Edmund Schafer settled into his chair, adjusting the dials of his ham radio. The basement smelled of warm vacuum tubes and coffee. Outside, a late March snow fell silently over the South Dakota prairie, but in this windowless sanctuary, the world grew larger and closer in the amber glow of dials and distant voices.

Edmund reached for the envelope that arrived in yesterday’s mail. Ten new QSL cards. Ten confirmations that somewhere, someone had heard his brief signals across the radio waves.

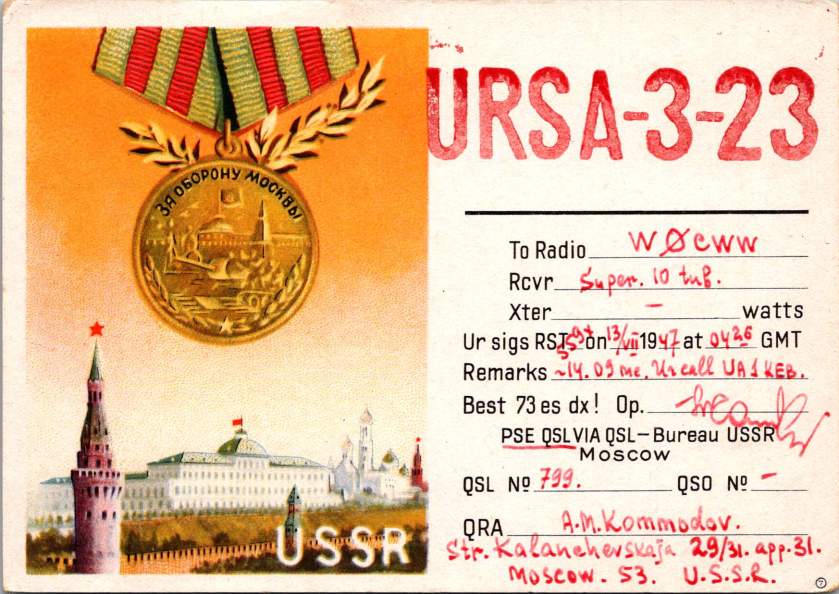

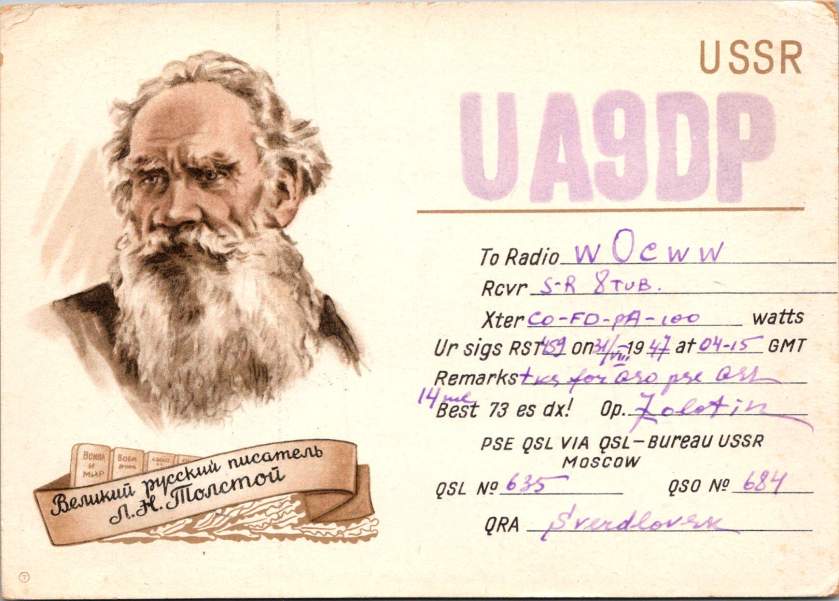

An illustration of a reindeer-drawn sled against a map of the Arctic caught his eye, the bold callsign UA1KEB dominating the design. “USSR Polar Radio Club, Amderma City,” he read aloud. The contact was from last July, but the card had taken eight months to reach him through Moscow. The miracle wasn’t just the thousands of miles the signal had traveled, but that this evidence of connection had crossed the increasingly tense political boundaries of 1947.

Edmund slipped the card into his album, next to other Soviet contacts. The pages were growing thick with paper confirmations – New Zealand, England, Spain, and France – each a tangible memento of his voice reaching across impossible distances.

He turned to his rig – a recently acquired transmitter paired with a war-surplus receiver he modified himself. The hour was late, but 20 meters might still be open to the Pacific. There was always one more contact to make, one more card to add to his collection.

Tech Tactic to Tradition

The QSL card evolved from necessity into tradition, from a modest technical confirmation into a beloved cultural artifact.

In the early days of radio, pioneers weren’t concerned with souvenirs – they were trying to prove wireless communication was possible at all. By the early 1900s, amateurs began experimenting with their own stations, communicating in Morse code across increasing distances. The problem was verification – how could you prove you’d actually contacted someone thousands of miles away?

The answer came in 1916 when wireless operators began mailing confirmation postcards. The term “QSL” comes from the Q-code system developed for commercial Morse communication – “QSL” meaning “I confirm receipt of your transmission.”

