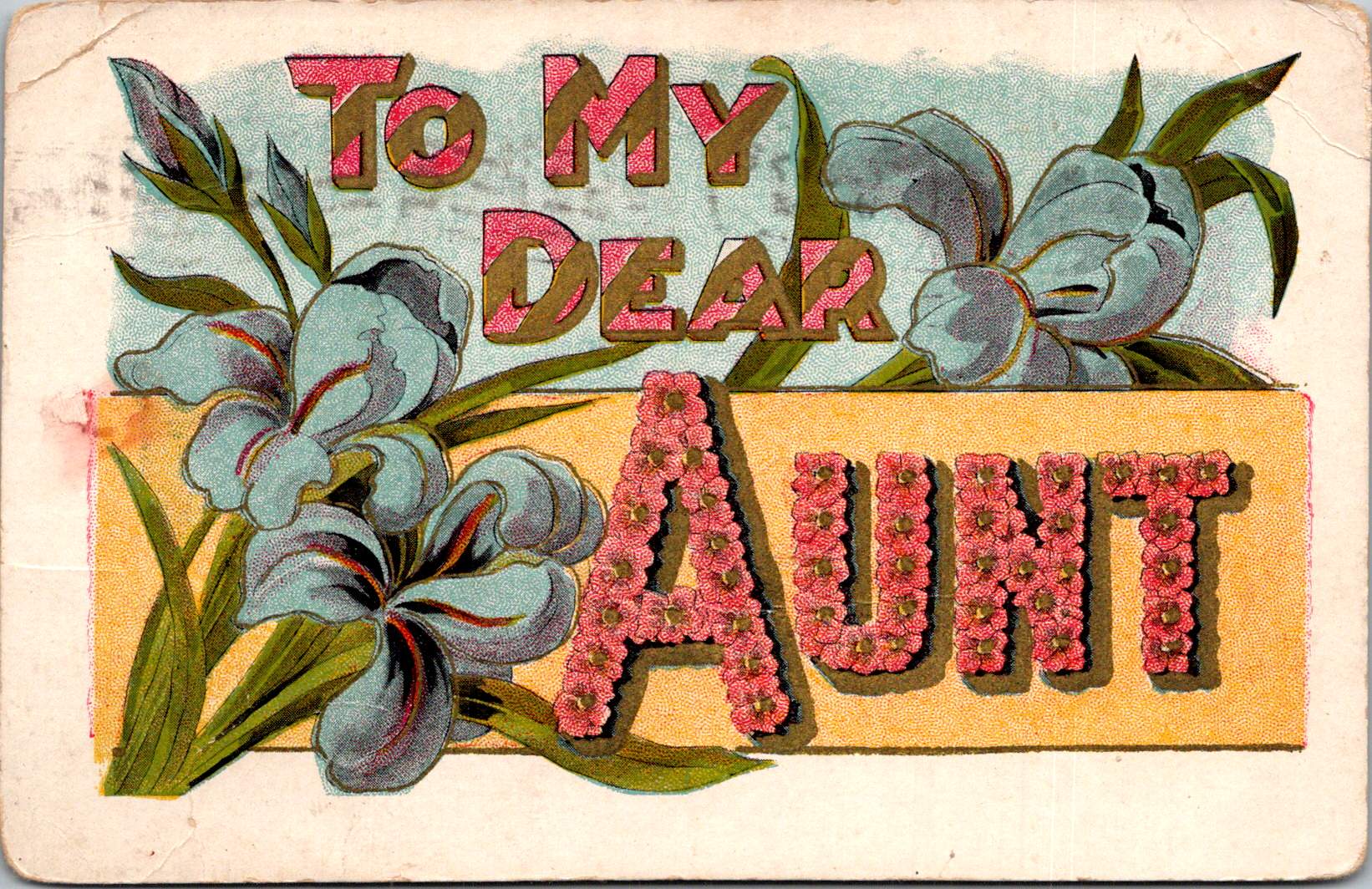

Let’s start with a set of floral letter postcards that captured my heart and imagination recently. For me, they’re time capsules from the Edwardian era, each one a miniature masterpiece of design and sentiment.

