As landscapes, last week’s real photo postcards (RPPC) asked for nothing. Trees, frozen roads, animals burrowing in snow—they floated free of context. We could easily appreciate them without knowing where they might be.

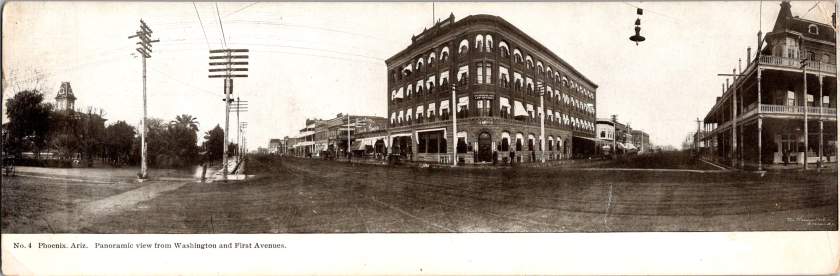

Buildings are different. A structure says someone decided, planned, risked, and accomplished. They hauled materials, drove nails, painted trim. Buildings demand explanation in ways that hills might easily demure.

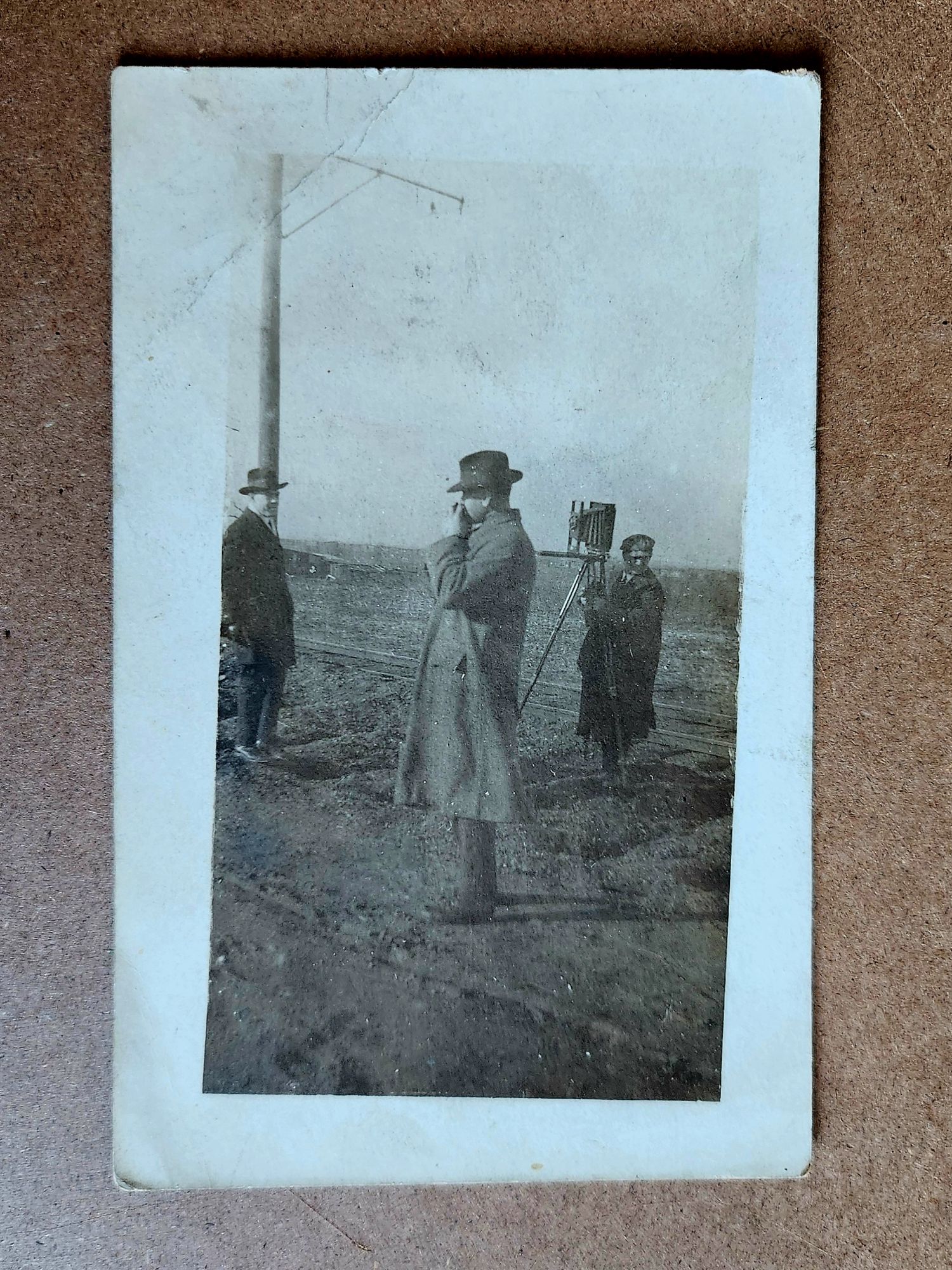

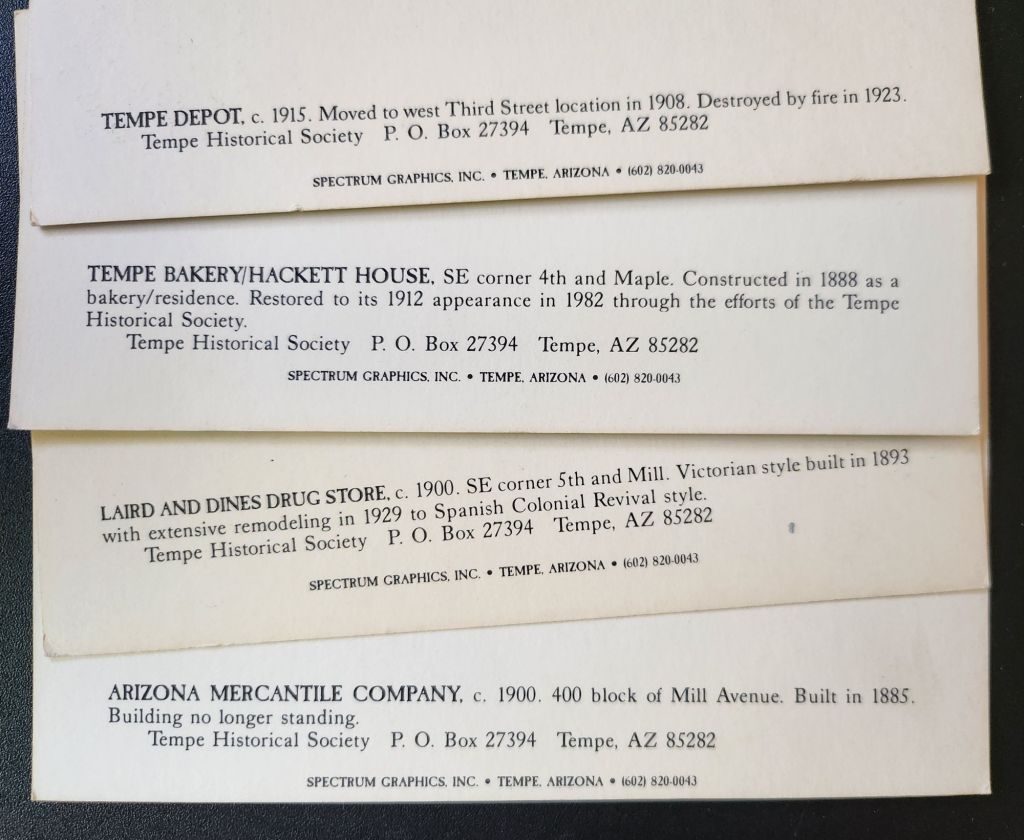

Reading postcards slowly reveals patterns. The undivided back means pre-1907. The real photo process suggests a local photographer, or maybe an itinerant professional documenting a place too remote to the reach of commercial postcard companies. Paper stock, indicia, stamps and cancellation, faded handwriting and previous labeling, even image placement and crop—these technical details narrow the place possibilities.

