With a closer look, this mysterious correspondence reveals the unique influence of its author on Adventist history and early 20th century approaches to wellness, nature, and medicine.

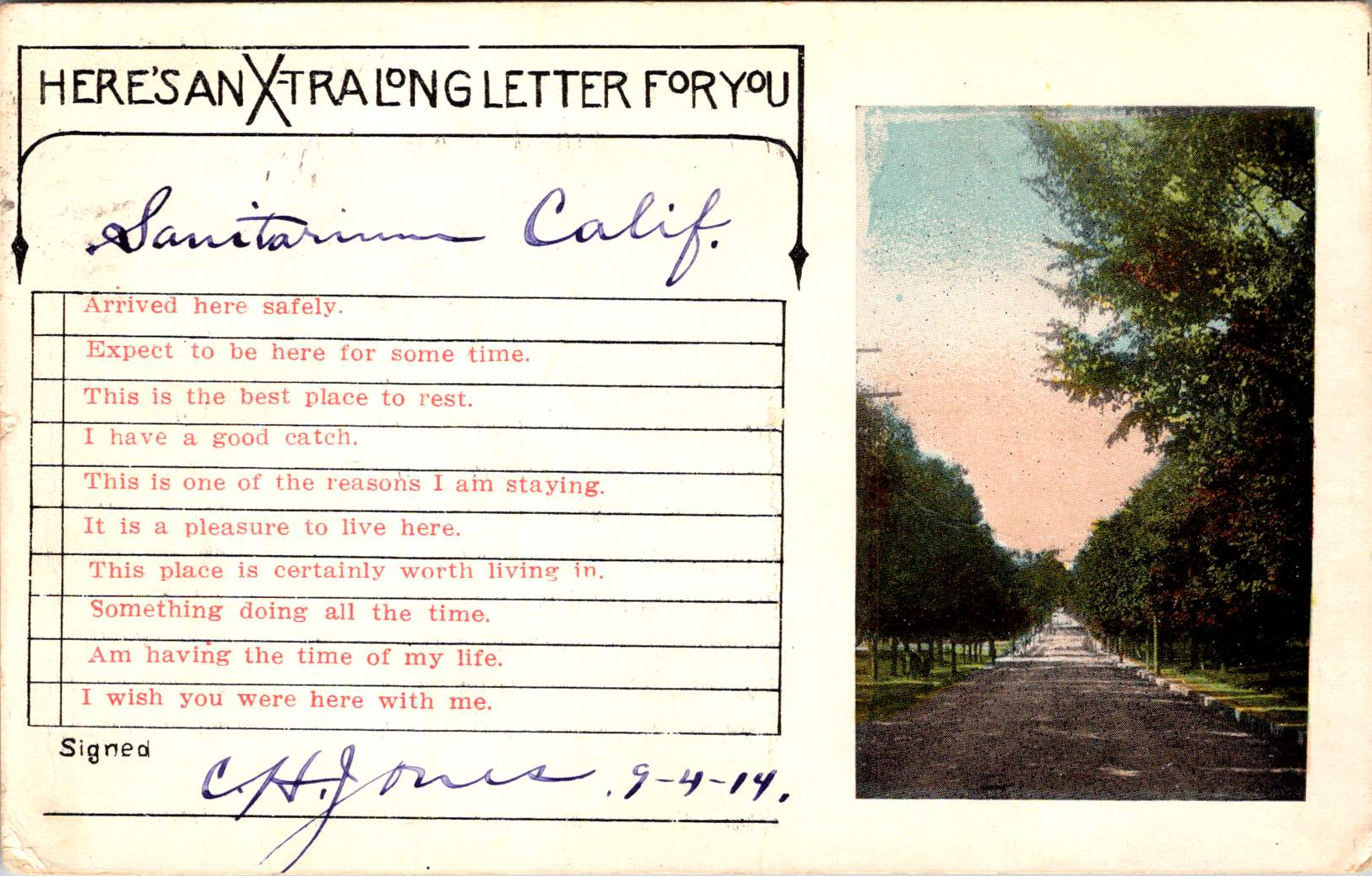

The front of the postcard offers a glimpse of the sanitarium’s picturesque surroundings. A color image shows a serene body of water flanked by lush greenery. Trees line the banks, their reflections shimmering on the water’s surface. In the distance, rolling hills rise, creating a sense of depth and showcasing the natural beauty of the Napa Valley. This image is accompanied by a pre-printed checklist of common sentiments a visitor might want to convey, such as “Arrived here safely” and “This is the best place to rest,” though Jones himself did not make a selection.

