In the mid-20th century, San Francisco stood as a beacon of the American West, a city of hills and fog, of cable cars and sourdough bread. It was a place where the Gold Rush era’s pioneering spirit met the post-war optimism of a nation on the rise. Tourism, conservation, and a changing cultural landscape were among the mix of motivations for depicting the city in these jumbo postcards. At the heart of these images was a man whose name has become synonymous with San Francisco photography: Gabriel Moulin.

Gabriel Moulin: The Studio Behind the Lens

Gabriel Moulin (1872-1945) was more than just a photographer; he was a visual historian of San Francisco. Born in San Jose, California, Moulin moved to San Francisco as a young man and established his photography studio in 1892. For over five decades, his keen eye and steady hand documented the city’s growth, its triumphs, and its tragedies.

Moulin’s career spanned a period of immense change in San Francisco. He witnessed and recorded the aftermath of the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire, capturing images that would become iconic representations of the city’s resilience. As San Francisco rebuilt and expanded, Moulin was there, his camera at the ready, to document the rising skyline and the engineering marvels that would come to define the city’s landscape.

One of Moulin’s most significant contributions was his documentation of major construction projects. His photographs of the Golden Gate Bridge and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, from their groundbreaking ceremonies to their final completion, provided a visual narrative of these monumental undertakings. These images not only served as historical records but also as symbols of American ingenuity and determination during the Great Depression era.

Moulin’s studio, located in the heart of San Francisco, became a hub for both commercial and artistic photography. While he was renowned for his architectural and landscape work, Moulin also excelled in portrait photography. His subjects ranged from everyday San Franciscans to visiting celebrities and dignitaries, creating a diverse portfolio that painted a comprehensive picture of the city’s social fabric.

The longevity and success of Moulin Studios spoke to the photographer’s skill and business acumen. Even after Gabriel’s death in 1945, his sons continued to operate the studio until 2000, maintaining the high standards set by their father. This continuity allowed the Moulin name to remain synonymous with quality San Francisco photography for over a century.

Today, the legacy of Gabriel Moulin lives on through the vast archive of his work. Over 500,000 negatives from Moulin Studios are now held by the San Francisco Public Library, a treasure trove of visual history that continues to provide insights into the city’s past. Researchers, historians, and photography enthusiasts alike pore over these images, each one a window into a moment in San Francisco’s rich history.

The Birth of the Jumbo Postcards

The set of jumbo postcards that we’re examining today represents a fascinating intersection of Moulin’s artistry, the booming post-war tourism industry, and the changing face of San Francisco. But how did these specific images come to be immortalized on oversized cardstock, ready to be sent across the country or tucked away as souvenirs?

The story likely begins in the late 1940s or early 1950s. World War II had ended, and America was entering a period of unprecedented prosperity. The rise of automobile culture and the expansion of the middle class meant more Americans than ever before were able to travel for leisure. San Francisco, with its iconic bridges, historic neighborhoods, and stunning natural beauty, was a prime destination for these new tourists.

Gabriel Moulin, or more likely his sons Irving and Raymond who were running the studio at this time, recognized the opportunity to capitalize on this tourism boom. They had a vast archive of high-quality images showcasing San Francisco’s most famous landmarks and neighborhoods. These images, some possibly dating back to Gabriel’s own work in the 1930s and 1940s, were perfect for reproduction as postcards.

Enter Smith’s News Company, a San Francisco-based publisher and distributor located on Ninth Street. Specializing in postcards and other printed materials, Smith’s News Company was well-positioned to turn Moulin’s photographs into sought-after souvenirs. The collaboration between Moulin Studios and Smith’s News Company was a natural fit – Moulin provided the artistic vision and photographic expertise, while Smith’s handled the printing, distribution, and sales.

The decision to produce these postcards in a “jumbo” 6×9 inch format was likely a strategic one. Larger than standard postcards, these jumbo versions allowed for more detail and visual impact, making them stand out in souvenir shops and newsstands. The bigger size also aligned with the grandiose, larger-than-life image that San Francisco sought to project to visitors.

The sepia tone of the postcards was another deliberate choice. Even if these images were taken in the 1940s or early 1950s, the sepia printing gave them a vintage feel, evoking a sense of history and timelessness. This aesthetic choice appealed to tourists’ desire for authentic, historical experiences, even as they engaged in modern travel.