Delicate flowers intertwine with bold capital letters, spelling out affectionate greetings to mothers and fathers, aunts and cousins, and more. Blue irises dance around pink and gold lettering, while red roses form the word ‘cousin’ against a dramatic dark background. It’s Victorian drama meets Art Nouveau flair, all condensed into a 3.5 x 5.5 inch rectangle. The colors are vibrant, defying the century they have traveled to meet our modern eyes.

But why do these particular postcards make my collector’s heart skip a beat? It’s not just their undeniable aesthetic appeal, though that’s certainly part of it. They’re windows into history, offering glimpses of a time when sending a beautifully designed card was a primary way of keeping in touch with loved ones. Each handwritten message on the back (like the one postmarked July 10, 1909) is a tiny slice of someone’s life, preserved for over a century.

There’s also the thrill of the hunt. Finding a matching set among thousands of vintage postcards is like piecing together a particularly beautiful puzzle. Each new discovery brings an aha and a sense of completion. It’s a patience game, sure, but the payoff is worth it.

These postcards, with their intricate details and bold typography, have stood the test of time. They’re just as appealing now as they were when they were first printed. Collecting them isn’t just owning pretty objects – it’s a chance to examine, hold, preserve and share a piece of design history, a snapshot of the aesthetic sensibilities of a bygone era.

Collecting is deeply personal. While I pour over century-old postcards, my neighbor friend is curating an ever-expanding collection of adorable bird figurines. He’s particular about it too – they have to be a specific kind, from a specific place, at a specific price point. He watches the bird market, adds to his collection strategically. To a non-birder, it might seem quirky. But watch him arrange his birds, carefully considering where each one fits, and you’ll understand something profound about him: he’s a person who experiences quiet joys.

First and foremost, collecting is about falling in love with something uniquely suited to you. It’s about creating space in your life – physical and emotional – for the things that bring you joy. It’s about curating, admiring, and sharing a part of yourself through the objects you choose to surround yourself with. My friend curates his bird collection, brings them out by the seasons, delightful arrangements that invite family and friends to enjoy, too.

This philosophy extends far beyond postcards and bird figurines. Think about the philatelists out there, losing themselves in the minute details of postage stamps. Each tiny square is a work of art, a nugget of history, a passport to another time and place.

Or consider the sports enthusiasts, their shelves lined with signed jerseys and game-used equipment. For them, these aren’t just objects – they’re tangible connections to moments of athletic glory, to the heroes they admire.

History buffs might seek out Civil War relics or Space Age memorabilia, each artifact a physical link to events that shaped our world. And in our digital age, even contemporary collectibles are thriving. From limited edition vinyl figures to exclusive sneaker releases, people are finding new ways to express their passions through the objects they collect.

What unites all these diverse collecting interests? The deep connection to a particular passion or area of interest that only you can know. Whether it’s a century-old postcard or a just-released collectible figurine, these objects become repositories of personal meaning and cultural significance for their collectors.

Collecting, in its various forms, is just one of many popular ways Americans choose to spend their leisure time. Zoom out for a moment and consider the broader landscape of hobbies and pastimes in the United States.

Reading continues to be a widely enjoyed pastime, with many people diving into both physical books and digital formats. It’s an accessible hobby that caters to diverse interests and can be done almost anywhere.

Gardening has seen a surge in popularity, especially in recent years, as people seek to connect with nature and perhaps grow a bit of their own food. Cooking and baking remain perennially popular, with the rise of cooking shows and online recipes making it easier than ever for people to explore new cuisines and techniques at home.

Exercise and fitness activities, including running, cycling, and yoga, are on the rise as people focus more on health and wellness. Crafting hobbies like knitting, crocheting, and DIY projects have seen renewed interest, offering a creative outlet and the satisfaction of making something by hand.