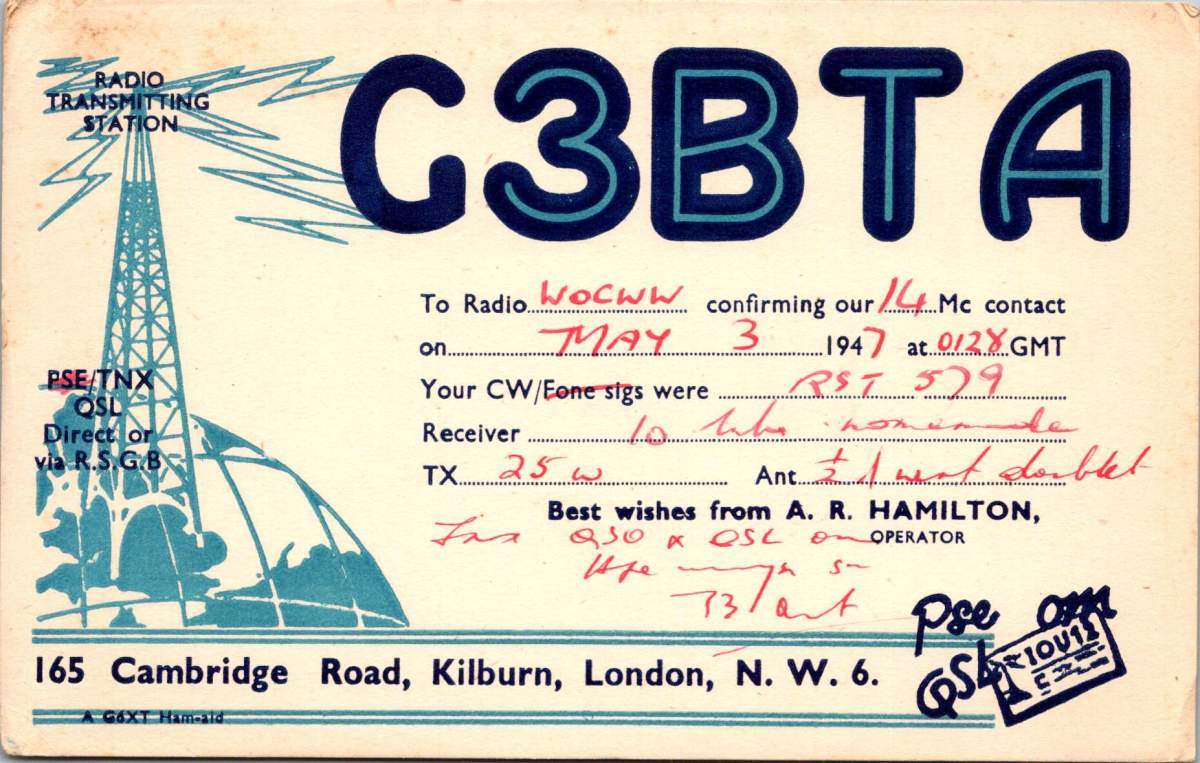

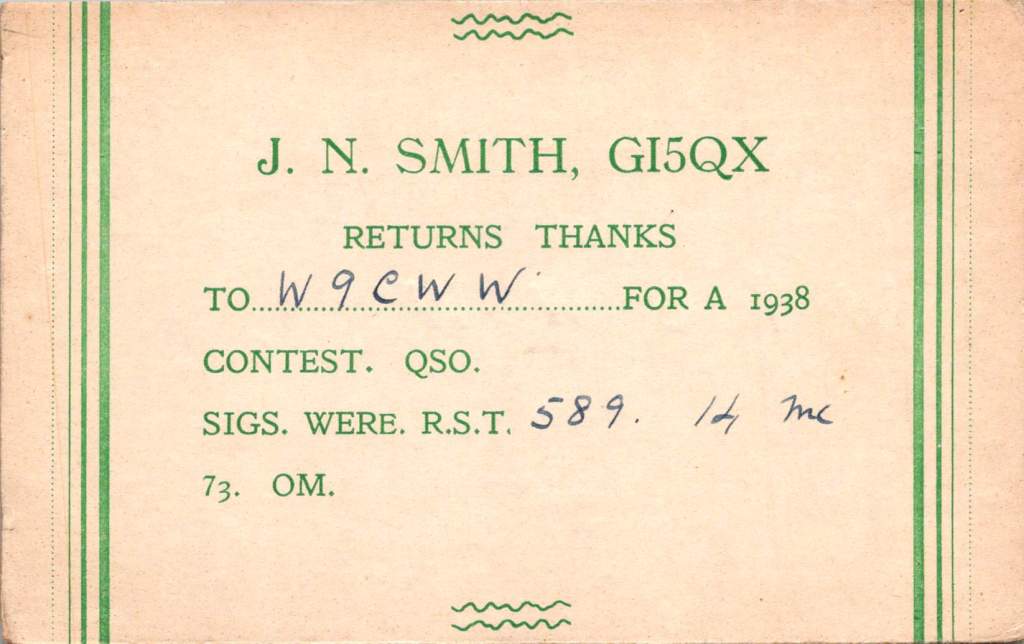

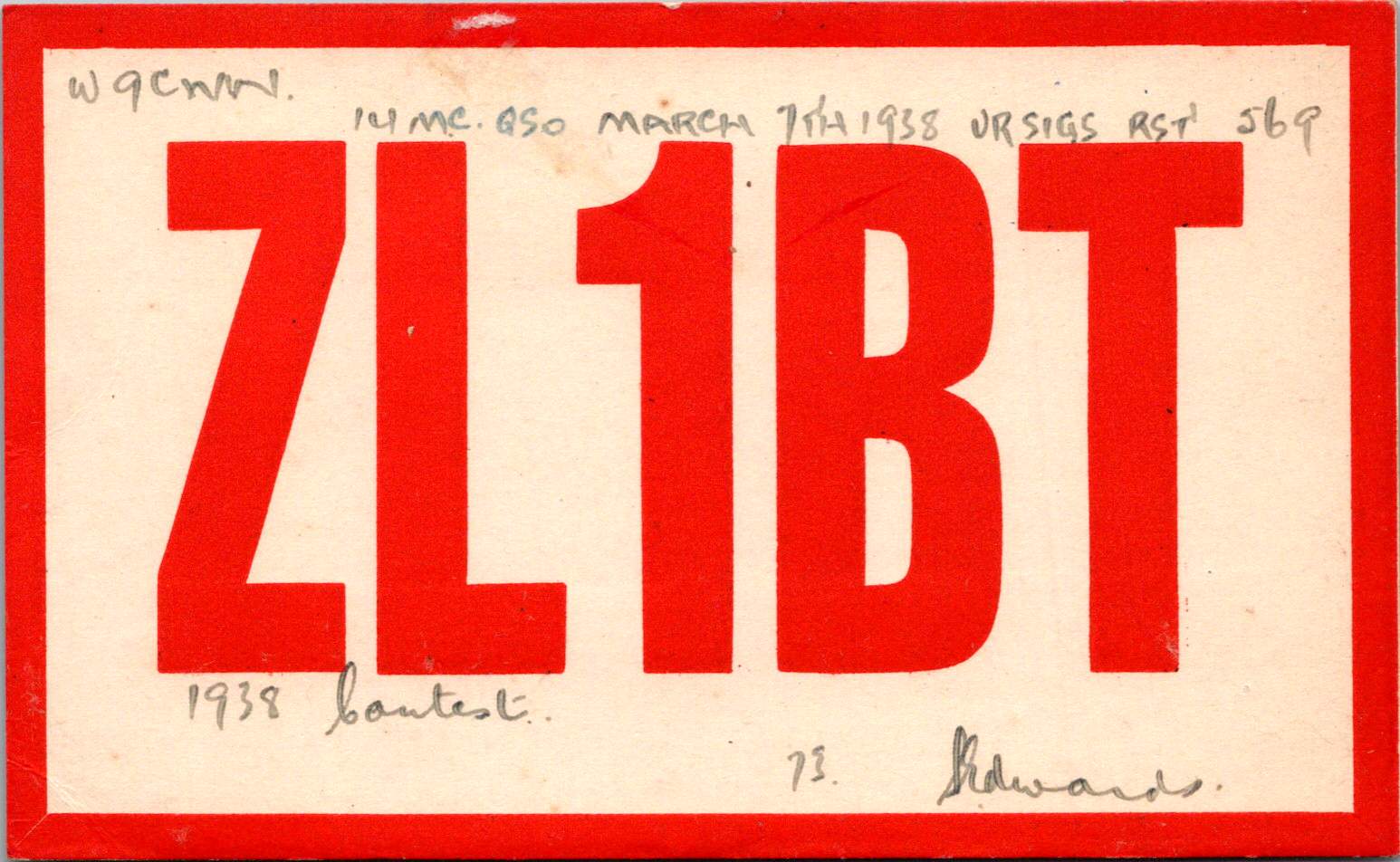

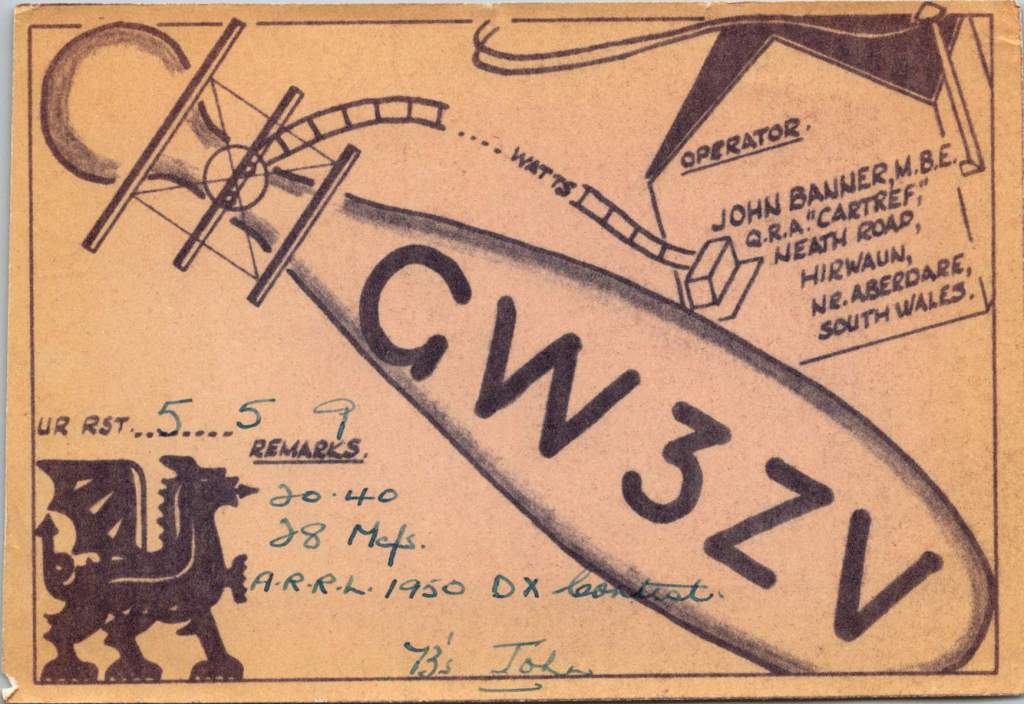

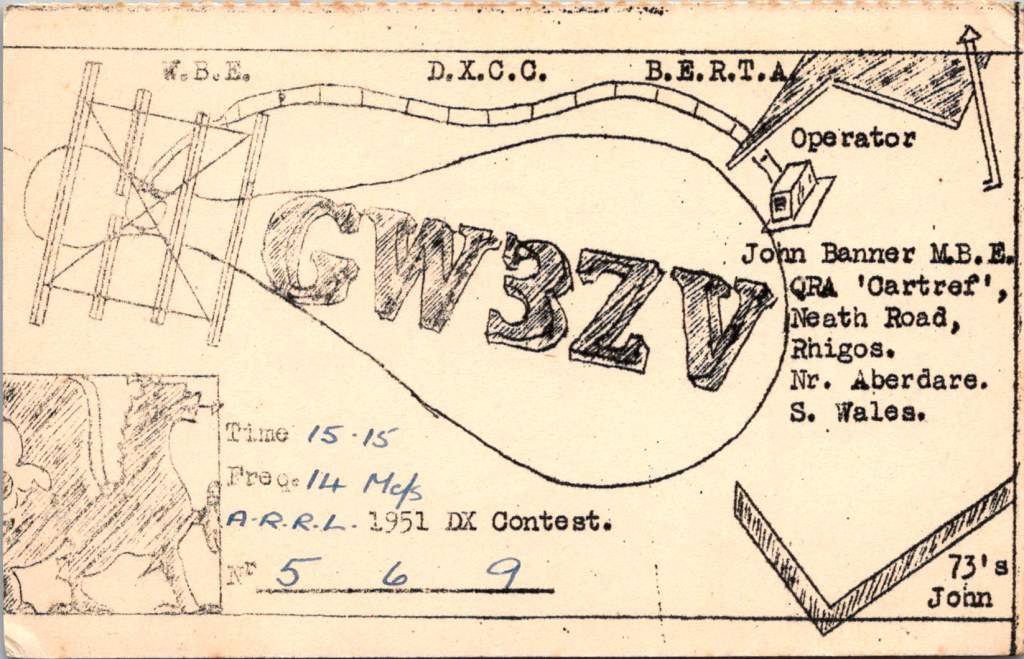

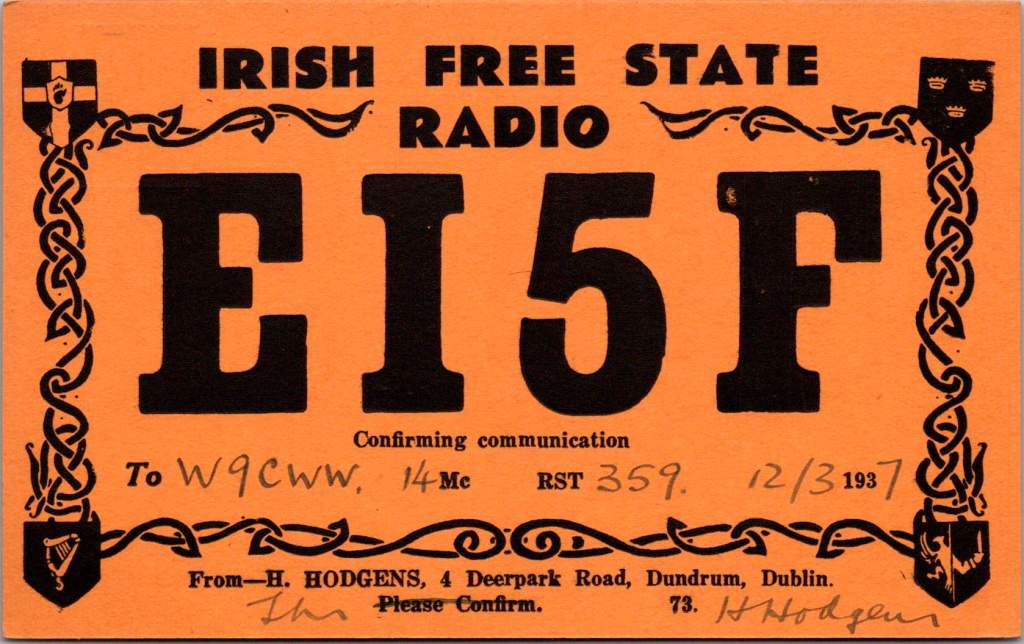

