Through three preserved postcards from the early 1900s, we discover how every point of contact becomes a sacred center, a middle ground where hearts meet across distances both physical and emotional. Each yellowed card, with its carefully penned message, reminds us that we are all perpetually in the middle of things, reaching out across whatever distances separate us, making meaning in the spaces between hello and how are you?

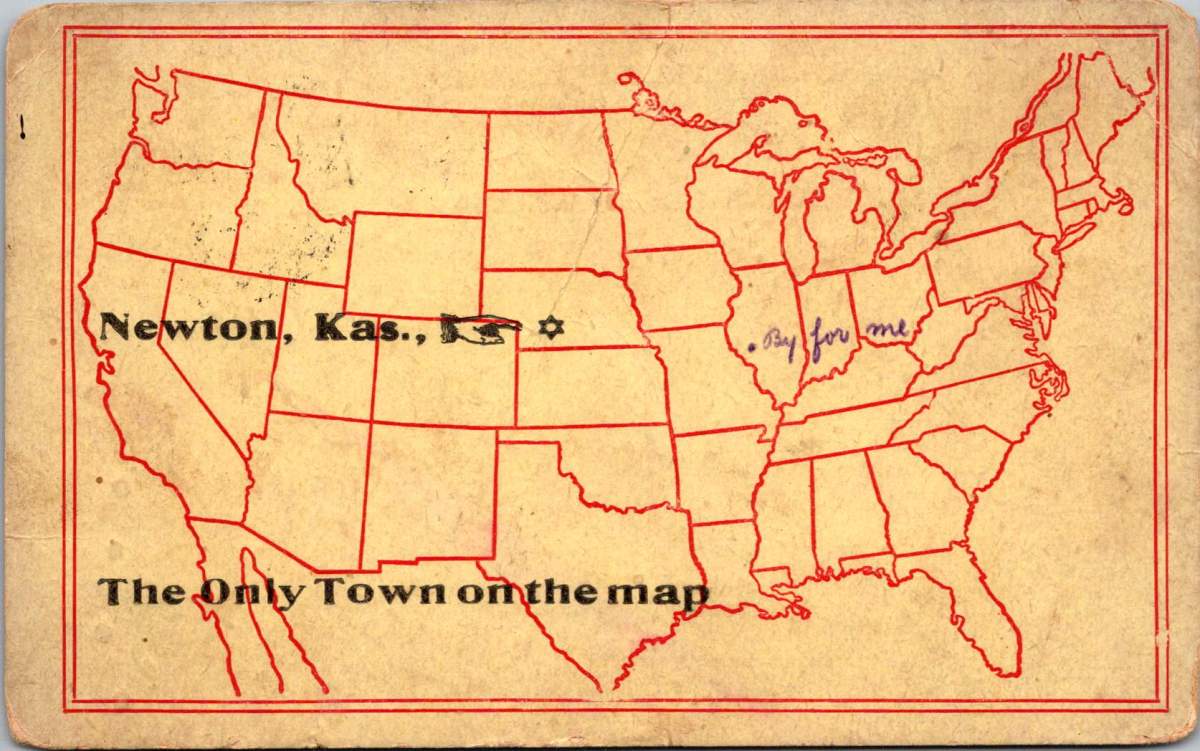

The Only Town on the Map

In Newton, Kansas, July 1908, Ed pauses between trains to write to his mother on playful postcard. A single dot on a stencil-drawn outline of the United States marks Newton as The Only Town on the map – a silly claim that also quietly captures a truth about human connection.

The humor lies in its absurdity – a blank continent save for this one dot in Kansas. Yet for Ed, in that moment, Newton truly is the center of everything, the pivot point between where he’s been and where he’s going.

Dear Mother, stopped off to change cars here for Amarillo Texas. There is where we are billed for. Got your letter at K.C. Too bad about him but he will make it ok. Am well this am, hope you and everybody else the same. Ed

He’s literally in the middle of the country, this railway town serving as his sacred center for just a few hours. There’s worry in his words about someone who’s unwell, balanced with reassurance about his own wellbeing. Even in transit, through immense uncertainty, he reaches for connection.