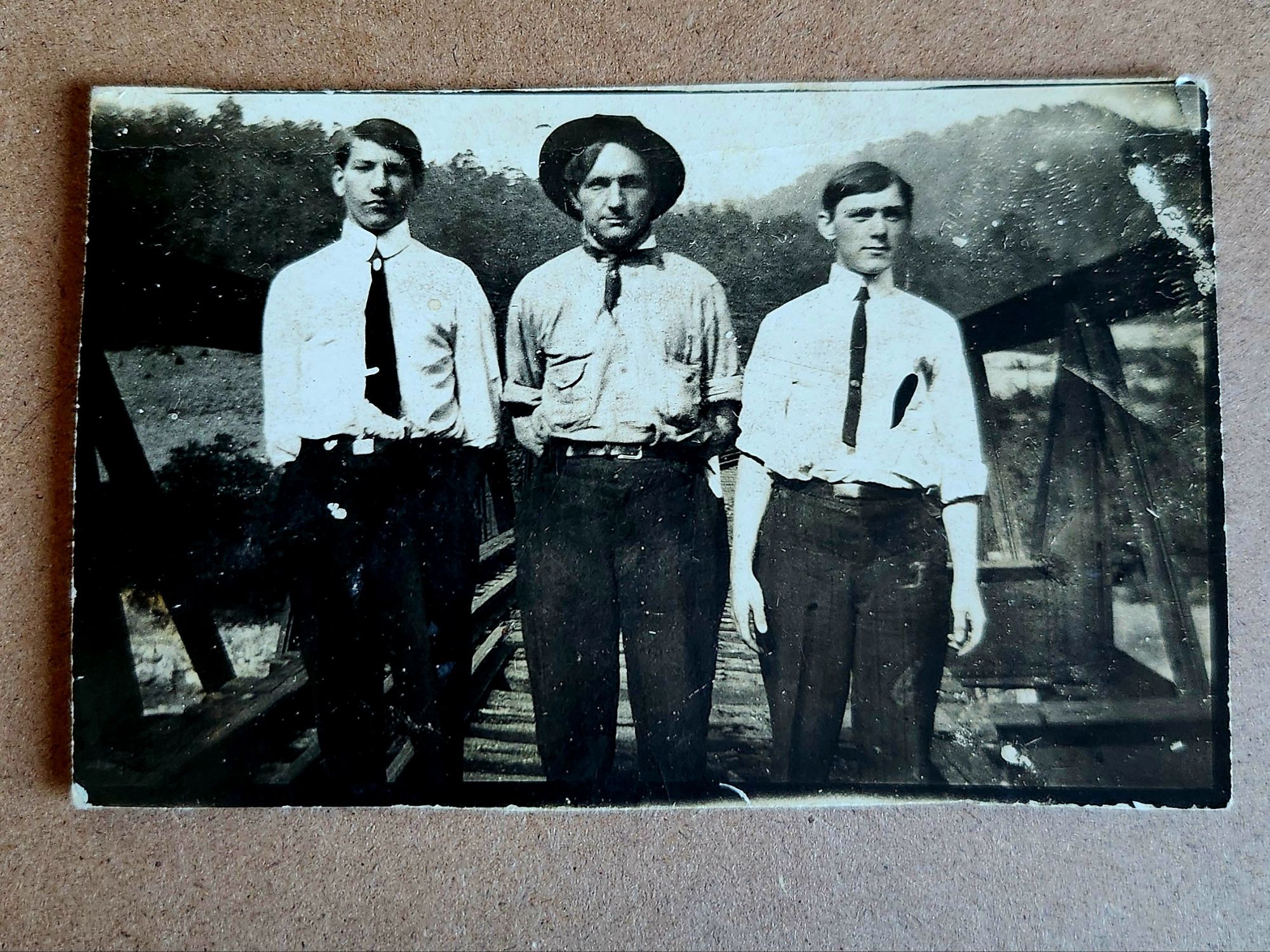

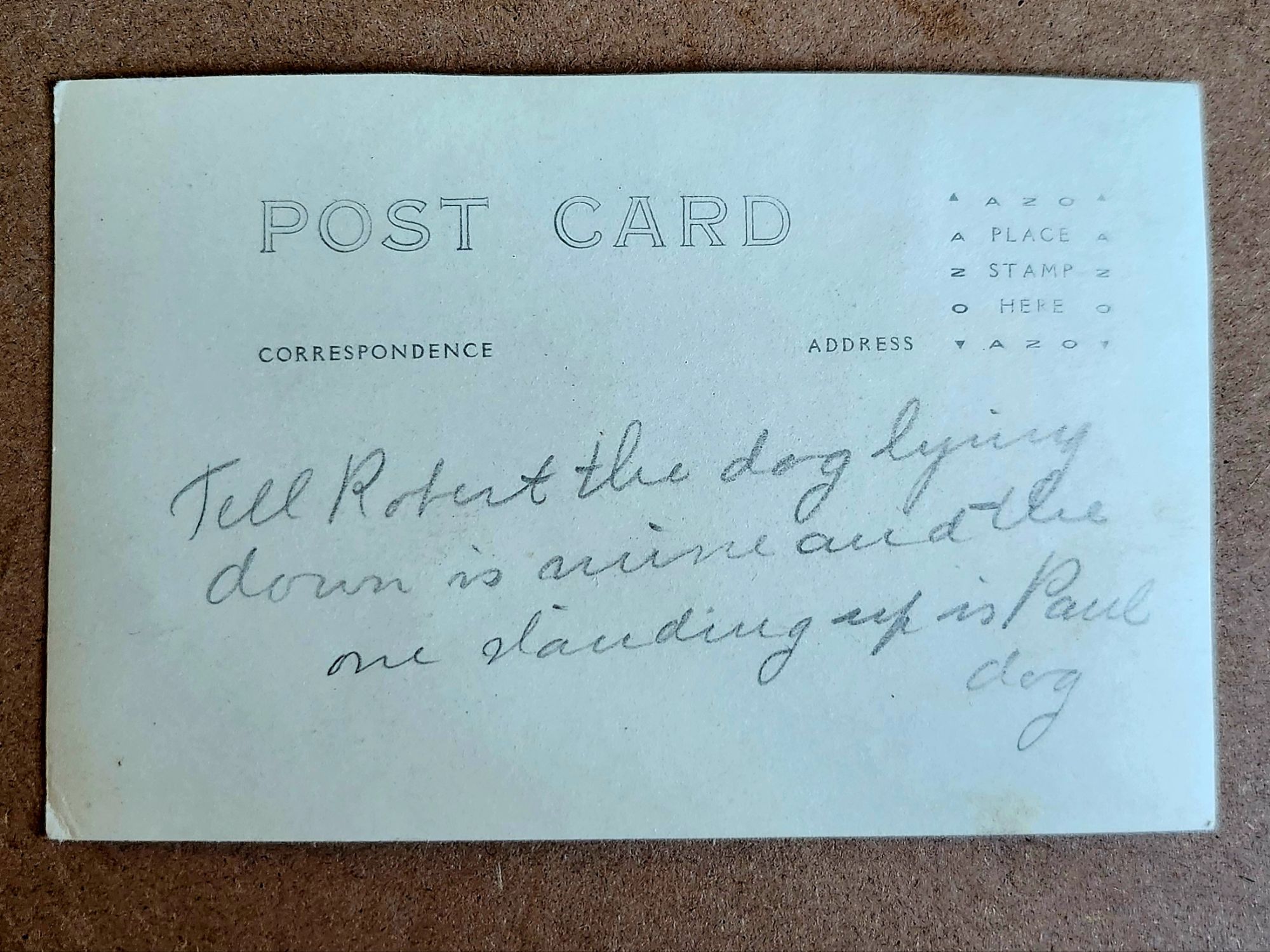

But they don’t yet answer another question: Who are Robert and Paul?