San Francisco Through Moulin’s Lens

Let’s take a closer look at each of the images in this set of jumbo postcards, exploring what they reveal about San Francisco in the mid-20th century and how Moulin’s photographic style captured the essence of the city.

Chinatown: A Community in Transition

The image of Chinatown is perhaps the most intriguing of the set, offering a glimpse into the neighborhood’s complex social dynamics in the post-war period. The photograph was likely taken between 1946 and 1952, as evidenced by the styles of automobiles visible on the street.

In the foreground, we see a well-dressed Asian man, his dapper appearance speaking to the modernization and Americanization of the younger generation in Chinatown. Behind him, two men in military uniforms casually stroll in the opposite direction. This juxtaposition is rich with meaning, highlighting the multifaceted identity of Chinatown in the post-war era.

The presence of military personnel in Chinatown is significant. Following World War II, many Chinese Americans who had served in the U.S. military returned home with new skills, broader perspectives, and a strengthened sense of American identity. Their visible presence in the neighborhood symbolizes the increasing integration of Chinese Americans into mainstream society, a process accelerated by their wartime service.

The street itself is a vibrant scene of activity. Cars line the road, indicating the prosperity and mobility of the post-war period. The distinctive architecture of Chinatown is on full display, with pagoda-style roofs and Chinese signage creating a unique urban landscape. Lanterns hang across the street, likely in preparation for a festival or celebration, hinting at the community’s efforts to maintain cultural traditions.

This image captures Chinatown at a pivotal moment in its history. The repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 and the War Brides Act of 1945 had opened the doors to new immigrants, changing the demographic makeup of the community. The neighborhood was experiencing a population boom, with new arrivals from China joining established families and returning veterans.

The economic revival of the post-war years is evident in the bustling street scene. Many businesses in Chinatown were thriving, catering not only to the local community but increasingly to curious tourists drawn by the neighborhood’s exotic appeal. This tourism boom brought both opportunities and challenges, as the community navigated the commodification of their culture while striving to maintain authentic traditions.

Moulin’s composition of this photograph is masterful. By capturing both the traditional elements of Chinatown and signs of modernization and integration, he presents a nuanced view of the neighborhood. This image goes beyond the often stereotypical depictions of Chinatown common in tourist materials of the time, offering instead a glimpse of a dynamic community in the process of redefining itself in post-war America.