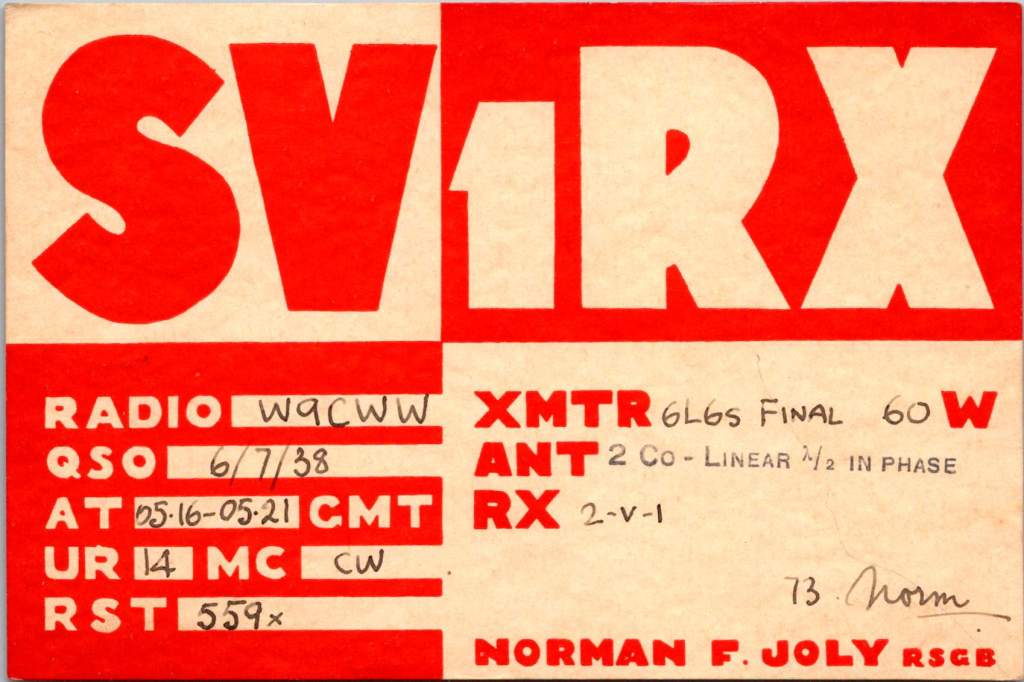

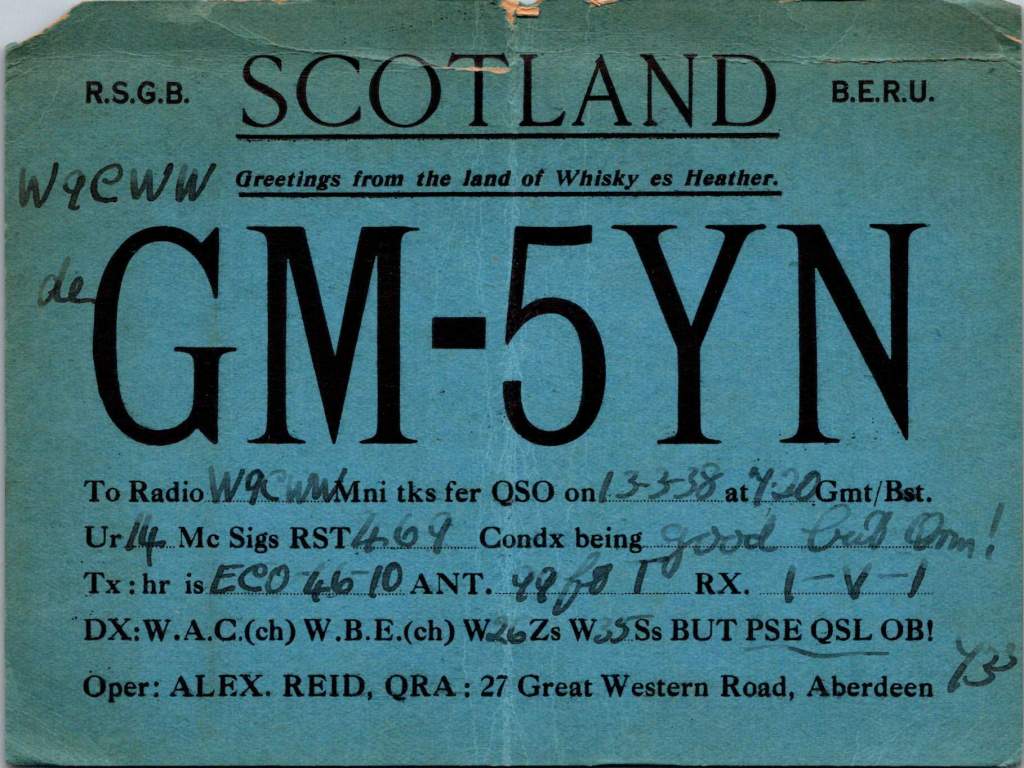

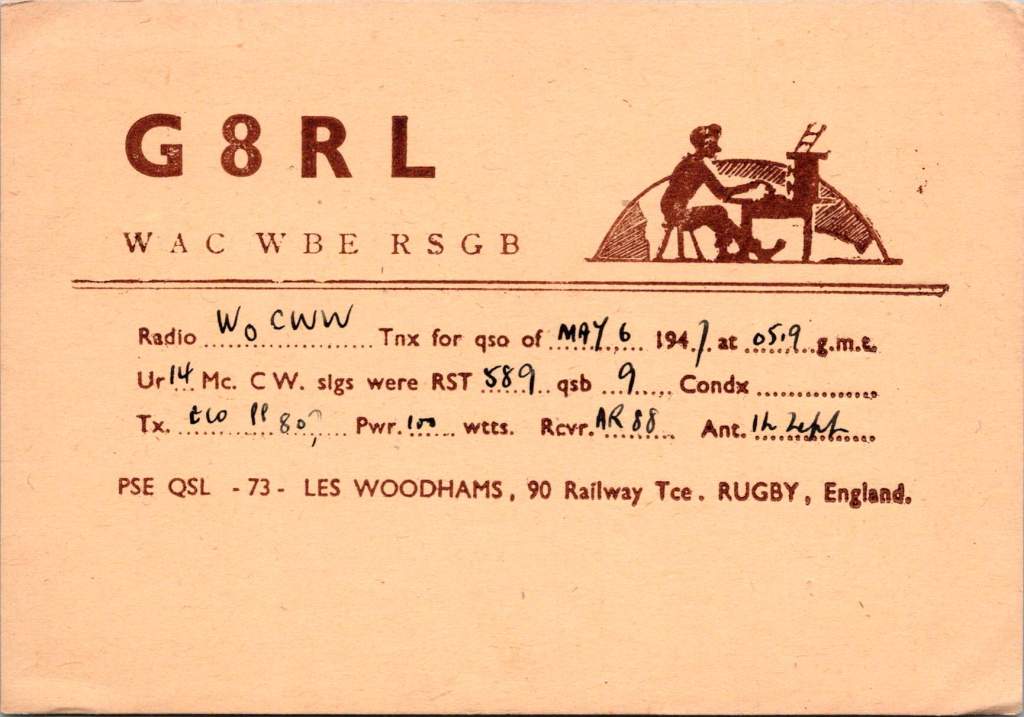

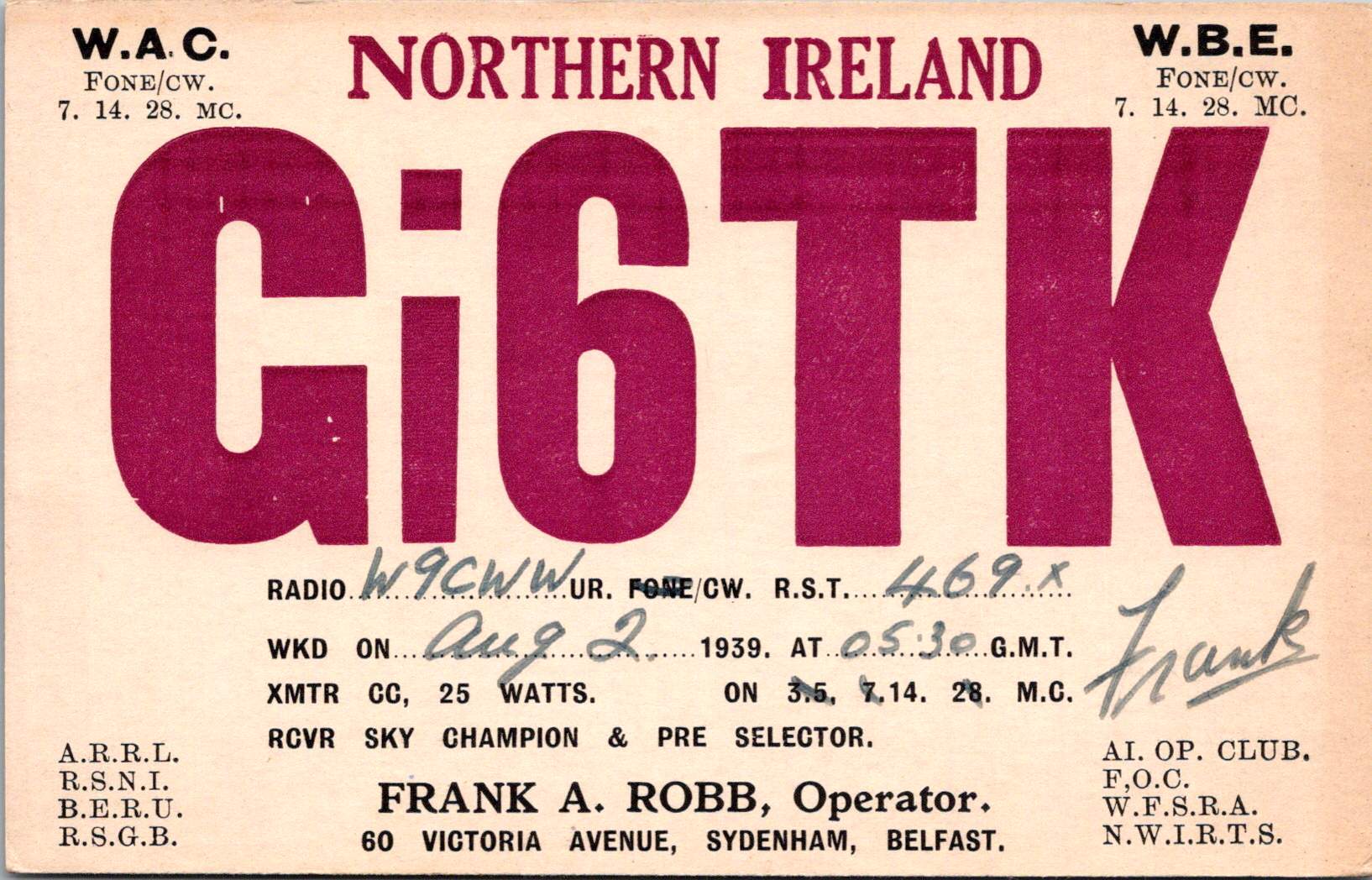

By the 1920s, these cards included standard details: callsign, date, time, frequency, signal report, and equipment used. Within these parameters, personal expression flourished. Some cards were professionally printed with striking designs; others were hand-drawn or modified from templates. Cards became proof of operating prowess, driving operators to expand their geographical reach.

By the 1930s, collecting QSL cards became a pursuit in itself. The American Radio Relay League (ARRL) began offering awards like the DX Century Club for contacting and confirming 100 countries.

