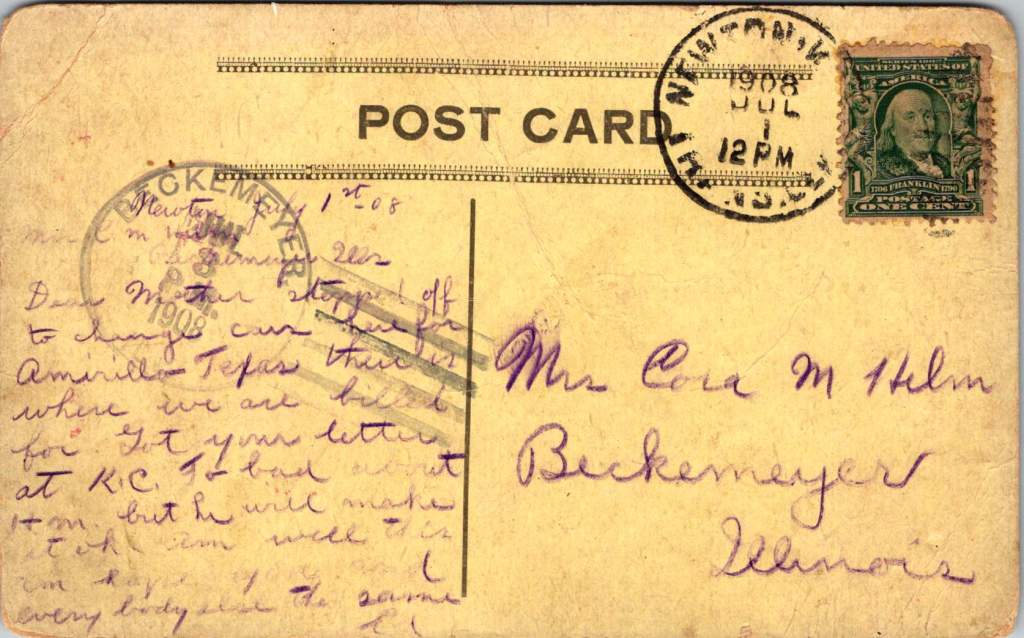

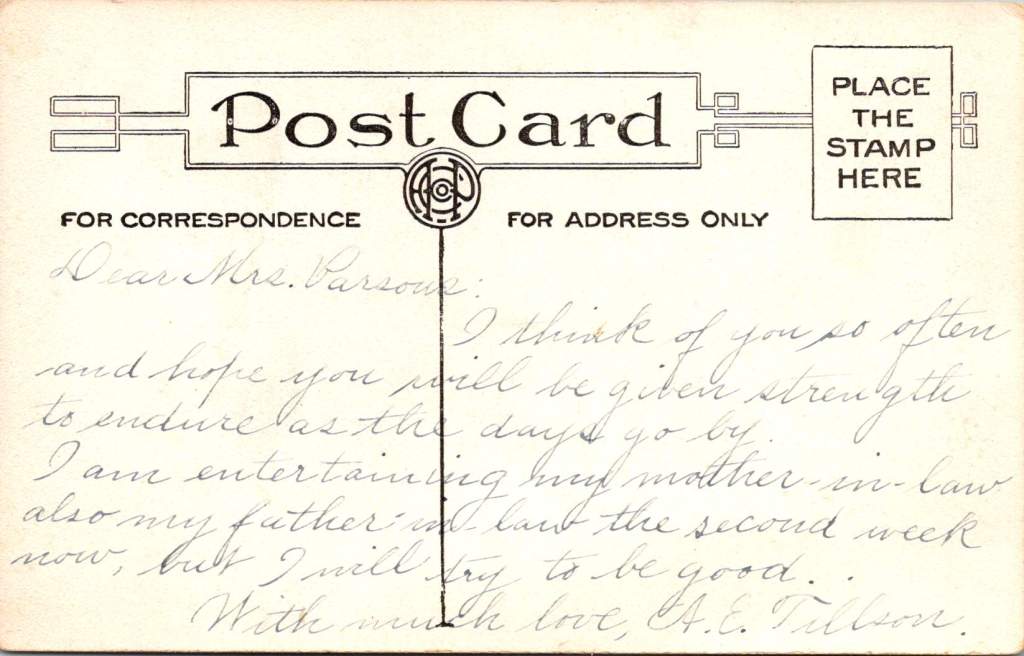

A collection of real photo postcards from this period captures these moments of crisis. One image shows the mill with its flooded surroundings, another the threatened railroad bridge. These weren’t just documentary photographs – they were messages sent between family members grappling with decisions about land and livelihood in the flood’s aftermath.

The Republican River, which meanders through Republic County past the iconic Table Rock formation, swelled beyond its banks, swallowing farmland, threatening towns, and severing the rail lines that served as lifelines for agricultural communities.