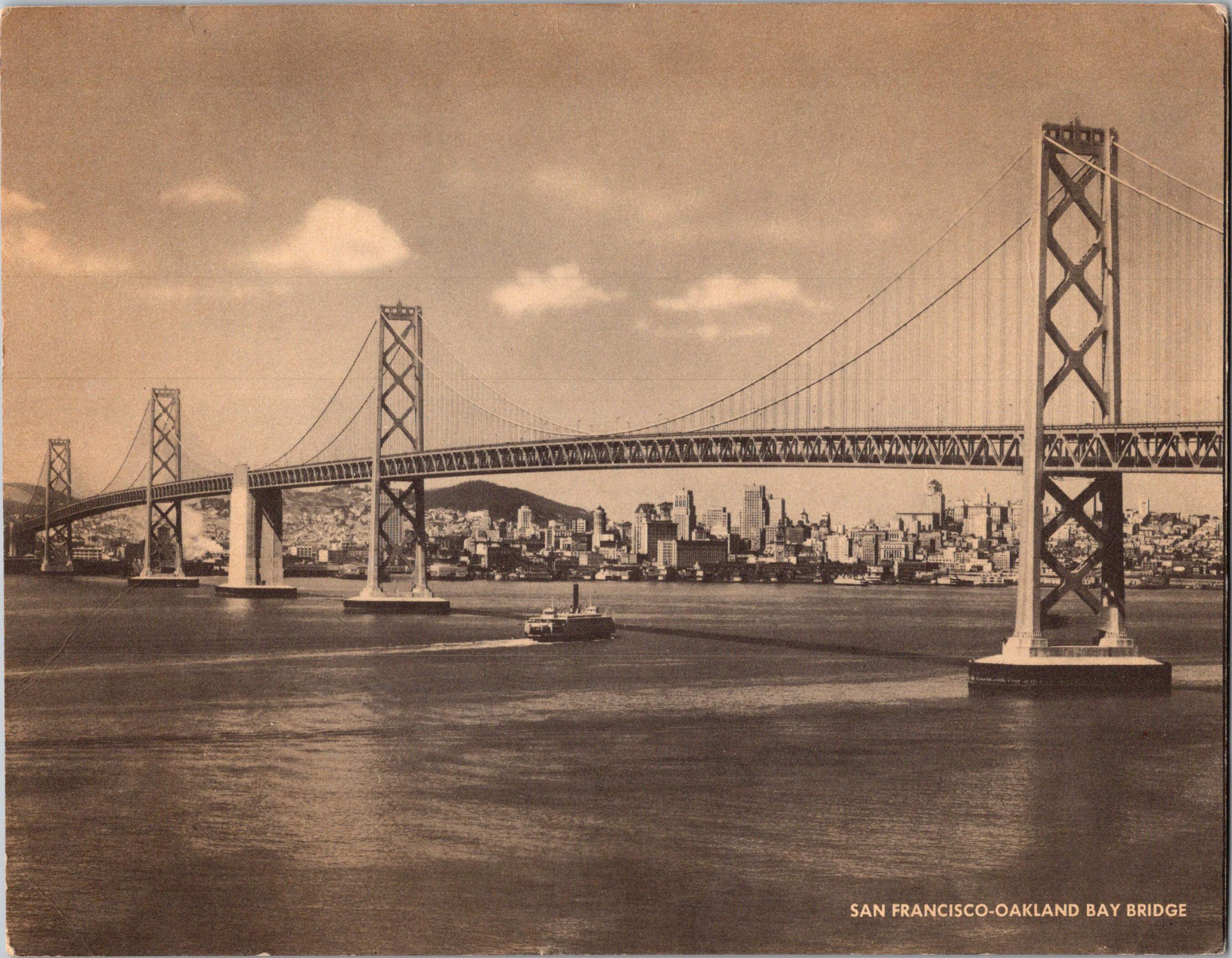

The Bay Bridge: A Symbol of Progress

The postcard featuring the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge showcases one of the engineering marvels that transformed the Bay Area in the 1930s. Completed in 1936, the bridge was still a relatively new and awe-inspiring structure when this photograph was likely taken in the 1940s or early 1950s.

Moulin’s composition emphasizes the bridge’s grandeur and its impact on the San Francisco skyline. The photograph is taken from a vantage point that captures the entire span of the bridge, with San Francisco’s growing downtown visible in the background. This perspective underscores the bridge’s role in connecting the East Bay to San Francisco, a link that was crucial for the region’s economic development and urban growth.

The image also captures a moment of tranquility on the bay. A small boat, possibly a ferry, can be seen in the foreground, a reminder of the bay’s maritime history and the transportation methods that the bridge had largely superseded. The calm waters and soft light create a sense of serenity, contrasting with the industrial strength of the bridge itself.

In the context of the post-war era, this image of the Bay Bridge represented more than just an architectural achievement. It symbolized American ingenuity, the ability to overcome natural obstacles, and the promise of progress. For tourists visiting San Francisco, the bridge was a must-see attraction, a physical manifestation of the city’s modernity and its crucial role in connecting the various communities of the Bay Area.

Moulin’s photograph, reproduced as a postcard, allowed visitors to take home a piece of this marvel. The image likely resonated with the optimism of the post-war years, when large-scale infrastructure projects were seen as key to America’s continued growth and prosperity.