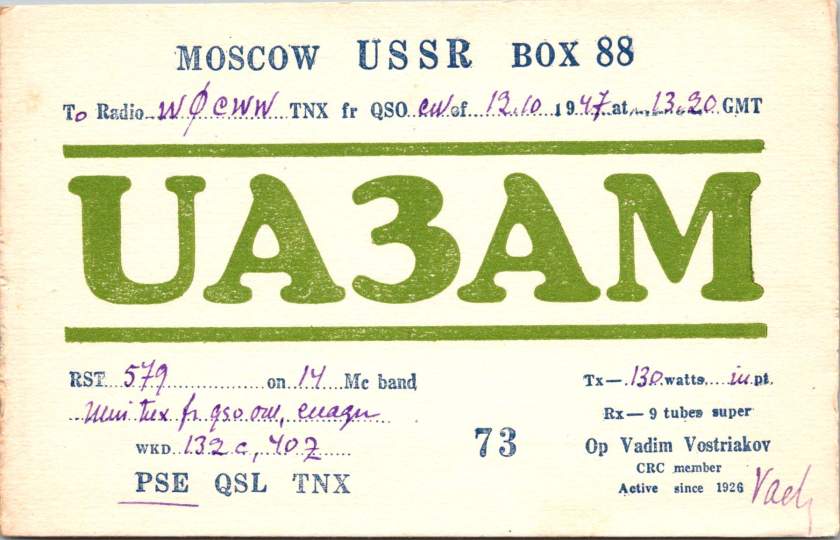

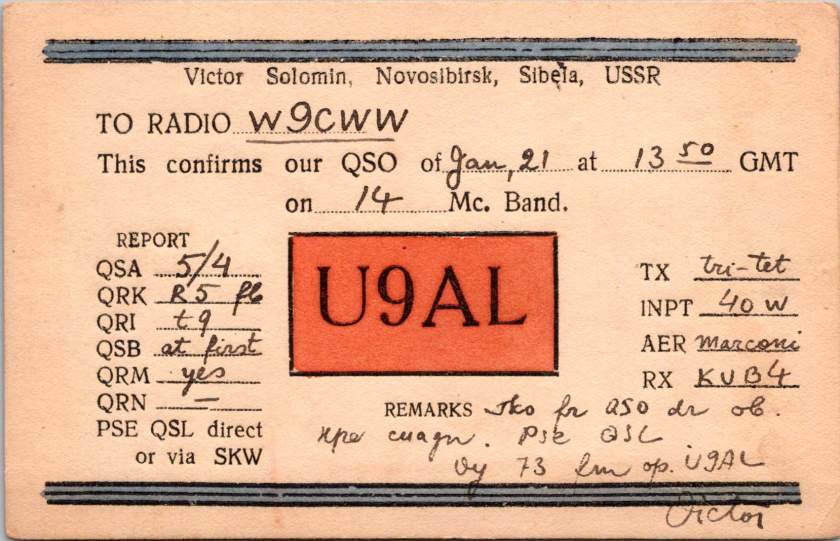

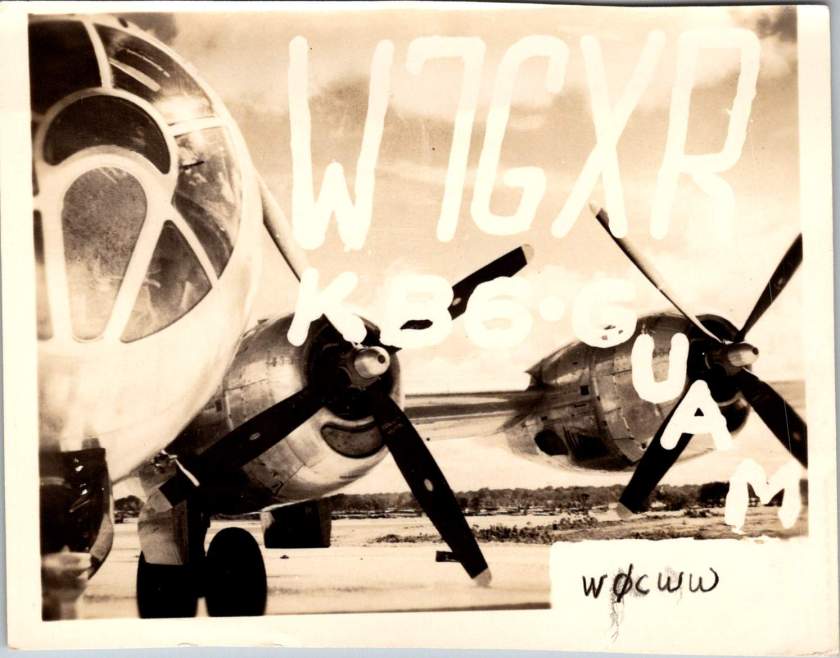

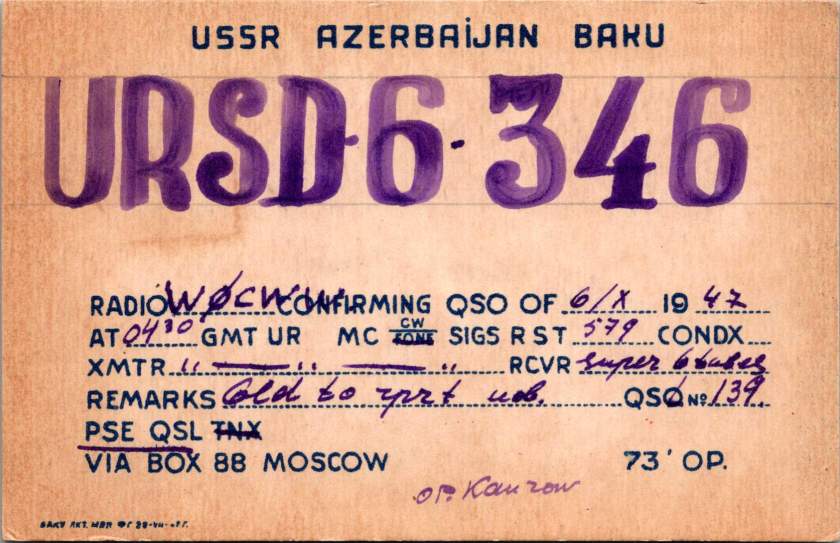

The selection of cards shown here represents a golden age of QSL. Charles A. Pine (W9CWW) from Leavenworth, Kansas and Edmund Schafer (W0CWW) from White, South Dakota had cards from pre-Vietnam Hanoi, pre-war Madeira Island, and Ecuador. Their combined collection of 100 cards documents contacts from the mid-1930s through the post-WWII era, spanning a critical period in world history.

The Culture of Early Operators

The amateur radio community of the early 20th century was a global technical fraternity with its own language, ethics, and hierarchies of achievement.

The airwaves were a great equalizer. A factory worker could chat with a king if both were hams. King Hussein of Jordan (JY1) and Barry Goldwater (K7UGA) were both avid operators who exchanged QSL cards with ordinary hams worldwide.

The culture valued technical expertise above all. Operators often built their equipment from scratch, learning electronics through experimentation. Magazines like QST and CQ provided schematics and technical advice, while experienced hams (called “Elmers” in ham parlance) mentored newcomers.

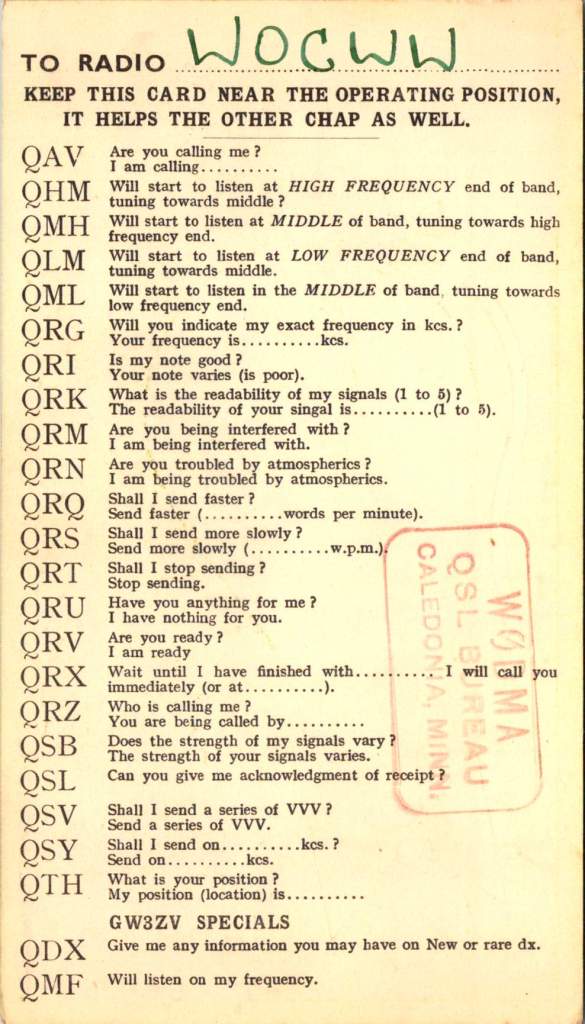

Ham radio developed specialized terminology and shorthand to overcome communication limitations. Q-codes provided standardized questions and answers (QTH for location, QRM for interference). Technical abbreviations created efficient communication even across language barriers.

