Deep in the rugged canyons where the Salt River carves through Arizona’s Superstition Mountains, the story of Western water management took shape. This commemorative postcard set, printed in the 2000s, features century-old government documentary photographs that reveal the effort.

The construction of Roosevelt Dam, beginning in 1906, marked not just an engineering milestone but a fundamental shift in how humans would reshape the American West. This massive undertaking would transform both the physical landscape and the social fabric of central Arizona, setting patterns of development that continue to influence the region today.

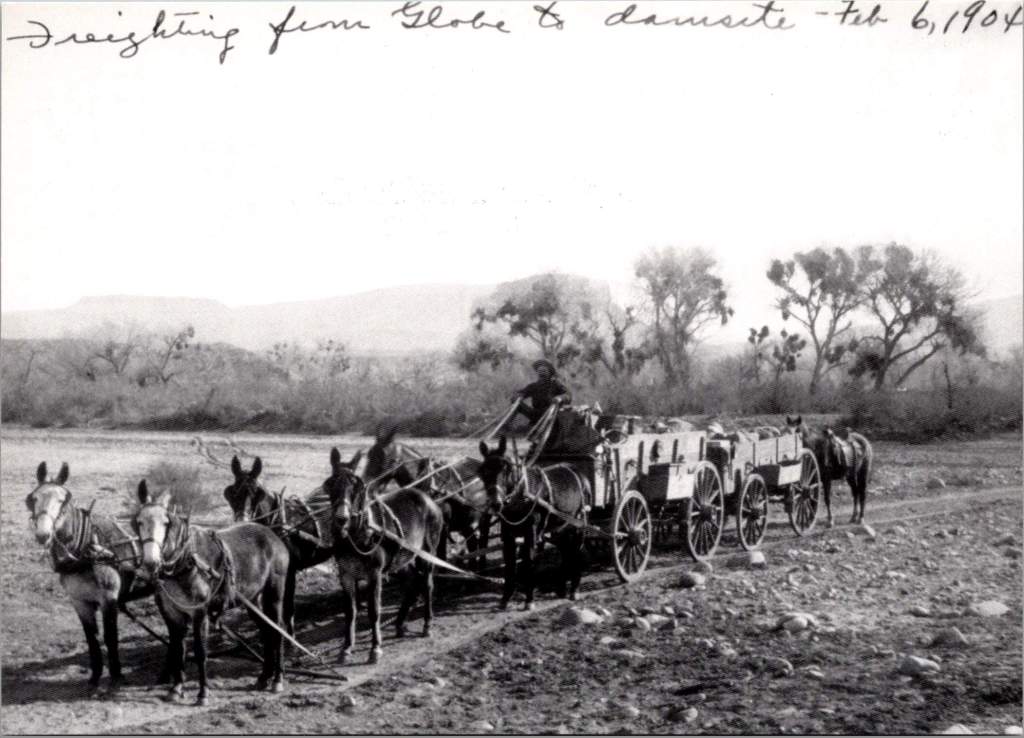

The logistics of construction proved nearly as challenging as the engineering. Materials had to travel either along the Apache Trail, a 60-mile road from Mesa carved from ancient Indian paths, or via a primitive 40-mile trail from Globe. The isolation of the site forced engineers to think creatively about resource management. They solved the critical cement supply problem by establishing an on-site manufacturing facility, a decision that would save over $460,000 (equivalent to more than $13 million today) while ensuring consistent quality control. The photographs show workers carefully weighing and sacking cement in bags marked “U.S.R.S.,” each bag representing both technical progress and economic pragmatism.