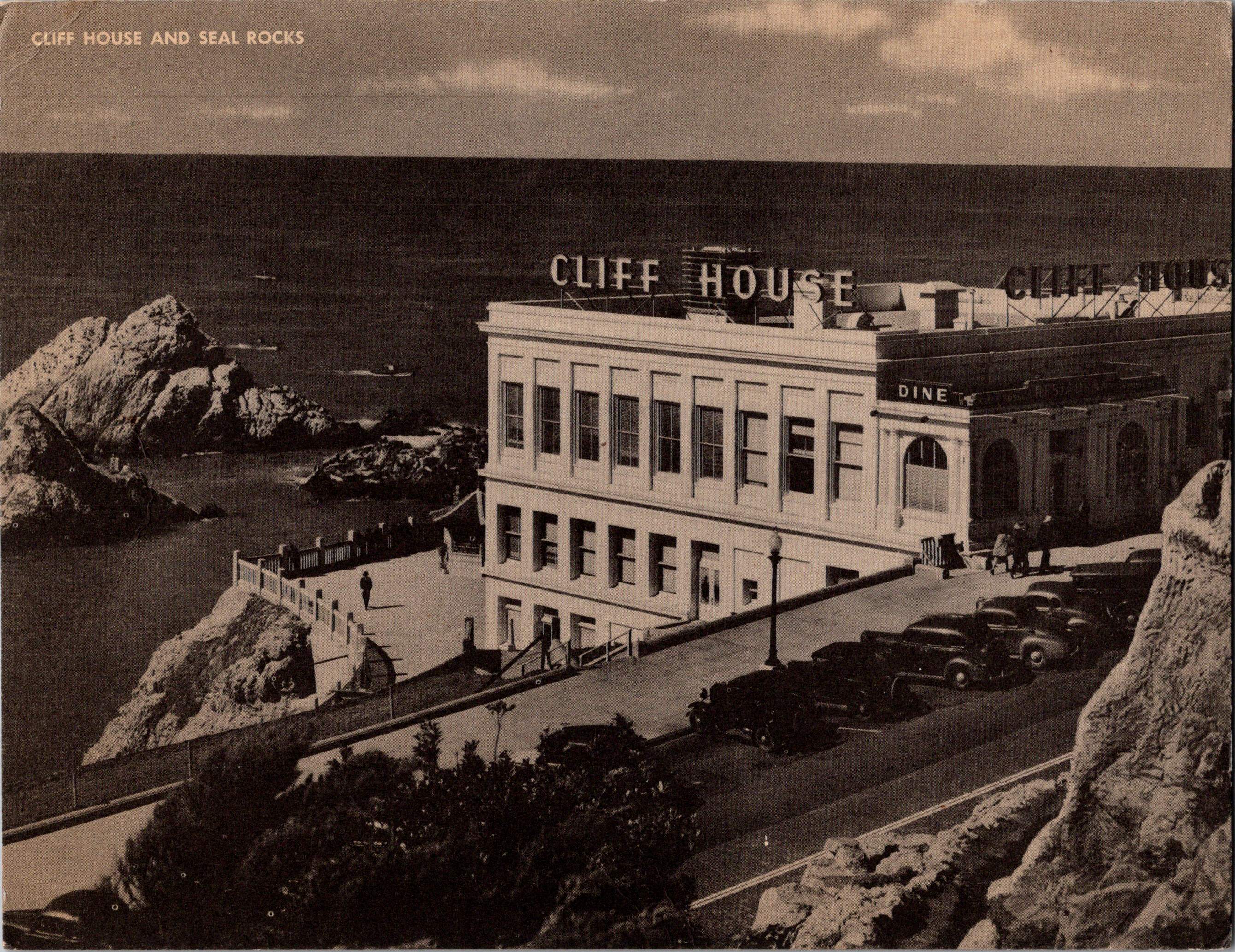

Cliff House: A San Francisco Institution

The postcard depicting Cliff House offers a view of one of San Francisco’s most enduring landmarks. Perched on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Cliff House has been a San Francisco institution since the 19th century, though the building in this image is not the original structure.

Moulin’s photograph captures the Cliff House in its mid-20th century incarnation. This version of the building, with its clean, modernist lines, was a stark contrast to the ornate Victorian structure that had previously occupied the site. The new Cliff House, opened in 1909 and remodeled in the 1930s, reflected changing architectural tastes and the city’s forward-looking attitude.

In the foreground of the image, we can see the rocky shoreline and the famous Seal Rocks. These natural features had long made this area a popular destination for San Franciscans and tourists alike. The juxtaposition of the sleek, modern building against the rugged natural landscape creates a compelling visual contrast.

The photograph also shows several automobiles parked near the Cliff House, indicating its popularity as a destination. In the post-war period, the Cliff House continued to be a beloved spot for dining, socializing, and enjoying spectacular ocean views. Its inclusion in this set of postcards speaks to its significance in the tourist imagination of San Francisco.

Moulin’s composition emphasizes the Cliff House’s dramatic setting. The building seems to rise organically from the rocky cliffs, a man-made extension of the natural landscape. This image likely appealed to tourists as a representation of San Francisco’s unique blend of urban sophistication and natural beauty.

