Careful block letters adorned the outside of a #10 envelope. George recognized Jack’s handwriting. Precise, old-fashioned, like an architect from a bygone era. Inside, George found a letter to addressed to him, and a long list of books Jack had read. Not just titles, but notes.

The Hidden Life of Trees – I like how roots connect underground.

The Mapmakers – Bird migrations mapped with ocean currents.

A Sand County Almanac – The geese made me cry.

George sat at his kitchen table, poured over the letter twice, then kept going back to it in mild wonder. The boy was thirteen. Reading natural philosophy at a level twice his age and writing elegant, matter-of-fact prose.

George now had a collection of postcards just for his grandson. He kept an eye out for anything inspired by books, libraries, explorers, architecture, and history. But today, he had a different one in mind.

Jack – Your list made my week! You remind me why books matter. Keep reading, all of life is in there. – Grandpa

George bundled up and trudged to the mailbox in the extremely cold and icy January morning. Stood there a moment, breath visible in the air, so proud of a thirteen-year-old boy who cried over geese.

The phone rang Saturday afternoon. It was Mai.

“Dad? You busy?”

“Never too busy. What’s up?”

“So—weird thing. I heard from both Derek and Marcus this week, within a day of each other.”

George set down his coffee. Mai’s brothers were also adopted from the chaos in Laos, but by different families. Mai didn’t know or remember much as a child. They’d reconnected as young adults as they discovered their shared histories. George had met Mai’s brothers only three times, at each of their weddings. Derek, the oldest, spent his early years in an orphanage before his adoption. He now runs a tech business in Palo Alto. Marcus, the youngest, grew up in a musical family and plays professional brass in traveling shows.

“That’s wonderful. Everything okay?”

“Yeah, they’re fine. Both texted out of the blue. Derek asked about the kids, Marcus asked about you. I think they’re feeling their age,” Mai chuckled.

