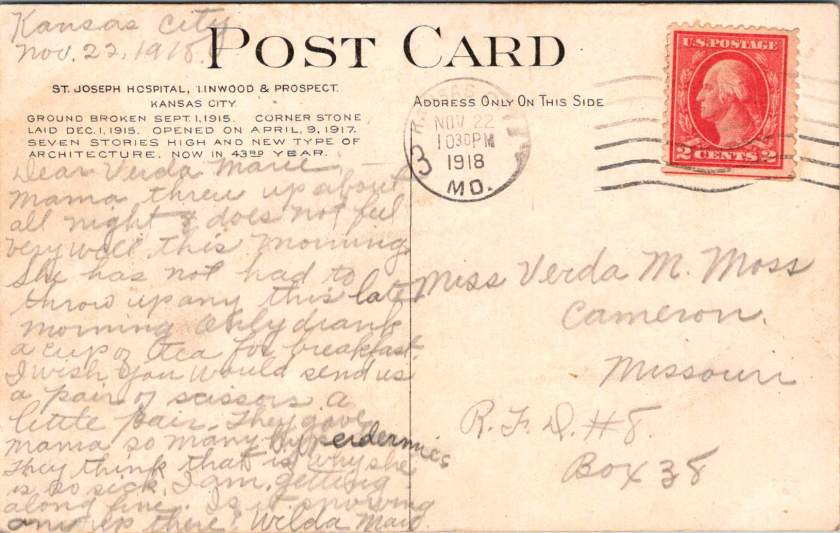

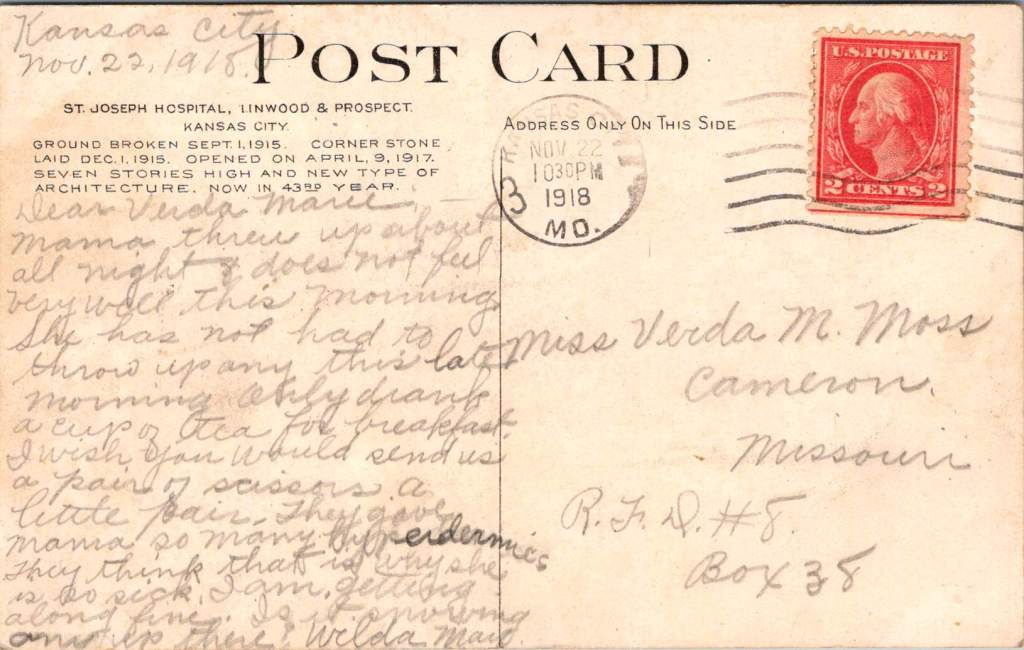

A postcard trembles in worried hands. On the front, St Joseph Hospital, Linwood & Prospect Streets in Kansas City, Missouri. Victorian landscaping, tree-shaded boulevards, a large, new hospital. It is a world of progress and prosperity frozen in glossy perfection.