Photography has become more widespread with the improvement of smartphone cameras, allowing more people to capture and share moments from their daily lives. Not only do I collect floral postcards, I take pictures of beautiful flowers every chance I get!

Hiking and outdoor activities are popular, and of course, sports – both playing and watching – continue to be a major part of American culture and a popular pastime for many.

What drives us to spend our precious free time on these pursuits? The benefits are numerous and far-reaching.

On a personal level, hobbies provide stress relief and relaxation. They offer an escape from daily pressures and can be a form of meditation, helping to reduce stress and anxiety. Many hobbies involve learning new skills or improving existing ones, which can boost self-confidence and cognitive function. They provide a creativity outlet, stimulating imagination and innovative thinking.

There’s also the sense of achievement that comes from completing projects or reaching milestones in a hobby. This can provide a significant boost to self-esteem and overall life satisfaction. Regular engagement in enjoyable activities can help combat depression and improve overall mood. Having a hobby encourages better time management as we carve out time for our interests. And perhaps most importantly, hobbies can become an integral part of our identity, providing a sense of purpose and self-definition outside of work or family roles.

Many hobbies involve communities of like-minded individuals, providing opportunities for social connection and friendship. Engaging with others who share your interests can help develop language, communication and interpersonal skills. Some hobbies, especially those involving arts, crafts, or cuisines from different cultures, can broaden cultural awareness and appreciation.

These pursuits can sometimes lead to unexpected networking opportunities, potentially beneficial for personal or professional growth. Shared hobbies can strengthen family relationships by providing common interests and shared experiences. Many hobbies appeal to people of all ages, facilitating connections across generations. And hobby communities often provide emotional support, advice, and encouragement, fostering a sense of belonging.

Many hobbies, particularly those involving physical activity, contribute to better overall health and fitness. Engaging in hobbies, especially those that challenge the mind, can help maintain cognitive function as we age. Skills learned through hobbies can sometimes translate into valuable job skills or even new career opportunities. Some hobbies can evolve into side businesses or income streams. And perhaps most importantly, hobbies provide a counterbalance to work and other responsibilities, contributing to a more well-rounded life.

So, whether you’re arranging a set of vintage postcards, nurturing a garden, mastering a new recipe, or climbing a mountain, know that you’re doing more than just passing time. You’re engaging in a fundamental human activity, one that brings joy, fosters growth, builds connections, and adds richness to life.

In the end, our collections and hobbies are extensions of ourselves. They reflect our interests, our aesthetics, our values, and our histories. They give us a way to tangibly interact with our passions, to create order and meaning in a chaotic world, and to surround ourselves with objects and experiences that bring us joy and inspiration.

So the next time someone raises an eyebrow at your carefully curated collection of Star Wars figurines, or questions why you spend hours perfecting your sourdough technique, remember this: in pursuing your passions, you’re not just collecting things or passing time. You’re crafting your narrative, preserving memories, expressing your unique identity, and experiencing the quiet (or not so quiet) joys that make life rich and meaningful.

Among all our favorite postcard styles, large letter postcards stand out as evocative artifacts of memory, place, and time. What drives us to collect these small works of design, and what do they reveal about the places we’ve been—or dream of going?

In an age of digital communication and instant photo sharing, there’s something uniquely captivating about large letter postcards. These brightly colored, design-driven place markers have been carrying snippets of the world from person to person – and into collections – for over a century.

Postcard collecting, or deltiology, has been a popular hobby since the late 19th century. What makes postcards so appealing to collectors? For one, they’re relatively affordable and easy to store, making them accessible to collectors of all ages and means. But more than that, postcards offer a unique blend of visual appeal, historical significance, and personal connection.

Humans have been collectors for as long as we know. From prehistoric shells and stones to modern stamps and coins, the act of gathering and preserving token objects is a constant across cultures and eras. But why do we collect?

For collectors of large letter postcards one might choose to focus on cards from a particular state or region, tracing how the depiction of that place changed over time. It’s an exploration of how places have marketed themselves to tourists, of changing aesthetic tastes, and of the evolution of printing technology. Each card is a time capsule, preserving a particular vision of a place at a specific moment in history.