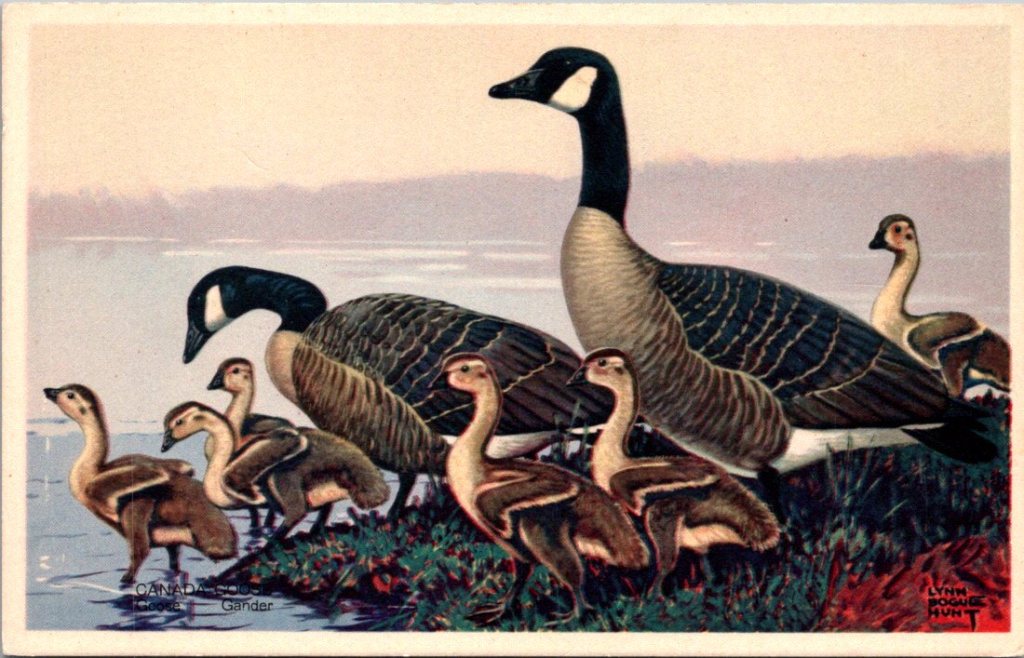

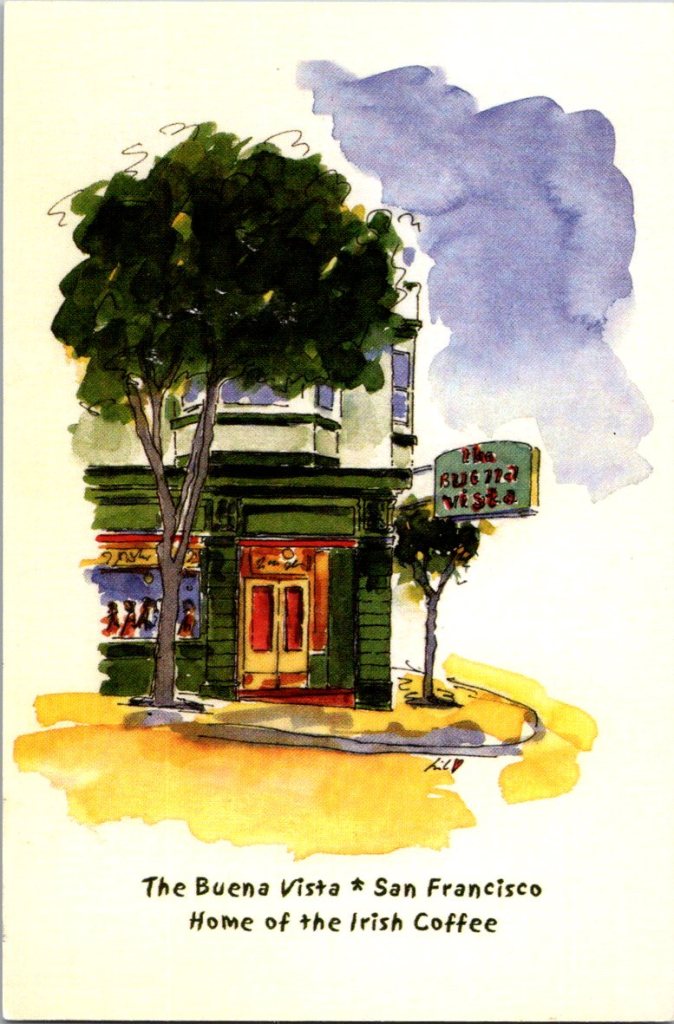

After they hung up, George sat at his table looking at his postcard stacks. He found a San Francisco classic for Derek, and an old club card from Illinois for Marcus. Relics from a jazzier time. Same short notes to both of them.

Mai says you’re doing well. Glad to hear it! – George

Nina loaded into her car early Sunday morning. Coffee in a thermos, bag full of stuff, and Mrs. Hanabusa’s advice in her head. Leave room. Her mind drifted for most of the drive, watching the sunrise over the desert and mountains to the East. She took the old road through Florence for just that reason.

Nina climbed the stairs in the worn, beige apartment complex, and knocked.

Tom opened the door looking nervous. “Hi. Come in.”

Nina noticed immediately, he was making an effort. Coffee brewing, store-bought pastries on a plate, magazines and mail in piles recently cleared from the couch. Seemed like he intended to inhabit the place, not just occupy space.

The talk was halted at first, then easier. Nina found it so strange that she grew up with the man and knew him not at all.

“I brought something,” Nina said. She pulled out all the postcards he’d sent over the years, a large batch that bulged at the seams of a padded envelope. Airport terminals, layover cities, all those airplanes. The last year had revealed so much, including the way her father had actually stayed connected in a quiet (and still insufficient) way.

“I kept them.”

“I didn’t know if you would. You weren’t always into them like we were.”

“I wasn’t. I didn’t even remember that I saved them. Found this stash looking through a bunch of old boxes, now that I know what to look for. Dad, I never made the connection before now.”

