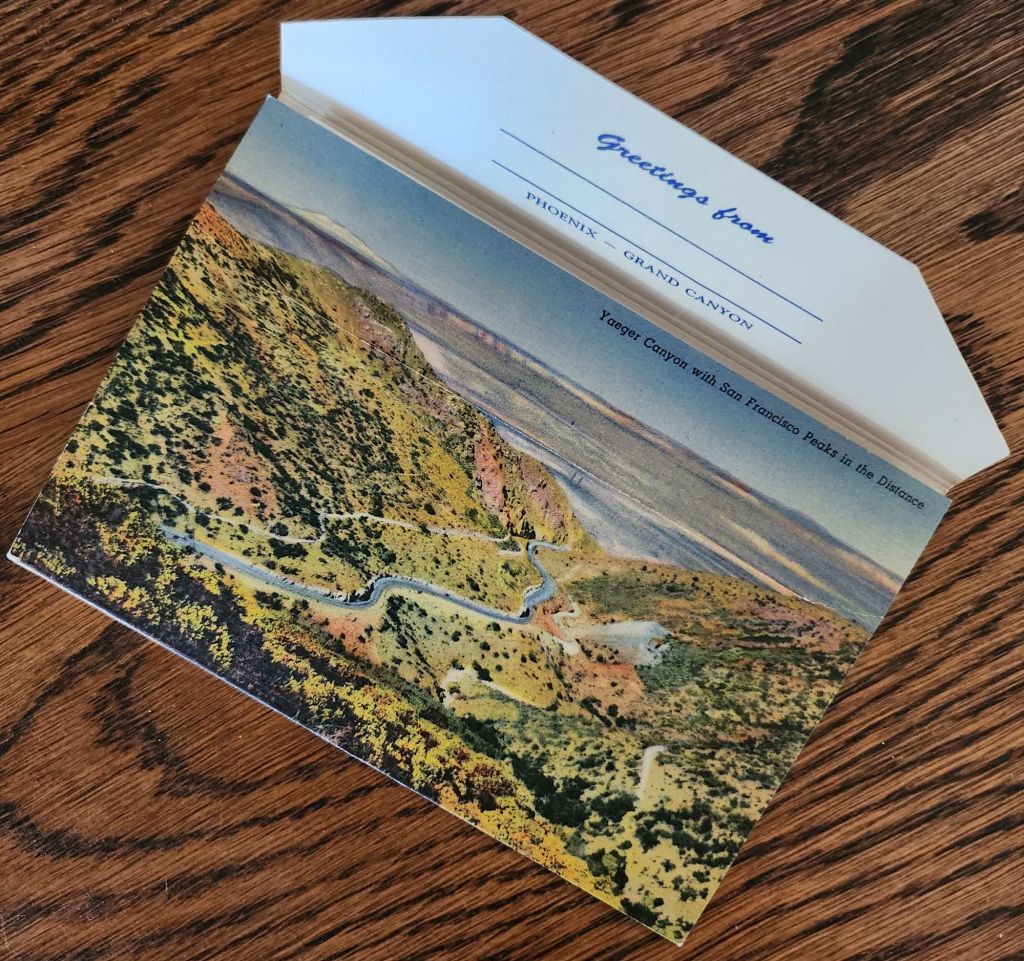

Arizona’s Verde Valley has inspired generations. Journey through this dramatic landscape where red cliffs greet green river valleys, and where an old mining railway now carries visitors through one of the Southwest’s most stunning canyons.

