Tom’s rental car idled at a red light on University, three blocks from his apartment. He’d made it through Sky Harbor quickly, drove straight here without stopping for groceries or coffee or errands. Just land and figure out what’s next, he thought.

The apartment was small, on the second floor of a stucco complex built in the eighties. View of the parking lot. He’d signed the lease abruptly after Delia died. Left the house for Nina to handle. Since then—hotel rooms in Atlanta, crew bunks in Singapore, a fishing boat off Catalina.

He parked, climbed the stairs, unlocked the door to recycled air and silence, flipped through the mail piled on the counter from the last time he was here. He missed the last local election. There was a party in a park nearby. A local group is replacing trees that were damaged in the last freak storm.

He set his bag down, pulled out his phone, texted Nina before he could reconsider.

I’m in Tempe. Can we meet? That coffee shop you like?

Three dots appeared. Disappeared. Appeared again.

Yup, be up there tomorrow. 10am.

Tom exhaled. Opened the refrigerator, stared at nothing for a moment, and closed it. He sat on the couch, looked at the unpacked boxes, looked at the random furniture. Looked at his hands, and thought, tomorrow. Then he grabbed his keys to run out for a beer and a burrito.

At the coffee shop, Tom arrived early, ordered coffee he didn’t drink, watched the door. Nina came in exactly at ten. Saw him, hesitated, turned toward the line, but walked over to her dad instead.

“Hi.”

“Hi.”

Nina set her keys on the table and went to get her drink. A few minutes to breathe and focus while she waited in line. He was actually here. Wow.

Back at the table, Tom tried to start, stopped, and started again. Exasperated, he whispered a groan. “How do people do this?”

“Well, you always asked Mom.”

“Truth,” he conceded. “I keep getting on planes. Keep going up. Can’t figure out how to stay down.”

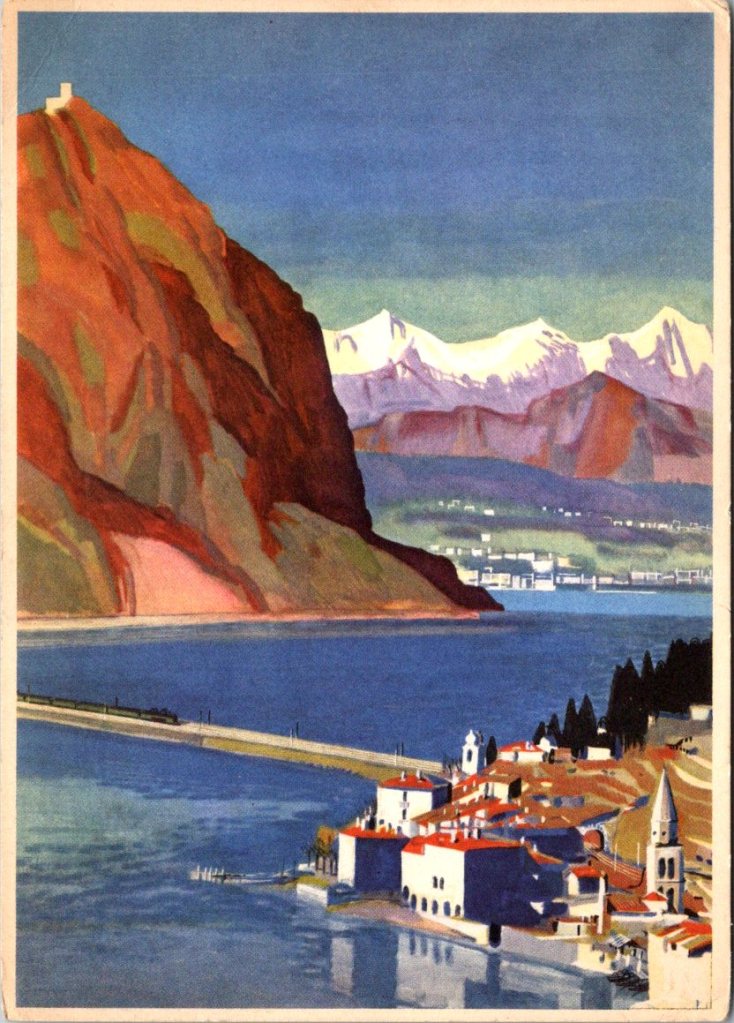

Nina’s face was careful, neutral. “I know. You send postcards.”

“Lonely postcards.”

“I like them.” She paused, a little surprised herself.

“This woman I know at work told me about her father. He came back from the internment camps different. Couldn’t talk about what he’d lost. Just went quiet. Disappeared into himself even when he was sitting right there.”

Tom blinked at her, stunned by the comparison. “I’m not—”

“I know you’re not. But you get away from a lot up there.”

Tom set his coffee down. “Look… I’m trying… to be present… more.”

