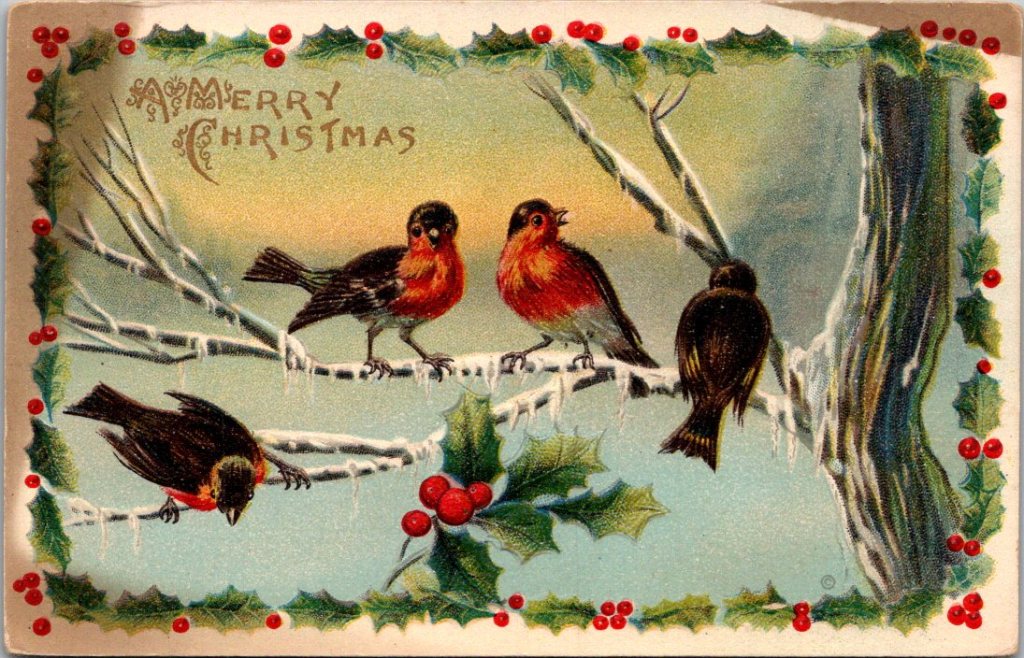

George’s daughter called on Tuesday evening. “The kids loved the postcards, Dad. Emma especially. She wants to start birding… with you.”

George felt a dial turn in his chest. “She does?”

“She’s been asking about your old field guide. The one you used to carry.”

After they hung up, George went right to the closet. Found the guide on a high shelf, spine cracked, pages marked with decades of pencil notes. He’d bought it in 1978. Carried it on weekend drives, on fishing trips, on the slow walks he took with each kid as they got adjusted.

He wiped dust from the cover. Flipped through. His handwriting tracked sightings—dates, locations, weather. A life measured in birds.

Emma would need binoculars, too. His old pair hung on a nail in the garage. He loved these trusty old binos. It would be hard to give them up. Maybe he should buy her a new pair? But George imagined seeing Emma out on the trail in front of him, patiently observing and tracking it all, just as Mai had. It was worth the heartache.

Lily needed art supplies—he remembered Jennie’s watercolor set, still good, stored in the craft closet. Paints and brushes. Clean paper. Save the easel and the satchel for next time.

Always books for Jack, but it was a hard choice. George searched his shelves. He found volumes he’d loved, but they were too intense for Jack right now. Shy and studious, he might like America, Land of Beauty and Splendor, a Reader’s Digest hardback with a handsome leather spine. Good chance he’d help Emma plan her birding trips with it.

By evening, the kitchen table was covered with brown paper and string. Three packages taking shape. The field guide and binoculars for Emma. The watercolor supplies for Lily. A stack of books for Jack.

George wrapped slowly, carefully. He wrote notes and tucked an old Christmas postcard in each one. He’d never been good at gifts. Always second-guessed himself. But these felt right. Things that had mattered to him, passed down. Things they’d actually use. He whispered to himself, “Old is still good.”

Christmas Eve morning, George loaded the packages into his truck. The drive to Wabasha took twenty minutes. The sky was gray, threatening snow.

Mai opened the door, flour on her hands. “Dad! Come in, it’s freezing.”

“Just wanted to drop these off.” George carried the packages inside, set them under the tree.

Emma appeared from the hallway. “Grandpa!”

Jack and Lily followed, voices overlapping. George let himself be pulled into the warm house, the noise, the aromas coming from the oven.

George didn’t look a thing like Santa—tall and thin, no beard, flannel shirt instead of red suit. But standing there with his grandchildren around him, he felt jolly. This was better than he’d imagined. Better than the quiet house and the empty days, anyway. Being a grandfather mattered more than anything now.