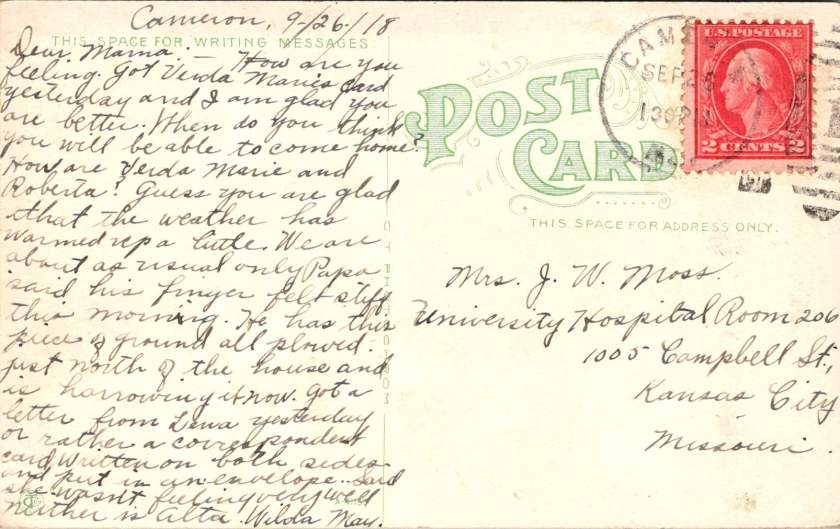

Turn the card over. Faded ink bleeds across cream paper. “Dear Verda Marie, Mama threw up all night and does not feel well this morning… only drank a cup of tea for breakfast.”

Two worlds exist on a single postcard. The front celebrates America’s gleaming cities and grand institutions. The back reveals a family torn apart by pandemic and war, working together and staying in touch every day.

The Spanish flu arrived in Missouri like a thief. It followed railroad lines and river valleys, spreading from military camps across the heartland. By September, Kansas City reported its first cases. By October, the city’s hospitals overflowed with the gravely sick and dying.

Mama Moss checked into University Hospital on Campbell Street, one of several small places on Hospital Hill, where Kansas City built its first medical facility in 1870. Now every building overflowed with sick and strapped families seeking any treatment that promised relief or protection.

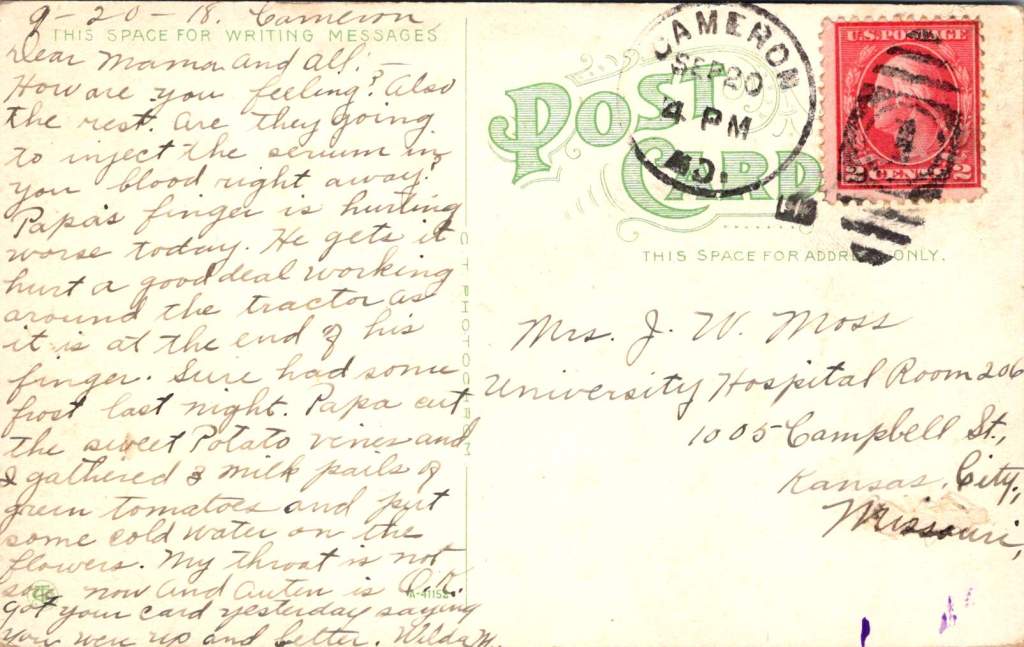

The postcards begin their daily journey between Cameron and Kansas City. Fifty miles of prairie separate farm from hospital, family from mother, routine from crisis. September 20th,Verda Marie writes from Cameron:

Dear Mama, and all. How are you feeling? And the rest. Are they going to inject the serum by your blood right away? Papa’s finger is hurting worse today. He gets it hurt a good deal working around the tractor.

The serum treatments represented medicine’s desperate gamble. Doctors extracted blood from recovered patients, believing their antibodies might save others. Transfusion methods were primitive—donor to patient through crude tubes, with minimal understanding of blood compatibility.

The front of her postcard shows Fourth Street looking west in Cameron—tree-lined and peaceful, houses with wraparound porches and manicured lawns. No hint of pandemic. No suggestion of families split between farm work and hospital vigils.