Tom smiled sheepishly, stood, went to his bedroom, came back with a shoebox full of postcards from Delia, dozens of them, saved over their entire marriage. Travel postcards from trips they’d taken together. Funny ones he’d sent her from far away places, anniversary cards.

“I couldn’t throw them away,” he said. “But I couldn’t look at them either.”

Nina picked up one after the other to read the backs. Her mother’s handwriting, cheerful, full of small news from home.

“She loved you.”

“I loved her, too, and I love you.”

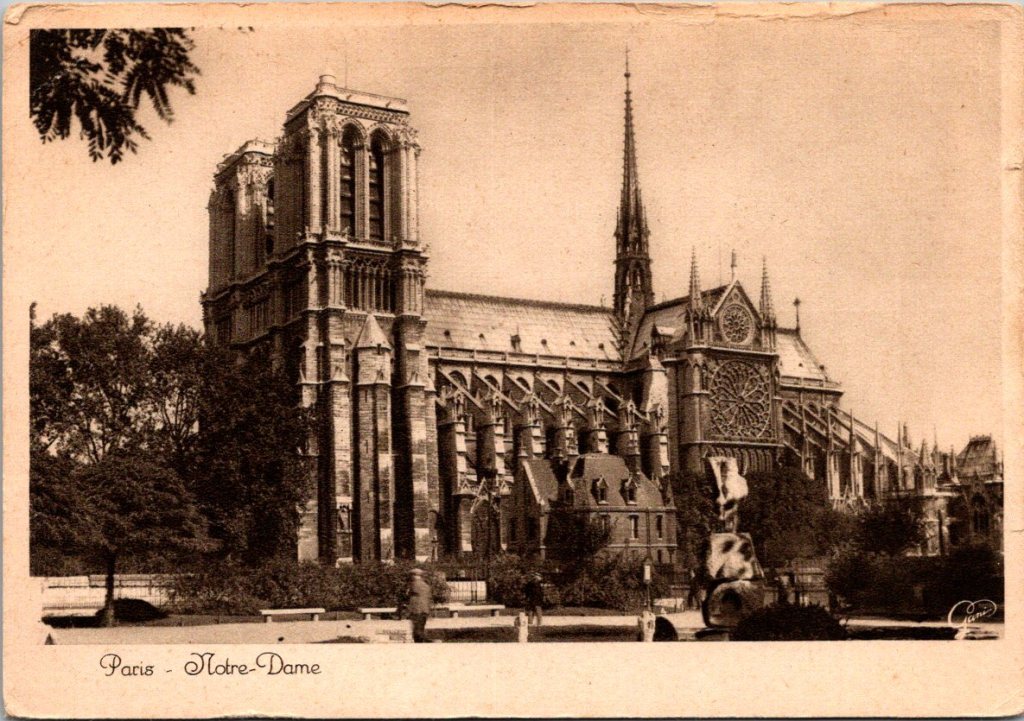

They sat with the postcards spread out between them, talking about travel and their family trips together. Tom unearthed the ones Nina herself sent home from the summer she spent in France. Both were careful to keep his collection from Delia separate from the ones Nina brought. They were both still sorting through the imperfect evidence of what had been.

“Next time,” Nina promised as she left. They hugged briefly, and she hopped in the car for the drive home on the freeway with the sunset to her right.

Monday, Nina found Mrs. Hanabusa in her usual spot, the late afternoon light turning everything gold.

“How was your visit?” Mrs. Hanabusa asked without looking up.

“Good. Hard. Both.”

“That’s how it goes.”