For American hams like Charles Pine, the W9 prefix identified his Midwestern location. Edmund Schafer operated as W0CWW from South Dakota. Worldwide, prefixes denoted nationality – G for Britain, ZL for New Zealand, CT3 for Madeira – creating an addressing system that transcended postal boundaries.

Operating etiquette was strictly observed. Calling “CQ” (a general call for any station) required listening first. Signal reports followed the RST system (Readability, Signal strength, Tone) with numerical values. Politeness was paramount and helping during emergencies was considered duty.

Radio’s Wartime Role

Amateur radio’s relationship with global conflict is complex. During both World Wars, governments shut down amateur operations, concerned about security and interference with military communications. Paradoxically, these shutdowns strengthened ham radio for decades afterward.

When America entered World War II, there were approximately 60,000 licensed amateurs in the United States. Most surrendered their equipment or had it sealed for the duration.

The military needed radio operators desperately. Hams were pre-trained and understood radio propagation, troubleshooting, and operating procedures. The U.S. Army Signal Corps, Navy, and Army Air Forces absorbed thousands of amateur operators. Others served as radio operators on merchant vessels. Many with aptitude were identified for communications training at facilities like Camp Crowder in Missouri.

When peace came in 1945, amateurs returned to the airwaves with unprecedented technical knowledge. War surplus equipment flooded the market at bargain prices. Advanced technologies developed for military applications became available to civilians. The result was an amateur radio boom.

