On an autumn morning in 1935, Eleanor Roosevelt walked alone through the woods at her personal retreat in Hyde Park, New York. The First Lady had just returned from touring poverty-stricken areas in West Virginia, where families struggled to survive the Great Depression.

These morning walks were her ritual for processing the weight of what she witnessed in her tireless work. The woods, she would later write, helped her find the clarity needed to transform empathy into action.

Decades earlier, John Muir had written to a friend. His words would become a rallying cry for the American conservation movement, adorning everything from park posters to backpack patches.

The mountains are calling and I must go.

But what exactly is this call we hear from nature? Why do we feel drawn to preserve wild spaces and to protect them for future generations? And what happens to us when we answer that call?

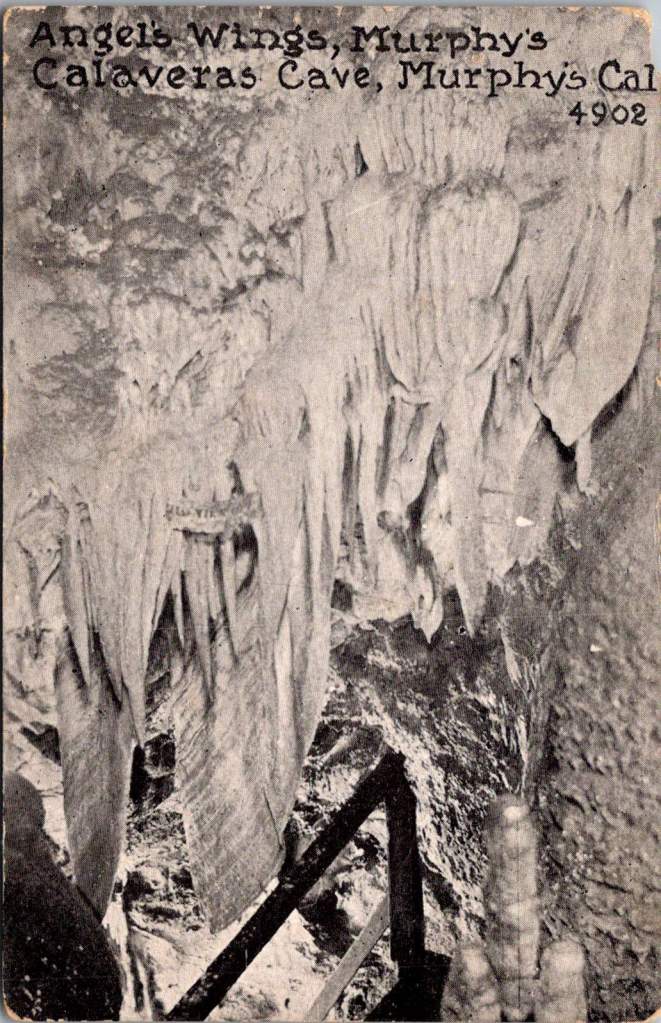

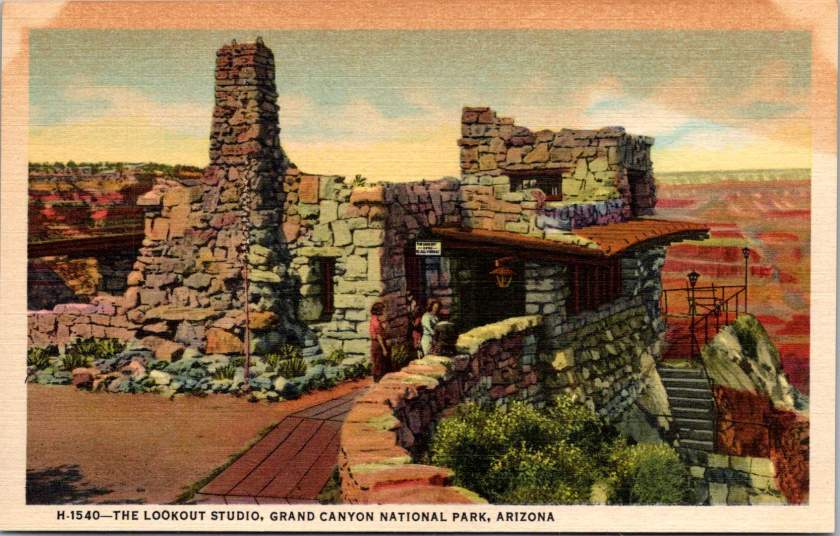

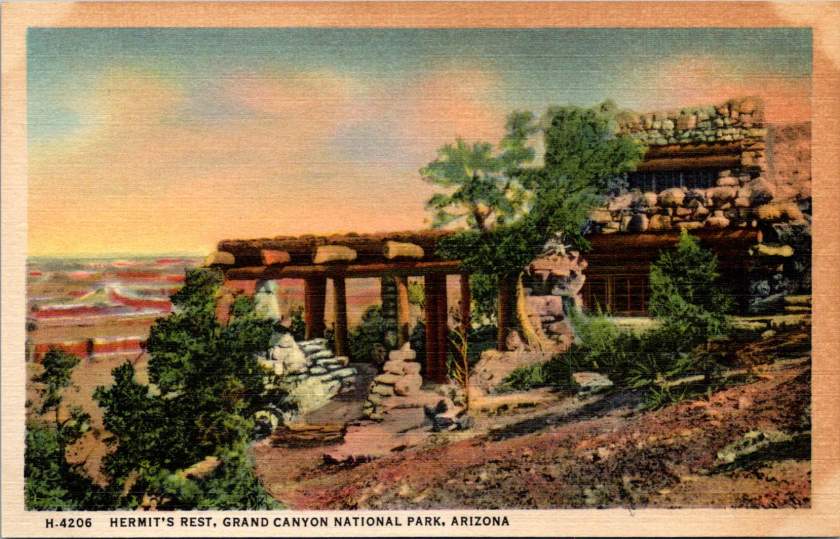

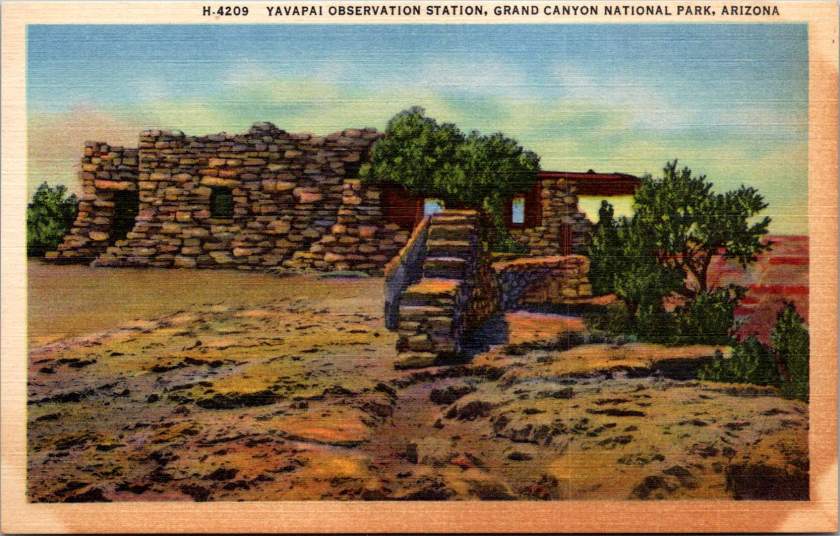

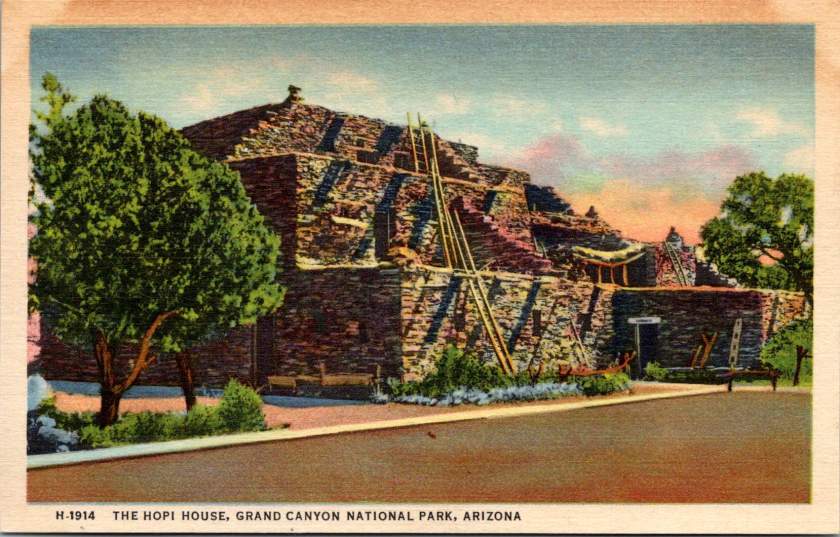

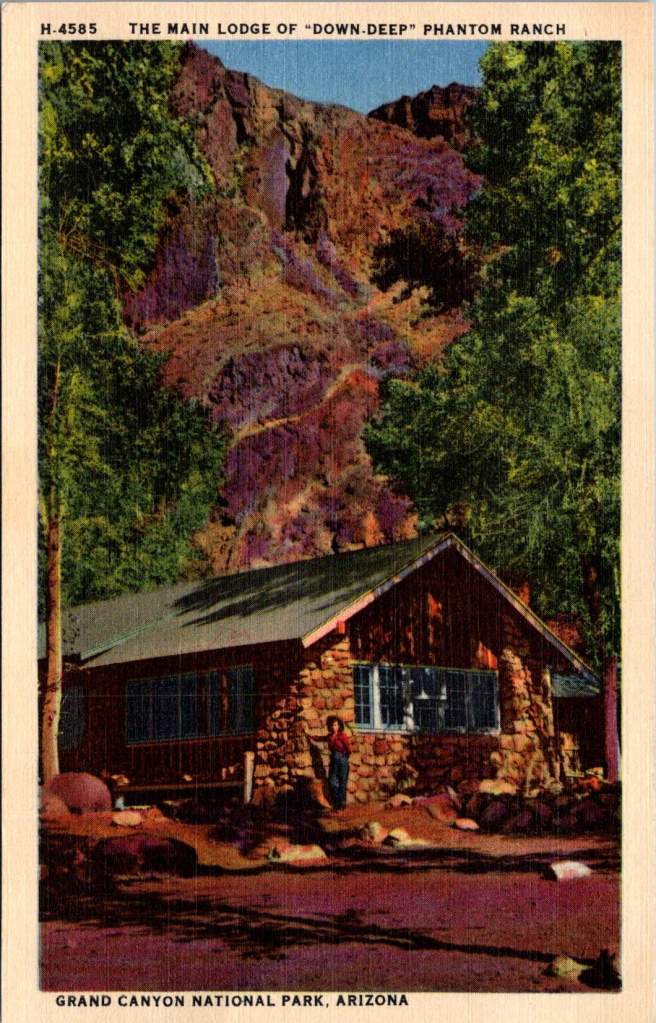

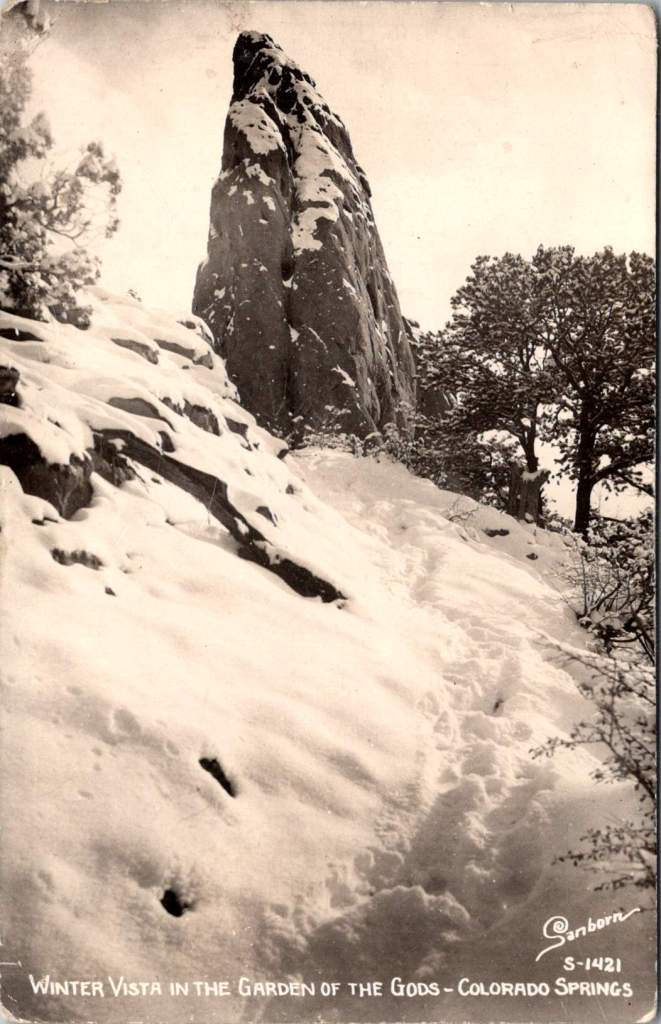

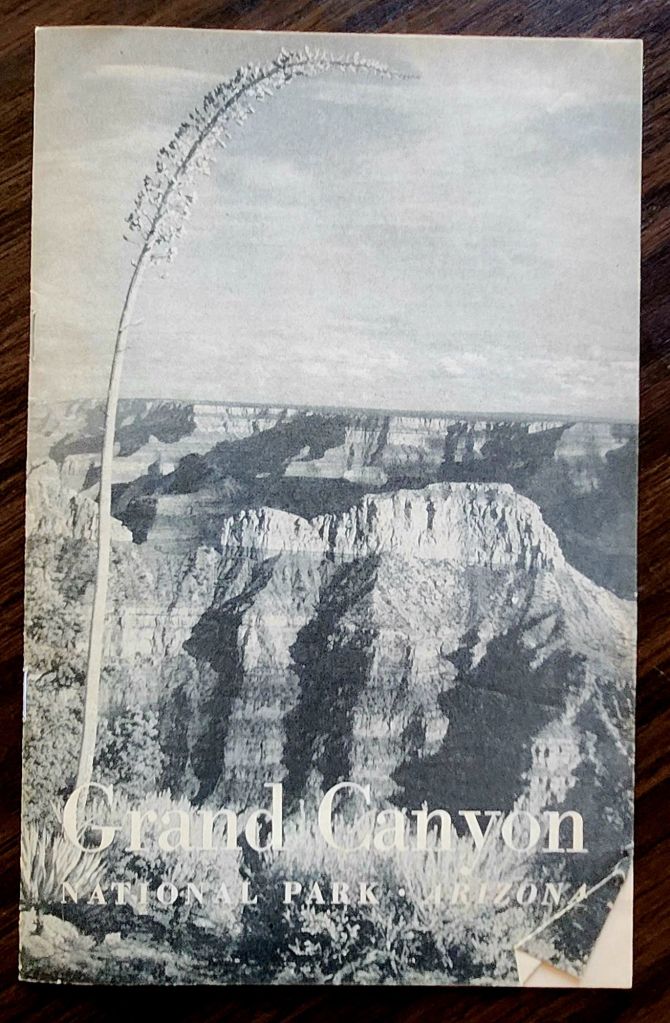

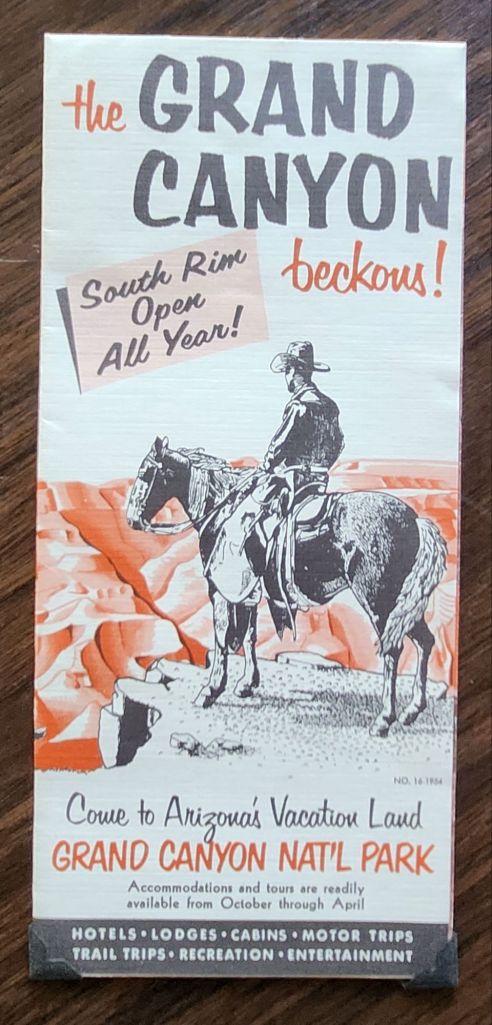

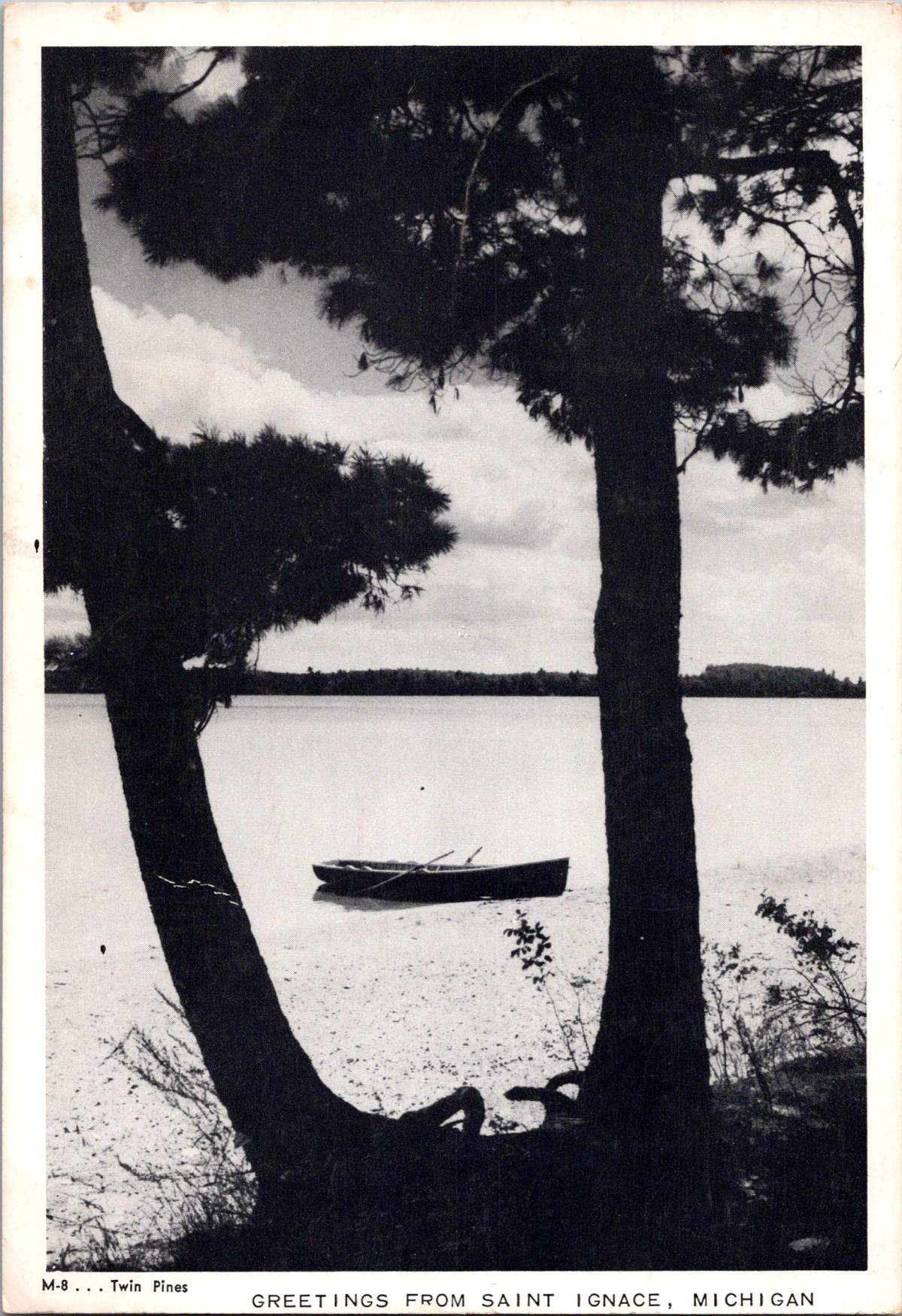