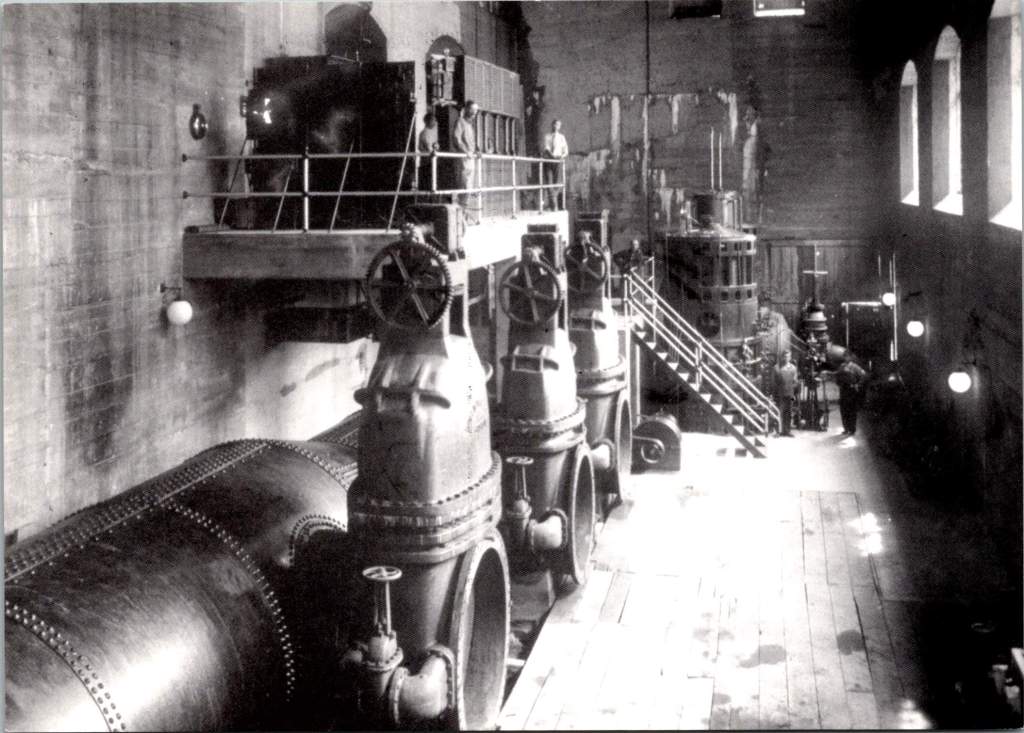

By 1909, the Roosevelt Dam Power House demonstrated another innovative aspect of the project. Housing five 900kW generators and one 5000kW generator, the facility would produce 45,000 kW of electricity by 1912, providing power to Phoenix and surrounding communities. This early integration of water management and power generation established a pattern that would shape the region’s development for decades to come.

The dam site itself presented formidable challenges that would test the limits of early 20th-century engineering. Rising nearly 280 feet from bedrock, Roosevelt Dam required innovative solutions at every stage of construction. Hydraulic drill operators, their equipment visible in historic photographs from the Walter J. Lubken Collection, faced the initial challenge of preparing foundations in solid rock. These drills, powered by compressed air, bored holes for dynamite charges that would help create the dam’s massive footprint. The rhythmic sound of their work echoed through the canyon, marking the beginning of a new era in desert water management.

Downstream from Roosevelt, engineers faced a different challenge at Granite Reef Dam. Here, nature provided a crucial advantage in the form of a natural granite reef crossing the river valley. This geological feature offered an ideal foundation for a diversion structure, but working with the hard granite required specialized techniques. Electric U.S. Reclamation Service trains, captured in the historical photographs, transported heavy equipment and materials along the construction site. The completed structure served as the crucial junction point where Roosevelt Dam’s controlled releases would be divided between the Arizona Canal to the north and the South Canal system.

As water flows west from the Superstition Mountains, it enters an increasingly engineered landscape that reveals the ingenuity of early water managers. Near Apache Junction, the canal system had to navigate complex terrain while maintaining the precise gradients necessary for gravity-fed water delivery. Engineers faced a delicate balancing act: the water needed to drop approximately one foot per mile while following natural contours, a requirement that helped determine the location of many early East Valley communities. These seemingly simple measurements would shape development patterns for generations to come.