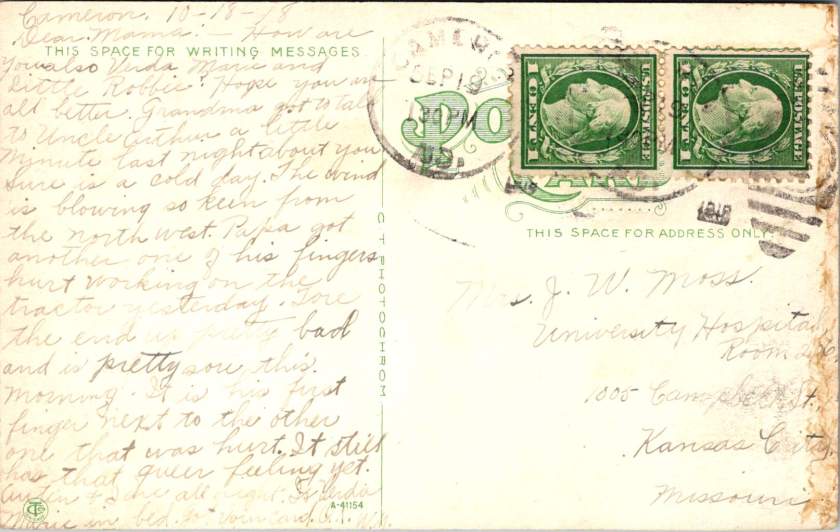

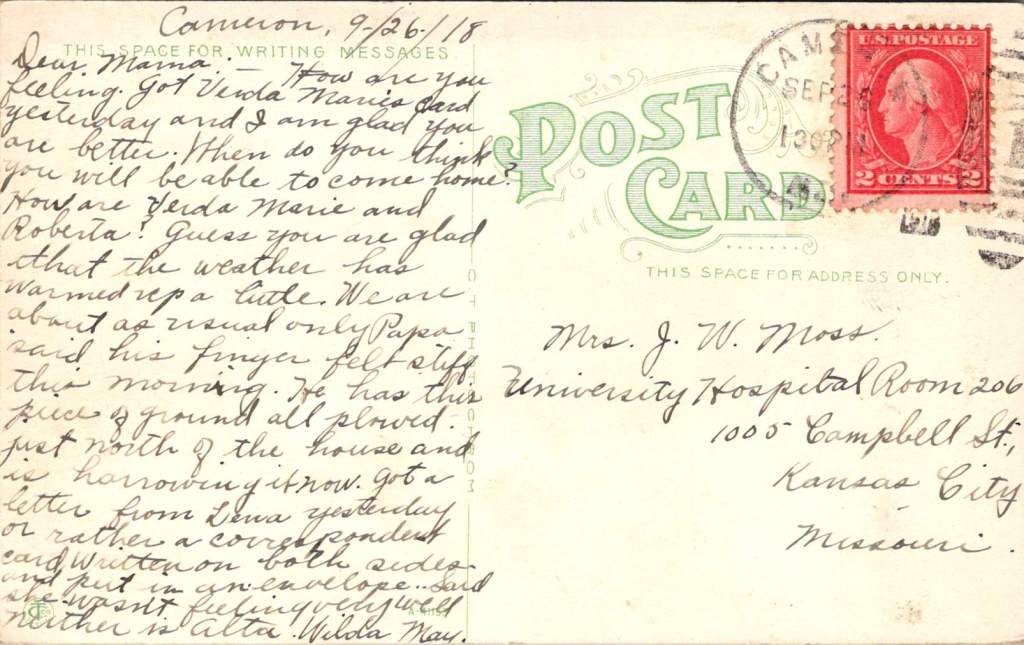

September 26, another postcard from daughter Wilda May in Cameron. Papa keeps working despite his damaged fingers. Farming cannot stop, even during plague, while war production and domestic demands for food are high. Families managed alone while the virus spread through communities like wildfire.

Dear Mama, got Verda Marie’s card yesterday. I am glad you are better. When do you think you will be able to come home? … Papa said his finger felt stiff this morning. He has this piece of ground plowed north of the house and is harrowing it now.