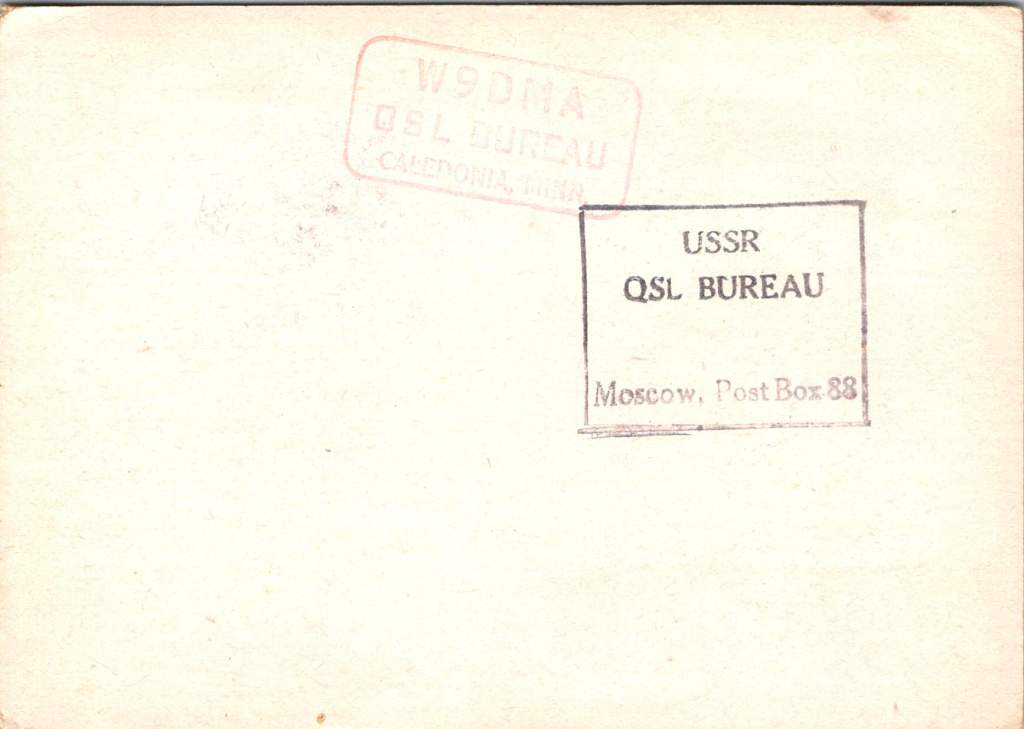

The Soviet QSL cards represent a remarkable Cold War footnote. Despite growing tensions, ham radio operators maintained fragile connections across political divides. Soviet hams could contact Western operators, though conversations were typically limited to technical exchanges.

Arctic radio operations supported Soviet scientific and military activities in the far north. That such a station would confirm contacts with American operators shows how the technical fraternity of radio sometimes transcended geopolitics. The mandatory routing of Soviet QSLs through “Box 88, Moscow” – the central receiving point under government supervision – reveals the controls in place.

How QSL Cards Found Their Way

Getting a QSL card from a Soviet polar station to Kansas or South Dakota in 1947 was no simple matter. The journey these cards took reflects the ingenious systems hams developed to exchange confirmations globally.

There were two primary methods to exchange QSLs: direct and via bureau.

The direct method was straightforward but expensive: mail your card directly to the operator’s address, often including return postage. This worked well for domestic contacts but became problematic internationally due to exchange rates and language barriers.

The bureau system, developed in the 1930s, offered an efficient alternative. National radio organizations established central clearing houses for QSL cards. American hams would send cards for foreign contacts to the ARRL’s outgoing bureau, sorted by country. The ARRL would forward these in bulk to counterpart organizations overseas, dramatically reducing postage costs.

For incoming cards, operators maintained envelopes at their district’s incoming bureau. When enough cards accumulated for a particular operator, they’d be forwarded in batches.

The notation “PSE QSL” seen on many cards was a request for reciprocal confirmation. “73” – meaning “best regards” in traditional telegrapher’s shorthand – often closed these miniature correspondences.

The Collector’s Pursuit

For Charles Pine, Edmund Schafer, and their contemporaries, collecting QSL cards served multiple purposes beyond simple confirmation of contacts.

First was achievement recognition. The ARRL’s DX Century Club award required written proof of contacts with 100 countries. Other awards like Worked All States (WAS) similarly required QSL confirmation.

The cards also served as geographic education. Many operators became amateur geographers through their radio contacts, developing detailed knowledge of world geography and political boundaries.

Cards from 1938-39 represent the final moments of peacetime DXing before war silenced international amateur communications for years. Soviet contacts capture a brief window when East-West amateur communications were still possible, soon to be constrained by Cold War tensions.

For modern collectors, vintage QSL cards document the history of global communication. They show the evolution of electronic technology, international relations, and graphic design. The most sought-after cards come from “deleted entities” – places that no longer exist as independent radio countries, like Netherlands East Indies or pre-independence colonies.

Amateur radio historians particularly value cards with technical annotations about equipment and propagation conditions. The UA3TL card noting the use of a homebrew transmitter tells us about Soviet amateur technology in the postwar period – a technical snapshot from behind the Iron Curtain.

Invisible Networks Made Visible

This combined collection captures a pivotal era in communications history. The cards from pre-war contacts document the international amateur community before global conflict disrupted it. The post-war Soviet cards illustrate how radio enthusiasts rebuilt connections even as political tensions rose.

Today, digital modes and internet-linked systems have transformed amateur radio. Electronic confirmations have largely replaced paper QSLs for award purposes. Yet physical cards persist, with thousands still exchanged annually.

Museums and archives increasingly recognize the historical value of these humble confirmations. The Smithsonian, the ARRL’s heritage collection, and specialized radio museums preserve QSL collections as records of technological and cultural history.

As Edmund prepared for one more contact that night in 1947, the airwaves continued carrying voices and code around a planet divided by new political realities yet united by individual curiosity. The QSL cards, with their bright colors and technical notations, made visible what was otherwise hard to grasp – the human connections made possible when technology and enthusiasm overcome distance and difference.