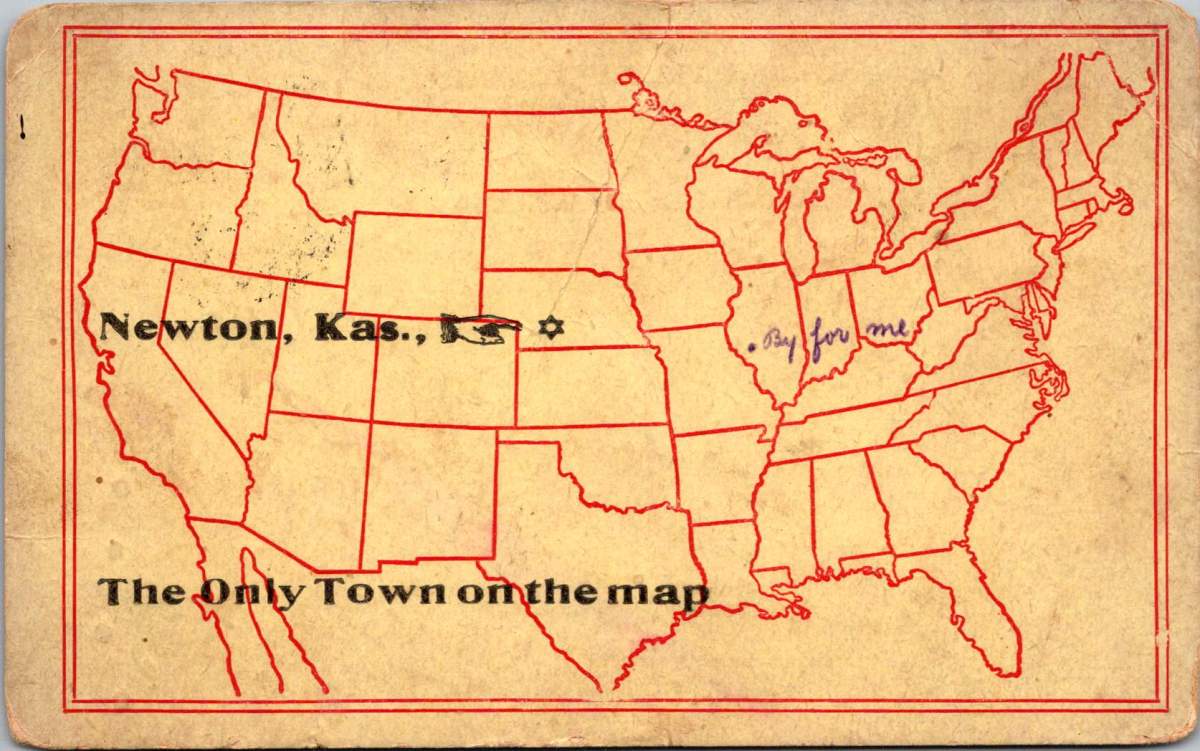

Concordia, the largest town along this stretch of the Republican River, watched as the waters rose. The town of 4,500 residents had built itself on agricultural promise, its grain elevators standing sentinel along the railroad tracks, its mill processing the bounty of surrounding farms. But the 1908 flood challenged this careful progress. Water lapped at the foundations of the mill, its twin smokestacks rising above the flood.

Railroad bridges proved vulnerable to the 1908 flood, too. The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad, which had helped birth towns like Concordia and Republic City, found its tracks suspended over angry waters. Train service halted, leaving farmers isolated with their crops rotting and fields under water. The flood arrived at a particularly cruel time – late spring, when winter wheat was heavy with promise and corn was just reaching hopefully toward the Kansas sky.

The handwriting on one postcard tells of a man named Basil looking at land near Table Rock, that distinctive natural formation that had guided settlers for generations. What kind of optimism – or desperation – would drive someone to consider investing in farmland so soon after such devastating floods? Yet records suggest he wasn’t alone. Land transactions continued in Republic County through 1908 and 1909, some at distressed prices from farmers ready to seek fortune elsewhere, others at premium prices for higher ground.

The flood’s waters eventually receded, leaving behind debris and difficult deliberations. Farmers have always had to gamble with nature. The rich soils of river valleys are worth the risk of occasional flooding – until they’re not.

These brothers – the postcard photographers – couldn’t know that the 1908 flood was merely a prelude. The Republican River would prove its power again and again, most catastrophically in 1935, when a flood of biblical proportions would transform the valley once more. Families who chose to stay after 1908, who rebuilt and reinvested, would face nature’s judgment again.

Looking at these century-old images, we see more than just disaster photography. We see evidence of critical decisions made in the aftermath of catastrophe. Someone was behind that camera, documenting not just the destruction but the dilemma – to stay or go, to rebuild or retreat, to trust in the river’s bounty or fear its fury. The unknown photographer used the latest technology – AZO photo paper, a Kodak camera – to capture and distribute these images of nature’s disruption of human endeavor.

We don’t know if Basil bought that land near Table Rock. The brothers’ identities and their immediate choices are lost to history. But we know that farming continued and that people kept living along the Republican River despite all they had seen. Each generation seems to make its own peace with nature’s risks, balancing the promise of fertile valleys against a river’s wrath.