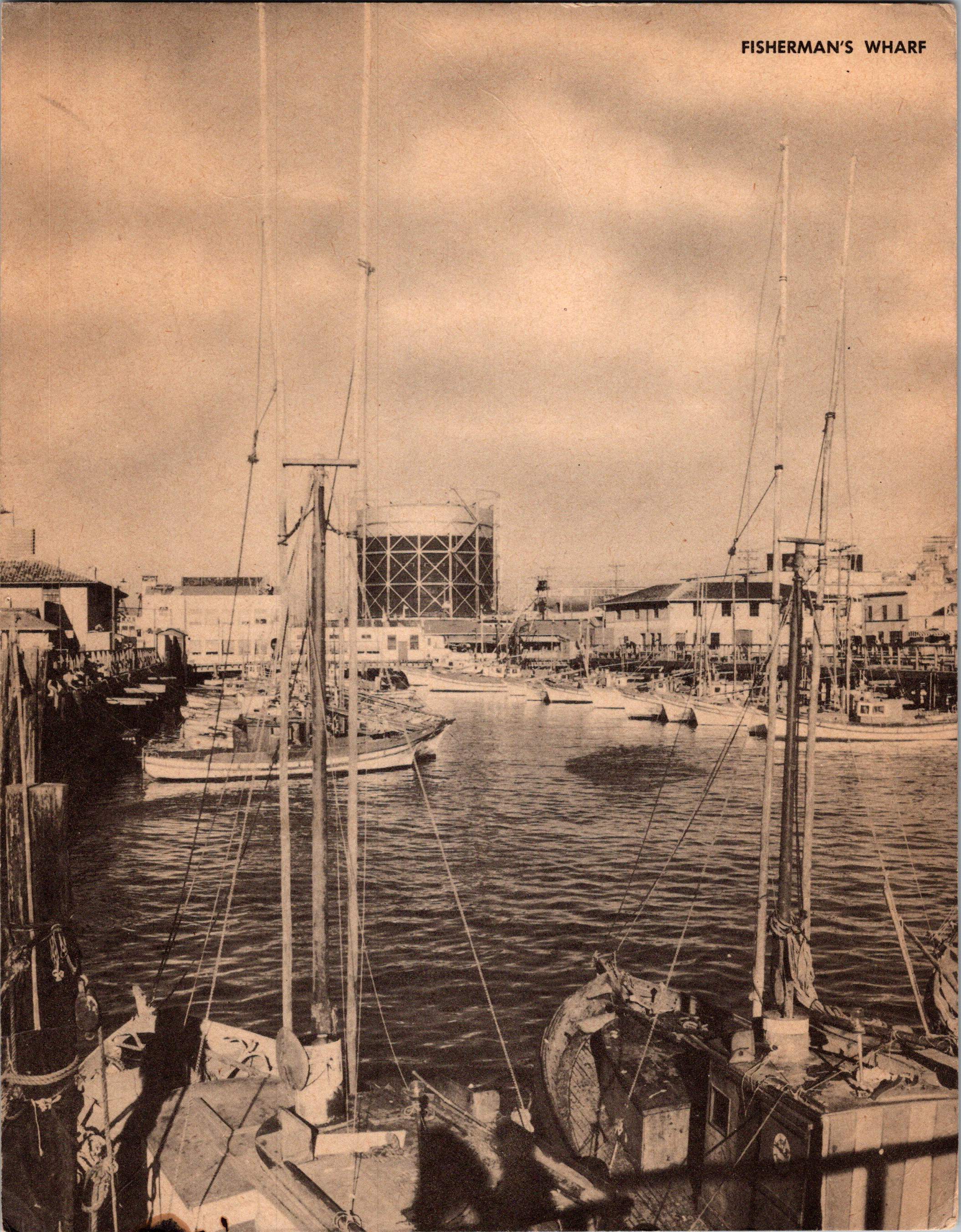

Fisherman’s Wharf: The Heart of Maritime Heritage

The postcard of Fisherman’s Wharf offers a glimpse into one of San Francisco’s most iconic neighborhoods. This image captures the working waterfront that has long been central to the city’s identity and economy.

In Moulin’s photograph, we see a forest of masts belonging to fishing boats docked in the harbor. The image conveys the bustling activity of the wharf, with boats of various sizes crowding the water. In the background, we can make out the buildings of the waterfront, including what appears to be a fish processing plant or warehouse.

This view of Fisherman’s Wharf represents a moment in time when the area was transitioning from a primarily industrial zone to a major tourist attraction. In the post-war years, while commercial fishing remained an important industry, the wharf was increasingly drawing visitors eager to experience its maritime atmosphere, fresh seafood, and picturesque views.