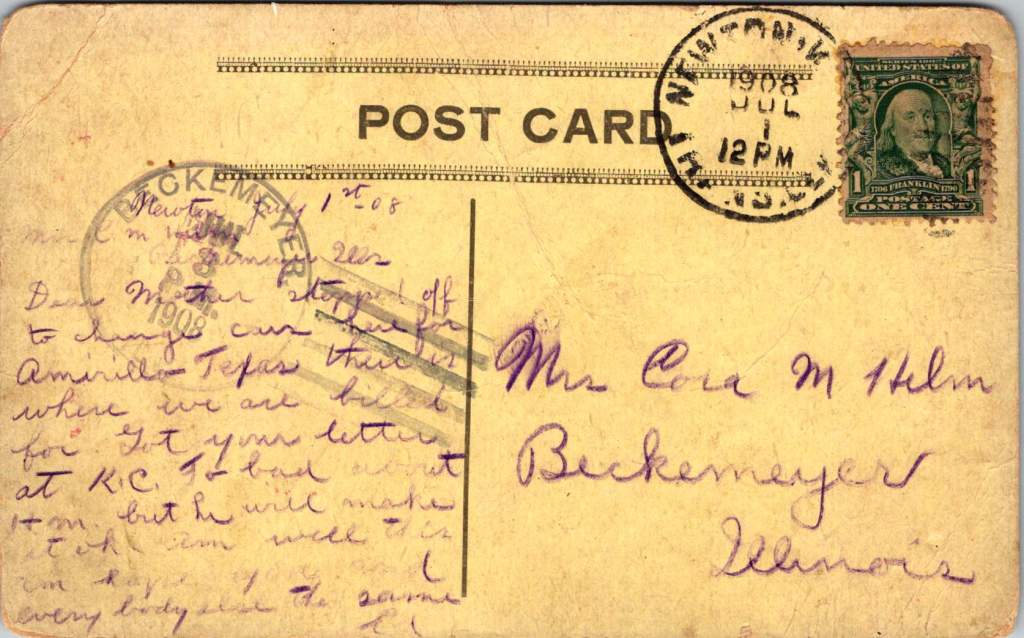

Long to Shake Your Hand Again

Two years later, in Ironton, Ohio, a young woman named Alma sends a card to Beatrice Sutphin in West Virginia. The card’s design speaks volumes: blue forget-me-nots and pink daisies frame a handshake, that polite, egalitarian gesture. Behind the clasped hands stretches a pastoral scene with water and a bridge – another symbol of connections that span distances.

“Do you love me as well as you used to, kid,” Alma writes, her playful tone reflecting the common courtesies of the day while masking a deeper yearning for reassurance. She’s navigating the creative tension of friendship across distance, using casual language and nudging humor to reach across the miles. The card itself becomes a bridge, a handshake in paper form.