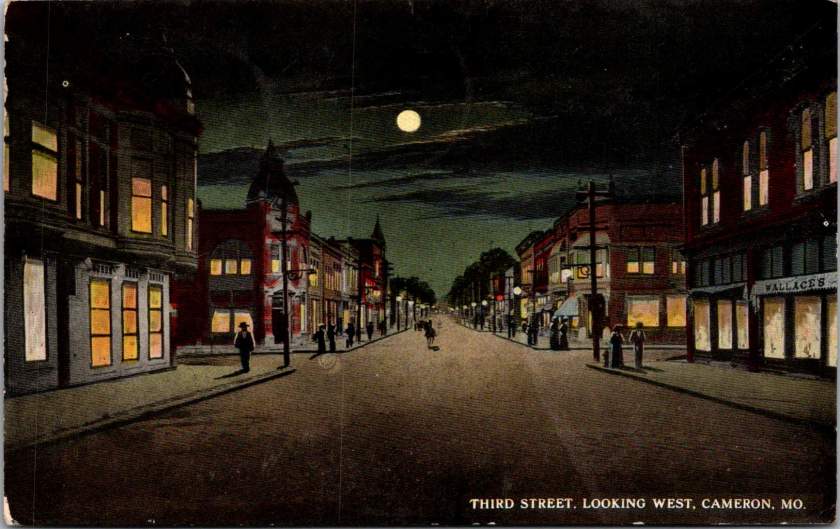

This card displays the Third Street business district looking East. The image suggests normalcy, prosperity, urban activity. The message tells a different story—injury, illness, fragmented family life.

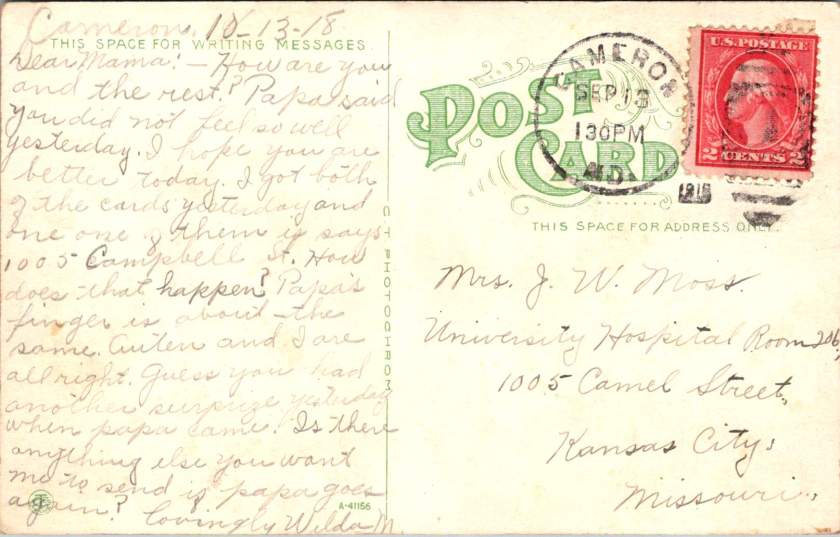

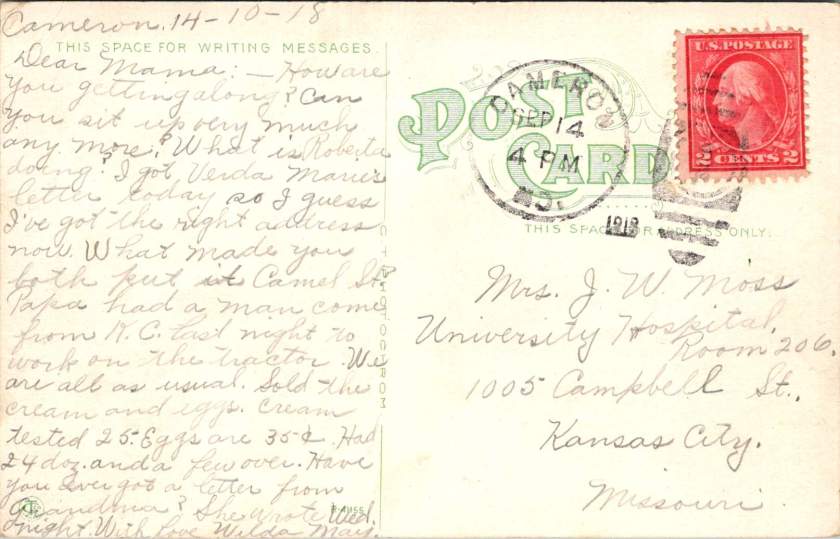

October 14th, from Cameron, Wilda May is writing to check in on Mama, Verda Marie, and little Roberta.

How are you getting along? Can you sit up very much any more? Papa had a man come from K.C. last night to work on the tractor. Sold the cream. Eggs are 35 cents. Had 24 dozen and a few left over.