The image on the postcard is complemented by text on the reverse side, which provides context for the scene. It describes Fisherman’s Wharf as a “famous tourist center” where visitors can enjoy fresh seafood like crabs, bass, salmon, and shrimp. This description highlights how the working waterfront was being marketed as a unique cultural experience for tourists.

Interestingly, the text on the postcard also mentions that this view shows “a few of the many small fishing craft engaged in commercial fishing activities along the Pacific Coast.” This statement underscores the dual nature of Fisherman’s Wharf at this time – both a working port and a tourist destination.

The postcard credits the Redwood Empire Association for the photograph, indicating a collaborative effort between different organizations to promote San Francisco’s attractions. The Redwood Empire Association, founded in 1925, was primarily focused on promoting tourism in the coastal regions of Northern California. Their involvement in producing this postcard demonstrates the growing importance of tourism to San Francisco’s economy in the post-war period.

A Changing San Francisco

Taken together, these postcards offer a multifaceted view of San Francisco in the mid-20th century. From the cultural enclave of Chinatown to the engineering marvel of the Bay Bridge, from the storied Cliff House to the working waterfront of Fisherman’s Wharf, each image captures a different aspect of the city’s identity.

These postcards represent more than just tourist souvenirs; they are windows into a particular moment in San Francisco’s history. They show a city in transition, balancing its historical roots with post-war modernization and growth. The images capture the optimism and energy of the era, when San Francisco was cementing its place as a major American city and an international tourist destination.

The Art of Postcard Photography

Gabriel Moulin’s approach to photographing San Francisco for these postcards reveals much about the art of postcard photography in the mid-20th century. Each image is carefully composed to showcase the subject in its best light while also conveying a sense of place and atmosphere.

In the Chinatown image, Moulin (or his sons) made the deliberate choice to include people in the scene, unlike the other, more architecturally focused postcards. This human element brings the street to life, offering viewers a sense of the neighborhood’s vibrant culture and daily activities. The inclusion of both traditionally dressed individuals and those in more Western attire subtly communicates the neighborhood’s cultural complexity.

The Bay Bridge photograph demonstrates Moulin’s skill in capturing large-scale structures. The composition emphasizes the bridge’s sweeping lines and monumental scale, with the city skyline providing context and contrast. The small boat in the foreground adds a sense of scale and a touch of maritime romance.

The Cliff House image showcases Moulin’s ability to capture the interplay between natural and man-made environments. The framing of the building, perched on the edge of the continent, emphasizes its unique location and architectural drama.

In the Fisherman’s Wharf postcard, the photographer chose a viewpoint that emphasizes the dense forest of masts, creating a strong visual impression of a busy, thriving port. This image captures both the industrial nature of the area and its picturesque qualities that appealed to tourists.

Across all these images, we can see a consistent aesthetic that defines the postcard genre of this era. The compositions are clean and direct, presenting each subject clearly and attractively. The use of sepia toning adds a sense of nostalgia and timelessness, even to relatively modern scenes. This technique helped to present San Francisco as a city with a rich history, even as it embraced post-war modernity.

The production and distribution of these postcards represent a fascinating aspect of mid-20th century tourism and printing industries. The collaboration between Moulin Studios and Smith’s News Company exemplifies the specialized roles that developed in the postcard business.

Moulin Studios, with its vast archive of high-quality images and reputation for excellence in photography, was the ideal source for postcard imagery. The studio’s deep connection to San Francisco meant that it could provide not just beautiful pictures, but images that truly captured the essence of the city.

Smith’s News Company, as the publisher and distributor, played a crucial role in bringing these images to the public. Located on Ninth Street in San Francisco, Smith’s would have handled the technical aspects of postcard production, including printing, cutting, and distributing the cards to various retail outlets throughout the city.

The choice to produce these as jumbo postcards, larger than the standard size, was likely a marketing decision. The larger format allowed for more detail in the images and made the postcards stand out among other souvenir options. This size also aligned with the general trend towards “bigger and better” that characterized much of American consumer culture in the post-war years.

The postcards were more than just souvenirs; they were also a form of advertising for San Francisco. Tourists who bought and sent these postcards were essentially becoming ambassadors for the city, sharing enticing images of San Francisco with friends and family across the country and around the world.