Alternatively, a collector might concentrate on the output of a specific publisher, such as Curt Teich & Co. or Tichnor Brothers, each of which had its own distinctive style. Serious collectors have checklists and databases, and keenly search for highly-prized cards that are known but still not found.

One part of collecting is about finding a comforting order in a sometimes chaotic world. By curating a set of objects, we apply our own structures and meanings onto a small corner of the universe. It’s a way of making sense of the world around us, and also of understanding, exploring, and appreciating our experiences.

Moreover, collections often serve as tangible links to our memories and experiences. Each item in a collection can evoke a specific moment in time, a particular place, or a cherished memory. In this way, our collections become autobiographies of sorts, telling the story of our lives through carefully curated objects.

Collecting also taps into our innate desire for completion. There’s a profound satisfaction in filling gaps in a collection, in finding that elusive item that will make our set whole. This pursuit in itself can become a lifelong passion, providing a sense of purpose and achievement.

Large letter postcards are miniature ambassadors from distant lands, carrying with them not just images but also the tangible evidence of their journey—postmarks, stamps, and handwritten messages.

The hunt for these postcards take collectors to antique shops, flea markets, and specialized postcard shows. Online marketplaces have made it easier to find specific cards, but for many collectors, the thrill of the hunt remains an important part of the hobby.

Each postcard is a snapshot of a particular place at a specific moment, and a unique chance to travel in time. From architecture and fashion to social customs and technological advancements, postcards provide valuable insights into the evolution of society.

The messages scrawled on their backs offer intimate glimpses into personal histories. A hurried “Wish you were here!” or a detailed account of a traveler’s adventures can be just as fascinating as the picture on the front.

At the heart of collecting large letter postcards is our connections to place. Whether we’re collecting postcards from places we’ve visited or from far-flung locales we hope to see someday, each card in our collection represents a connection to a specific geographical location.

This connection to place is a fundamental aspect of human psychology. We are, by nature, territorial creatures, and we form strong emotional bonds with the places that are significant to us. These bonds can be with our hometowns, favorite vacation spots, or even places we’ve only ever dreamed of visiting.

Postcards allow us to carry a piece of these places with us. They serve as physical reminders of our travels, tangible links to the memories we’ve made in different corners of the world. For places we haven’t yet visited, postcards can fuel our wanderlust, providing glimpses of distant lands and cultures.

But our relationship with place isn’t always straightforward. In our increasingly globalized world, many of us find ourselves with multiple place affinities. We might have roots in one city, work in another, and care for family in a third. Postcards offer a way to express and explore these multiple connections to place. A collection might include cards from one’s birthplace, current home, ancestral homeland, and favorite travel destinations, reflecting the complex geography of one’s life and identity.

Large letter postcards hold a special place in the hearts of many collectors. These distinctive cards, which feature the name of a place spelled out in oversized letters filled with local scenes, represent a perfect marriage of place celebration and graphic design.

The heyday of large letter postcards was the mid-20th century, particularly in the United States. This was the era of automobile tourism, when families would pile into their cars for cross-country road trips. Large letter postcards became popular souvenirs, offering a bold, eye-catching way to say “I was here!”

What makes large letter postcards so appealing is their clever integration of text and image. The large letters dominate the card, immediately identifying the location. But within these letters, we find a series of miniature scenes—local landmarks, natural wonders, or typical activities associated with the place. It’s like a visual summary of a destination, condensed into a single, striking image.

From a design perspective, large letter postcards are a triumph of commercial art. They required considerable skill to create, with artists needing to balance the demands of legibility (the place name had to be easily readable) with the desire to include as many local scenes as possible. The result was often a masterpiece of composition and color, with every inch of the card put to effective use.

The style of these postcards evolved over time. Early examples from the 1930s often featured more space between the letters, with scenes depicted in a realistic style. By the 1950s, the letters had typically grown to fill the entire card, with more stylized, graphic representations of local scenes. This evolution reflects broader trends in graphic design and commercial art of the period.