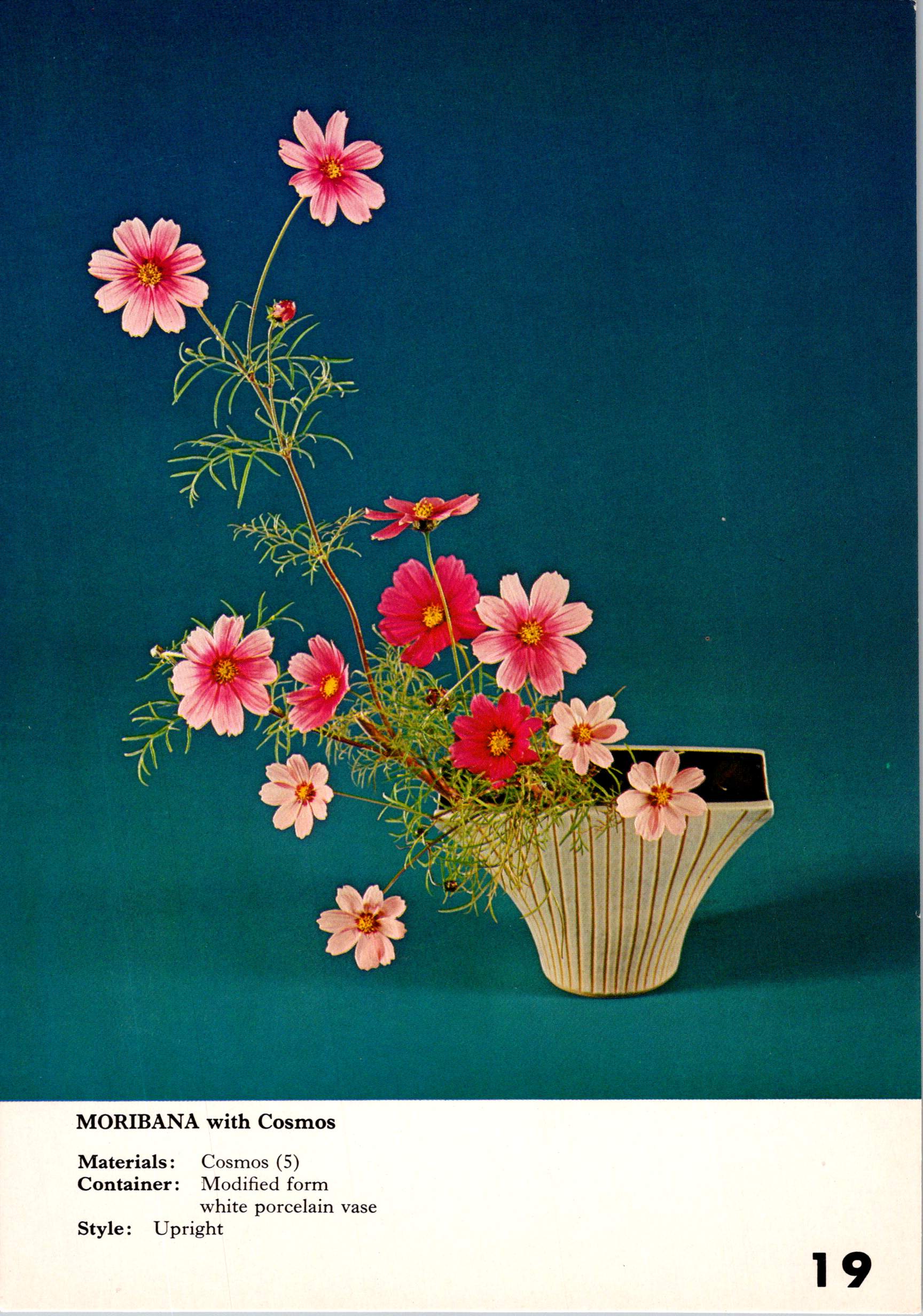

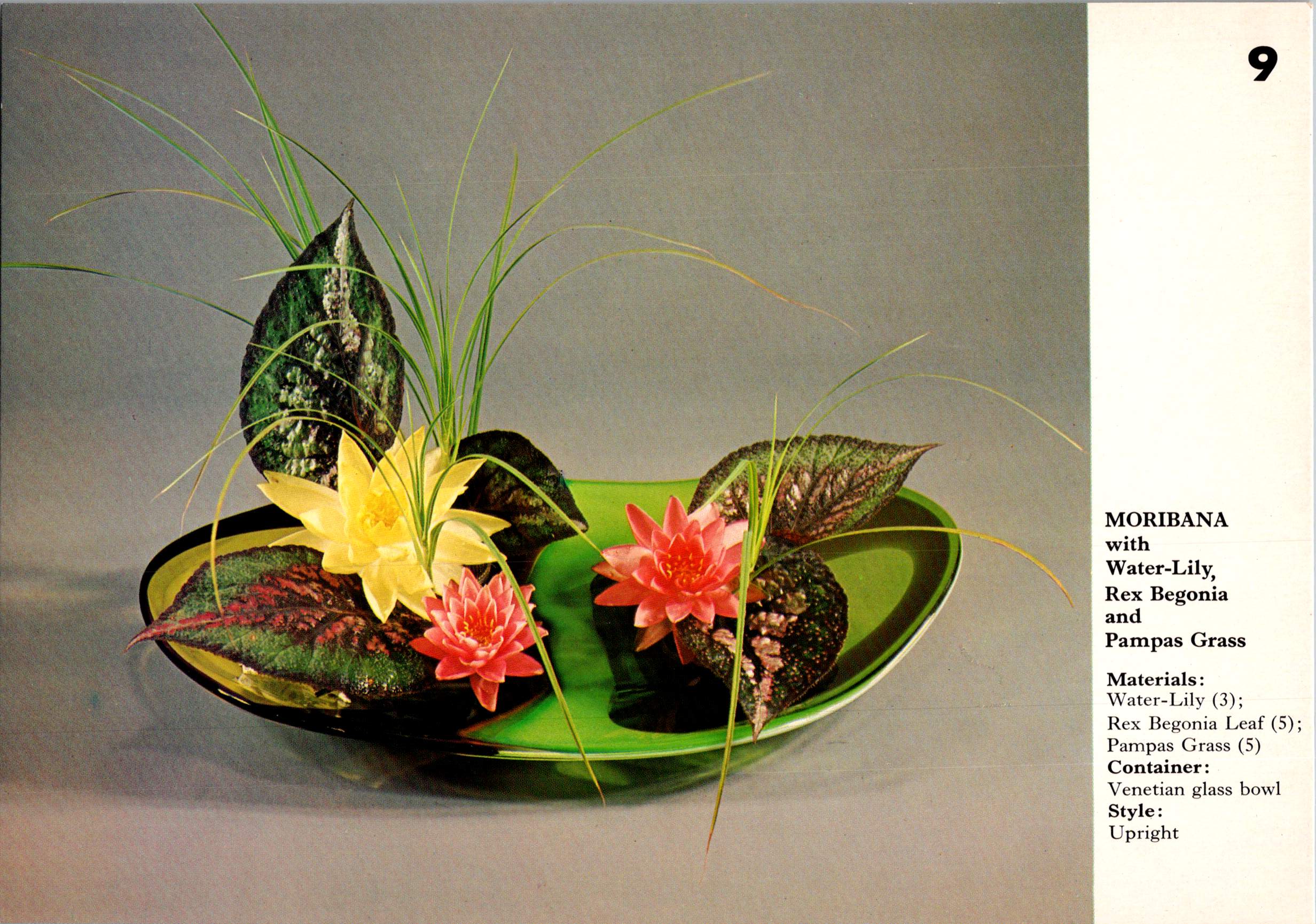

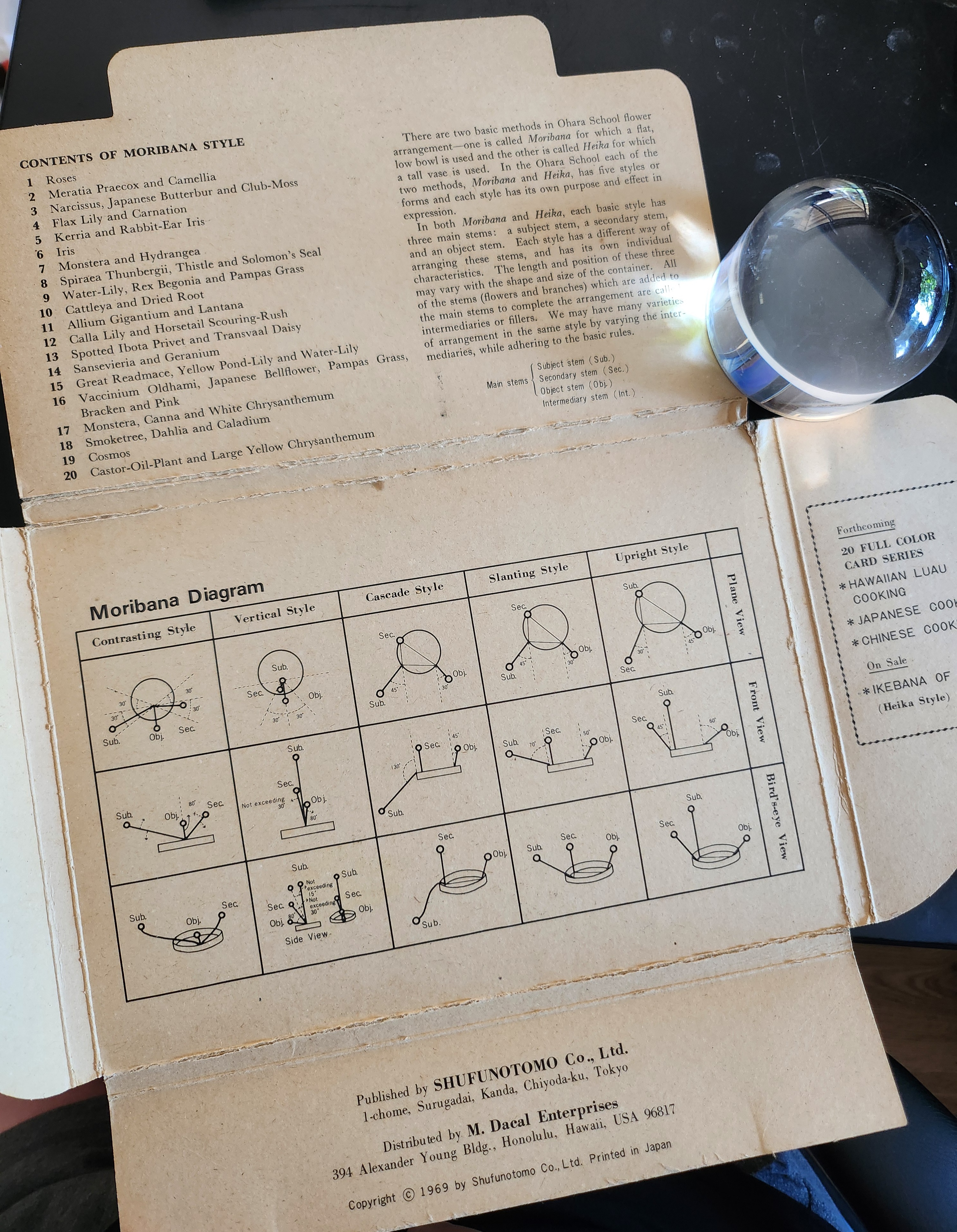

Nina found herself marveling, again. Mrs. H’s daily practices, the flower arranging, carefully selecting which sentiments to include and which to set aside. She seemed to belong more to the glow than the room, now.

“How did you learn to be at peace in the world?”

Mrs. Hanabusa smiled slightly. “Well, I needed it and then I experienced it once or twice. It felt good, and now I have practiced enough. Every day. Some days better than others.”