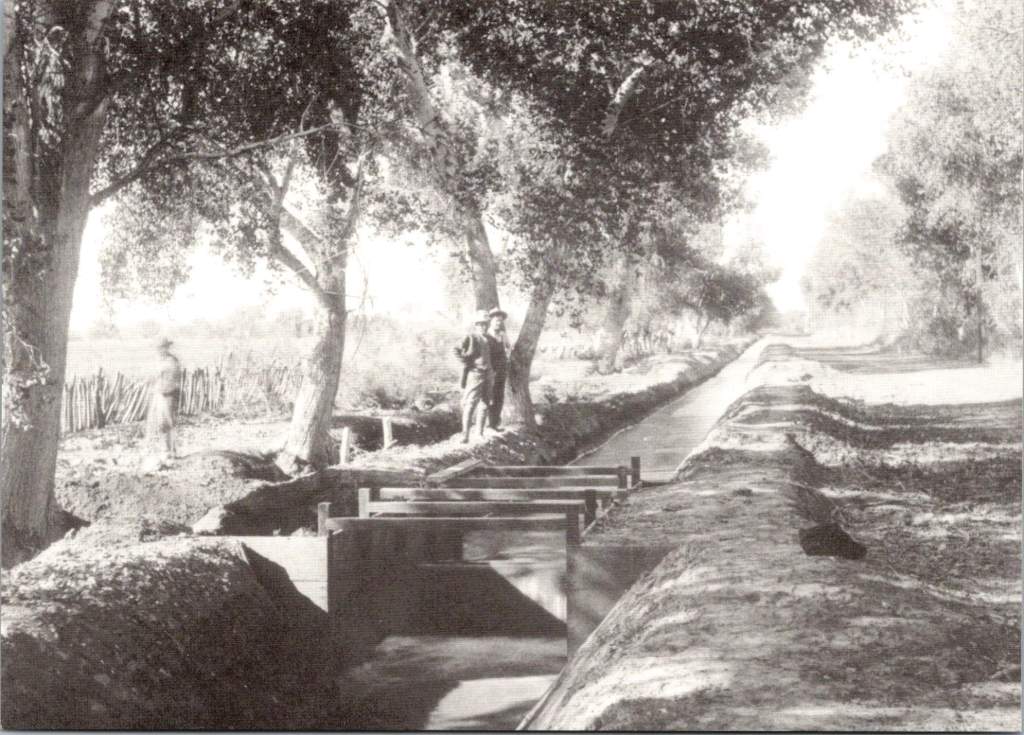

In Mesa, the system develops additional complexity as it moves through what was once some of Arizona’s most productive agricultural land. The Mesa Canal, dating from territorial days and improved by the Reclamation Service, demonstrates how engineers adapted existing irrigation works into a modern water delivery system.

Near what is now Mesa Community College, the Western Canal branches off, beginning a complex network of distribution that would support the citrus groves and cotton fields that once dominated the landscape. The concrete control gates, many dating from WPA-era improvements in the 1930s, stand as testament to the system’s durability. Each gate represented a critical control point where trusted zanjeros (ditch riders) could manage water delivery with remarkable precision, despite using what we would now consider primitive technology.

As the water system enters Tempe, it reveals layers of engineering history that mirror the city’s transformation from agricultural community to urban center. The Kyrene agricultural district, served by the Western Canal, demonstrates how early engineers maximized gravity-fed irrigation through careful grading and channel placement. The canal’s gradient had to be precisely maintained while following natural contours that would allow for efficient water delivery to agricultural fields. Complex control structures, still visible today near major arterial streets, could be adjusted to deliver specific amounts of water into lateral ditches. These laterals, running north-south at roughly quarter-mile intervals, created the framework that would later influence urban development patterns.

The post-war boom of the 1950s and ’60s presented Tempe’s engineers with a new challenge: how to adapt an agricultural water delivery system for urban use while preserving valuable water rights. Under Arizona water law, rights could be lost if water wasn’t being put to “beneficial use.” This legal framework drove many engineering decisions during the transition period, leading to creative solutions that would shape the modern landscape.

The 1961 development of the Shalimar Golf Course, located between McClintock and Price Roads and between Broadway and Southern, exemplifies the engineering solutions of this era. The course’s design worked within the existing irrigation framework, utilizing lateral ditches that had previously served agricultural fields. The layout preserved the crucial north-south water delivery patterns while adapting them for recreational use.

The late twentieth century brought new approaches to water management that would have amazed the early USRS engineers. At Arizona Falls, located at 56th Street and Indian School Road, modern engineers found a way to honor historical infrastructure while adding contemporary functionality. The site’s 20-foot drop in the Arizona Canal had once powered ice production in the 1890s, helping early Phoenix residents cope with desert summers. Today, this same drop has been transformed into both public art installation and hydroelectric facility, with specially designed turbines that can operate efficiently despite varying water levels. The project demonstrates how historical water infrastructure can be reimagined to serve modern needs while preserving connections to the past.