In our era of smartphones and social media, one might expect the appeal of postcards to have diminished. Yet postcards, including modern versions of large letter designs, continue to be produced and collected. Why do these physical artifacts still resonate in a digital world?

Part of the answer lies in their tangibility. In a world where so much of our communication is ephemeral—tweets and status updates that scroll away into oblivion—there’s something deeply satisfying about holding a physical object that has traveled across distance to reach us.

Moreover, the very characteristics that might make postcards seem outdated—their slowness, their limitations—can be seen as virtues. In a world of information overload, the postcard’s constrained format can be refreshing.

For collectors, physical postcards offer a connection to history that digital images can’t quite match. The ability to hold a card that was printed decades ago, to see the handwriting of someone long gone, provides a visceral link to the past that resonates deeply with many people.

Whether we’re talking about vintage large letter postcards or their modern equivalents, these small rectangular pieces of card stock are far more than just souvenirs. They are repositories of memory, snapshots of place, and artifacts of design history.

For collectors, each postcard is a thread in a complex tapestry of place, time, and personal experience. A large letter postcard from Miami might evoke memories of a childhood vacation, appreciation for mid-century graphic design, and curiosity about how the city has changed since the card was printed.

In a world where our connections to place are increasingly complex and multi-layered, postcard collections allow us to map our personal geographies. They give tangible form to our memories, our travels, and our dreams of future journeys.

Moreover, in their celebration of specific places, postcards—and large letter postcards in particular—remind us of the rich diversity of the world. In an era of globalization, where many fear a homogenization of culture, these cards stand as colorful testimony to the unique character of different locations.

So the next time you come across a rack of postcards in a gift shop, or spot a vintage large letter card in an antique store, take a moment to appreciate these small works of design. They are more than just pretty pictures or quaint relics. In their own small way, they help us make sense of our place in the world—and isn’t that, after all, what collecting is all about?

