The teahouse was tucked next to a dumpling shop on a narrow lane in Da’an District. Nora walked past it three times before noticing the English sign: Tea by Appointment Only.

Inside, a woman near seventy arranged porcelain cups on a low table. She glanced up, assessed Nora with a single look, and gestured to the cushion.

“First time?”

“First time for tea ceremony,” Nora said. “Not first time feeling lost.”

The woman smiled. Poured water over the leaves. The scent rose—something green and grassy, nothing like the black tea Nora’s grandmother used to brew.

“Lost is good,” the woman said. “A reason to pay attention.”

Nora’s colleague Mei-Ling had taken pity after watching Nora eat lunch alone for the third week running. “You need to get out,” Mei-Ling had said. “Explore. Be alone in a place that’s not your apartment.”

So here she was. Alone. Not lonely.

Her phone buzzed. A text from Nina. Nora silenced it without reading.

The tea was bitter, then sweet. She drank slowly.

“You travel alone?” the woman asked.

“Always.”

Nora had spent years cultivating solitude—long drives through Arizona backcountry, dawn hikes in Sabino Canyon, evenings on her balcony with no one talking. She chose the Taipei assignment partly for the chance to be anonymous and untethered.

The woman poured another cup. “Tourists look for what they expect to see. Solo travelers find who is actually there, including themselves.”

Nora thought about the next postcard to Nina. She wanted to tell her about the teahouse, the silence, the strange comfort of being somewhere no one knew her name.

It’s lovely to be solo in a strange land. Watching without explaining. Moving without negotiating. I sometimes forget who I am at home.

She finished her tea, bowed to the woman, stepped back into the crowded street feeling lighter than she had in months.