The words POST CARD are prominently displayed in green, capital letters across the back of the card with a divided section below. On the left, under the words “For Correspondence” appear five wavy blue lines drawn by hand, mysterious marks standing in for whatever personal message C.H. Jones might have penned to his wife. On the right side in the same elegant ink: “Mrs C.H. Jones, #305 Kenwood St., Glendale, Calif.” A green one-cent stamp featuring the profile of George Washington adorns the upper right corner, canceled by a postmark from Saint Helena, on Sep 5, 1914.

The St. Helena Sanitarium itself was a sight to behold. Nestled into the lush, forested hillside of the Napa Valley, the sanitarium complex was impressive and inviting. The main building, a grand structure of several stories with a white-painted exterior, stood out starkly against the dark green of the surrounding forest.

A series of covered verandas, visible on each level, offered patients and visitors alike the opportunity to take in the fresh air and stunning views of the valley. These outdoor spaces, so integral to the sanitarium’s health philosophy, wrapped around portions of the building, providing ample space for rest and contemplation.

The landscaping immediately surrounding the building was meticulous, with manicured lawns, ornamental shrubs, and small trees dotting the grounds. Palm trees hinted at the mild California climate. The entire complex exuded an air of tranquility and order, its gleaming white walls a beacon of health and hope set against the verdant backdrop of the Napa Valley.

The St. Helena Sanitarium played a significant role in both Adventist history and the broader health reform movement sweeping across America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This movement, driven by concerns about urbanization, industrialization, and changing diets, saw the rise of numerous health institutions known as sanitariums. These facilities, often located in picturesque natural settings, aimed to provide rest, rejuvenation, and health education to their patrons.

The most famous sanitarium was in Battle Creek, Michigan, led by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg. Kellogg, an Adventist physician, transformed the Western Health Reform Institute into a world-renowned health resort. The Battle Creek Sanitarium became a model for other such institutions, including St. Helena, with its emphasis on hydrotherapy, exercise, vegetarian diet, and the importance of fresh air and sunlight.

W.H. Kellogg, John’s brother, played a crucial role in developing health foods that became staples at the Battle Creek Sanitarium and beyond. The Kellogg brothers’ invention of corn flakes and other vegetarian foods aligned with the Adventist emphasis on a plant-based diet and had a lasting impact on American food culture.

The St. Helena Sanitarium, while smaller than Battle Creek, developed along similar lines. It was established in 1878 by a small group of Adventist believers who purchased the 10-acre Napa Valley property for $13,000. The initial facilities were modest, consisting of a small two-story building capable of accommodating about 40 patients. Dr. Merritt Kellogg, another brother of John Harvey Kellogg, was instrumental in its early development.

Like Battle Creek, St. Helena emphasized natural remedies and lifestyle changes. However, it had the added advantage of California’s mild climate and beautiful surroundings, which were seen as inherently health-promoting. The sanitarium quickly gained a reputation as a “Garden of Eden” for health seekers, attracting patients from across the country.

As the institution grew, it expanded its facilities and services. By the early 1900s, it had modern medical equipment, including X-ray machines and clinical laboratories, alongside its natural treatments. This blend of conventional and alternative therapies was characteristic of progressive sanitariums of the era.

The St. Helena Sanitarium also differed from Battle Creek in its continued close affiliation with the Seventh-day Adventist Church. While John Harvey Kellogg eventually separated from the church, St. Helena remained a central institution in Adventist health ministry. This was reinforced by Ellen G. White’s nearby residence at Elmshaven and her ongoing involvement in the sanitarium’s affairs.

By 1914, when C.H. Jones visited, the sanitarium had evolved significantly from its humble beginnings. Under the medical superintendence of Dr. George Thomason, who had been in charge since 1911, it had become a well-established medical institution, yet it remained true to its founding principles of natural healing and wholistic health.

The sanitarium’s mission was rooted in the Adventist health message, which emphasized prevention and natural remedies. Its philosophy, revolutionary for its time, promoted a holistic approach to health, treating the whole person – body, mind, and spirit. This was reflected in its services, which included hydrotherapy treatments, a vegetarian diet, exercise programs, and spiritual care.