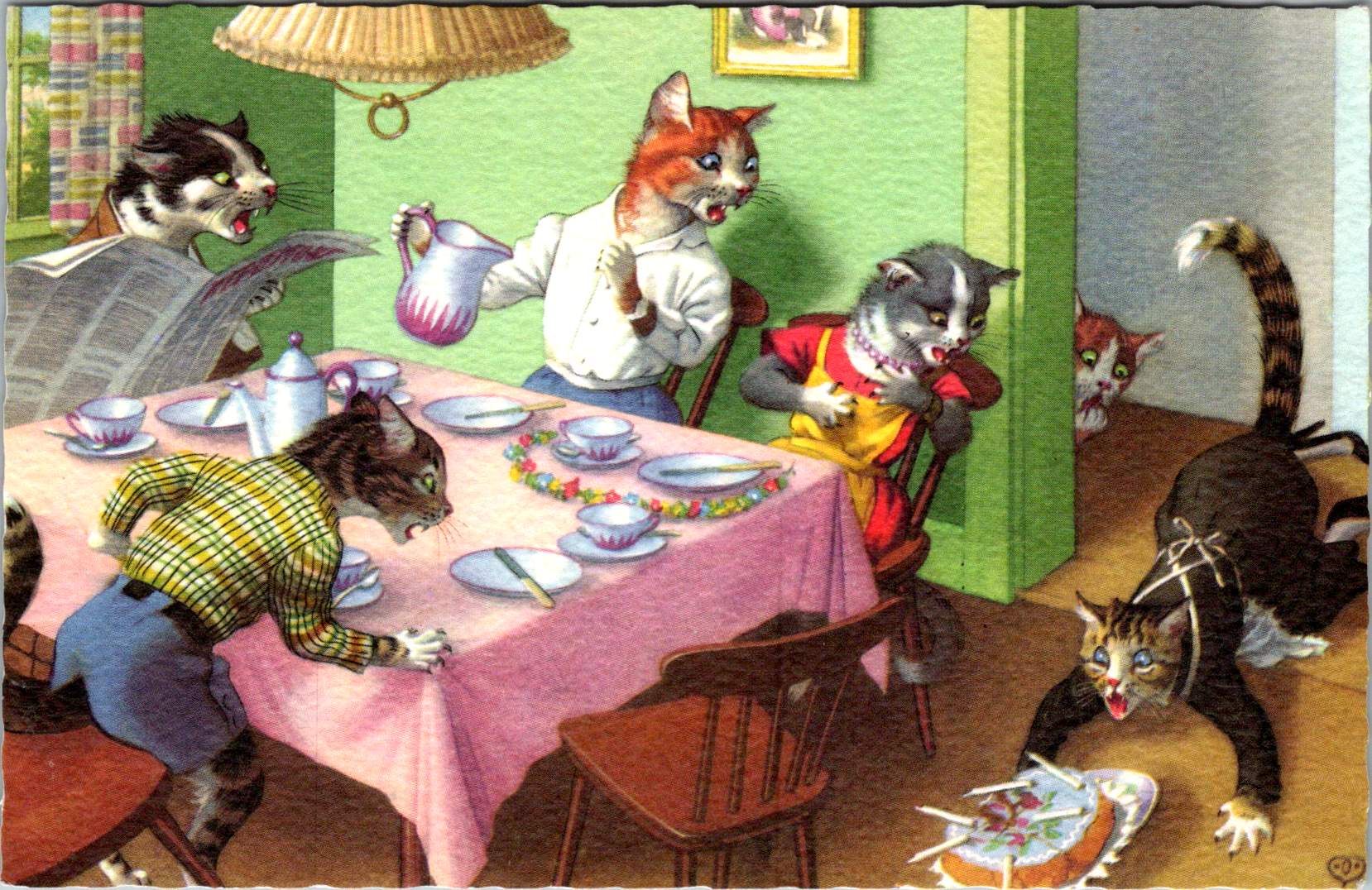

Mainzer Cats graced millions of postcards in their heyday. But the man whose name became synonymous with these charming, anthropomorphic animals was not their creator.

In the colorful world of mid-20th century postcards, a peculiar case of mistaken identity has long intrigued collectors and art enthusiasts. The charming, anthropomorphic cats that graced millions of postcards, known widely as “Mainzer Cats,” have a secret. Alfred Mainzer, the man whose name became synonymous with these whimsical felines, was not their creator. This tale of artistic attribution, commercial success, and enduring popularity offers a fascinating glimpse into the intersection of art, commerce, and our enduring love of cats.

At the heart of this story are two men: Eugen Hartung, a Swiss artist born in 1897, and Alfred Mainzer, an American publisher. Hartung, the true artist behind the beloved cat illustrations, worked in relative obscurity, while Mainzer, through a twist of fate and business acumen, became the name associated with these popular images.

Eugen Hartung developed his artistic skills early in life, studying at the School of Applied Arts in Zürich. His background as a lithographer and graphic designer laid the foundation for his later work, which would prove ideal for reproduction on postcards and other printed materials. In the 1940s, perhaps inspired by the need for joy and whimsy in the aftermath of World War II, Hartung began painting his signature anthropomorphic animal scenes.

Hartung’s cats, engaged in human activities ranging from attending school to getting married, captured the imagination of viewers with their charm and humor. These illustrations, painted in delicate watercolors, featured cats with expressive faces and human-like postures, placed in everyday scenarios that resonated with people’s daily experiences.

Enter Alfred Mainzer, a businessman and publisher based in Long Island City, New York. Alfred Mainzer Inc. specialized in greeting cards and postcards. With a keen eye for marketable content, Mainzer imported the Belgium-printed postcards to distribute to the American market.

This business decision would lead to both the widespread popularity of the cat postcards and the confusion surrounding their creator. As the postcards gained fame in the United States, they became known as “Mainzer Cats” or “Alfred Mainzer postcards.” Over time, many people assumed Alfred Mainzer was the artist behind these charming illustrations.