“Can we open them?” Lily asked.

“Christmas morning,” Mai said. “Dad, stay for coffee?”

George stayed for an hour. Drank coffee. Watched the kids. Drove home through the light snow feeling content, maybe even peaceful.

Nina pulled the stack of stuff from her mailbox. Bills. A grocery store circular, and two postcards.

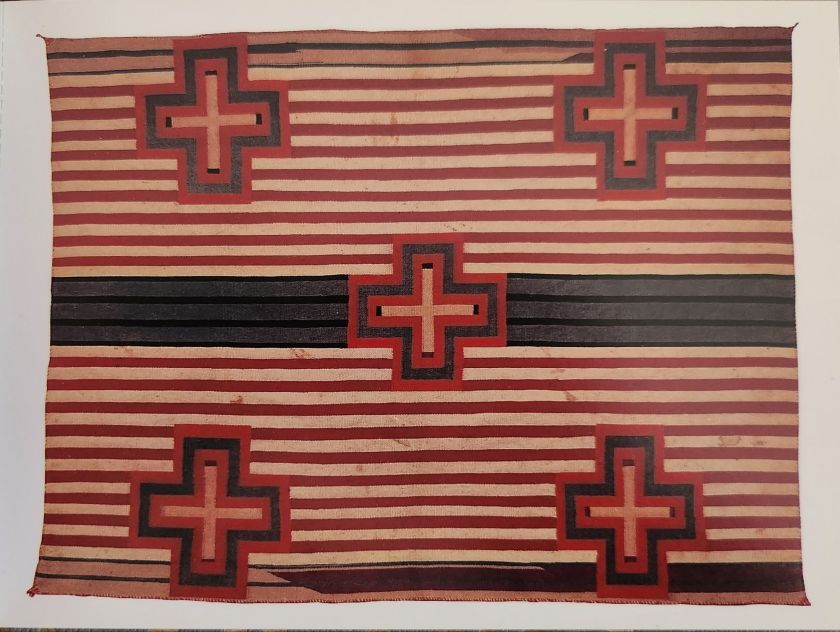

The first showed another Native textile—bold linear patterns in red, black, and cream with intense cross icons. Nora’s careful script on the back.

Hā lō. The words don’t come easily but people are kind. Cool and cloudy. I am floating in a haze between two languages and all the sights and sounds. —N

Nina flipped over the second card and took in a sharp breath. A generic Delta airplane photo. The handwriting slanted left, pressed hard into the faded card stock.

Layover. Thinking of you. -Dad

She hadn’t heard from her father in eight months. Not since he flew in for the funeral and left the next day.

Nina stood in the mailroom holding both cards. Nora’s textile and her father’s cardboard shrug. She whispered, “Merry Christmas, Dad,” and slipped them both into her bag.

Mrs. Hanabusa was by her window when Nina arrived for her shift. The older woman smiled. “You have mail.”

“How did you know?”

“The look you get.”

Nina pulled out Nora’s card. Showed her the textile pattern.

Mrs. Hanabusa took it carefully. Studied the bold lines, the sacred geometry. “Another one, but this is different, more dramatic.” She tilted it toward the light from outside and a mischievous grin washed across her calm visage. “My grandmother would have liked getting these back, too.”

Nina hesitated, then showed her the second card with the plane.

Mrs. Hanabusa looked at it, then at Nina, then waited.

“My father,” Nina said. “He’s a pilot. He sends almost the same card every time.”

Mrs. Hanabusa was quiet for another long moment. “My father came back from the camps different. Smaller and afraid. He couldn’t talk about what he’d lost. Some people need distance to be ok.” She paused. “But, that is not ok for you.”

“No,” Nina said. “It’s not.”

Nina looked at the card again. Thinking of you. Three words. A lifetime of absence compressed into a layover.

“I don’t know what to do with them,” she admitted.

“Keep it. Keep all of them, and figure out how to write back.”

Nina slipped both cards into her pocket. Nora’s textile and the latest of her father’s terminal attempts. Both efforts in their own ways, she had to agree.

Mrs. Hanabusa watched her. “These cards from your friend—they matter to me too, you know. Seeing which patterns she chooses next. What she wants you to know about her trip. That’s a kind of gift. Your friend is keeping her promise.”

“She said she’d send them all,” Nina said.

“Good,” Mrs. Hanabusa said. “You can show me each one.”

Time to Reconnect?

Though the story is fiction, a vintage postcard is still a great way to stay in touch. Browse our selection.

Discover more from The Posted Past

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.