Perhaps no modern project better exemplifies creative water engineering than Scottsdale’s Indian Bend Wash. This 11-mile greenbelt fundamentally changed how engineers approach flood control in urban areas. Instead of constructing traditional concrete channels that rush water away as quickly as possible, engineers designed a system that mimics natural watershed functions while providing recreational space. The engineering may appear simple to casual observers, but it represents sophisticated water management. Graduated slopes slow flood waters naturally, while carefully calculated retention areas hold excess water until it can safely drain or percolate into the groundwater. At other times, these same spaces serve as golf courses, parks, and bike paths, making the infrastructure an integral part of community life.

The creation of Tempe Town Lake in the 1990s marked perhaps the most ambitious modern reengineering of the Valley’s water infrastructure. Engineers faced multiple complex challenges: maintaining water quality in an artificial lake subject to intense desert sun, managing sediment that once flowed freely down the Salt River, and creating a system that could handle both regular flows and occasional floods. The innovative rubber dam system, recently replaced with hydraulically operated steel gates, had to maintain a consistent lake level while allowing for flood releases during major storm events. What appears on the surface as a simple recreational amenity actually represents one of the most complex water management systems in the Southwest.

The Valley’s own golf courses have evolved from simple users of flood irrigation to pioneers in water conservation technology. Early courses relied on traditional flooding methods inherited from agriculture, and modern facilities employ sophisticated systems that can adjust water delivery down to individual sprinkler heads. Courses along the Western Canal system, such as Dobson Ranch in Mesa, now integrate stormwater capture, irrigation storage, and groundwater recharge into their operations. Their water hazards serve double duty as holding ponds in an intricate water management system that would have seemed like science fiction to the early zanjeros.

Today’s systems employ real-time monitoring technology, allowing operators to adjust water flows remotely in response to changing demands and weather conditions. Computer-controlled irrigation systems at golf courses and parks use weather data, soil moisture sensors, and evapotranspiration calculations to deliver precisely the right amount of water at the right time. These innovations grew from decades of experience managing water in an arid environment, building upon the foundation laid by those early infrastructure projects.

When Walter J. Lubken raised his camera to photograph construction at Roosevelt Dam, he was documenting more than just a construction project. His photographs captured the transformation of the American West from a challenging frontier to a managed landscape. The Bureau of Reclamation’s commitment to thorough photographic documentation served multiple purposes. Engineers could use the images to track construction progress and solve problems. Administrators in Washington could monitor their investment in distant territories. Sheep grazing along canal banks shows how engineers creatively solved maintenance problems while supporting local agriculture. Perhaps most importantly, these photographs reveal important historical details of how federal infrastructure projects were reshaping the American landscape.

These photographs remind us that water management is ultimately about people: the workers who built the systems, the farmers who used them, and the communities that grew around them. The photo of early canals being excavated by horse and manual labor provides striking contrast with modern construction methods. These historical documents help us understand both how far we’ve come and how much we owe to early innovation.

The Bureau’s decision to commemorate these images in a 2002 postcard set invites us to consider how past engineering decisions continue to shape our present. Every canal, dam, and pipeline represents decisions made by people trying to build better communities. As we face modern challenges like climate change and population growth, these historical images encourage us to think both critically and creatively about water management.

Today’s water managers are creating their own documentation for future generations to study. Digital sensors transmit continuous data about water flow, quality, and usage. Satellite imagery tracks changes in groundwater levels and vegetation patterns. Modern projects like Tempe Town Lake and the Indian Bend Wash are extensively documented not just in photographs but in environmental impact studies, engineering plans, and public meeting records. This documentation will help future generations understand both our achievements and our challenges.

Today’s innovations – whether in golf course irrigation, urban stream restoration, or water recycling – are part of a continuing story of human ingenuity in the face of environmental challenges. Our task is to document our work, both our successes and our mistakes. What will they learn from examining our current water management projects? Perhaps they’ll examine how golf courses became laboratories for water conservation technology.

Like our predecessors, we are trying to balance human needs with environmental stewardship, technological capability with sustainable practice, and individual interests with community benefit. This long view of history reminds us that infrastructure is not just about providing resources today – it’s about designing our desert futures a century from now.