Peace wasn’t a state achieved once and held static forever. It was active, chosen, renewed daily through small deliberate gestures.

“You’re practicing, too, but you don’t call it that yet. It’s nicer when you know.”

Nina thought about the drive to Tempe, the decision to keep the postcards, the inclination to let her father try, and the fear he’ll fly away again. It was not easy, definitely practice. Also, yes… nice.

Nora’s cards came less frequently through the spring. Nina recognized the sacred cycle of becoming and belonging. Nora had less to say about longing, more about the daily goings-on. She was living in Taiwan.

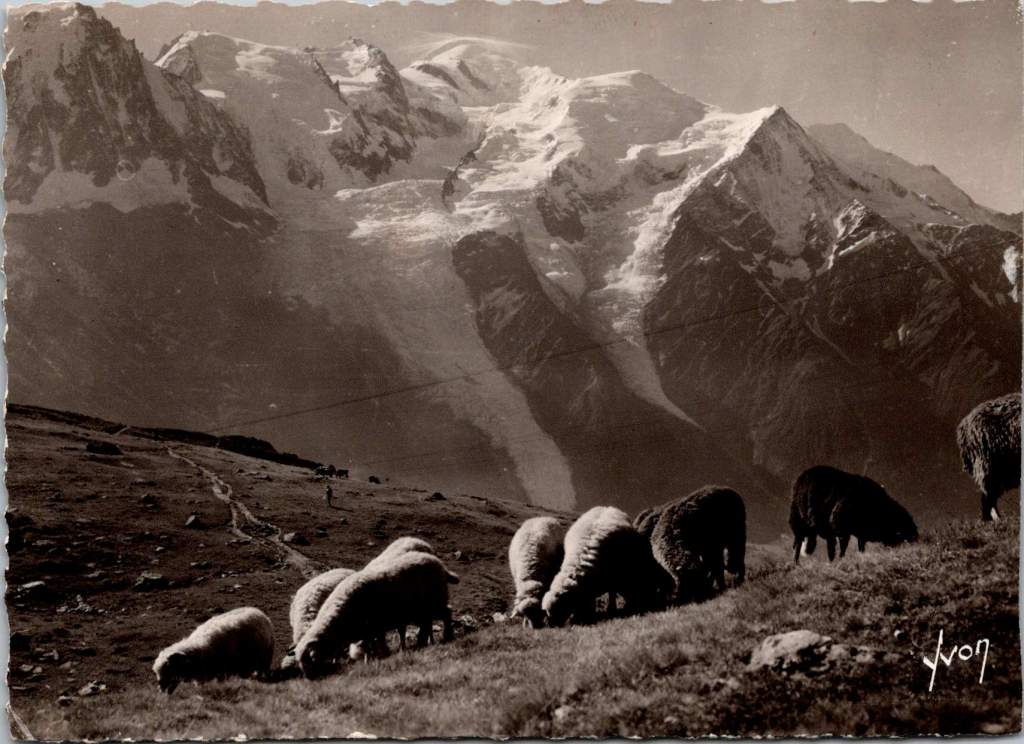

Hiked Taroko Gorge with work friends. Mountains are unreal—marble cliffs, jade rivers. Think of you, often. –N