Tell Robert the dog lying down is mine and the one standing up is Paul dog

What We Might Know

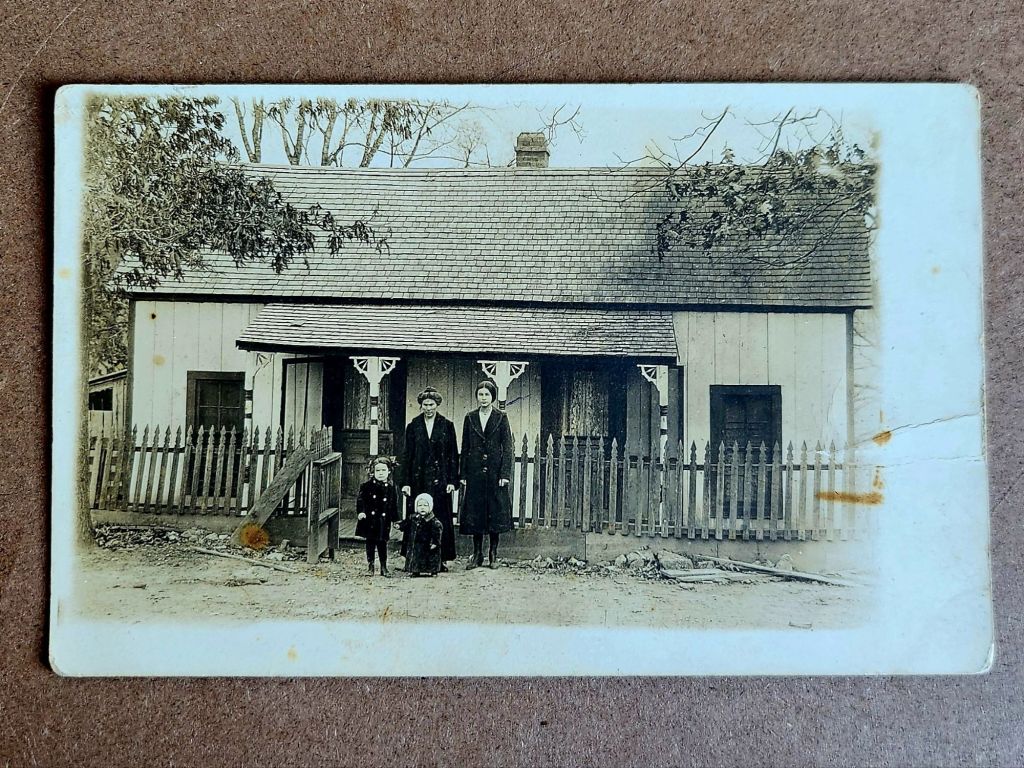

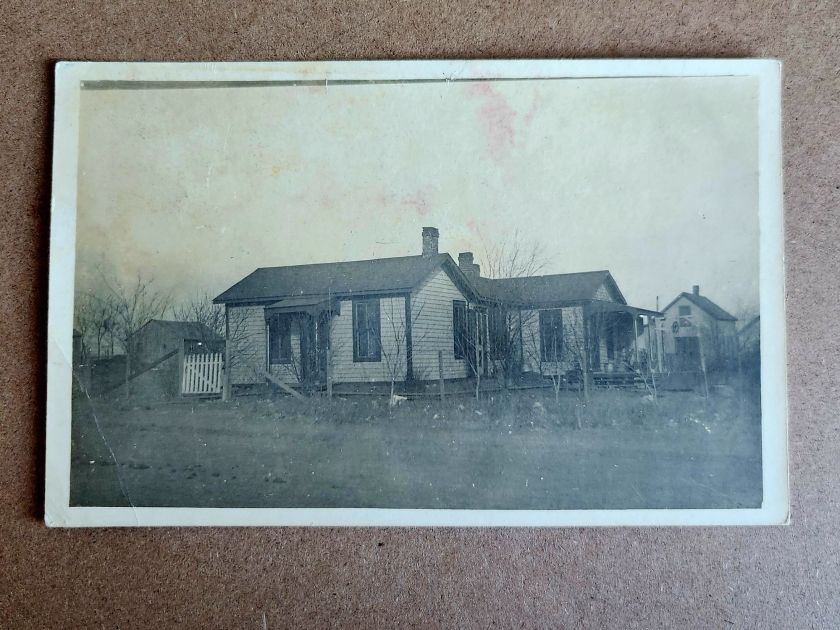

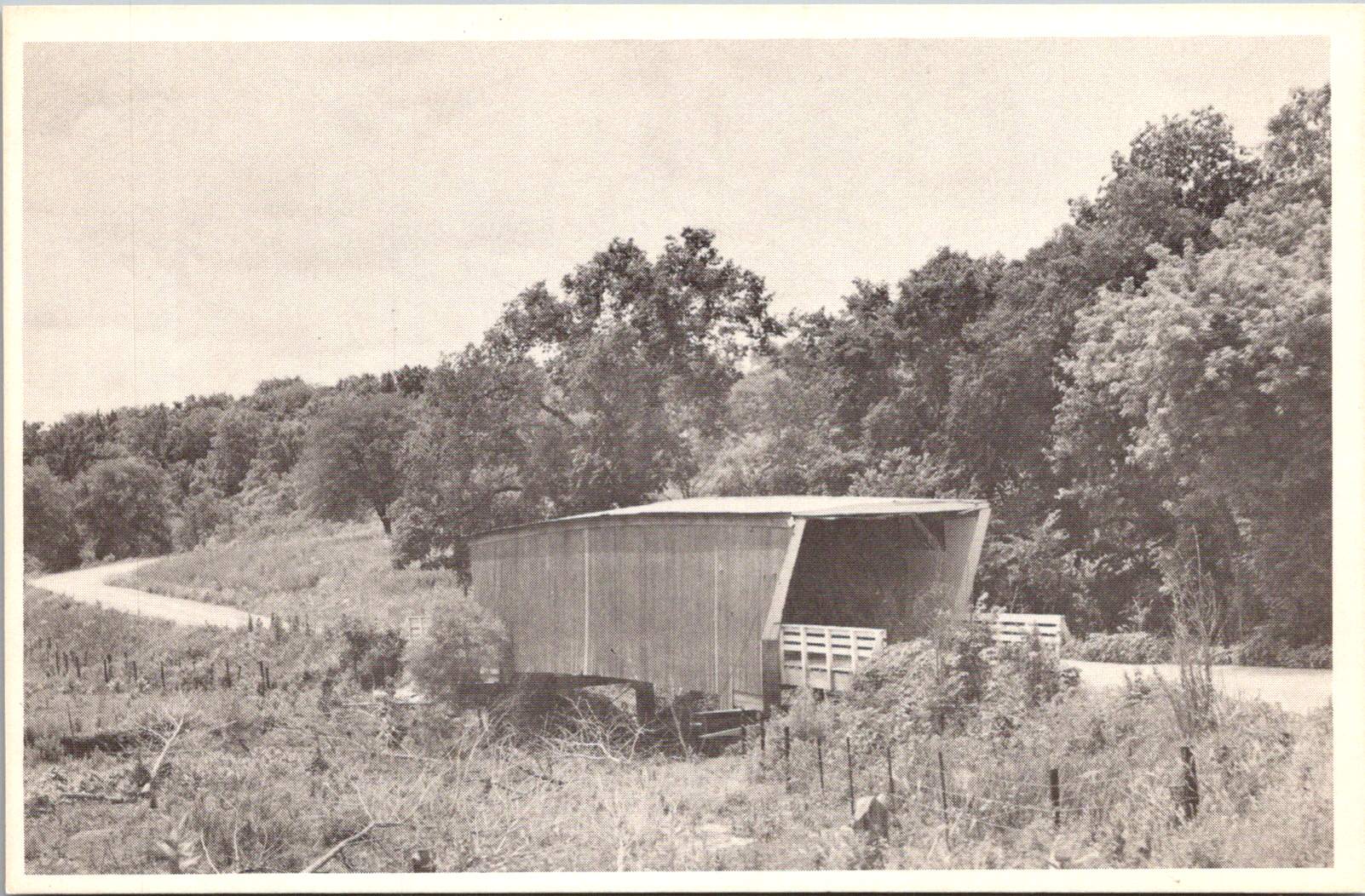

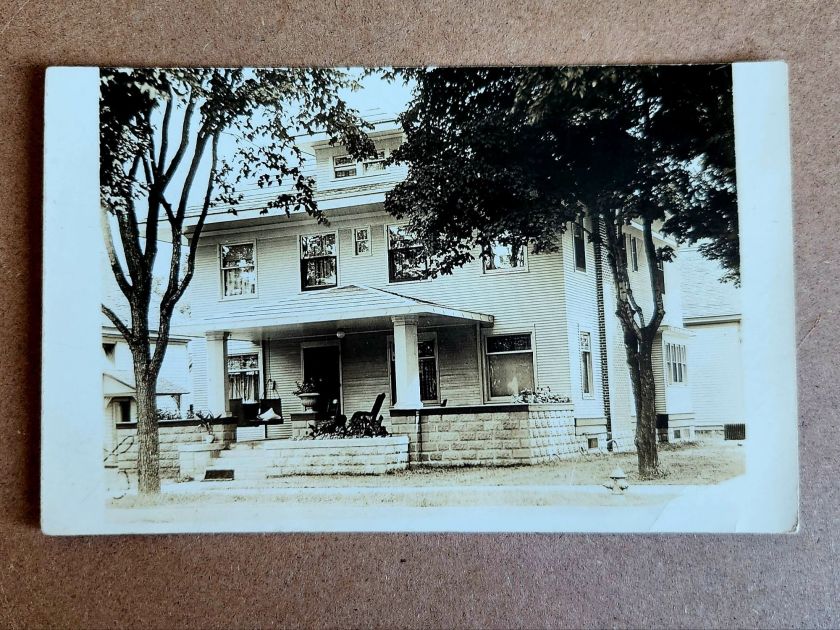

A two-story house with a generous porch is carefully centered in one photograph. Mature trees in the foreground. Curtains hang in the windows. Someone lived here and wanted to show their pride. Or, was it for sale?

The architectural details offer more clues. Clapboard siding, stone or brick foundation, decorative porch elements—not fancy, but intentional. It seems to be in a neighborhood with sidewalks. In an era between 1900-1920, somewhere in the Midwest or West judging by lot size. Also, a fire hydrant.