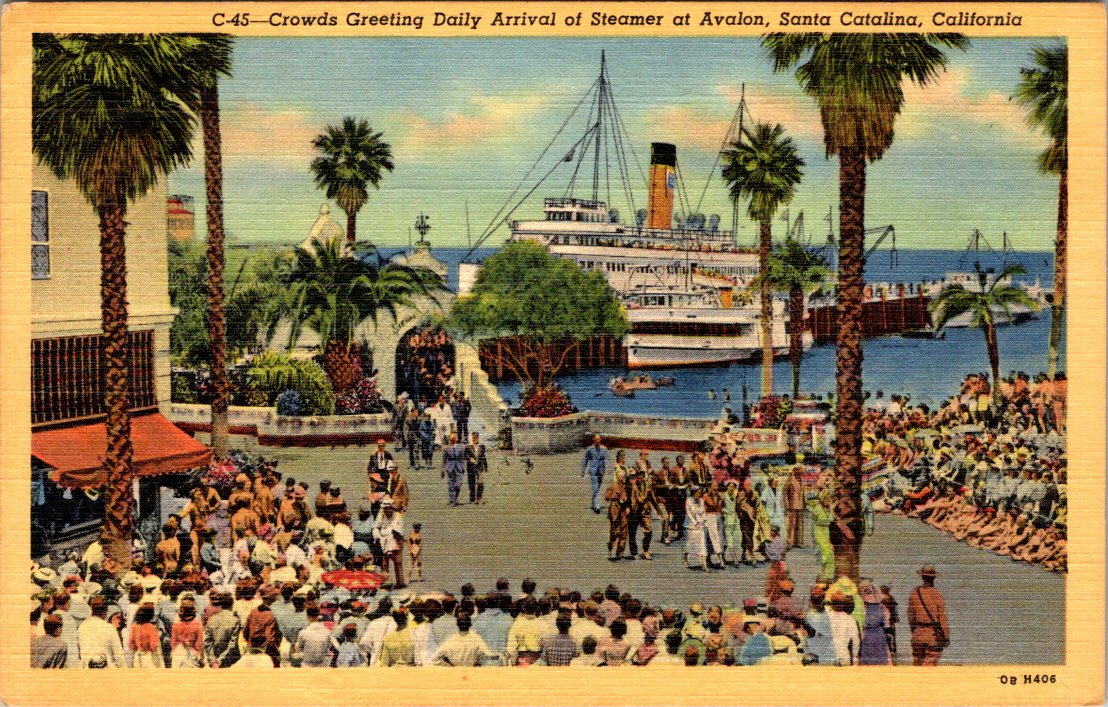

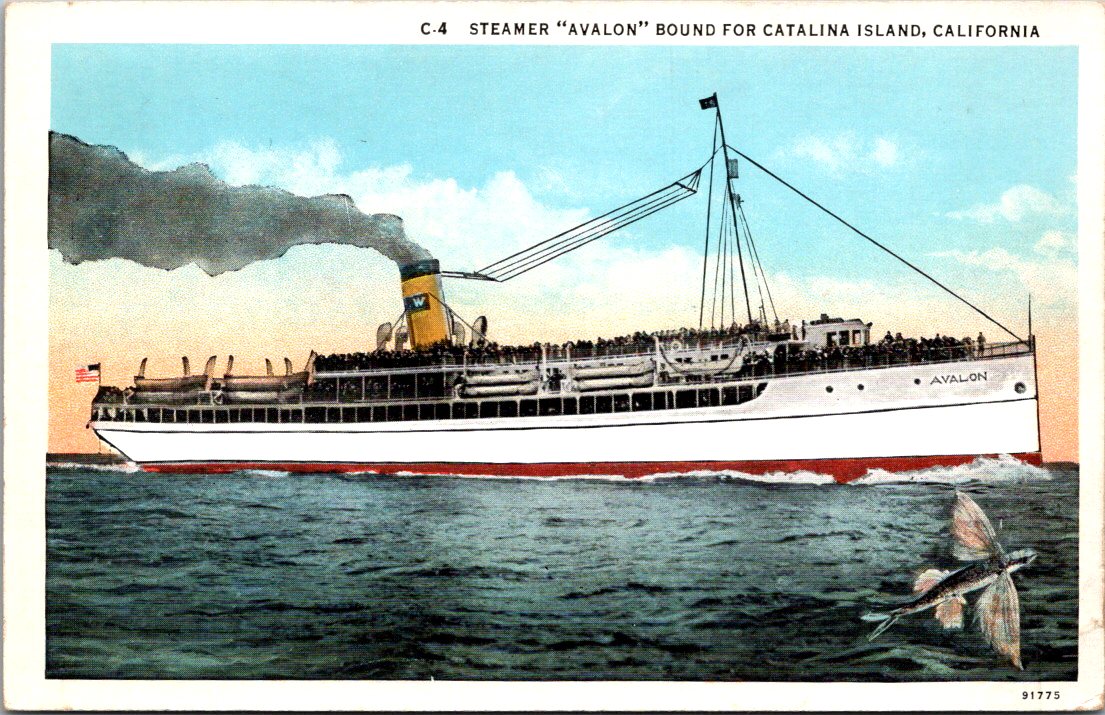

Tom stood on the deck of a fishing charter near Catalina, watching the captain clean yellowtail in the afternoon sun. He worked the knife along the spine with practiced efficiency, lifting the skin and scattering ribbons of bronze scales across the wet deck.

Tom was at sea three days, paid in full. His time between flights was long enough, he could have gone to Phoenix to check on the empty apartment. Or driven the two hours to Tucson to talk to Nina. Instead, he’d gone straight from the airport to the marina.

The ocean felt safer to Tom. He knew what he was dealing with—wind, current, the pull of the moon. On land, everything felt unmoored and awash in silence. The apartment with no one else there. Nina’s careful, measured heartache. The desperate life he’d abandoned in favor of flight schedules and hotel rooms.

The captain looked up. “You alright, man?”

“Fine.”

“You don’t look fine. You thinking about jumping?”

Tom laughed, the gallows humor helped. “Not far enough down.”

The captain went back to his work. Tom watched the horizon. His daughter was not far away. Working at the hospice. Taking care of people the way she’d taken care of her mother. While he was gone somewhere over the Pacific.

Tom didn’t make it to Jennie’s funeral. Delia was still sick and he had a flight schedule to keep. George hadn’t said much.

When Delia died two months later, George drove from Minnesota. Stayed ten days. Made coffee, answered the phone, helped with plans, and stood beside Tom at the service. Then, George drove back alone. Tom couldn’t make himself useful like that to anybody. Couldn’t even make himself stay.

A raven landed on the railing, tilted its head.

“Where’d you come from?” Tom asked.

The raven looked at Tom, croaked once, deep in its throat.

Suddenly the words came to him. He didn’t have a pen or a postcard handy, but finally he had something to say.

Flying solo is for the birds.

The raven lifted off, circled once, flew toward shore. Tom watched until it disappeared, then looked at his phone. He could get out of LA tonight, and rework his schedule from Phoenix next week. Enough time to get to Tucson and back, and to try.

The envelope arrived among the usual stack. Tom’s cramped handwriting unmistakable on the address. George carried it inside, set it on the kitchen table, made coffee before opening it.

Inside, a single sheet torn from a legal pad, Tom’s words filling margin to margin. George read it twice.

George—

Sorry it’s been so long. Don’t know how to say what needs to get out.Been working more flights than I should. Phoenix to anywhere. Hotel rooms are easier. Nina barely talks to me. Can’t blame her.

You drove all the way to Delia’s funeral. Made everything possible. I should’ve done the same for you and Jennie. Told myself it was work. We both know better. You’ve always been better at this life.

I’m sorry. Thank you. Stay warm, and let’s talk soon.

—Tom

Tom was a restless kid — climbing trees, running off, coming home with scraped knees. George stayed close, watched birds, kept track of his brother.

After Jennie died, Tom just wasn’t around. George wanted to be angry but didn’t have the strength. Grief made him numb for awhile. Now, he was just glad to have his brother back, or at least a longer letter.

Mrs. Hanabusa sat by her window in the common room, as she often did. Hands folded in her lap. Face turned toward the light. Eyes resting gently on the flowering hibiscus outside.

Nina paused in the hallway, watching.

How did she keep such a calm reserve? After the camps, after losing everything, seeing your family degraded. How did she maintain that peace?

She would probably credit her mother, her grandmothers, and their extended friends and family. All gone, except her sister. How does she do it, still?

Mrs. Hanabusa turned her head slightly and smiled.

Nina smiled back, and walked on.

The story above is fiction, but the new Postcard People feature is real life! Meet Christine N. from Switzerland, who posts about her grandmother’s collection.

Discover more from The Posted Past

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.