“Okay.” Nina’s hands tightened around her cup.

“Let me know when you’re back, next,” she said slowly. “We could meet at your place. Maybe make it feel like home.”

“Sure. that’s good. It doesn’t feel like anything right now.”

They finished their coffee, scooted out of the booth, and hugged. Nina picked up her keys.

Tom drove back to the apartment. Stood in the doorway looking at the accumulation of a life he’d been avoiding.

He started with the kitchen. Unpacked Delia’s dishes, the set they’d used for at least thirty years. Put them in the cabinets. Drove to the grocery store, bought coffee and bread and eggs. Real food that would probably rot. Fine, that might actually be normal. Small steps. He’d try again tomorrow.

The knock came mid-morning. George opened the door to find Lily holding a canvas bag, Mai standing behind her with a patient smile.

Lily marched into the foyer, serious. “I brought MY paints.”

“She wanted to paint, here, with you,” Mai said.

“CATS! We want to paint cats,” she announced.

“Well then.” George stepped aside. “Come in.”

They set up at the kitchen table—Jennie’s old watercolor set now showing signs of use again. Lily arranged her brushes with care, filled a bowl with water, selected paper from the pad.

“Could you get the big book, Grandpa?” Lily asked.

George knew exactly the one she wanted. Large and heavy, and art book with full color illustrations. Yes, cats, and many more species with great examples of all variety to try one’s hand.

George pulled his chair to face the window. Lily pulled hers beside his. They worked together, silently, side by side. Lily’s brush moved in quick confident patterns. Bold strokes, loose shapes that captured moments more than detail.

George surprised himself by drawing with a sharp graphite pencil. His hands remembered motions he hadn’t used in years. Careful lines, patient shading, the disciplined attention that both he and Jennie loved.

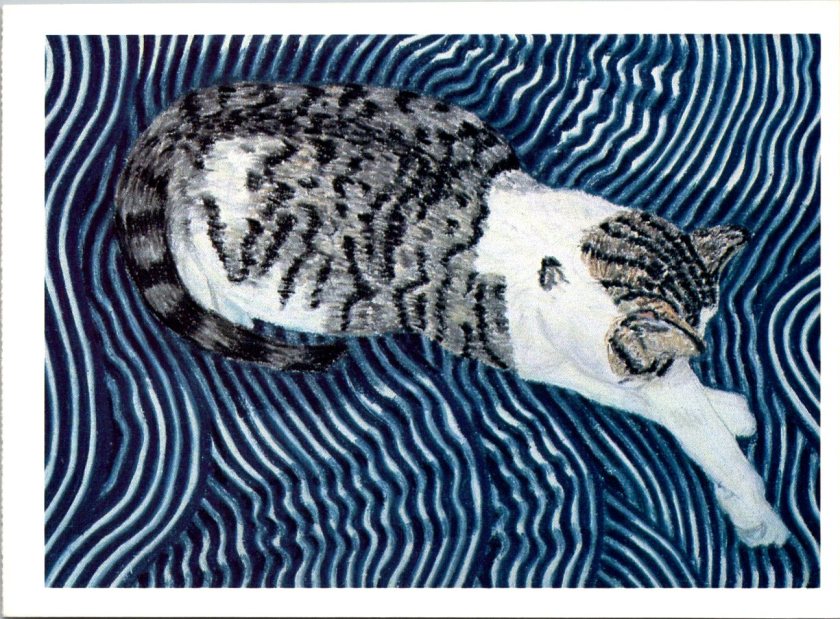

Lily finished first. Held up her painting. “It’s not exactly right.”

“Tell me more…”

“The shape isn’t right. The lines don’t add up. It doesn’t look like a real cat.”

“Artists see differently than scientists,” George said. “Scientists measure. Artists feel. Both ways matter. Your colors are very bold.”

Lily considered this. Looked at his drawing, and said confident,”Yours is the scientist way.”

“Can I keep yours?”

“If I can keep yours.”

“Deal.”

Mai came back an hour later. Lily packed her supplies, carefully laying her paintings on the countertop to dry. At the door, she hugged George—quick, unselfconscious, generous.

After they left, George found a frame in the closet and mounted the entirely impossible animal—calm, loose, joyful. Hung it where he’d see it every morning.

The postcard arrived in Tucson ten days after Nora mailed it. Nina turned it over. Nora’s handwriting, smaller now, more compact.

Lunar New Year, red lanterns everywhere. The city transforms—fireworks, night markets, families. The work is good, the project is extending. Solitude still a gift.—N

Nina read it twice. Carried it inside. Pinned it to her wall beside the others. Seven postcards now, creating their own pattern. Different textiles, different messages, her same friend after all this time. She pulled out her phone, typed a response.

Got your latest. Glad you’re staying. Take your time.