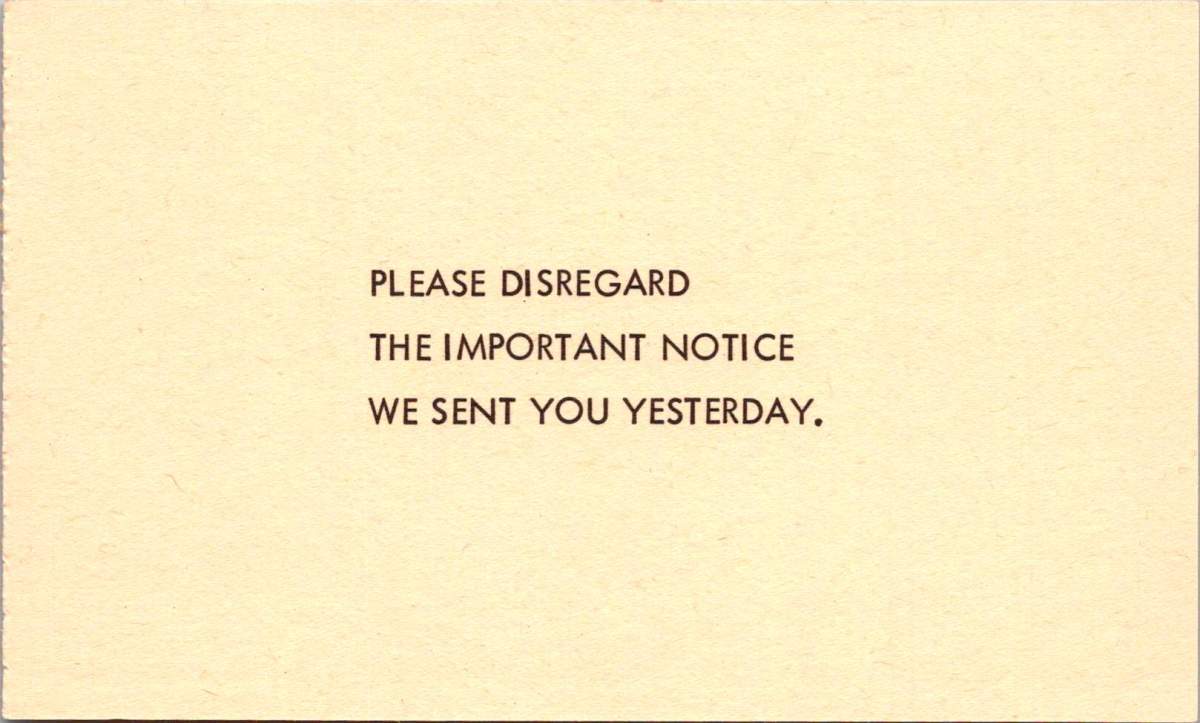

This vintage postcard, simply titled “Training for Politics,” captures a brutal honesty that resonates well on days when the world stinks. A lone cowboy, shovel in hand, flinging horse manure (the raw material for politics). Of course we see the effort, but it’s also hard to miss the explosive spray of debris frozen mid-flight.

There’s something uniquely comforting about humor that doesn’t try to brighten our mood but instead acknowledges the absurdity of our circumstances. When we’re struggling, the last thing most of us want is forced positivity or silver linings. We want recognition that yes, this is indeed a pile, and yes, someone is actively shoveling more of it.

On the surface, it’s a simple visual gag – politics is bullsh*t. But dig deeper (pardon the pun), and you’ll find a more nuanced observation about the nature of political discourse and human coping mechanisms.

Dark humor serves as a pressure release valve for the soul. It’s the linguistic equivalent of opening a window in a foul-smelling room. It doesn’t solve the problem, but it makes it more bearable. When we can laugh at the darkness, we’re not surrendering to it – we’re claiming it, owning it, transforming it into something we can manage.

Someone looked at a man shoveling manure and saw not just the physical act but its perfect metaphorical parallel to politics. They recognized that sometimes the most profound truths come wrapped in the most pungent packages. That’s what gallows humor does – it finds the universal in the awful, the communal in the catastrophic.

This postcard’s enduring relevance speaks to another truth about dark humor: it ages well. While more wholesome jokes may grow stale, gallows humor often becomes more poignant with time. Perhaps because human suffering, like political maneuvering, remains remarkably consistent across generations. The tools may change, but the essential nature of the job remains the same.

In our current era of carefully curated social media positivity and inspirational quote overdose, there’s something refreshingly honest about this image. It doesn’t try to inspire or uplift. It simply says, “Here’s what’s happening, and it stinks.” Sometimes, that acknowledgment is more comforting than a thousand motivational posters.

For those of us having one of those days – when the pile is knee deep – this anonymous cowboy becomes an unlikely patron saint of perseverance. Not because he’s rising above his circumstances or transforming them into something beautiful, but because he’s right there in the muck, doing what needs to be done, probably muttering colorful commentary under his breath.

The image reminds us that sometimes the healthiest response to life’s challenges isn’t to seek the bright side but to acknowledge the darkness with a wry smile and a few choice words. There’s solidarity in shared cynicism, comfort in the collective cry. It’s the silent nod between people who recognize that while we can’t always clean up the mess, we can at least make a postcard about it. If nothing else, it gives future generations something to laugh darkly about while dealing with their own problems.

It’s no good to make light of serious situations, but it helps to find the light-heartedness within them. Even if it’s just the glint of sun off a well-worn shovel.