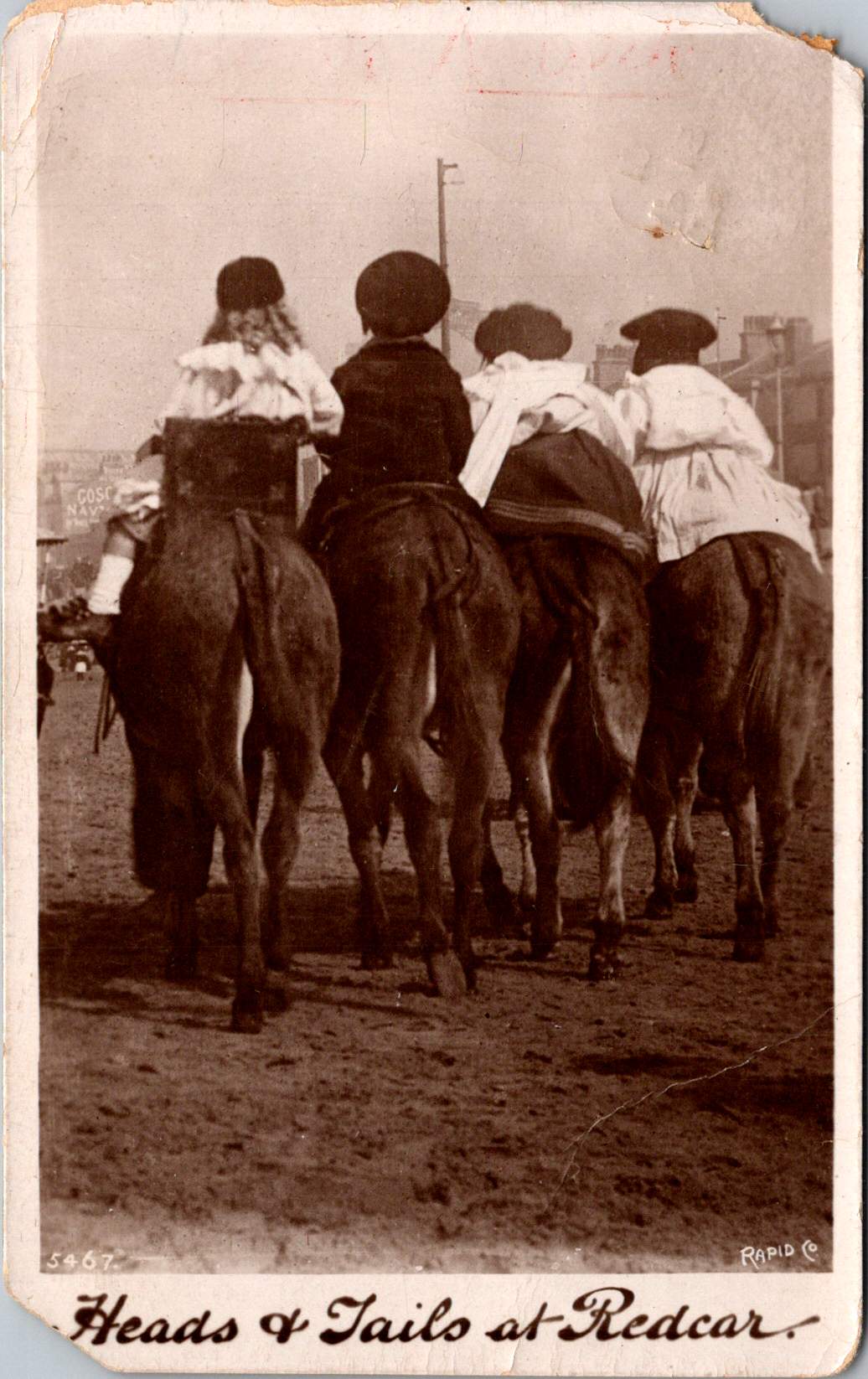

This real photo postcard with a memorable image bears the hand-scripted titled “Heads & Tails at Redcar.” One can still feel the April 18, 1910 embossed postmark on the card a century later. Addressed to Nurse Aird in Darlington from Redcar, the message is pragmatic.

Expect to arrive about 6.30 to-morrow evening. Love from Rennie

The seaside town of Redcar was transformed from a modest fishing village into a bustling resort town by the arrival of the railway in the mid-19th century, and became a beloved destination for working and middle-class families from throughout Britain’s industrial northeast.

In the 1910s, Redcar embodied the height of seaside grandeur. The impressive Coatham Hotel, built in 1871, dominated the seafront, its architecture expressing the optimism and ambition of the age. A pier stretched into the sea, its 1873 construction a testament to the engineering confidence of the era. Along the promenade, ornate gas lampposts cast their glow over evening strollers, while elaborate wooden shelters provided refuge from sudden showers.