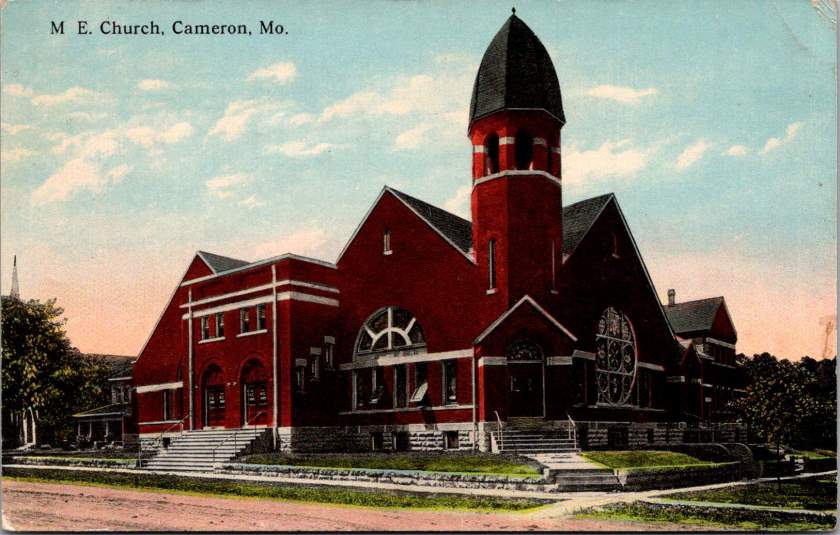

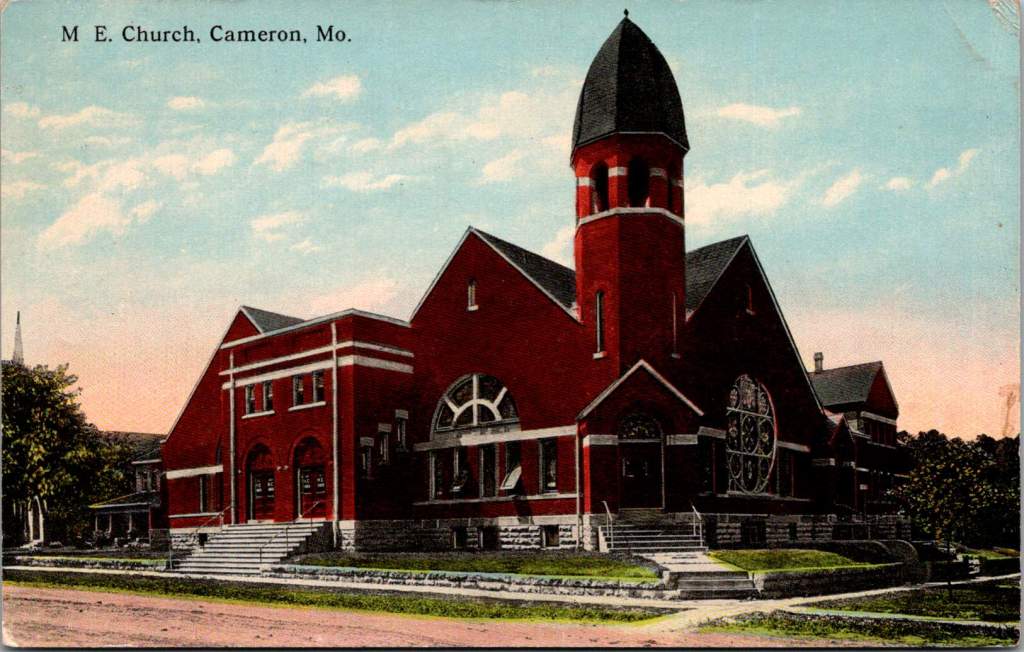

The dramatic red brick architecture of the M.E. Church is featured on the front. The bell tower, archways, and stained glass, no doubt concealing a community in a moment of great challenge.

November arrives with mixed signals. The Great War ends with armistice celebrations flooding city streets. Victory parades march through Kansas City while Hospital Hill counts mounting dead.