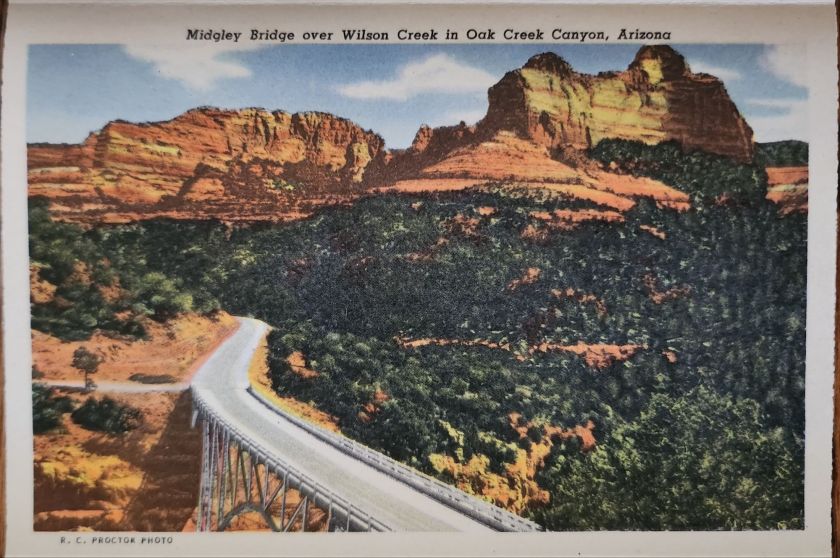

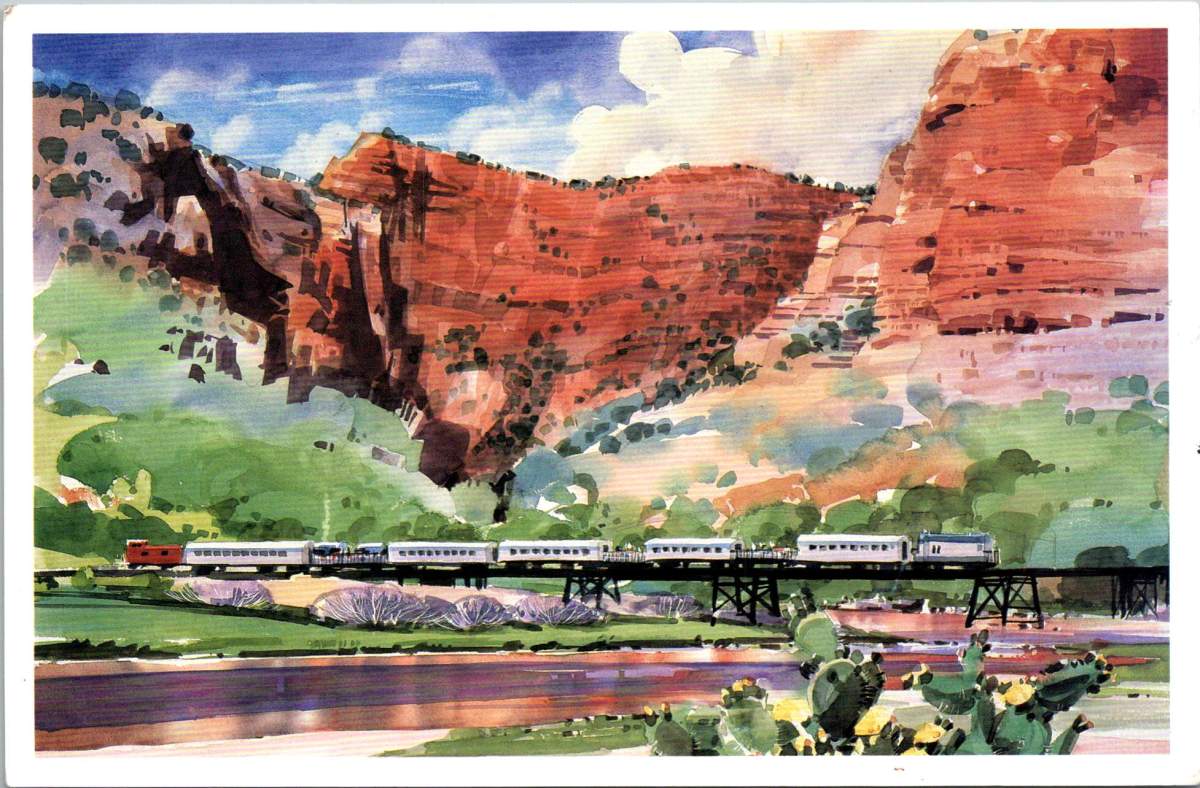

A striking watercolor dominates the front of a vintage postcard. The scene captures the essence of Arizona’s high desert: massive red rock canyon walls rise dramatically against a blue sky dotted with billowing clouds, while a silver passenger train glides across a trestle bridge below. The unknown artist’s watercolor brushwork renders the desert vegetation in soft greens, with prickly pear cactus dotting the foreground. The painting masterfully conveys both the monumental scale of the landscape and the delicate play of light across the rocky surfaces.