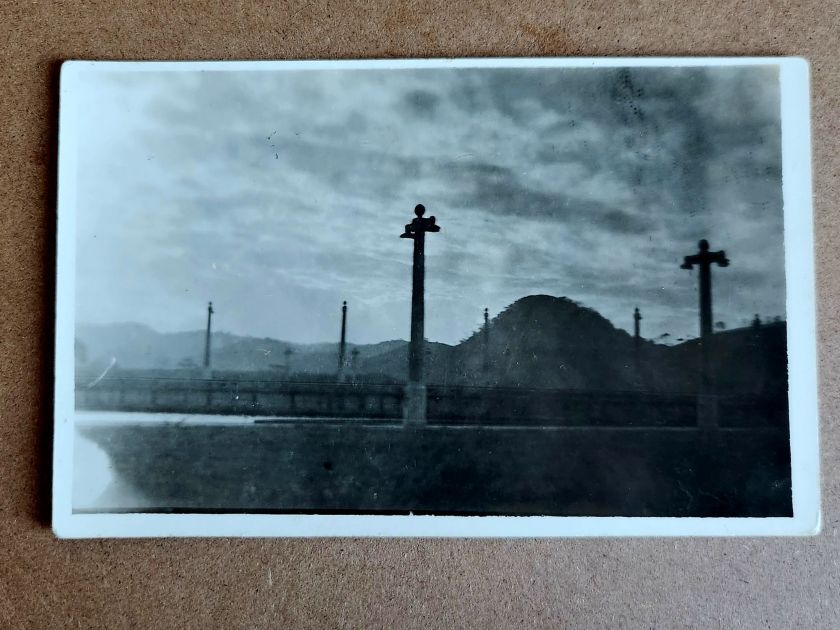

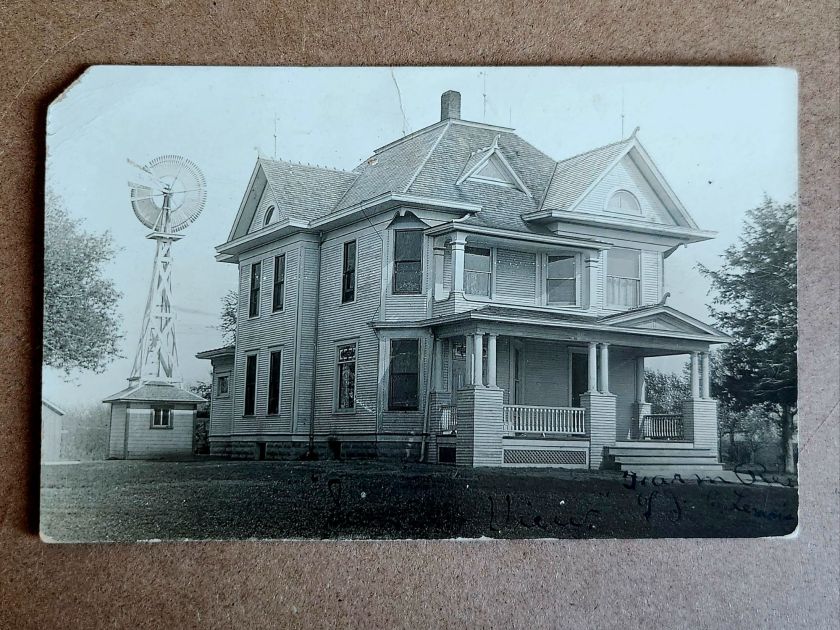

The windmill in another image dates itself. Windmills were an important utility and industry, and that style had a particular era. The house beneath it—elaborate Queen Anne with corner turret, ornamental shingles, and ornate columns—speaks to aspiration. Someone had big plans. This is visible evidence. When and where becomes roughly recognizable.

But, the people who stood on that porch remain absent and enigmatic. Who were they? What is happening here? A creative tension is mounting between the realm of evidence and the pull of story.

Sensing Stories

Two women stand in front of McMann Boarding House wearing identical striped dresses. The building is simple—board and batten, minimal trim, the kind of structure that goes up first and fast in a growing place.

The photograph has a vertical tear, the exposure is bad, and time has degraded it. But the sign remains legible: McMann Boarding House. Finally, a name.

Who was McMann? Who are these women? Employees? Vacationers? The photo is both casual and deliberately staged. What might the matching dresses mean? Pride? Subjugation?

Reading their faces, we fill in the narrative, almost immediately and sometimes inescapably. Relationships, motivations, futures take shape unbidden. This is exactly what we both invited and warned of last week—making it up. Always dangerous, sometimes worthwhile.

The impulse to story is nearly irresistible. A name on a building. Two women in matching dresses. The space around the postcard lights up. Are these their stories, or our own, or a magical projection that folds time?

When the Past Chats Back

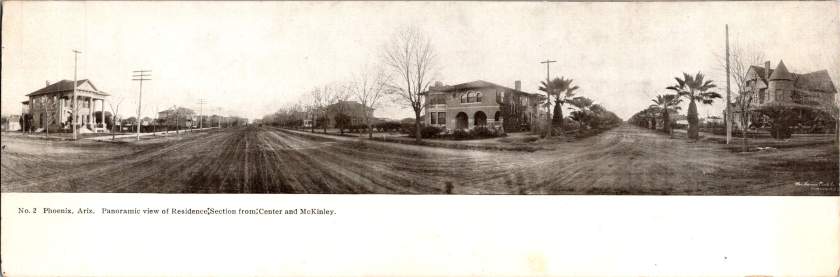

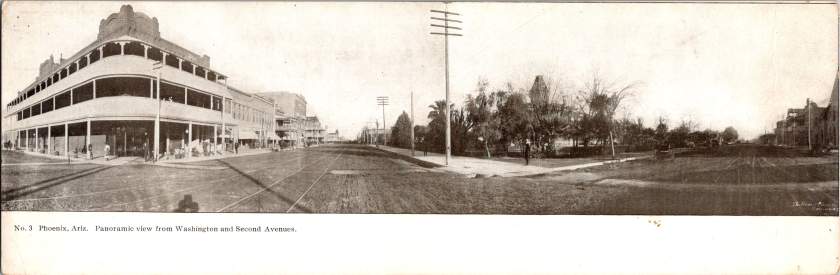

Shuffling the stack, several cards in this collection start speaking to one another. Same photographic quality. Same paper stock. Similar landscape—flat, spare, newly broken. And most telling: similar structures in states of becoming.