The misattribution persisted for years, with Mainzer’s name becoming increasingly associated with the artwork. Meanwhile, Hartung, described by some sources as a quiet and modest individual, who was recognized in his native Switzerland, but not beyond.

This case of mistaken identity highlights the complex relationship between artists and publishers in the world of commercial art. While Mainzer’s business acumen brought Hartung’s work to a broader audience, it also inadvertently obscured the original artist’s identity. Today, collectors and art historians are working to properly attribute the artwork to Hartung while acknowledging Mainzer’s role in popularizing these images in the United States.

The popularity of Hartung’s cat postcards, published by Mainzer, can be attributed to several factors. Their charm and humor, depicting cats in comical human situations, resonated with viewers. The illustrations were relatable, mirroring familiar human experiences through a feline lens. They also evoked a sense of nostalgia, particularly as they gained popularity in the 1950s and 1960s.

From a practical standpoint, postcards offered an affordable way for people to enjoy and share art. The wide variety of scenes depicted made the postcards highly collectible, with enthusiasts eager to acquire different designs. Moreover, the enduring popularity of cats as pets and subjects in art likely contributed to the appeal of Hartung’s work.

While Hartung’s cats gained unique popularity through Mainzer’s postcards, the feline form has long been a subject of study for artists. Throughout history, artists have turned their attention to cats, each bringing their unique style and perspective to feline representation.

One of the most famous cat artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was Théophile Steinlen. This Swiss-French Art Nouveau painter became renowned for his cat illustrations, particularly his iconic “Chat Noir” (Black Cat) poster. Steinlen’s work, while more realistic and less anthropomorphic than Hartung’s, shared a focus on cats in daily life settings. Both artists imbued their feline subjects with personality and character, though Steinlen’s approach was less whimsical than Hartung’s.

Louis Wain, an English artist active in the same period, is another notable figure in the world of cat art. Wain’s early works bear some stylistic similarities to Hartung’s, featuring anthropomorphic cats engaged in human activities. However, Wain’s style evolved dramatically over his lifetime, influenced by his mental health. His later works became increasingly abstract and psychedelic, diverging significantly from the style of artists like Hartung. Fans will enjoy the 2021 movie starring Claire Foy and Benedict Cumberbatch, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain.

Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita, a Japanese-French painter of the early 20th century, was renowned for his drawings and paintings of cats. Foujita’s cats, often white with delicate, fine lines, showcased a different aesthetic from Hartung’s more colorful and active felines. Nonetheless, both artists shared a deep appreciation for the feline form and its expressive potential.

In the realm of fine art, artist Suzanne Valadon included cats in portraits and still life compositions. Valadon’s realistic depictions contrast with Hartung’s more stylized approach, yet both artists recognized the cat’s potential as a compelling subject.

The tradition of anthropomorphic animal art, of which Hartung’s work is a part, has roots that stretch back centuries. In Japan, for instance, Kuniyoshi Utagawa created many woodblock prints featuring cats in humorous or fantastical situations during the 19th century. While working in a very different medium and cultural context, Utagawa’s depictions of cats in unexpected scenarios share thematic similarities with Hartung’s work.

More recently, contemporary artists like Ai Weiwei have incorporated cats into their work, demonstrating the enduring appeal of felines as artistic subjects. Ai’s Cats and Dogs series of ceramic sculptures offers a modern take on feline representation, far removed from the whimsical postcards of Hartung yet part of the same long tradition of cats in art.

The story of Eugen Hartung and Alfred Mainzer illustrates the complex interplay between art and commerce. Hartung’s artistic talent and Mainzer’s business acumen combined to create a cultural phenomenon that has endured for decades.

Hartung’s legacy lies in his charming, whimsical artwork that continues to delight viewers today. His anthropomorphic cats, with their human-like expressions and activities, offer a unique blend of humor and familiarity. The enduring popularity of these images speaks to Hartung’s skill in capturing the essence of both feline and human nature in his illustrations.