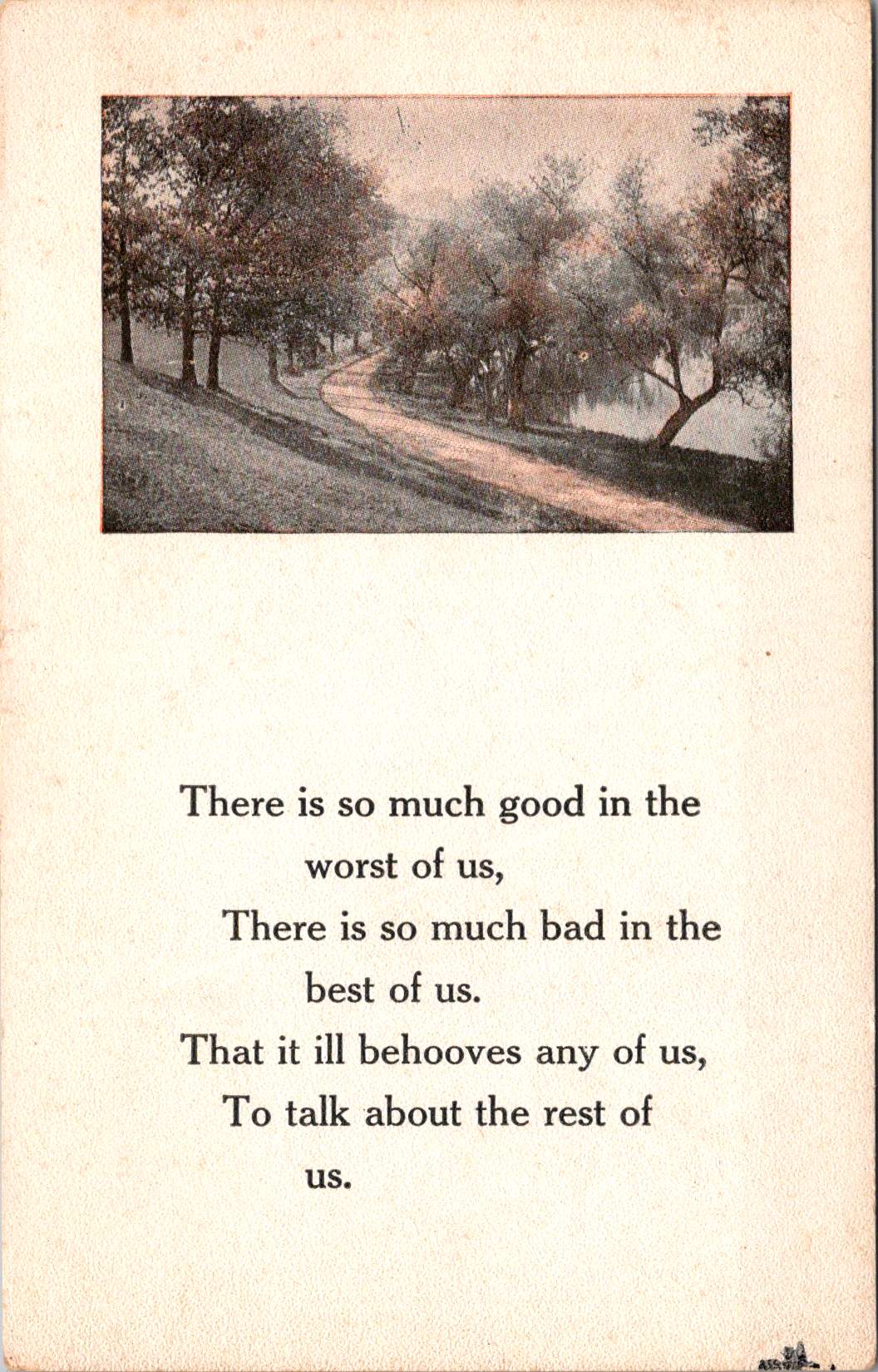

The Path Through the Trees

The third card, never mailed but carefully preserved, shows a winding path through trees, accompanied by verses about the complexity of human nature. A.E. Tillson writes to Mrs. Parsons with a note of formal sympathy, then adds a gentle joke about hosting in-laws. The message operates in that delicate middle ground between social obligation and genuine concern, between gravity and levity.

“I think of you so often,” she writes, “and hope you will be given strength to endure as the days go by.” Then, like a subtle change in musical key: “I am entertaining my mother-in-law and also my father-in-law for the second week now, but I will try to be good.”

All these years later, we are still inclined to gently inquire. Reading the messages between the lines, as they say. Do I sense a subtext here? What prevented her from sending this card? Why did she keep it long years on?

The Sacred Center

Something lies at the intersection of these three postcards, a sacred center they all circle around. It’s not serenity – each writer grapples with some form of creative tension. Ed worries about an unnamed “him” while trying to reassure his mother. Alma playfully demands affirmation of continuing friendship. A.E. Tillson balances sympathy with humor, formal phrases with personal asides.