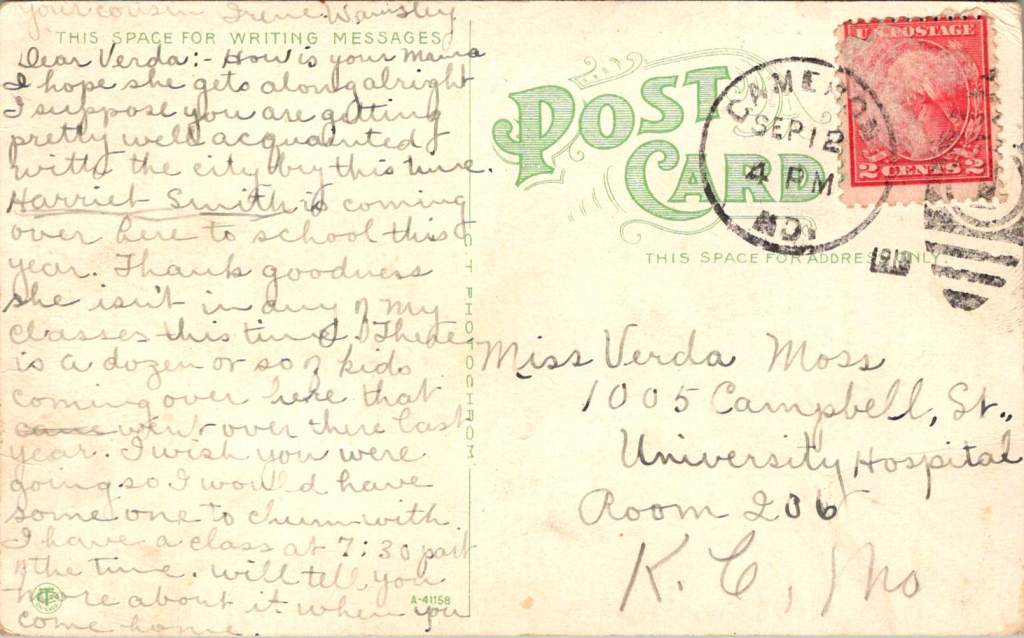

November 22nd, Wilda May is now in Kansas City and Verda Marie is back in Cameron. This is the card with St Joseph Hospital on the front and a report of Mama’s worsening condition on the back. Poignantly, a plea for simple materials.

I wish you would send us a pair of scissors, a little pair. They gave Mama so many hyperdermics (sic). They think that is why she is so sick.

The front shows St. Joseph Hospital—imposing, institutional, representing medical progress. The message reveals the grinding reality inside: nausea, sleepless nights, requests for basic supplies.

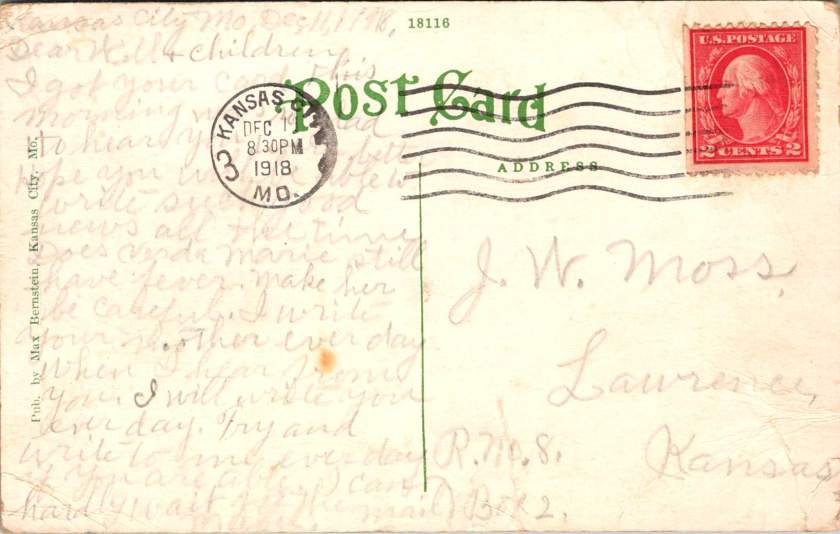

December 11, 1918. The last postcard in this series leaves Kansas City at 8:30 PM. Mabel Moss writes with exhaustion and desperate love.

Does Verda Marie still have a fever? Make her be careful. Write to your mother every day. I will write to you each day, too.

She repeats herself. Write every day. Every day, I will write to you.

These postcards have become more than communication. They serve as proof of life, wellness checks, emotional anchors in a world gone mad. Each delivery confirms another day fought forward, another family member still breathing.

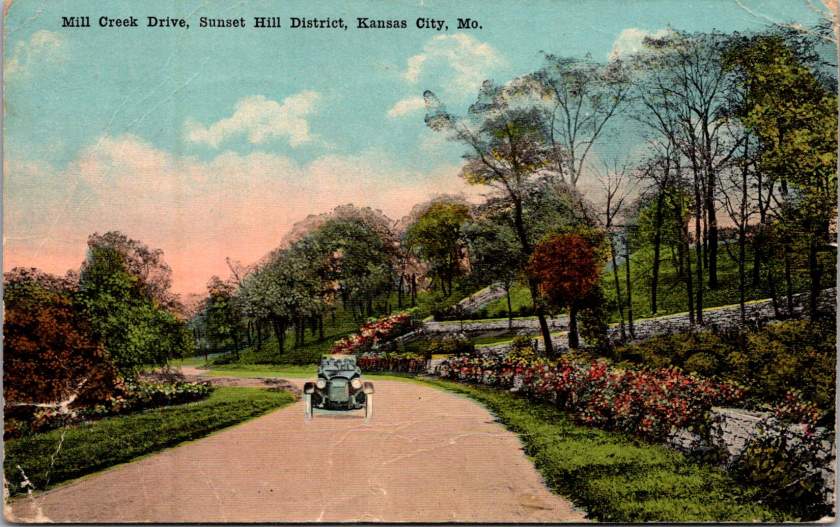

The front of the card features a swank soft top automobile on Mill Creek Drive, in the Sunset Hill district of Kansas City, Missouri. Lush foliage suggests it is a wonderful day to take in the fresh air.