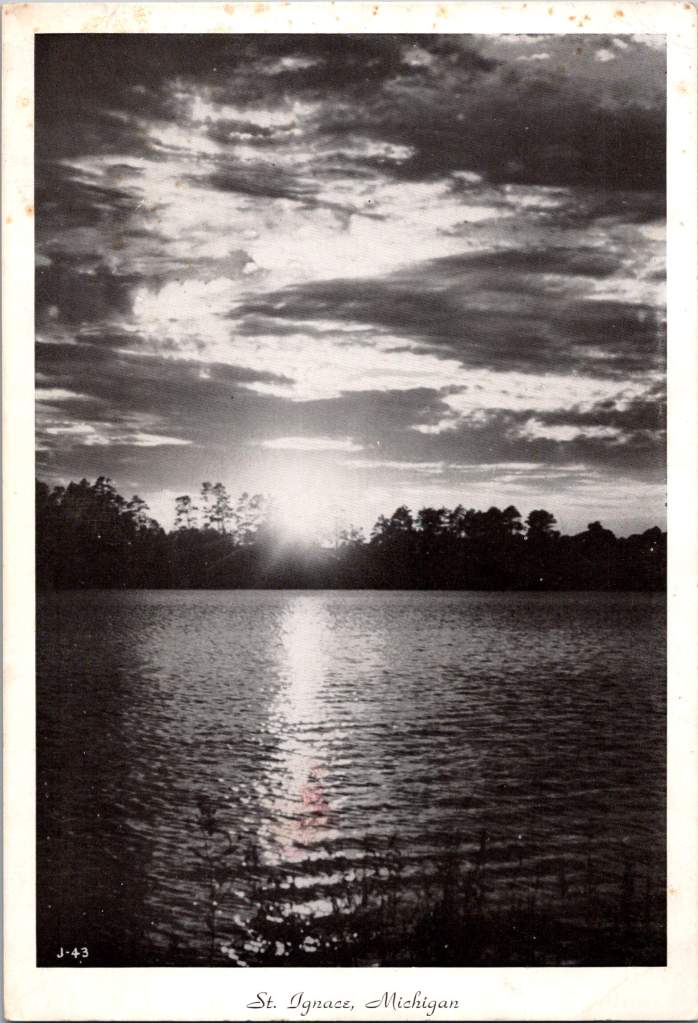

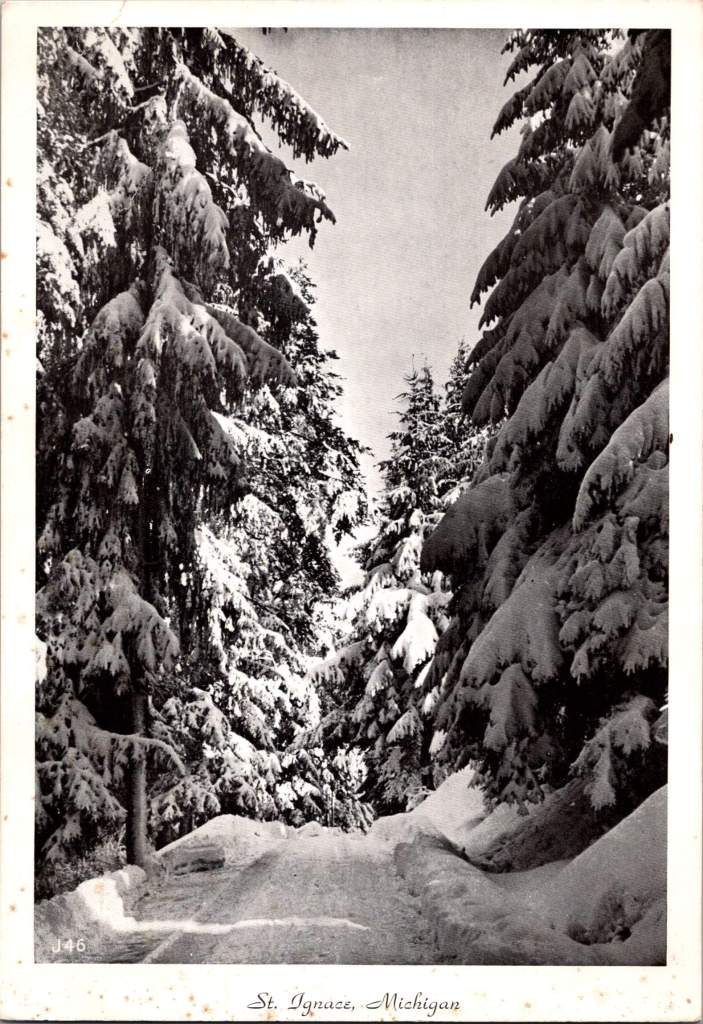

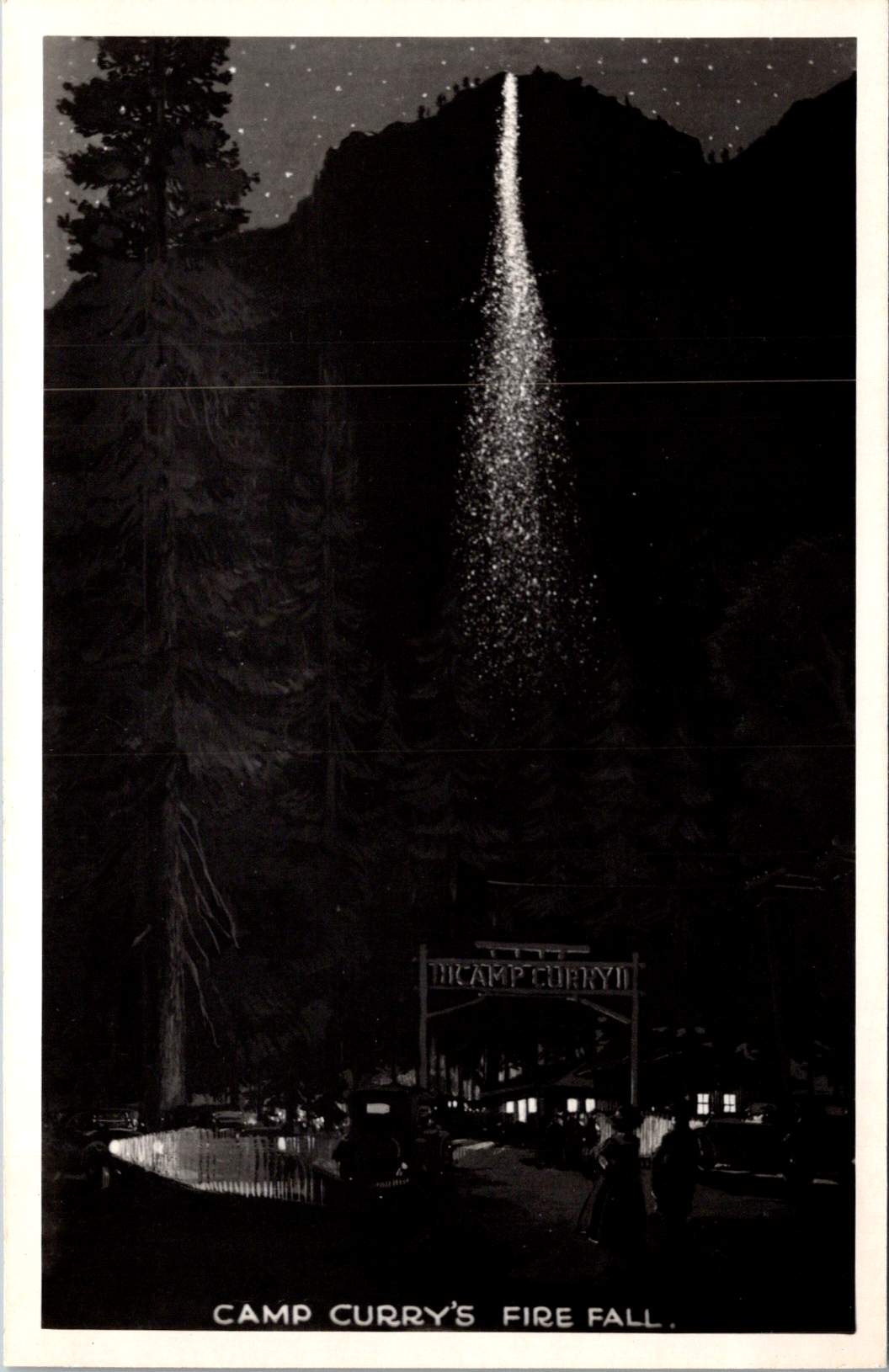

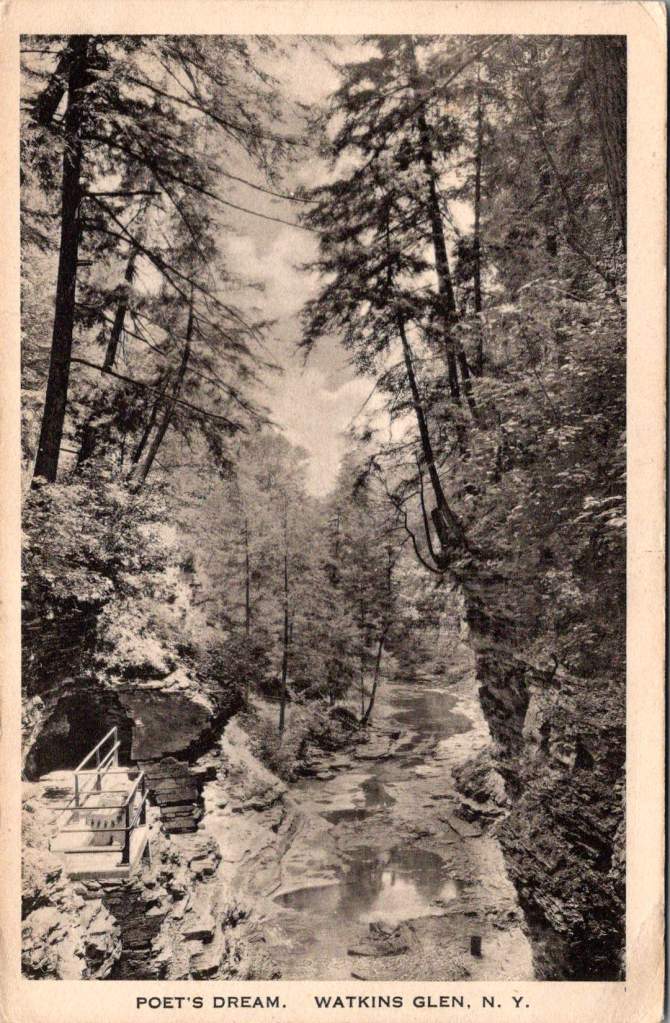

The ephemera spread across my desk capture America’s parks in saturated colors and earnest prose. Welcome to Yosemite and Camp Curry! The hope is that some special part of life is revealed.

These mass-produced mementos tell a story of democratic access to wilderness, of a shared heritage preserved through an unprecedented system of public lands. But they also hint at something deeper – our innate recognition that we need these spaces not just for recreation, but for restoration.