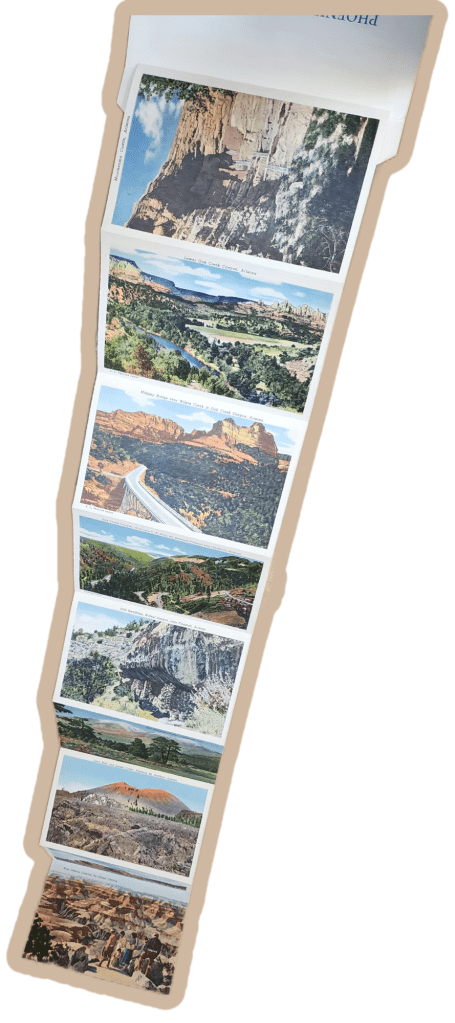

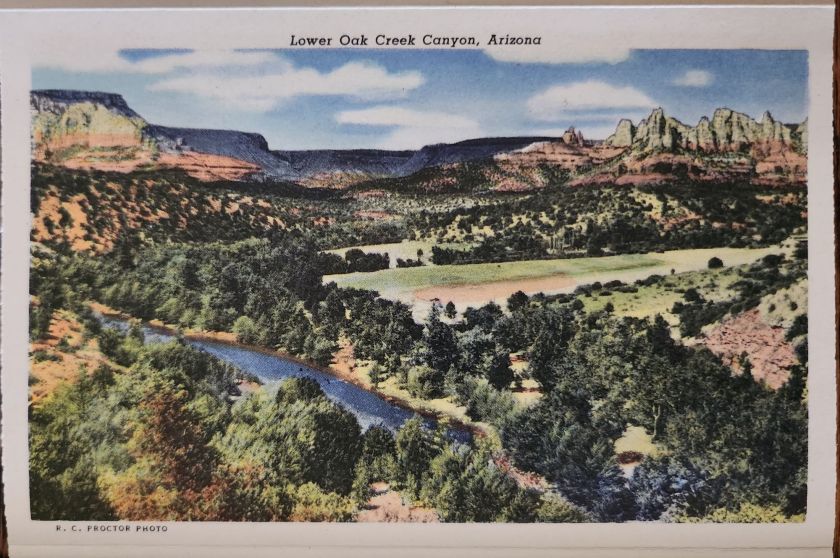

When the Verde Canyon Railroad winds through the high desert country of central Arizona, it follows ancient pathways. The Verde River carved this dramatic landscape over millennia, creating a riparian corridor that has attracted humans for thousands of years. Today’s passengers on the scenic railway see much the same view as the Sinagua people who built cliff dwellings here between 600 and 1400 CE, though the comfortable rail cars are a far cry from the precarious edges those early inhabitants deftly defied.

The river remains one of Arizona’s few perennial waterways, sustaining a complex ecosystem where desert meets riverbank. Towering cottonwoods and velvet ash trees create a canopy over the water, while sycamores and willows cluster along the banks. Native grape vines twist through the understory, and prickly pear cactus dot the rising canyon walls. This environment supports a rich variety of wildlife, from yellow-billed cuckoos and great blue herons to river otters and mule deer. Native fish species like the razorback sucker still navigate the waters their ancestors swam for millennia.