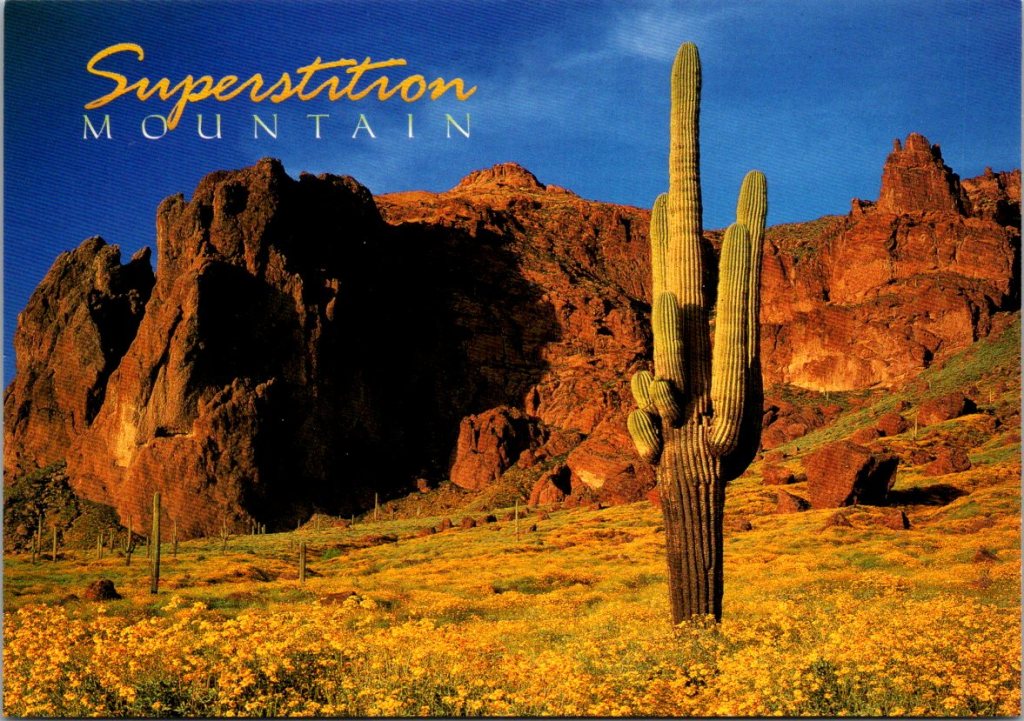

Nina pulled out a postcards of Saguaro at sunset awash with a super bloom of springtime flowers. She wrote her response, but didn’t rush it. Set it on her desk, next to the others ready to go out. There was time. Their lives would keep coming and going in a different rhythm now, and that was enough.

Though our holiday story series stops here, we hope you stay in touch!

Subscribe to get a message about a postcard every Wednesday.

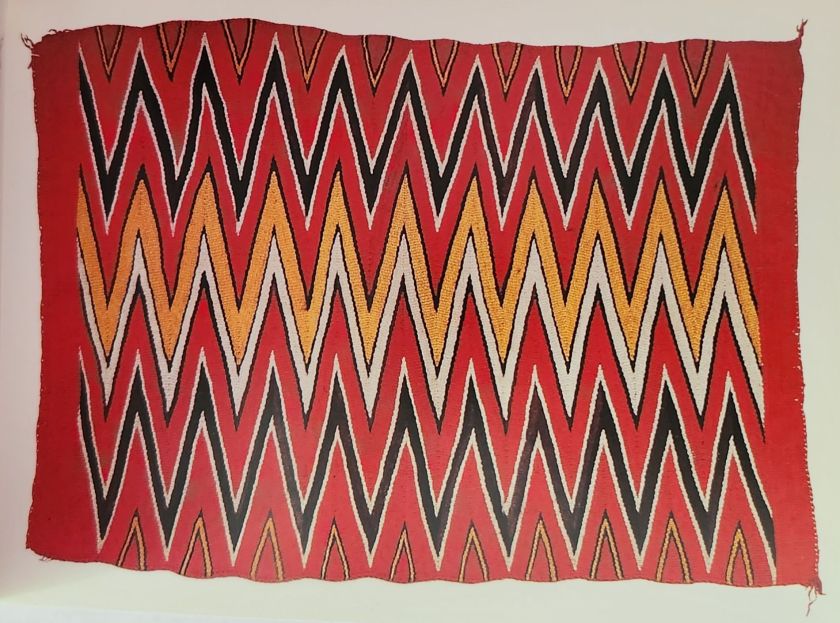

Also, love is in the air! Next month rare embroideries.