Armistice brought celebration but not peace. Fighting continued in distant lands. The temporary ceasefire required renewal every thirty-six days. Victory was fragile, conditional, threatened by forces beyond control.

Also, influenza had no respect for borders. While diplomats negotiated peace terms, the 1918 pandemic waged its own relentless war. Families learned that health status changes cruelly and without warning. People woke well and died by nightfall.

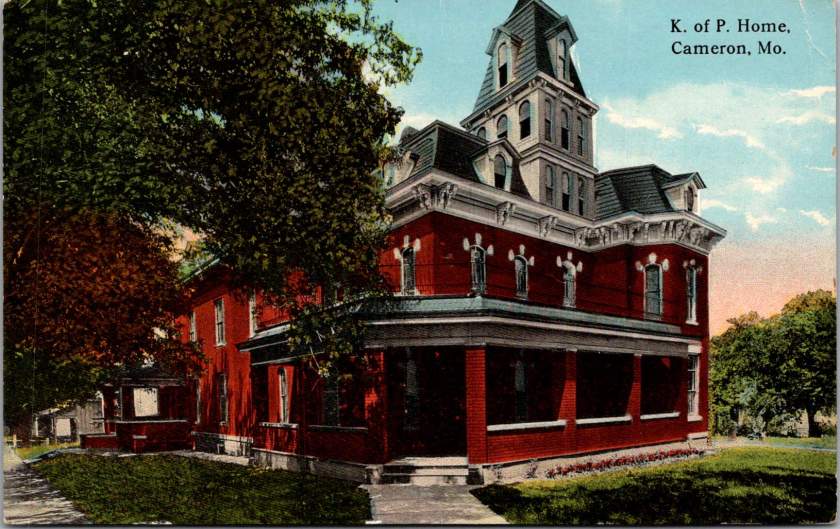

These postcards preserve this tension between public aspiration and private desperation, helping us journey back to history as it happened. The fronts of the postcards celebrate civic pride—hospitals, colleges, tree-lined streets, architectural monuments. Their backs tell different stories. Experimental medical treatments. Daily fears about fever and death. Constant threat of injury from dangerous farm equipment. The grinding reality of families separated by crisis, held together by handwritten words.

This contrast defines the American experience during a period of dual catastrophes. Communities built beautiful institutions while individuals struggled for survival and missed hard earned opportunities. Cities planned grand boulevards while families split between hospital rooms and farm chores. America as it aspired to be, and as it actually existed for the Moss clan.