The same wisdom that guided Eleanor Roosevelt to seek solitude among the trees has been confirmed by modern science: nature calms us at a biological level.

Science of Serenity

When we step into a forest, our bodies respond immediately. Cortisol levels drop. Blood pressure decreases. Our parasympathetic nervous system – responsible for rest and recovery – becomes more active.

Even our visual processing changes: natural fractal patterns, like those found in tree branches and leaf veins, require less cognitive effort to process than the sharp angles and straight lines of human-made environments.

Trees release compounds called phytoncides that, when inhaled, enhance immune function and reduce stress hormones. Natural sounds – running water, rustling leaves, bird songs – engage our attention in a way that promotes neural restoration rather than fatigue.

Physiologically, exposure to diverse natural environments even affects our microbiome – the community of microorganisms living in and on our bodies. This microscopic ecosystem influences everything from mood regulation to stress response through the gut-brain axis. In a very literal sense, communion with nature changes who we are.

Preserving Peace

The story of how Americans came to preserve our wild spaces is, in many ways, a story about seeking peace – both personal and collective. The movement gained momentum after the Civil War, as a wounded nation looked westward not just for expansion, but for healing.

Frederick Law Olmsted, who fought depression throughout his life, designed public parks as democratic spaces where people of all classes could find restoration. His work on New York’s Central Park and other urban green spaces was guided by his belief that nature’s tranquility could help ease social tensions and promote civic harmony.

John Muir found his own peace in the Sierra Nevada after wandering the war-torn South as a young man. His passionate advocacy helped establish Yosemite National Park and inspired generations of conservationists.

But it was President Theodore Roosevelt, another seeker of nature’s consolation, who would transform individual inspiration into national policy. Roosevelt’s experience finding solace in the Dakota Territory after the deaths of his wife and mother shaped his approach to conservation. He understood viscerally that wilderness could heal, that it offered something essential to the human spirit.

During his presidency, he protected approximately 230 million acres of public land, establishing 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reservations, four national game preserves, five national parks, and 18 national monuments.