The sacred center is the conversation itself – the eternal human drive to reach out, to connect, with even the most mundane facts. The center thrives on these noted perspectives, each writer offering their unique take, laden and layered with meaning though jotted out from a whistle stop.

These postcards are artifacts of appreciative inquiry in its most natural form. Each sender pauses in their own journey to ask: How are you? Are you well? Do you still care for me? Can I help you bear your burden? The questions themselves open up places where hearts meet and stories intertwine.

Some of us, like Ed in Newton, write from the middle of a physical journey. Others, like Alma, navigate the emotional journey of maintaining connections across distance. Still others, like A.E. Tillson, write from the complex shared ground of social obligations and genuine concerns, so often unspoken.

In Transit, In Place

Whatever the circumstance, we are always in the middle of things. There is always a before and after, always tension between where we’ve been and where we’re going, between who we were and who we hope to become. These postcards remind us that this center is not a void to be escaped but a sacred space packed with the very humble pieces of possibilities.

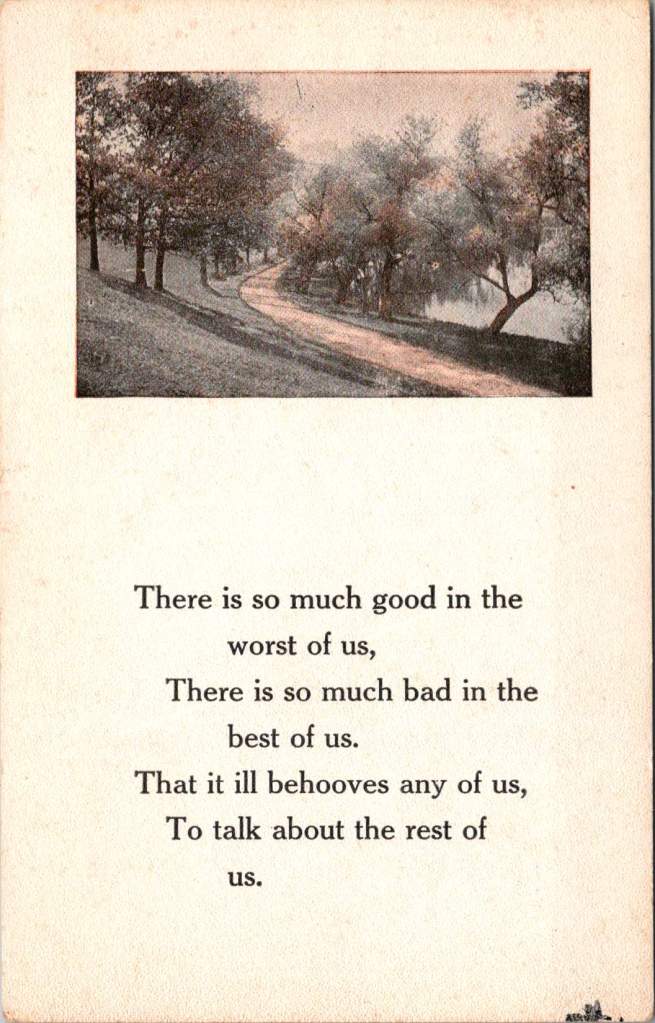

The verse on the unposted card speaks to this truth:

There is so much good in the worst of us, There is so much bad in the best of us, That it ill behooves any of us, To talk about the rest of us.

The middle is the best part – of our stories, of our journeys, of our complex relationships with others. As they say, if you’re not dead, it’s not over. The sacred center isn’t found in perfect serenity but in the creative tension of reaching out across whatever distances separate us, whether those distances are measured in railroad ties or handshakes.

These century-old postcards, with their careful penmanship and gentle inquiries, their jokes and worries and reassurances, remind us that the center holds not because it is static, but because it is constantly renewed through the sacred act of one person reaching out to another with a simple message. Here I am, in the middle of it all, thinking of you.