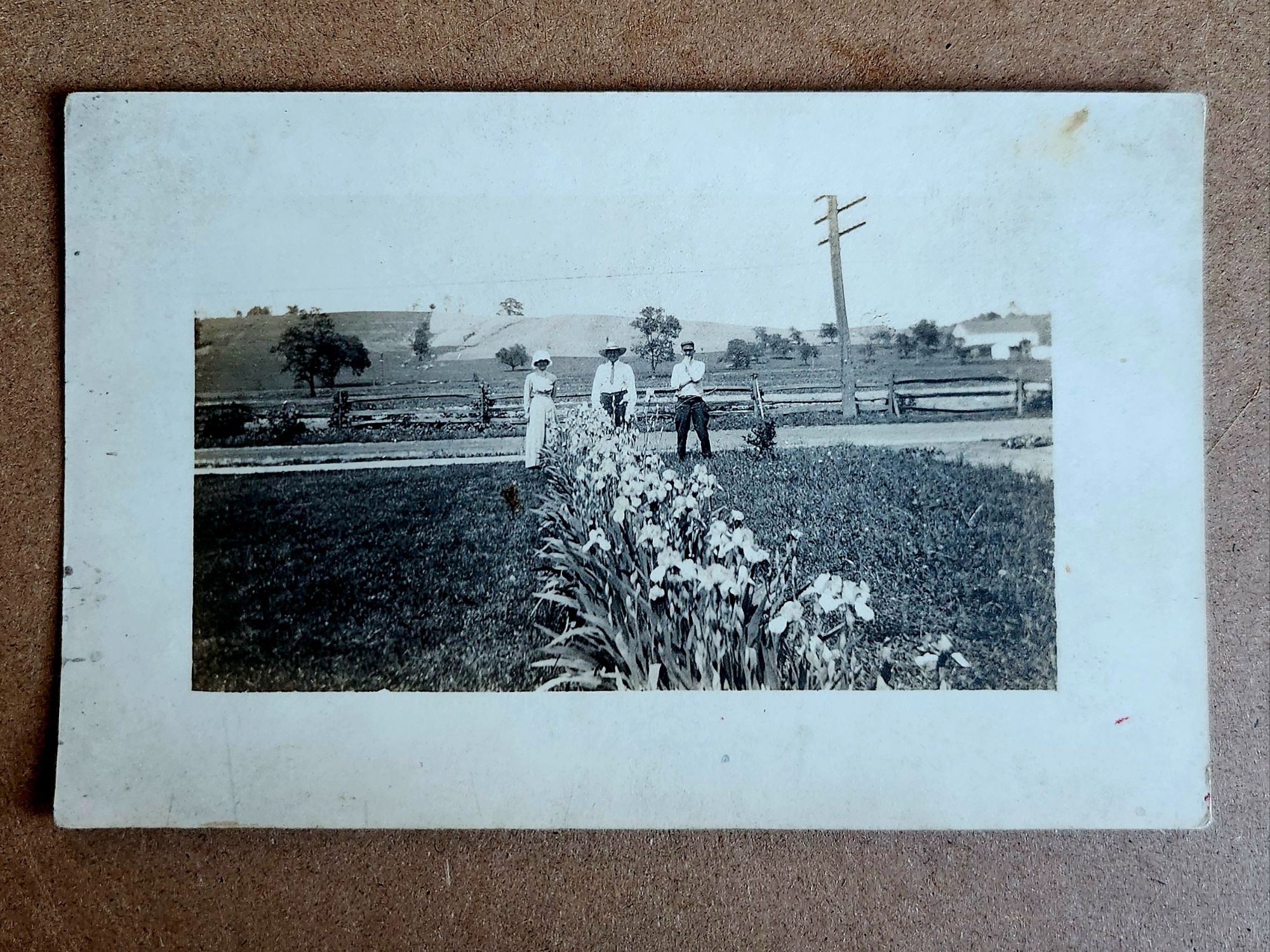

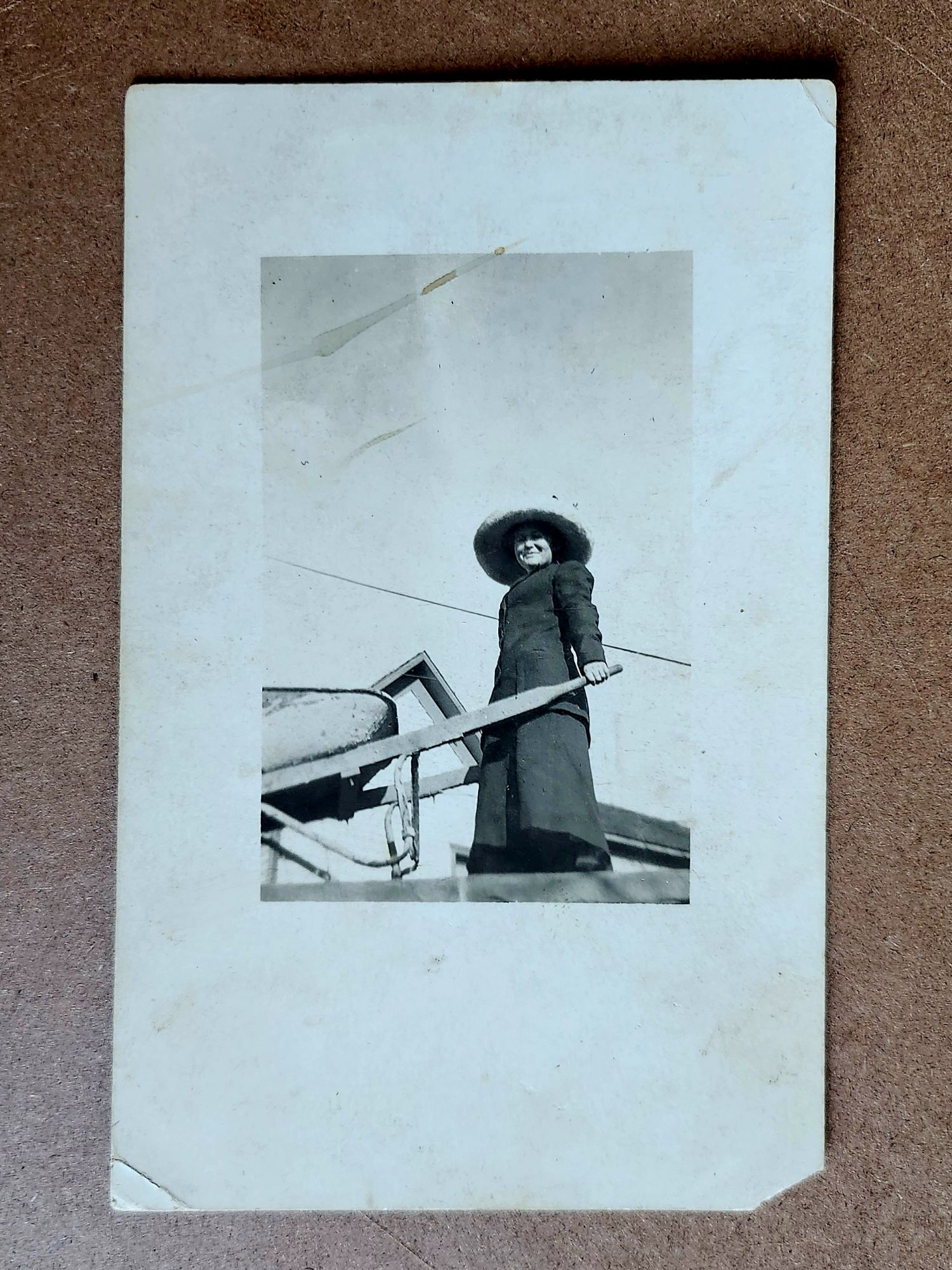

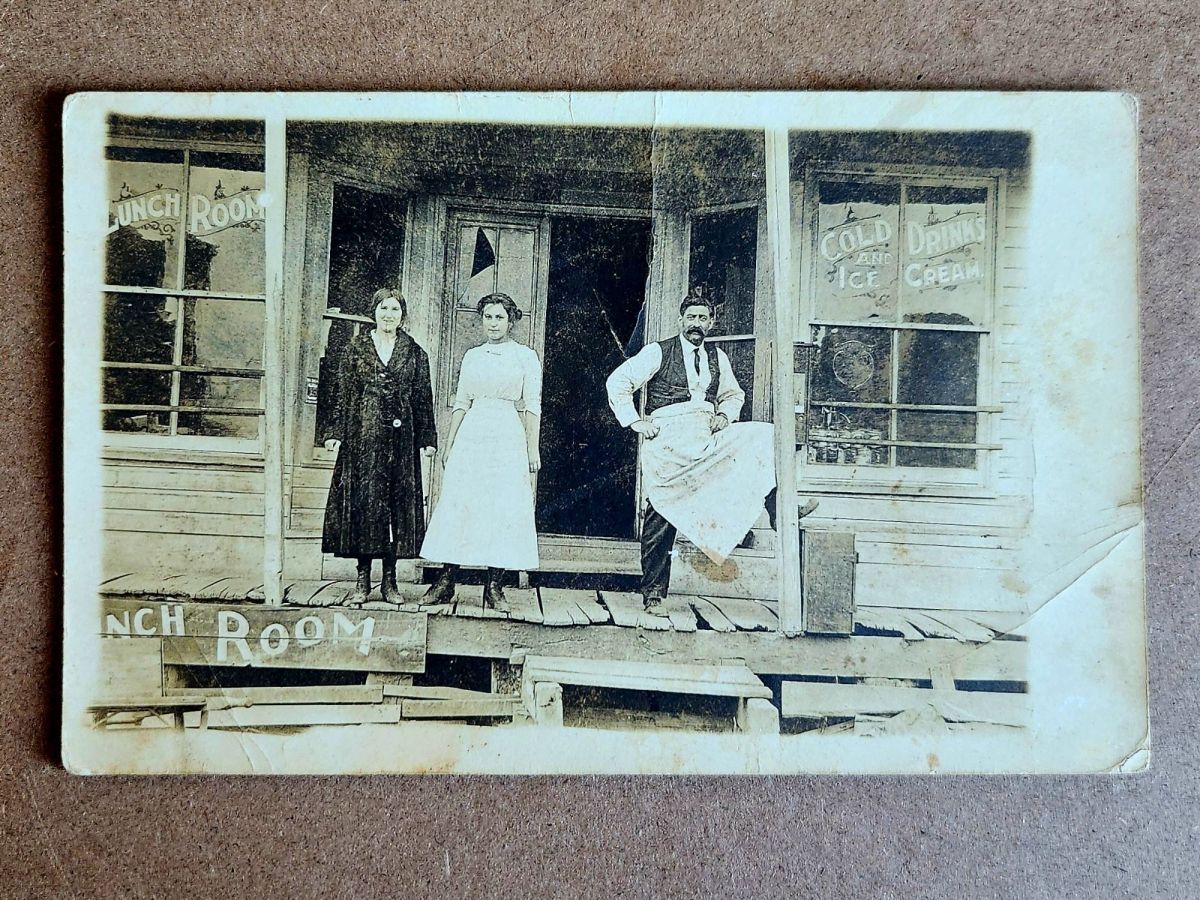

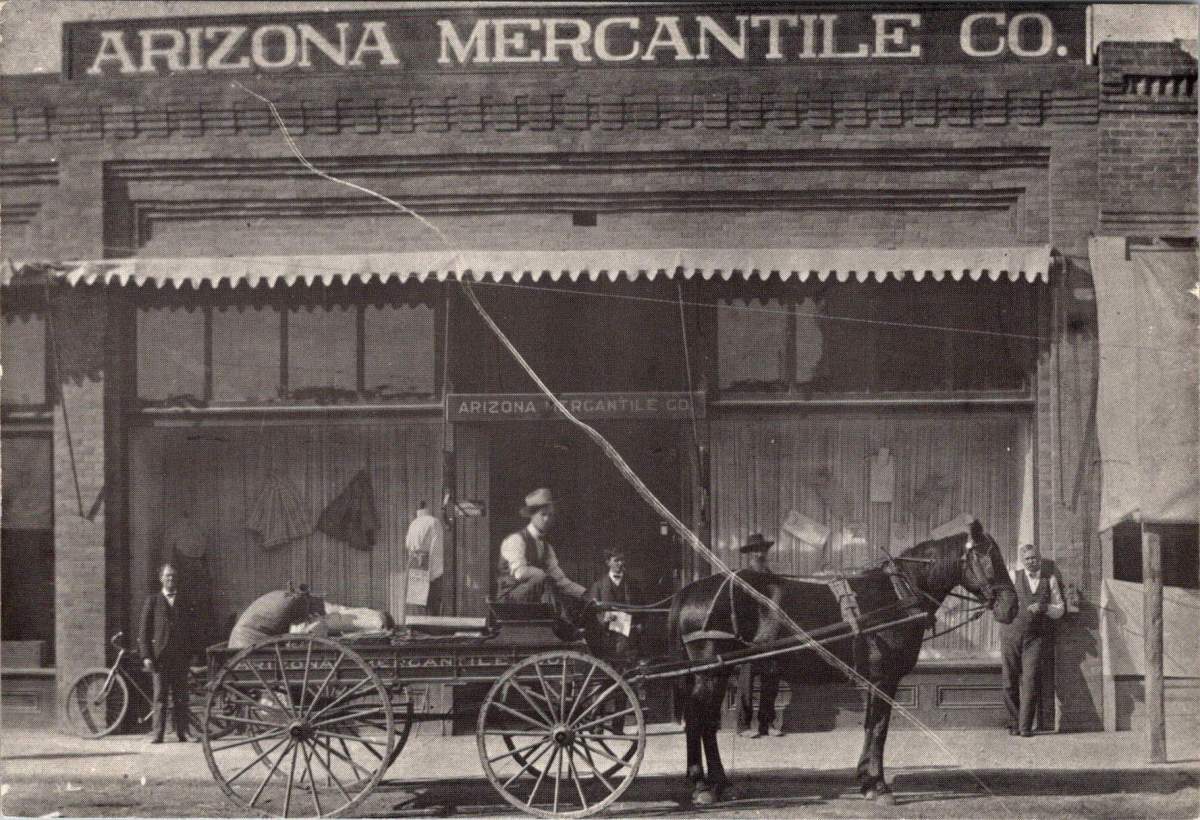

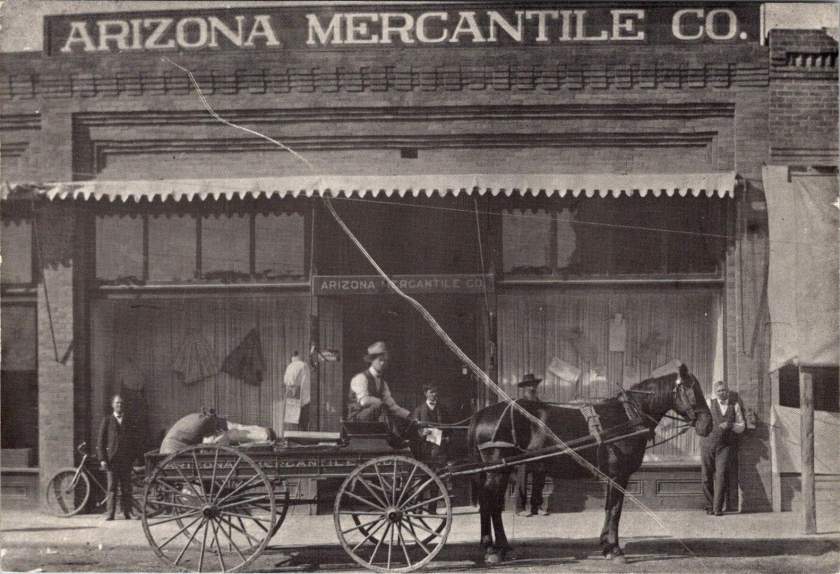

Laid out together, the pattern emerges. Houses with stone foundations and wraparound porches. An elaborate Queen Anne with a windmill. McMann Boarding House with its two women in matching stripes. A lunch room with an immaculately vernacular grand porch. Best-dressed proprietors standing proud. A girl and her horse, bare buildings behind her. A picnic under the canopy of a large tree.