One of the sanitarium’s key features was its use of natural springs on the property for hydrotherapy treatments. These water-based therapies were a cornerstone of the sanitarium’s approach to healing. The institution also boasted a nursing school, training professionals to carry the Adventist health message to other institutions and communities.

The sanitarium’s emphasis on health education extended beyond its walls. The Pacific Health Journal and Temperance Advocate, published by the “health retreat” at St. Helena, helped disseminate Adventist health principles to a wider audience.

The sanitarium’s reputation extended far beyond Adventist circles, attracting a diverse and often notable clientele. Among its reported visitors were William Jennings Bryan, the famous orator and three-time presidential candidate, and Jack London, the renowned author of “Call of the Wild.” Some sources even suggest that President Theodore Roosevelt may have visited, though this claim requires further verification. These high-profile guests, drawn by the sanitarium’s innovative treatments and serene environment, helped cement its status as a premier health institution.

Charles Harriman Jones, the sender of our postcard, was himself a significant figure in Adventist history. Born in 1850, he had dedicated his life to the publishing work of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. By 1914, he had been serving as the chief executive of the Pacific Press Publishing Association for over two decades, overseeing its growth and relocation from Oakland to Mountain View, California in 1904. His tireless efforts had helped establish the Press as a cornerstone of Adventist publishing.

Jones’ presence at the sanitarium is unsurprising given his close working relationship with Ellen G. White, who lived nearby at her Elmshaven home. White, a prolific author whose works were published by Pacific Press, took an active interest in the sanitarium’s affairs and often provided counsel on its operations. Her proximity allowed her to provide ongoing support, further cementing the institution’s importance within the Adventist framework.

While the St. Helena Sanitarium was thriving in 1914, the broader sanitarium movement was on the cusp of significant challenges. The early 20th century saw rapid advancements in medical science that would ultimately transform healthcare and challenge the sanitarium model.

The development of germ theory and its widespread acceptance in the medical community led to a greater emphasis on specific treatments for identified pathogens, rather than the natural remedies favored by sanitariums. The discovery of insulin in 1921 and the development of antibiotics in the 1930s and 1940s dramatically changed the treatment of many diseases, shifting focus away from the lifestyle and dietary approaches central to sanitarium care.

In the field of mental health, the rise of psychoanalysis and other forms of talk therapy began to challenge the sanitarium approach to treating nervous disorders. Sigmund Freud’s theories, gaining prominence in the early 1900s, offered new explanations for mental illness that went beyond the physical and environmental factors emphasized in sanitariums.

The standardization of medical education, following the influential Flexner Report of 1910, also played a role. This report led to more rigorous, science-based medical training and the closure of many schools that didn’t meet the new standards. As a result, newer generations of doctors were less likely to embrace the eclectic, nature-based approaches common in sanitariums.

The Great Depression of the 1930s dealt a significant blow to many sanitariums, as fewer people could afford extended stays at these facilities. World War II further accelerated the decline, as resources were diverted to the war effort and many sanitariums were converted into military hospitals.

By the 1950s and 1960s, many of the grand old sanitariums had closed or been converted into conventional hospitals or other facilities. The Battle Creek Sanitarium, once the flagship of the movement, closed its doors in 1957. However, some institutions, like the St. Helena Sanitarium, successfully transitioned into modern hospitals while retaining elements of their holistic health heritage.

The St. Helena Sanitarium, now known as Adventist Health St. Helena, stands as a testament to this evolution. While it has become a full-service hospital, it continues to emphasize whole-person care and lifestyle medicine, echoing its sanitarium roots. The continued operation of the St. Helena facility, albeit in a much-evolved form, speaks to the enduring value of some aspects of the sanitarium philosophy, even in an age of highly specialized modern medicine.

This 1914 postcard captures a moment just before the scientific and social changes that would reshape the medical landscape. At this late stage in his life, C.H. Jones would have seen firsthand the sanitarium’s significance and its role in promoting Adventist health principles but he may not have predicted the way medicine and healthcare would change. We can fill in the lines on the postcard to his wife with the details of a long career in Adventist publishing and health ministries, or perhaps more poignantly with the advice C.H. Jones would offer us today.

Discover more from The Posted Past

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.