The seafront architecture told a story of careful planning and civic pride. Victorian terraces, built of local sandstone or sturdy brick, were elegant facades looking at the sea. Behind them, a grid of streets housed seasonal workers, fishermen, and the growing permanent population drawn by the town’s prosperity. The Central Hall, opened in 1895, provided entertainment, while Methodist and Anglican churches with their reaching spires reminded visitors and residents alike of Victorian moral values.

Yet Redcar was never merely a tourist trap. The town’s proximity to mining linked it inextricably to Britain’s industrial might. The discovery of workable iron ore deposits in the Cleveland Hills in 1850 had sparked an industrial revolution in the region. By the 1910s, mines dotted the landscape, and the sight of industrial chimneys on the horizon reminded visitors of the region’s working heart. Many local people split their lives between seasonal tourist work and the demanding labor of the mines or ironworks.

This distinctive mixing of leisure and industry is part of Redcar’s character. Unlike some of Britain’s more exclusive seaside resorts, the community remained proudly connected to its working roots. The donkey rides captured in our postcard—a quintessential British seaside tradition—were an affordable pleasure for working families. The donkeys themselves, chosen for their gentle temperament and sturdy build, paralleled the town’s way: reliable, hardworking, and ready to provide joy to all comers.

On April 18, 1910, Rennie dashed off a quick note from Redcar to Nurse Aird, using one of Rapid Photo Company’s popular seaside postcards to announce a return to Darlington the following evening at 6:30pm. Such precise timing speaks to the reliability of the North Eastern Railway’s service between the coastal town and Darlington, where regular daily connections had become the lifeblood of the region.

The journey home would begin at Redcar’s Central Station, its Victorian architecture still relatively new and imposing in 1910. The late afternoon departure would catch the changing light over the North Sea, before the steam locomotive began its hour-long journey inland. As the train pulled through Middlesbrough and then west toward Darlington, the spring evening would be settling in, with the Cleveland Hills silhouetted against the dusk. Fellow passengers might have included ironworkers heading to night shifts, businessmen returning from coastal meetings, and perhaps other daytrippers who had enjoyed the seasonal pleasures of the seaside.

By evening, Rennie would step onto the platform at Darlington’s Bank Top station, the time at the coast already feeling like a distant memory. Perhaps a deliberate choice of train, selected to arrive after Nurse Aird’s duties were complete or to catch the end of visiting hours. Whatever prompted the journey, the postcard captures the easy mobility that the railway enabled, allowing residents of these northeastern towns to move between coast and country with a regularity that would have seemed remarkable just a generation earlier.

The subsequent century would bring profound changes to Redcar. The pier, once a symbol of Victorian confidence, fell victim to storm damage and was demolished in 1981. The grand Central Hall disappeared. Many Victorian hotels were converted or demolished as tourism patterns changed. Most significantly, the industrial base that had provided much of the region’s wealth underwent dramatic transformation. The 2015 closure of the SSI steelworks marked the end of an era, dealing a devastating blow to the community.

Modern Redcar presents a complex picture of a community in transition. The Redcar Beacon opend in 2013 (locally dubbed the “Vertical Pier”) reaches skyward, its contemporary design contrasting with the Victorian architecture that remains. Victorian terraces continue to face the sea, their sandstone facades weathered but dignified. The Clock Tower, dating from 1913, remains a local landmark. The town center struggles with empty shops, a challenge faced by many British high streets. The loss of heavy industry has forced difficult economic adjustments.

The community’s response to these challenges reveals much about Redcar’s character. The Palace Hub, housed in a former amusement arcade, provides space for local artists and craftspeople. Local groups organize beach cleaning and heritage walks, maintaining the town’s connection with its past while protecting its future. Locally run kitchens and groceries address modern challenges of food poverty while building community connections.

Most remarkably, the donkeys still plod along the beach in summer months. The same gentle animals that carried kids a century ago now delight a new generation of visitors. Modern care standards ensure rest periods, weight limits, and veterinary checks, but the essential experience remains unchanged. Children still laugh with surprise at their first encounter with these patient beasts, parents still snap photographs (will box cameras make another comeback?) and the donkeys still take their slow and careful steps, connecting past and present.

Redcar reminds us that progress isn’t linear and that community change involves deep dynamics of loss and renewal. The town that grew wealthy on iron ore and Victorian tourism now seeks new paths forward in renewable energy and cultural heritage. What has remained is both quirky and reliable: a donkey ride on the beach on a summer’s day.

While the grand Victorian hotels and ore industries of the region have largely passed into history, the humble donkey ride endures. Sometimes the most modest traditions prove the most durable, and the true character of a place resides not only in grand achievements but also in simple, timeless pleasures.

Who indeed would have guessed that of all Redcar’s attractions, it would be the donkey rides we couldn’t live without? Perhaps it is fitting that these patient animals, who witnessed the town’s rise, decline, and ongoing reinvention, continue to reliably entertain (and endure) new generations.