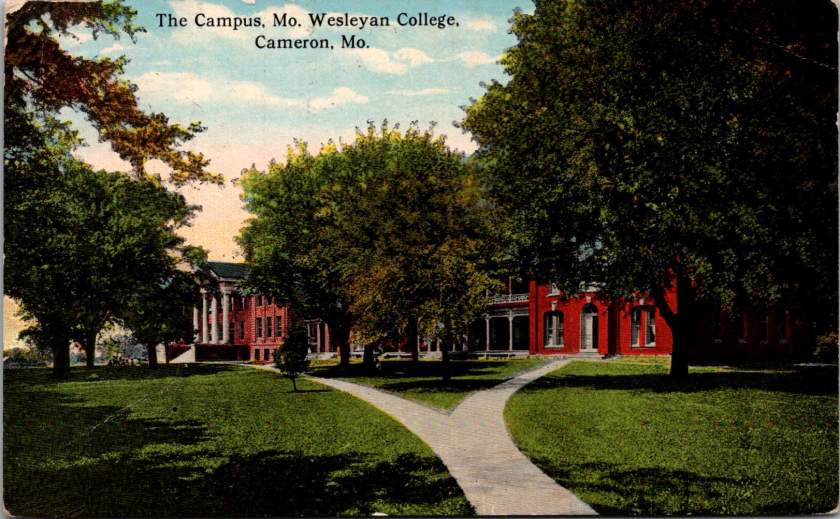

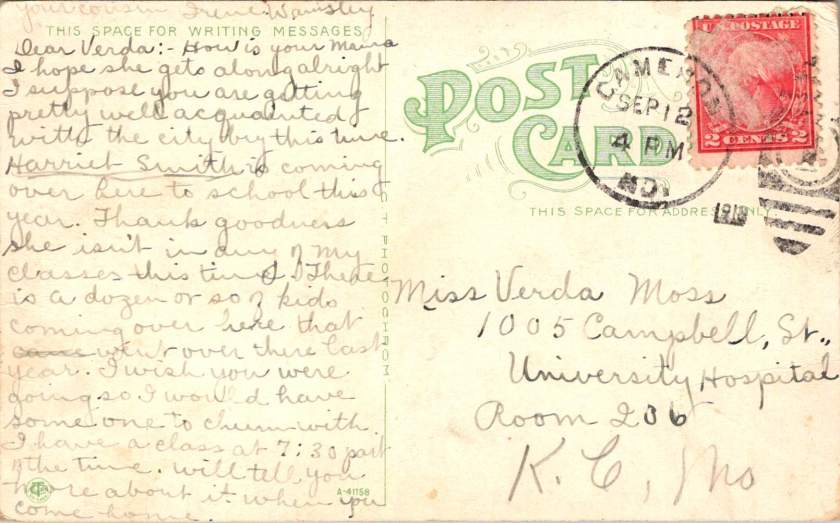

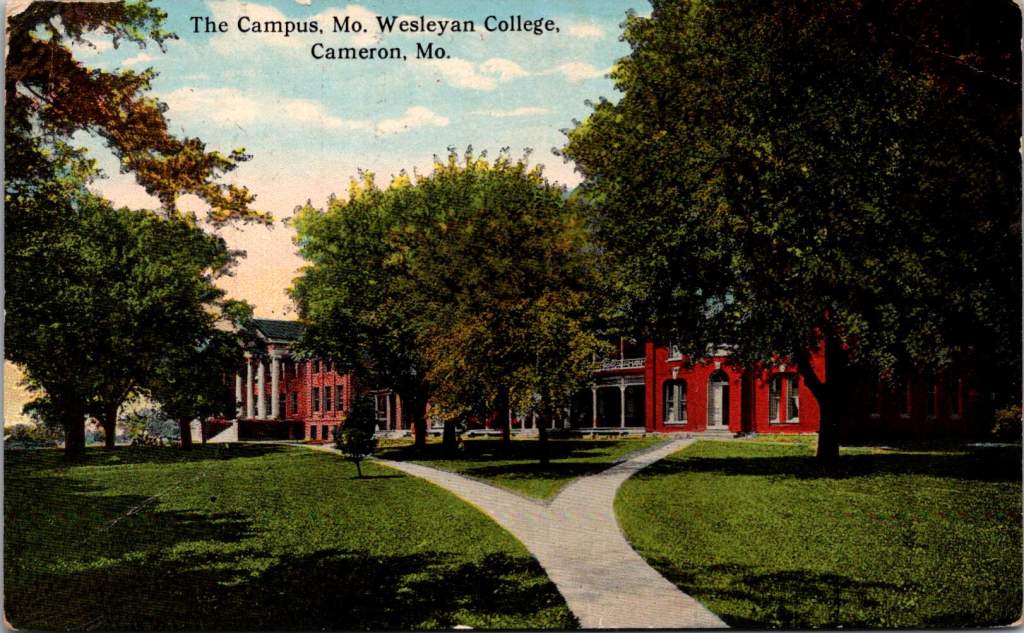

Just as her mother was getting sick, Verda Marie received a cheery postcard from a classmate with some gossip to share.

Harriet Smith is coming over here to school this year. Thank goodness she isn’t in any of my classes … I wish you were going so I would have someone to chum with…

The postcard front featured Missouri Wesleyan College campus—red brick buildings set among autumn trees. The front speaks to knowledge, tradition, the future of young minds. We can read between the lines on the back. Verda Marie would not be in class that semester, sadly.

Like Lazarus rising from his tomb, the world emerged from pandemic death to discover life transformed. The 1920s roared with celebration and renewal, and time went on. Hospital Hill expanded into Kansas City’s premier medical district. The red brick buildings where Mama received her serum treatments evolved into modern towers serving new generations. A century later, technological and medical innovations advance but essential human needs persist, too: connection, communication, proof that loved ones survive another day.

These particular postcards survived in a family archive. Stories of courage, love, determination tucked away to find a century later. Each card represents a day won against the odds, a family bond that transcended distance and disease.

The Moss family’s story continues in everyone separated by illness, every community battling invisible enemies, every healthcare worker risking their life to save others. The beautiful facades combined with harrowing messages remind us that hope and suffering coexist, flipped back and forth in our hands, repeated in every generation.