Women in the Woods

While Roosevelt’s dramatic expansion of public lands is well known, the role of women in American conservation deserves greater recognition.

Susan Fenimore Cooper, a student of her famous father, published Rural Hours in 1850 – a detailed natural history that influenced both Thoreau and the early conservation movement. Her careful observations helped Americans see local landscapes as worthy of preservation.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas fought to protect the Florida Everglades when most saw it as a worthless swamp. Her 1947 book The Everglades: River of Grass transformed public understanding of wetland ecosystems. She found that regular communion with nature sustained her through decades of advocacy work.

These leaders shared a practical approach to conservation, focusing on specific, achievable goals while maintaining remarkable equanimity in the face of opposition. Their work suggests that protecting nature and being protected by it can form a reciprocal relationship – the more we preserve wild spaces, the more they preserve something essential in us.

Dark Places

The path to peace often leads through our own shadows. While Americans preserve scenes of spectacular beauty, the relationship between nature and human resilience has been proven most powerfully in places of confinement and struggle. These dark places – prisons, exile, places of oppression – have paradoxically served as crucibles for some of humanity’s deepest insights about peace and connection to nature.

Nelson Mandela’s garden on Robben Island stands as a profound example. In the harsh environment of a maximum security prison, Mandela and his fellow prisoners created a garden in the courtyard where they crushed limestone. In his autobiography, he wrote: “A garden was one of the few things in prison that one could control. To plant a seed, watch it grow, to tend it and then harvest it, offered a simple but enduring satisfaction. The sense of being the custodian of this small patch of earth offered a small taste of freedom.”

This echoes the experience of Albie Sachs, who after surviving an assassination attempt that took his arm and the sight in one eye, found healing partly through his connection to the natural world. During his recovery, watching the ocean’s rhythms helped him develop the concept of his later book – Soft Vengeance – achieving justice through law rather than violence.

Martin Luther King Jr. often drew on natural imagery to maintain his equilibrium and express his vision during frequent detainment. From the Birmingham Jail, he wrote of the majestic heights of justice and used metaphors of storms and seasons to describe the civil rights struggle. His deep understanding of peace was shaped not just by moments of tranquility in nature, but by finding inner calm in places of confinement.

The Dalai Lama often speaks of how the Himalayas’ steady presence influenced Tibetan approaches to maintaining calm, even through decades of exile.

These experiences remind us that while we focus on America’s preserved wilderness spaces, the human need for connection to nature is universal. Peace is an American pursuit and a global birthright. When we protect natural spaces, we’re participating in something that transcends national boundaries – the preservation of humanity’s common sanctuary.

Paths to Peace

The leaders who shaped American conservation found different routes to and through nature. John Muir sought transcendent experiences, climbing trees in storms and walking thousands of miles in solitude. Gifford Pinchot, first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, took a more systematic approach, seeking balance between preservation and sustainable use. Rachel Carson combined meticulous scientific observation with poetic sensitivity to nature’s rhythms.

Their examples suggest there is no right way to find peace in nature. Some need solitude and silence. Others seek the raw tests of strengths and capacity, and find restoration in active engagement with the natural world. Some seek dramatic landscapes to ponder in awe, others find sufficient wonder in a city park or backyard garden.

Wild Wisdom

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his essay on Nature, “…in the woods, we return to reason and faith.” His words point to something profound about nature’s effect on human consciousness – how it seems to restore us not just to calm, but to our truest selves.

Modern research into nature’s calming effects – the lowered cortisol, the enhanced immune function, the restored attention – helps explain the mechanisms behind what people have long intuited. For those who find great equanimity through connection with nature, there also seems to be an innate genius in each of us that emerges more fully in wild spaces.

We might experience this as artistic, spiritual, or intellectual – and perhaps even more fundamental – a capacity for presence, for wonder, for sensing our connection to something larger than ourselves. It’s what Eleanor Roosevelt accessed on her morning walks, what John Muir celebrated in his rhapsodic nature writing, what Jane Goodall tapped into during her patient observations of primates in Gombe.

The preservation of wild spaces represents more than conservation of natural resources or recreational opportunities. It preserves access to this deeper part of ourselves – the part that knows how to find peace, that remembers how to wonder, that recognizes our belonging in the larger community of life.

These vintage postcards capture more than just scenic views. They record moments when people felt called to share their experience of wonder, to say to friends and family that the experience mattered. The fact that we’ve preserved and share these places, despite constant pressure to exploit them, suggests we recognize they offer something essential to human flourishing.

Why the woods? Because something in us comes alive there. Because in preserving wild spaces, we preserve the possibility of encountering our own wild wisdom, and these revelations are too precious not to protect for future generations.

Each time we step into nature – whether it’s a national park or a neighborhood green space – we participate in this legacy of preservation. We join a long line of people who recognized that human flourishing depends on maintaining connection to places where we might find peace and that help us face whatever challenges await when we return.