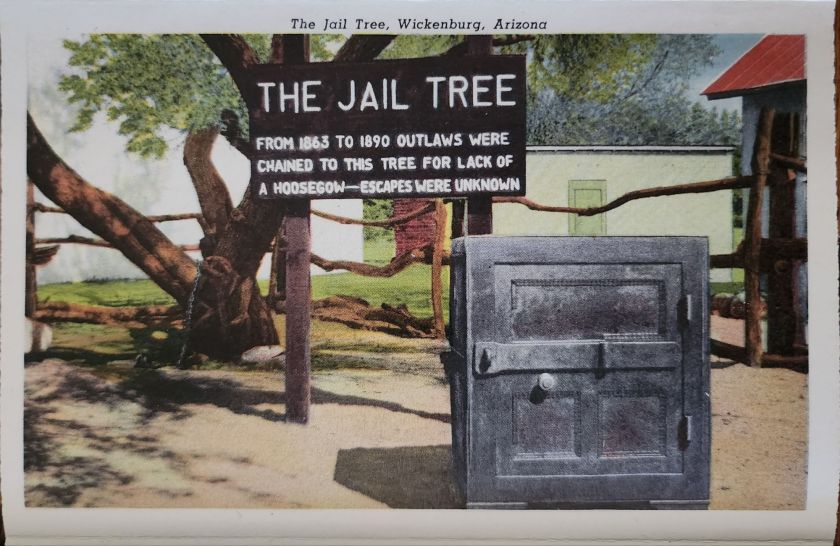

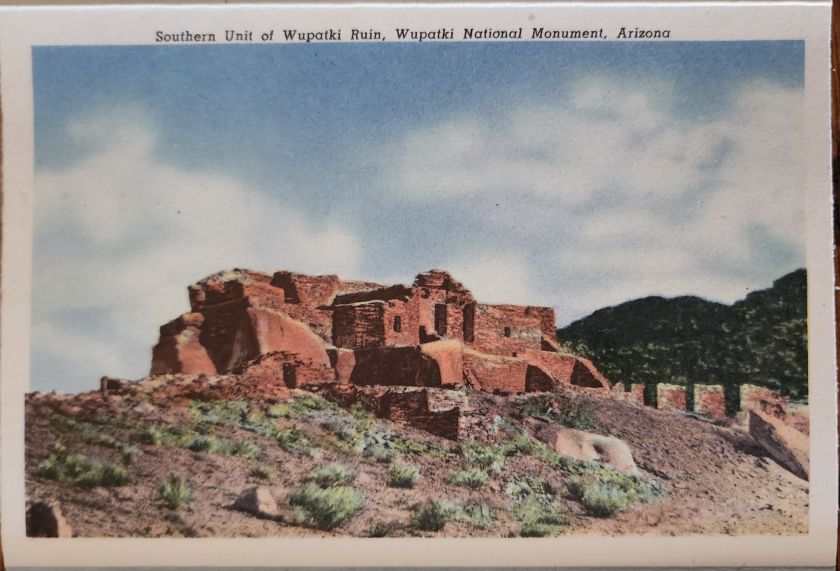

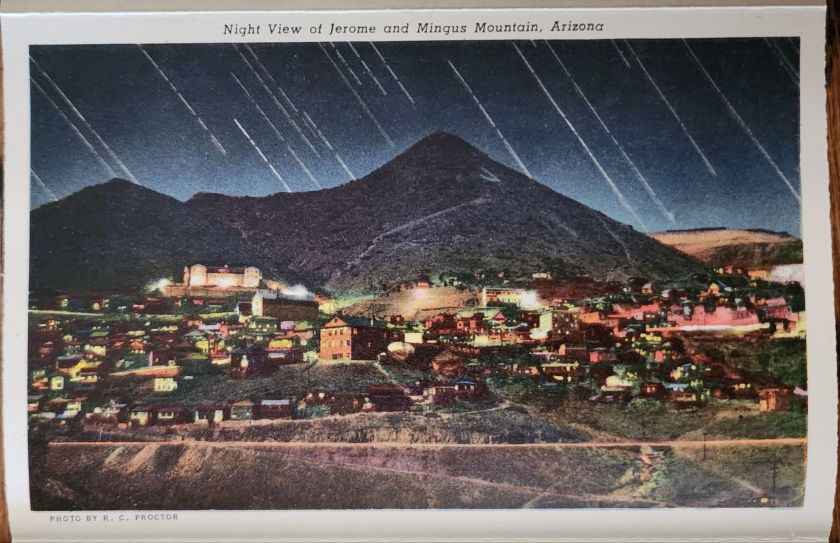

The human history of the valley reflects waves of settlement and industry. After the Sinagua, Yavapai and Apache peoples made their homes here. Spanish explorers gave the river its name – “verde” meaning green – marking the stark contrast between the river corridor and the surrounding desert. The late 1800s brought miners seeking copper, gold, and silver, transforming places like Jerome into boom towns. The railroad itself was built in 1912 to service the United Verde Copper Company’s mining operations, an engineering feat that mirrors our ancient ancestors.