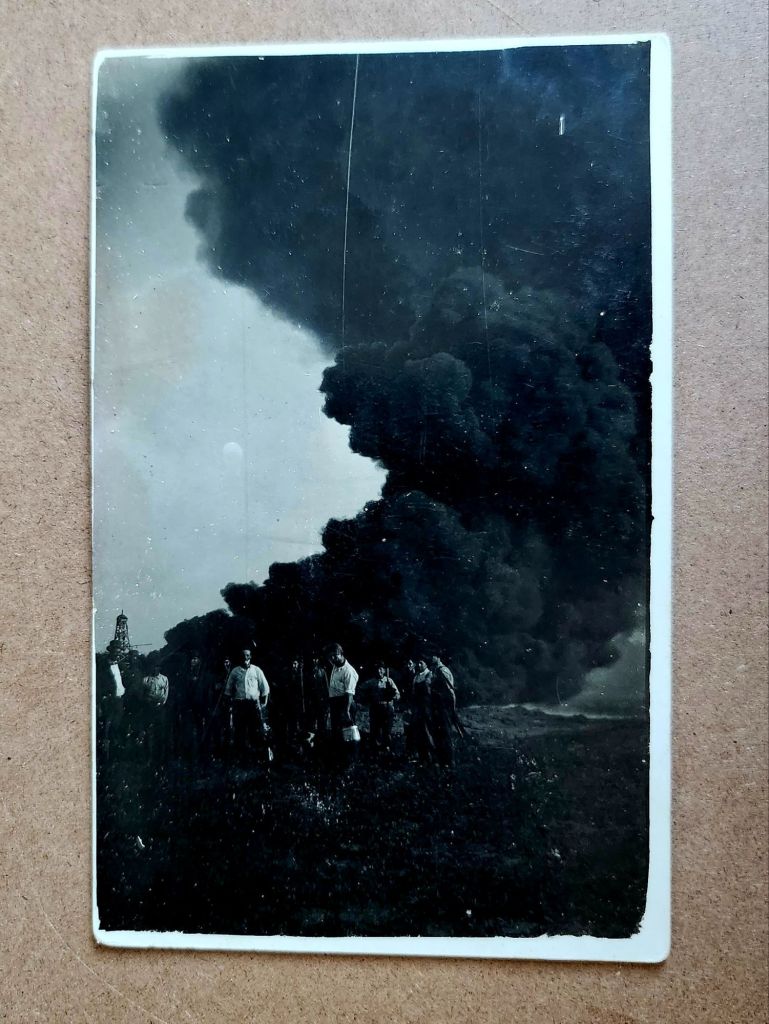

Also, a massive plume of black smoke billowing skyward, an oil derrick to the left, eight or nine men grinning toward the camera. The photograph stops everything cold. They struck liquid gold. A triumph worth documenting. Fine lines of the plumes etching through the darkest black.

These eleven images are a cluster from the same story—a town emerging around oil. Homesteaders and entrepreneurs arriving in a place that may have been open prairie five years earlier. Building homes, businesses, infrastructure for both industrial productivity and social life. Documenting the process with real photo postcards, for themselves or to send East. Their message: we have arrived safely and are in luck.

From Here to Now

This is a founding, the moment a place began and the stakes changed. These aren’t isolated buildings anymore and oddly they seem less like photos, too. We know there is a community taking shape and the evidentiary questions multiply. Who were they, by name? What brought them here? Did this place survive or vanish?

And harder, deeper, more consequential questions: Who lived here before? What animals and habitats were displaced? What did the derricks do? For them, and also to us.

Boom town logic. Extraction economy. Infrastructure dependencies and family injuries inherited. Cultural degradation, and environmental costs still being paid. This isn’t quaint history. This is the beginning of something we’re grappling with today.

Suddenly our imaginative stories contract and we now seek facts. The boarding house proprietor’s daily life can be imagined, but not separated from a place built on oil speculation. The architectural ambition of that Queen Anne deserves appreciation, but it went up in a town that might have lasted ten years or a hundred, depending on the wells. The buildings aren’t innocent, and we are implicated.

More in Store

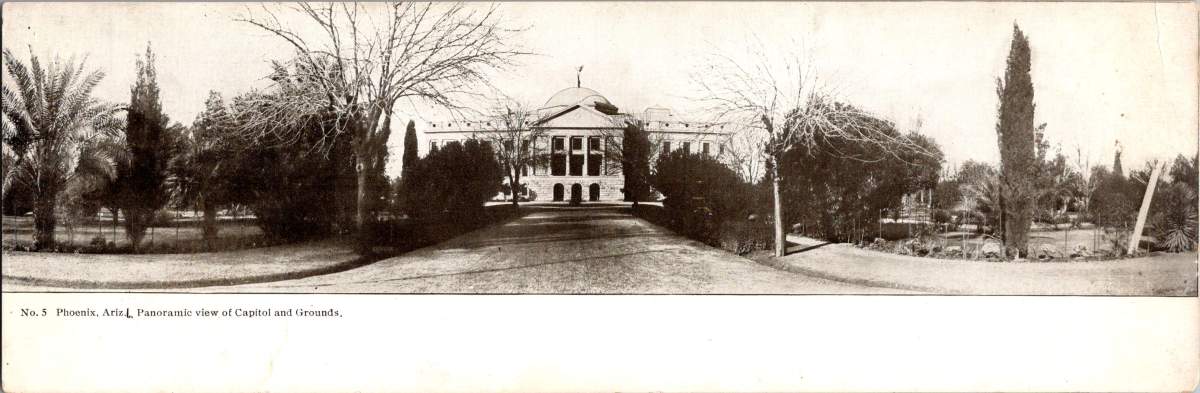

Another stack of postcards might be related to this cluster—similar age, similar style, possibly the same region, likely at later dates. And then a few unrelated ones, probably European based on the architecture.

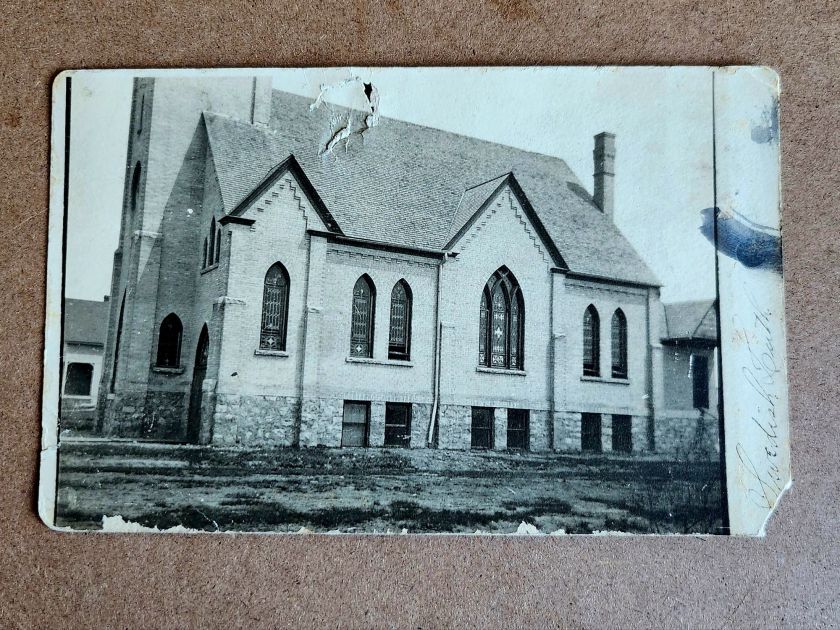

Not every fragment connects or resolves. Some buildings will remain singular, their stories unrecoverable. Churches and homes, beautiful structures, carefully photographed. Loved locally today as a memory or a ruin, perhaps.

Not everything needs a narrative. Some images can just be enigmatic. Evidence of care, of craftsmanship, of a moment someone thought worth preserving. These evocative details lead to fiction, which makes its own case for history and the preservation of minute detail.

But this cluster won’t let go. They connect to another stack, and soon we’ll know more. Next week we’ll meet the people themselves, looking back at us.