Mainzer’s legacy, on the other hand, is one of successful commercialization and distribution. By recognizing the potential of Hartung’s work and bringing it to a wider audience, Mainzer played a crucial role in popularizing these images. The “Mainzer Cats” became a recognized brand, even if the attribution was misplaced.

Today, both Hartung and Mainzer are remembered in the world of postcard collecting and vintage art enthusiasts. Efforts to correctly attribute the artwork to Hartung have increased in recent years, bringing deserved recognition to the original artist. At the same time, the Mainzer name remains closely associated with these beloved postcards, a testament to the company’s role in their popularization.

Despite the passage of time, Hartung’s cat postcards, often still referred to as Mainzer postcards, continue to captivate collectors. The market for these vintage pieces remains active, with enthusiasts ranging from dedicated deltiologists (postcard collectors) to cat lovers and nostalgia enthusiasts.

The appeal of these postcards extends beyond their original format. The enduring charm of Hartung’s designs has led to reproductions on various products, including calendars, notebooks, and home decor items. This expanded market has introduced Hartung’s whimsical cats to new generations of admirers.

Interestingly, some collectors and historians value these postcards not just for their artistic merit, but for their depiction of mid-20th century social norms and daily life, albeit in a whimsical, anthropomorphized form. This adds an educational dimension to their collectible status.

The enduring interest with cats that fueled the popularity of Hartung’s postcards is far from a thing of the past. In fact, felines have only grown in popularity as artistic subjects and cultural icons in the digital age.

Social media platforms have become showcases for cat-related art and imagery. Instagram accounts dedicated to cat art boast millions of followers, while viral cat videos and memes have become a staple of internet culture. This digital proliferation of cat content echoes the widespread appeal of Hartung’s postcards in a new medium.

Contemporary artists continue to find inspiration in felines. From traditional mediums like painting and sculpture to digital art and animation, cats remain a popular subject. Artists like Vanessa Stockard have gained recognition for their whimsical style that echoes some of the charm found in Hartung’s work. Stockard’s most famous work mimics the Old Masters while inserting her cat, Kevin, into traditional compositions.

The popularity of cats in art has also translated into commercial success in various industries. Cat-themed products, from clothing to home decor, are widely available and popular. This echoes the commercial success of Mainzer’s postcards, demonstrating the enduring marketability of feline-inspired art.

In the world of high art, cats continue to make appearances. Exhibitions dedicated to feline art have been held in major museums and galleries around the world. For instance, the Japan Society in New York hosted an exhibition titled “Life of Cats” in 2015, showcasing cats in Japanese art from the 1615 to 1868.

The story of Eugen Hartung and Alfred Mainzer, and the beloved cat postcards they brought to the world, is more than just a tale of mistaken identity. It’s a narrative that touches on the nature of artistic creation, the power of commercial distribution, and the enduring appeal of a subject that has captivated humans for millennia.

Hartung’s artistic vision, brought to a wide audience through Mainzer’s business acumen, created a cultural phenomenon that continues to resonate today. The charming, anthropomorphic cats that populate these postcards speak to our enduring fascination with felines and our ability to see ourselves reflected in their actions and expressions.

As we unravel the mystery of the Hartung-Mainzer cats, we gain insight into the complex world of commercial art and the ways in which attribution can become confused over time. Yet, we also see how the power of the art itself can transcend issues of authorship, creating a legacy that endures for decades.

In our current era, where cat memes reign supreme and feline influencers command millions of followers, the popularity of Hartung’s cats seems almost prophetic. From fine art galleries to internet forums, our fascination with cats as artistic subjects continues unabated.

The Hartung-Mainzer story reminds us of the timeless appeal of art that captures the whimsy and charm of everyday life, whether through the lens of anthropomorphic cats or other creative interpretations. It stands as a testament to the power of art to connect with people across generations, and the enduring allure of our feline friends in the realm of human creativity.

Pick out a Hartung-Mainzer Postcard for yourself or a friend!