Notable Arizona artists have interpreted this landscape. Ed Mell’s geometric, modernist approach emphasizes the monumental character of the canyon walls. Early pioneer Kate Cory combined artistic and ethnographic interests, documenting both landscape and culture during her years living among the Hopi. Merrill Mahaffey mastered the challenging medium of watercolor to capture the desert’s subtle light and atmosphere, teaching and inspiring so many along the way.

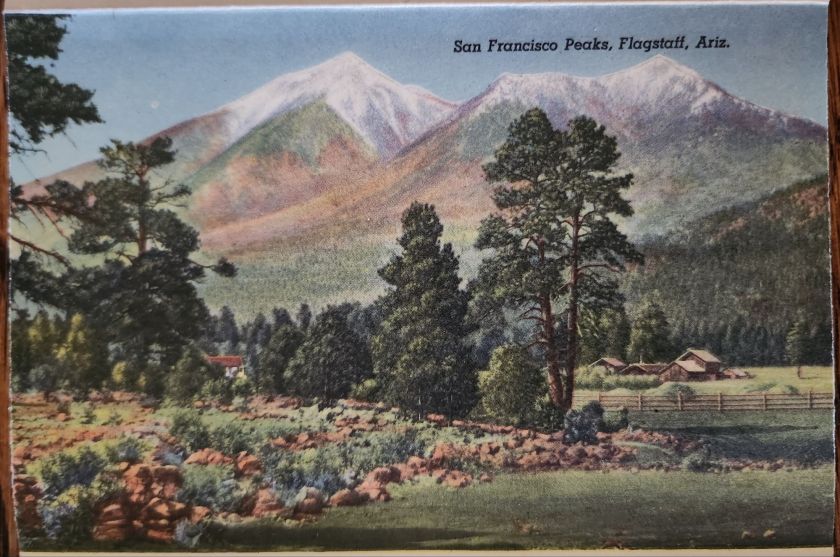

The artistic legacy of the region is inextricably linked to its unique quality of light. The clear, dry air creates what painters describe as crystalline clarity, especially during the “golden hours” of early morning and late afternoon. Artists employ various techniques to capture these effects: watercolorists leave areas of white paper untouched to suggest intense sunlight on rock faces, while building up transparent layers to show subtle color variations in shadowed canyon walls. The phrase ‘purple mountain majesties’ from Katharine Lee Bates’s “America the Beautiful” finds visual truth here, where the red rocks shift to deep purple at dawn and dusk, challenging artists to capture these dramatic transformations.

These artistic traditions remain vibrant today through institutions like the Sedona Arts Center, which hosts workshops, exhibitions, and the annual Sedona Plein Air Festival. These events draw artists from around the country to paint the red rock landscapes, continuing a legacy of artistic response to this unique environment.

The Verde Canyon Railroad itself represents a remarkable transformation from industrial resource to cultural attraction. When mining operations declined in the 1950s, the railroad continued operating for freight until the late 1980s. Its reinvention as a scenic railway in 1990 preserved both the industrial heritage and access to the canyon’s natural beauty, offering new generations a chance to experience this remarkable landscape where nature, history, and art converge.

In recent decades, the Verde Valley has emerged as a significant wine and food-producing region, adding another layer to its cultural landscape. The same mineral-rich soil that once yielded copper now nurtures vineyards, while ancient irrigation techniques inform modern water management practices. Local wineries have revived the area’s agricultural traditions, some of which reflect Spanish and Mexican heritage. The region’s restaurants increasingly reflect Native American heritage, too, combining indigenous ingredients with contemporary techniques. Native foods like prickly pear, mesquite, and local herbs appear on menus alongside wines produced from vineyards visible from the train’s windows.

Tourism in Arizona has evolved beyond simple sightseeing to embrace the complex tapestry of the region’s heritage. Visitors to the Verde Valley today might start their morning at an art gallery in Jerome, taste wines produced from hillside vineyards at lunch, and end their day watching the sunset paint the canyon walls from a vintage train car. This integration of historical preservation, artistic tradition, and culinary innovation exemplifies how the creative spirit that first drew people to these dramatic landscapes continues to evolve. The Verde Valley is home to each generation, who find new ways to interpret and celebrate the enduring connections between people and place.